Fungi are a unique kingdom of organisms that differ significantly from plants and animals in their reproductive strategies. Unlike plants, which produce fruits and seeds, fungi do not have these structures. Instead, fungi reproduce through the release of spores, which are microscopic, single-celled or multicellular structures capable of developing into new fungal individuals under favorable conditions. These spores are produced in various parts of the fungus, such as gills, pores, or other specialized structures, and are dispersed through air, water, or animals to colonize new environments. This method of reproduction allows fungi to thrive in diverse habitats and play crucial roles in ecosystems, such as decomposing organic matter and forming symbiotic relationships with other organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Fungi reproduce primarily through spores, not seeds. |

| Presence of Fruit | Fungi do not produce fruit like plants; some form fruiting bodies (e.g., mushrooms) that release spores. |

| Spores | Spores are the primary reproductive units of fungi, produced in vast quantities. |

| Seed Production | Fungi do not produce seeds; seeds are a characteristic of plants. |

| Fruiting Bodies | Structures like mushrooms, truffles, and molds are fruiting bodies that release spores. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are dispersed through air, water, or animals; seeds require external agents for dispersal. |

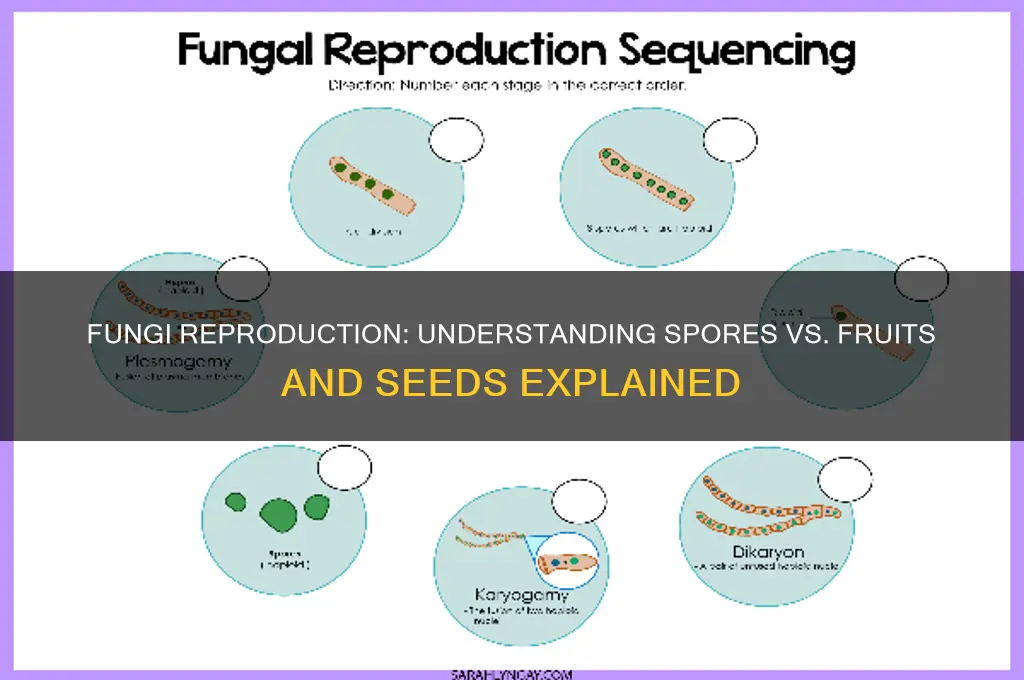

| Life Cycle | Fungi have a life cycle involving spore germination, mycelium growth, and spore production. |

| Nutrient Acquisition | Fungi absorb nutrients directly from their environment, unlike plants that use seeds for nutrient storage. |

| Classification | Fungi belong to the kingdom Fungi, distinct from plants (kingdom Plantae). |

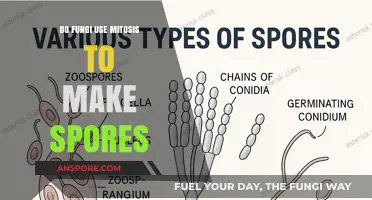

| Examples of Spores | Conidia, basidiospores, asci, and zygospores are common types of fungal spores. |

Explore related products

$147.96

What You'll Learn

- Fungal Reproduction Methods: Fungi reproduce via spores, not seeds, unlike plants

- Spores vs. Seeds: Spores are microscopic; seeds are larger, embryo-containing structures

- Fungal Fruit Bodies: Mushrooms are fungi’s fruiting bodies, producing and dispersing spores

- Sporulation Process: Fungi release spores through gills, pores, or other structures for dispersal

- Seedless Kingdom: Fungi belong to their own kingdom, distinct from seed-bearing plants

Fungal Reproduction Methods: Fungi reproduce via spores, not seeds, unlike plants

Fungi, unlike plants, do not produce seeds or fruits. Instead, they rely on spores as their primary means of reproduction. This fundamental difference highlights the unique evolutionary path of fungi, which diverged from plants over a billion years ago. Spores are microscopic, lightweight structures that allow fungi to disperse widely, colonizing diverse environments from forest floors to human lungs. Understanding this reproductive strategy is crucial for fields like mycology, agriculture, and medicine, as it explains how fungi thrive and spread.

Analyzing the spore production process reveals its efficiency. Fungi generate spores through both sexual and asexual methods, depending on the species and environmental conditions. For instance, mushrooms release billions of spores from their gills, while molds like *Aspergillus* produce spores in chains called conidia. This adaptability ensures survival in varying habitats, from nutrient-rich soil to decaying matter. Unlike seeds, which require specific conditions to germinate, spores can remain dormant for years, waiting for optimal conditions to sprout. This resilience makes fungi formidable colonizers, often outcompeting other organisms in challenging environments.

From a practical standpoint, knowing how fungi reproduce via spores is essential for controlling their growth. In agriculture, fungal spores can cause devastating crop diseases, such as wheat rust or potato blight. Farmers use fungicides and crop rotation to mitigate spore dispersal, but timing is critical. For example, applying fungicides during spore release can reduce infection rates by up to 90%. Similarly, in indoor environments, controlling humidity and ventilation can prevent mold spores from germinating, safeguarding human health and structural integrity.

Comparing fungal spores to plant seeds underscores their distinct advantages and challenges. While seeds are resource-intensive to produce, spores are energy-efficient, allowing fungi to allocate more resources to growth and survival. However, spores’ small size and airborne nature make them difficult to contain, contributing to allergies and infections in humans. For instance, inhaling *Aspergillus* spores can lead to aspergillosis, a serious lung condition, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. This comparison highlights the trade-offs in fungal reproduction and its implications for both ecosystems and human health.

In conclusion, fungi’s reliance on spores for reproduction sets them apart from plants and underpins their ecological success. By producing vast quantities of lightweight, resilient spores, fungi ensure their survival across diverse and often harsh conditions. Whether in the wild or in human-managed environments, understanding spore-based reproduction is key to managing fungal growth, from protecting crops to preventing disease. This knowledge not only deepens our appreciation of fungal biology but also equips us with practical tools to coexist with these ubiquitous organisms.

Shroomish's Spore Move: When and How to Unlock It

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Seeds: Spores are microscopic; seeds are larger, embryo-containing structures

Fungi do not produce seeds; instead, they rely on spores for reproduction. This fundamental difference between spores and seeds is crucial for understanding fungal biology. Spores are microscopic, single-celled structures that can be dispersed through air, water, or animals, allowing fungi to colonize new environments rapidly. Seeds, in contrast, are larger, multicellular structures found in plants, containing an embryo, nutrient storage, and protective layers. This distinction highlights the unique reproductive strategies of fungi and plants, with spores enabling fungi to thrive in diverse habitats without the need for complex seed structures.

Consider the scale: a single fungal spore is typically 1–100 micrometers in size, invisible to the naked eye, while a seed, like that of an apple or sunflower, can be several millimeters to centimeters long. This size disparity reflects their functions. Spores are designed for dispersal and survival in harsh conditions, often remaining dormant until optimal growth conditions arise. Seeds, however, are equipped to nurture a developing plant embryo, providing it with the resources needed to grow into a mature organism. For gardeners or mycologists, understanding this size difference is essential for identifying whether they are dealing with fungal spores or plant seeds in soil or on surfaces.

From a practical standpoint, the microscopic nature of spores makes them challenging to manage but also highly efficient for fungal survival. For instance, a single mushroom can release billions of spores, ensuring at least some find suitable environments to germinate. In contrast, seeds require more energy to produce and are less numerous, but their larger size and protective coatings increase the chances of successful germination. Home gardeners can use this knowledge to their advantage: sterilizing soil at 180°F (82°C) for 30 minutes can kill fungal spores, while seeds often require specific conditions like moisture and warmth to sprout.

The comparison between spores and seeds also underscores their ecological roles. Spores contribute to fungi’s role as decomposers, breaking down organic matter and recycling nutrients in ecosystems. Seeds, on the other hand, drive plant reproduction and ecosystem succession, ensuring the continuity of plant species. For educators or enthusiasts, illustrating this difference with examples—such as comparing a dandelion seed to a mold spore under a microscope—can make abstract concepts tangible. Both structures, though distinct, are marvels of evolution, each tailored to the reproductive needs of their respective organisms.

In summary, while spores and seeds serve similar purposes in reproduction, their differences in size, structure, and function reflect the unique adaptations of fungi and plants. Spores’ microscopic size and resilience make them ideal for fungal dispersal, while seeds’ larger, embryo-containing design supports plant growth. Recognizing these distinctions not only deepens our understanding of biology but also informs practical applications, from gardening to ecological conservation. Whether you’re a scientist, hobbyist, or curious observer, appreciating the nuances of spores and seeds enriches our perspective on the natural world.

Optimal Timing for Planting Morel Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Fungal Fruit Bodies: Mushrooms are fungi’s fruiting bodies, producing and dispersing spores

Fungi, unlike plants, do not produce fruits or seeds. Instead, they rely on spores for reproduction, and mushrooms are the most recognizable structures through which many fungi disperse these spores. These mushroom structures are known as fruiting bodies, a term that can be misleading due to its similarity to plant fruits. However, fungal fruiting bodies serve a distinct purpose: they are the spore-producing organs of fungi, designed to release spores into the environment. This process is essential for the survival and propagation of fungal species, as spores can travel through air, water, or animal carriers to colonize new habitats.

Consider the lifecycle of a mushroom. Beneath the soil or decaying matter lies the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus that absorbs nutrients. When conditions are favorable—often involving specific temperature, humidity, and nutrient levels—the mycelium allocates energy to form a fruiting body. This mushroom emerges above ground, its cap and gills or pores serving as the spore-producing factory. For example, the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*) develops gills underneath its cap, where spores are generated and eventually released in vast quantities. This dispersal mechanism ensures genetic diversity and the potential for widespread colonization.

From a practical standpoint, understanding fungal fruiting bodies is crucial for foragers, gardeners, and ecologists. Foragers must identify mushrooms accurately, as some fruiting bodies are edible (like chanterelles or shiitakes) while others are toxic (such as the death cap, *Amanita phalloides*). Gardeners can encourage beneficial fungi by maintaining healthy soil conditions that promote mycelial growth and fruiting. Ecologists study fruiting bodies to assess biodiversity and ecosystem health, as fungi play vital roles in nutrient cycling and decomposition. For instance, the presence of certain mushroom species in a forest indicates a thriving fungal network beneath the surface.

A comparative analysis highlights the efficiency of fungal spore dispersal versus plant seed dispersal. While seeds are often encased in protective fruits and rely on animals or wind for transport, fungal spores are microscopic and produced in astronomical numbers. A single mushroom can release billions of spores, vastly increasing the odds of successful colonization. This strategy compensates for the lack of mobility in fungi, ensuring their survival across diverse environments, from tropical rainforests to Arctic tundra. In contrast, plants invest energy in larger, more complex reproductive structures, reflecting their different evolutionary paths.

In conclusion, fungal fruiting bodies like mushrooms are not fruits in the botanical sense but specialized structures for spore production and dispersal. Their role in the fungal lifecycle underscores the adaptability and resilience of fungi as a kingdom. By studying these fruiting bodies, we gain insights into fungal biology, ecological interactions, and practical applications, from food production to environmental conservation. Whether you’re a forager, scientist, or nature enthusiast, appreciating the function of mushrooms as spore factories deepens our understanding of the natural world.

Mastering Mushroom Spore Collection: Techniques for Successful Harvesting

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.25 $11.99

Sporulation Process: Fungi release spores through gills, pores, or other structures for dispersal

Fungi, unlike plants, do not produce fruits or seeds. Instead, they rely on spores for reproduction and dispersal. The sporulation process is a fascinating mechanism where fungi release these microscopic units through specialized structures such as gills, pores, or other unique formations. This method ensures that fungi can propagate efficiently across diverse environments, from forest floors to decaying matter.

Consider the mushroom, a familiar fungus, which typically releases spores from its gills located beneath the cap. When mature, these gills dry out, allowing air currents to carry the spores away. For instance, a single Agaricus bisporus mushroom can release up to 16 billion spores in just one day. This staggering number highlights the efficiency of sporulation as a dispersal strategy. Similarly, bracket fungi release spores through pores on their undersides, while puffballs disperse spores explosively when disturbed. Each structure is adapted to maximize spore release in its specific habitat.

The sporulation process is not random but highly regulated. Fungi respond to environmental cues like humidity, light, and nutrient availability to initiate spore production. For example, some species require a specific temperature range (e.g., 20–25°C) and high humidity (above 90%) to sporulate effectively. Gardeners and mycologists can replicate these conditions to cultivate fungi, ensuring optimal spore release. However, improper conditions, such as excessive moisture or inadequate airflow, can lead to mold growth instead of sporulation, underscoring the need for precision.

Comparatively, while plants rely on seeds encased in protective fruits for dispersal, fungal spores are lightweight and numerous, allowing them to travel vast distances via wind, water, or animals. This difference reflects the distinct evolutionary strategies of fungi and plants. Spores’ resilience enables them to survive harsh conditions, such as extreme temperatures or desiccation, until they land in a suitable environment for germination. This adaptability is why fungi thrive in ecosystems where plants cannot.

In practical terms, understanding sporulation can aid in both fungal cultivation and control. For instance, mushroom growers manipulate humidity and temperature to encourage spore release and subsequent fruiting. Conversely, homeowners combating mold can reduce indoor humidity below 60% and improve ventilation to inhibit sporulation. By recognizing the structures and conditions that facilitate spore dispersal, one can either harness or hinder this process effectively. The sporulation process, though invisible to the naked eye, is a cornerstone of fungal survival and a key to managing their presence in various settings.

Mold Spores and Pain: Uncovering the Hidden Health Risks

You may want to see also

Seedless Kingdom: Fungi belong to their own kingdom, distinct from seed-bearing plants

Fungi, often mistaken for plants, occupy their own distinct kingdom—a realm devoid of seeds and fruits. Unlike seed-bearing plants, which rely on seeds for reproduction, fungi reproduce through spores. These microscopic structures are dispersed through air, water, or animals, allowing fungi to colonize diverse environments, from forest floors to human lungs. This fundamental difference in reproductive strategy underscores the evolutionary divergence between fungi and plants, highlighting why fungi are classified in the Seedless Kingdom.

Consider the mushroom, a familiar fungal organism. While its cap and stem might resemble a plant’s fruit, it is not a fruit in the botanical sense. Instead, the underside of the cap bears gills or pores where spores are produced. A single mushroom can release millions of spores, each capable of growing into a new fungus under the right conditions. This spore-based reproduction is efficient and adaptable, enabling fungi to thrive in niches where plants cannot survive, such as decaying wood or nutrient-poor soils.

To understand the significance of this distinction, compare fungi to seed-bearing plants. Plants invest energy in producing seeds, which contain stored nutrients and protective coatings to ensure survival during dispersal. Fungi, on the other hand, produce lightweight spores that require minimal energy to create but are highly dependent on environmental conditions for germination. This trade-off—energy efficiency versus survival assurance—reflects the unique ecological roles of fungi and plants. For gardeners or hobbyists, recognizing this difference is crucial: fungicides and herbicides target distinct biological processes, and misidentification can lead to ineffective treatment.

Practically, this knowledge informs how we interact with fungi. For instance, if you’re cultivating mushrooms at home, maintaining humidity and temperature is critical for spore germination. A simple setup—a sterile substrate like straw or sawdust, kept at 70–75°F (21–24°C) with 80–90% humidity—can encourage spore growth. Conversely, if you’re managing fungal overgrowth in a garden, understanding that spores are airborne helps in implementing preventive measures, such as improving air circulation or using fungistatic agents.

In essence, the Seedless Kingdom of fungi is defined by its spore-driven existence, a strategy that contrasts sharply with the seed-based reproduction of plants. This distinction is not merely academic; it has practical implications for agriculture, medicine, and ecology. By appreciating the unique biology of fungi, we can better harness their benefits—from decomposing organic matter to producing antibiotics—while mitigating their drawbacks, such as crop diseases or indoor mold. Fungi’s seedless nature is both their limitation and their strength, a reminder of the diversity of life’s strategies.

Mold Spores in Rain: Unseen Passengers and Their Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungi do not produce fruit in the same way plants do. However, some fungi, like mushrooms, form fruiting bodies that release spores, which are analogous to the reproductive structures of plants but serve a different function.

Fungi do not have seeds. Instead, they reproduce through spores, which are microscopic, single-celled structures that can develop into new fungal organisms under suitable conditions.

Spores are reproductive units produced by fungi (and some other organisms) that are typically single-celled and can disperse through air, water, or other means. Unlike seeds, spores do not contain an embryo or stored food and are much smaller and simpler in structure.

Fungi disperse spores through various methods, such as wind, water, or animals, depending on the species. Spores are lightweight and numerous, allowing for widespread dispersal. In contrast, plant seeds are often dispersed by animals, wind, or water but are larger and contain resources to support early growth.