The question of whether fungal spores germinate before producing a fruiting body is a fascinating aspect of mycology. Fungal spores, which are the reproductive units of fungi, typically germinate under favorable conditions such as adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability. During germination, a spore develops into a hypha, which is a filamentous structure that forms the vegetative part of the fungus. This hyphal network, known as the mycelium, grows and expands to colonize its substrate. Only after the mycelium has sufficiently developed and resources are abundant does the fungus allocate energy to produce a fruiting body, such as a mushroom or mold. The fruiting body serves as the reproductive structure that releases new spores into the environment, completing the life cycle. Thus, germination precedes the formation of a fruiting body, highlighting the sequential and resource-dependent nature of fungal development.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Germination Process | Fungal spores typically germinate directly into hyphae (filamentous structures) without first producing a fruiting body. |

| Fruiting Body Formation | Fruiting bodies (e.g., mushrooms, molds) are produced later in the fungal life cycle, often as a means of spore dispersal. |

| Role of Spores | Spores are primarily dispersal units and can remain dormant until favorable conditions trigger germination. |

| Environmental Triggers | Germination requires specific environmental conditions such as moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability, not the presence of a fruiting body. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Fruiting bodies are part of the sexual or asexual reproductive phase, while spore germination is part of the vegetative growth phase. |

| Hyphal Growth | After germination, spores develop into hyphae, which form the mycelium (the vegetative part of the fungus). |

| Spore Types | Different spore types (e.g., ascospores, basidiospores, conidia) germinate similarly, regardless of fruiting body presence. |

| Exceptions | Some fungi (e.g., certain yeasts) may have unique life cycles, but the general rule is that spores germinate before fruiting bodies are produced. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Fungal spore germination process

Fungal spores are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions until they encounter an environment conducive to growth. However, germination—the process by which a spore awakens from dormancy and begins to grow—does not inherently require the prior formation of a fruiting body. This misconception stems from the visible association of fruiting bodies (like mushrooms) with spore dispersal, but germination is a distinct, earlier stage in the fungal life cycle. Understanding this process is crucial for fields like agriculture, medicine, and ecology, where fungal growth can be either beneficial or detrimental.

The germination of fungal spores is a complex, multi-step process influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and nutrient availability. When conditions are optimal, a spore absorbs water, triggering metabolic activity and the breakdown of stored reserves. This is followed by the emergence of a germ tube, a filamentous structure that marks the beginning of vegetative growth. For example, *Aspergillus* spores germinate within hours under favorable conditions, rapidly colonizing substrates like decaying organic matter. In contrast, spores of some basidiomycetes, like those of mushrooms, may require specific chemical signals from their environment to initiate germination, highlighting the diversity in fungal responses.

From a practical standpoint, controlling spore germination is essential in preventing fungal infections in crops and humans. For instance, maintaining low humidity levels can inhibit the germination of *Botrytis cinerea*, a pathogen that causes gray mold in plants. Similarly, antifungal agents often target the germination process by disrupting cell wall synthesis or membrane integrity. In laboratory settings, researchers induce spore germination by providing a nutrient-rich medium, such as potato dextrose agar, and incubating at temperatures between 25°C and 30°C, ideal for many fungal species.

Comparatively, the role of fruiting bodies in spore production is secondary to germination. Fruiting bodies develop only after a fungus has established a network of hyphae (the vegetative part of the fungus) and requires energy to form. This distinction is critical: germination is about survival and initial growth, while fruiting bodies are reproductive structures for spore dispersal. For example, the mycelium of a mushroom may grow underground for years before producing a fruiting body, yet its spores remain viable and capable of germinating independently.

In conclusion, the fungal spore germination process is a self-contained mechanism that does not depend on the prior existence of a fruiting body. By focusing on the environmental and biochemical triggers of germination, we can better manage fungal growth in various contexts. Whether preventing crop diseases or cultivating beneficial fungi, understanding this process empowers us to manipulate fungal behavior effectively.

Are Psilocybin Mushroom Spores Illegal? Understanding the Legal Landscape

You may want to see also

Conditions for spore germination

Fungal spores, the microscopic units of reproduction, require specific conditions to germinate and initiate the growth of a new fungal organism. Unlike seeds, which often need a period of dormancy or a specific trigger to sprout, fungal spores are poised to germinate under the right environmental cues. These cues are not arbitrary; they are finely tuned to ensure that the spore germinates when conditions are optimal for survival and growth. Understanding these conditions is crucial for both controlling fungal growth in unwanted areas and cultivating fungi in agricultural or laboratory settings.

Optimal Environmental Factors

Spore germination hinges on a triad of environmental factors: moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability. Moisture is paramount, as water activates the metabolic processes necessary for germination. Most fungal spores require a water activity (aw) of at least 0.88 to 0.90, though some species, like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, can germinate at lower levels (aw ≥ 0.77). Temperature plays a critical role, with most fungi preferring ranges between 20°C and 30°C (68°F to 86°F). Nutrient availability, particularly carbon and nitrogen sources, is equally essential. For instance, glucose is a common carbon source that accelerates germination in many species. Practical tip: To inhibit fungal growth in stored grains, maintain relative humidity below 65% and temperatures under 20°C.

Surface Interaction and pH

The surface on which a spore lands can significantly influence germination. Spores often require a solid substrate to adhere to, as this provides stability and access to nutrients. The pH of the environment also matters; most fungi thrive in neutral to slightly acidic conditions (pH 5.0–7.0). Deviations from this range can inhibit germination. For example, *Trichoderma* species, commonly used in biocontrol, germinate best at pH 5.5–6.5. Caution: Avoid using highly acidic or alkaline cleaning agents in areas prone to fungal growth, as these may inadvertently create favorable conditions for certain species.

Light and Oxygen Requirements

While not universally required, light can influence spore germination in some fungi. For instance, *Neurospora crassa* germinates more efficiently in the presence of light, particularly blue wavelengths. Oxygen is another critical factor, as most fungi are aerobic and require oxygen for energy metabolism during germination. However, some species, like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, can germinate under anaerobic conditions, though this is less common. Practical tip: In laboratory settings, ensure spore cultures are exposed to ambient light and well-ventilated conditions to promote germination.

Chemical Signals and Stressors

Chemical signals, such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) produced by other fungi or plants, can either stimulate or inhibit spore germination. For example, VOCs from *Trichoderma* species can induce germination in *Fusarium* spores, while others may suppress it. Additionally, stressors like osmotic pressure or salinity can affect germination. High salt concentrations, for instance, inhibit germination in most fungi by disrupting water uptake. Comparative analysis: While some fungi are highly sensitive to these stressors, others, like *Eurotium* species, can germinate in environments with high osmotic pressure, making them resilient in extreme conditions.

Practical Application and Takeaway

Understanding the conditions for spore germination is not just academic—it has practical implications. For gardeners, maintaining proper soil moisture and pH can prevent fungal diseases. In food preservation, controlling humidity and temperature can inhibit mold growth. For researchers, manipulating these conditions allows for the cultivation of specific fungal species. Key takeaway: By targeting moisture, temperature, nutrients, and other factors, one can either promote or suppress spore germination, depending on the desired outcome. This knowledge is a powerful tool in both prevention and cultivation.

Are Shroom Spores Illegal? Exploring the Legal Gray Area

You may want to see also

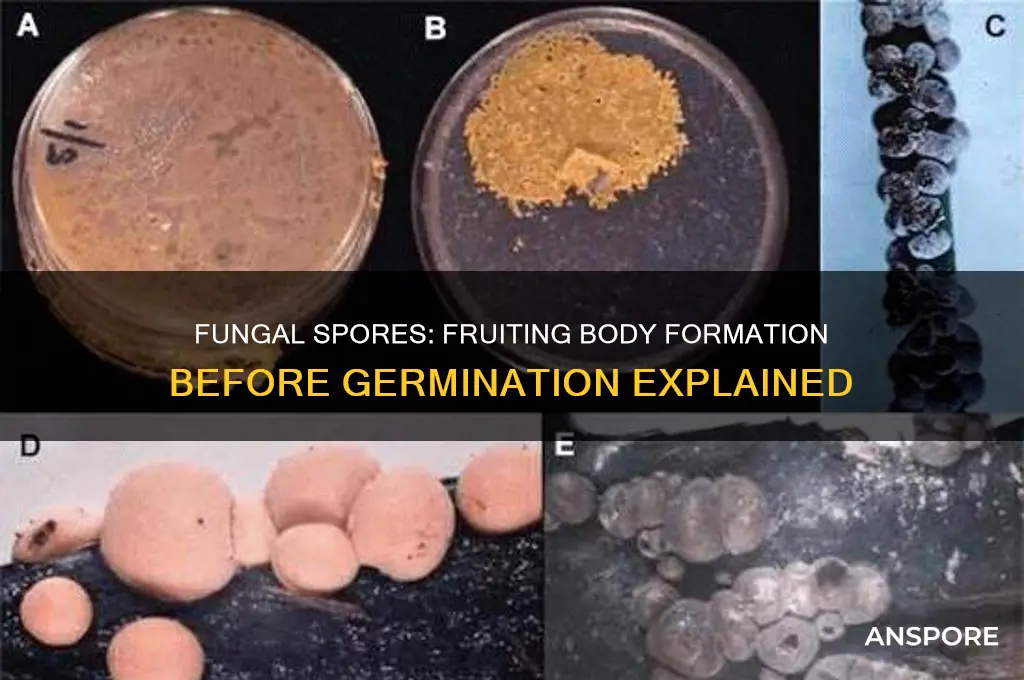

Role of mycelium in fruiting

Fungal spores, when they germinate, do not immediately produce a fruiting body. Instead, they first develop into a network of thread-like structures called mycelium, which plays a crucial role in the life cycle of fungi. This mycelial network is the foundation upon which fruiting bodies, such as mushrooms, eventually form. Understanding the role of mycelium in fruiting requires examining its functions in nutrient acquisition, environmental sensing, and structural support.

From an analytical perspective, mycelium acts as the fungal organism’s primary means of absorbing nutrients from its environment. It secretes enzymes that break down organic matter, such as dead plant material or wood, into simpler compounds that the fungus can absorb. This process is essential for energy acquisition and growth. Without a well-established mycelial network, the fungus lacks the resources necessary to invest in producing fruiting bodies. For example, in cultivated mushrooms like *Agaricus bisporus*, mycelium must first colonize a substrate (e.g., compost) and reach a critical biomass before fruiting is initiated. Practical tip: For mushroom cultivation, ensure the substrate is fully colonized by mycelium before inducing fruiting conditions, such as adjusting humidity and light.

Instructively, mycelium also serves as the fungus’s sensory system, detecting environmental cues that signal optimal conditions for fruiting. Factors like temperature, humidity, and light trigger the mycelium to redirect energy toward fruiting body formation. For instance, many basidiomycetes, such as *Coprinus comatus*, require a period of darkness followed by exposure to light to initiate fruiting. This sensitivity to environmental changes highlights the mycelium’s role as both a survival mechanism and a developmental regulator. Caution: Abrupt changes in environmental conditions can stress the mycelium, delaying or inhibiting fruiting. Gradually adjust parameters like humidity (e.g., from 80% to 95%) to mimic natural transitions.

Comparatively, the structural role of mycelium in fruiting is often overlooked but critical. As fruiting bodies emerge, the mycelium provides physical support and a pathway for nutrient transport to the developing structures. In species like *Armillaria*, the mycelium forms rhizomorphs—dense, root-like structures—that anchor and nourish fruiting bodies. This contrasts with saprotrophic fungi, where mycelium remains diffuse but still channels resources to the fruiting site. Takeaway: The mycelium’s dual role as a nutrient source and structural scaffold underscores its indispensability in the fruiting process.

Descriptively, the transition from mycelium to fruiting body is a marvel of biological efficiency. Once environmental cues are detected, the mycelium aggregates and differentiates into specialized cells that form the fruiting body’s tissues. This process, known as primordium formation, is visible as small knots or bumps on the mycelial mat. Over days to weeks, these primordia develop into mature fruiting bodies, releasing spores to complete the cycle. For hobbyists, observing this transformation in species like *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushrooms) can be both educational and rewarding. Practical tip: Maintain a consistent fruiting environment (e.g., 65–75°F, high humidity) to support primordium development and prevent aborting fruiting bodies.

Persuasively, the role of mycelium in fruiting highlights its importance in both natural ecosystems and applied fields like agriculture and medicine. By understanding and manipulating mycelial behavior, we can enhance mushroom yields, develop mycoremediation strategies, and even produce mycelium-based materials. For example, companies like Ecovative Design use mycelium to create sustainable packaging, leveraging its natural growth patterns. This dual utility—as both a biological process and a resource—makes mycelium a fascinating and valuable subject of study. Conclusion: The mycelium’s multifaceted role in fruiting is not just a biological necessity but a source of inspiration for innovation across disciplines.

Rain's Role in Spreading Fungal Spores: Myth or Reality?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Types of fungal fruiting bodies

Fungal fruiting bodies are the visible structures produced by fungi to release spores, and they come in a dazzling array of forms, each adapted to specific environments and dispersal strategies. Understanding these types not only sheds light on fungal biology but also aids in identification and ecological appreciation.

From the familiar mushrooms to the less conspicuous cup fungi, each type serves a unique purpose in the fungal life cycle.

The Mushroom: A Classic Example

The mushroom, with its cap and stem, is perhaps the most recognizable fruiting body. This structure, technically called a basidiocarp, is characteristic of basidiomycetes, a large group of fungi. The gills or pores underneath the cap are where spores are produced and released. Mushrooms employ a ballistic spore discharge mechanism, where droplets of water hitting the spore surface create enough force to propel them into the air. This adaptation ensures efficient dispersal, even in damp environments.

Agaricus bisporus, the common button mushroom, is a prime example, widely cultivated for its culinary value.

The Truffle: Underground Enigma

Truffles, highly prized in gastronomy, are the subterranean fruiting bodies of certain ascomycete fungi. Their hypogeous (underground) nature necessitates a different dispersal strategy. Truffles rely on animals, particularly mammals with a keen sense of smell, to dig them up and disperse their spores through ingestion and subsequent excretion. This symbiotic relationship highlights the intricate co-evolution between fungi and animals. The pungent aroma of truffles, attributed to compounds like androstenol, acts as a powerful attractant for these spore dispersers.

Tuber melanosporum, the black Périgord truffle, is a coveted delicacy, fetching high prices due to its scarcity and unique flavor profile.

The Puffball: Explosive Dispersal

Puffballs, characterized by their spherical, often white, fruiting bodies, employ a unique spore dispersal mechanism. As the name suggests, mature puffballs release a cloud of spores when disturbed, either by wind, rain, or animal contact. This explosive release ensures widespread dispersal, even in still air conditions. *Calvatia gigantea*, the giant puffball, can grow to impressive sizes, sometimes reaching diameters of 50 cm or more, containing trillions of spores within its fleshy interior.

Beyond the Obvious: Diverse Forms and Functions

The fungal kingdom boasts a remarkable diversity of fruiting body types, each adapted to specific ecological niches. Some, like the bracket fungi (polypores), form shelf-like structures on trees, while others, like the bird's nest fungi, produce tiny, cup-shaped structures that resemble miniature nests filled with "eggs" (spore-containing structures). Understanding this diversity not only deepens our appreciation for the fungal world but also has practical applications in fields like mycoremediation, where specific fungal species are used to degrade pollutants, and in the development of new antibiotics and other bioactive compounds.

Mold Spores: Unveiling Their Role as Reproductive Structures

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for fruiting

Fungal fruiting bodies, such as mushrooms, are the visible structures produced by fungi to release spores. However, spore germination does not require the prior formation of a fruiting body. Instead, spores can germinate directly under suitable conditions, forming mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. The production of fruiting bodies is a separate, environmentally triggered process. Understanding these triggers is crucial for both mycologists and enthusiasts aiming to cultivate fungi or study their ecology.

Environmental cues act as the primary catalysts for fruiting body formation. One of the most critical factors is moisture. Fungi require high humidity levels, typically above 85%, to initiate fruiting. For example, in nature, a sudden rainfall can trigger mushroom emergence within days. In controlled environments, maintaining consistent moisture through misting or humidifiers is essential. However, excessive water can lead to rot, so balance is key. Practical tip: Use a hygrometer to monitor humidity and adjust watering schedules accordingly.

Temperature fluctuations also play a pivotal role. Many fungi require a drop in temperature to transition from mycelial growth to fruiting. For instance, species like *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushrooms) often fruit optimally at temperatures between 15°C and 20°C (59°F–68°F) after a period of warmer growth. This mimics seasonal changes in their natural habitats. In cultivation, a temperature drop of 5–10°C can be artificially induced to stimulate fruiting. Caution: Avoid abrupt temperature changes, as they can stress the mycelium.

Light exposure is another often-overlooked trigger. While fungi do not photosynthesize, many species require light to initiate fruiting. For example, *Coprinus comatus* (shaggy mane) responds to light cycles, fruiting more prolifically under 12–16 hours of indirect light daily. In indoor setups, LED grow lights can be used to simulate natural conditions. Tip: Blue light (450–495 nm) has been shown to enhance fruiting in some species, so consider spectrum-specific lighting for optimal results.

Finally, substrate composition and nutrient depletion are critical. Fungi often fruit when their primary food source is exhausted, forcing them to allocate energy to reproduction. For instance, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) fruit best when the substrate’s nitrogen levels decrease. In cultivation, using spent coffee grounds or straw can provide the right balance of nutrients and structure. Analysis: This strategy mimics natural ecosystems, where fungi decompose organic matter and fruit as a survival mechanism.

By manipulating these environmental triggers—moisture, temperature, light, and substrate conditions—growers can predictably induce fruiting in fungi. While spore germination is independent of fruiting bodies, understanding these cues ensures successful cultivation and deeper insight into fungal biology. Practical takeaway: Experiment with small-scale adjustments to these factors to optimize fruiting yields and timing.

Are Mold Spores Fat Soluble? Unraveling the Science Behind It

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, fungal spores germinate first, and if conditions are favorable, they develop into hyphae, which can later form a fruiting body.

Fungal spores require moisture, suitable temperature, oxygen, and a nutrient source to germinate successfully.

No, spore germination is the initial step; hyphae grow from germinated spores, and under the right conditions, these hyphae develop into a fruiting body.

The time varies by species and environmental conditions, but germination can occur within hours to days, while fruiting body formation may take weeks to months.

No, not all germinated spores develop into fruiting bodies. Factors like nutrient availability, competition, and environmental stress can prevent fruiting body formation.