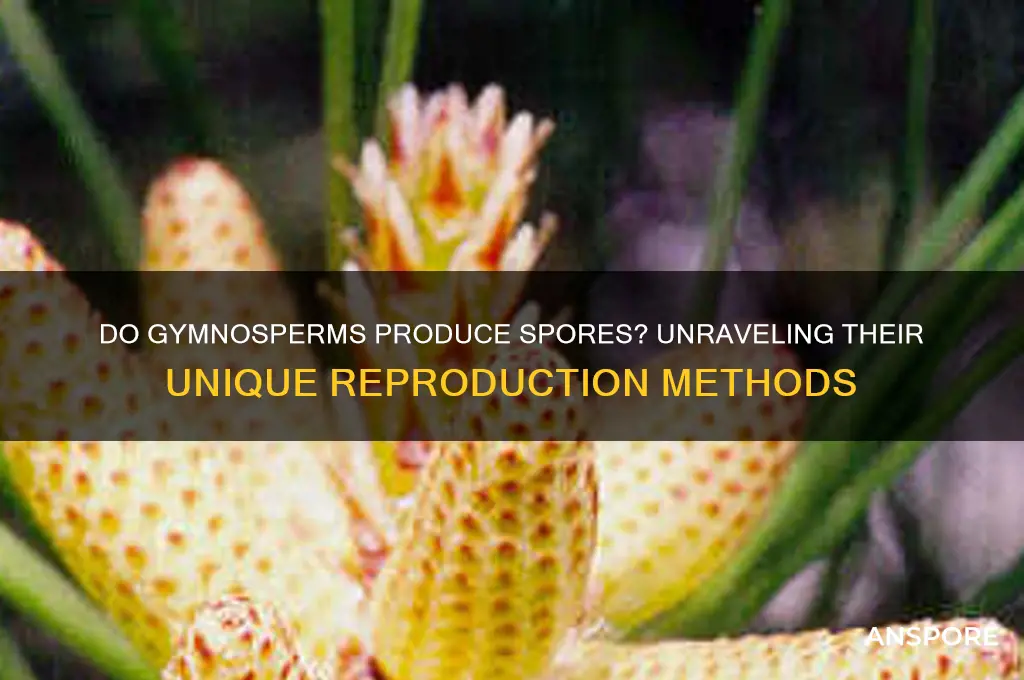

Gymnosperms, a group of seed-producing plants that includes conifers, cycads, and ginkgos, are often distinguished by their method of reproduction. Unlike angiosperms (flowering plants), which produce seeds enclosed within an ovary, gymnosperms have seeds that are typically exposed on the surface of scales or leaves. However, the question of whether gymnosperms produce spores is an important one, as it relates to their life cycle. Gymnosperms do indeed produce spores as part of their alternation of generations, a reproductive strategy shared with other vascular plants. In gymnosperms, the sporophyte (diploid) generation produces two types of spores: microspores, which develop into male gametophytes, and megaspores, which develop into female gametophytes. These spores are crucial for the sexual reproduction of gymnosperms, ultimately leading to the formation of seeds. Thus, while gymnosperms are primarily known for their seeds, their life cycle is intricately tied to the production and development of spores.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do Gymnosperms Produce Spores? | Yes, gymnosperms produce spores as part of their life cycle. |

| Type of Spores Produced | Gymnosperms produce two types of spores: microspores (male) and megaspores (female). |

| Microspores | Develop into pollen grains, which are released and carried by wind to reach the female reproductive structures. |

| Megaspores | Develop within ovules and give rise to the female gametophyte, which produces egg cells. |

| Sporophyte Dominant | Gymnosperms are sporophyte-dominant, meaning the sporophyte (diploid) generation is the most prominent and long-lived phase. |

| Gametophyte Dependency | The gametophyte (haploid) generation is short-lived and depends on the sporophyte for nutrition. |

| Seed Production | Spores in gymnosperms lead to the formation of seeds, which are not enclosed in an ovary (unlike angiosperms). |

| Life Cycle | Alternation of generations: sporophyte produces spores, which grow into gametophytes, and gametophytes produce gametes that form a new sporophyte. |

| Examples of Gymnosperms | Conifers (e.g., pines, spruces), cycads, ginkgo, and gnetophytes. |

| Sporangia Location | Microsporangia (produce microspores) are located in cones or strobili; megasporangia (produce megaspores) are within ovules. |

| Pollination Method | Primarily wind-pollinated, as gymnosperms do not produce flowers or attract pollinators. |

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

- Gymnosperm Reproduction Methods: Gymnosperms reproduce via seeds, not spores, unlike ferns and mosses

- Spores in Plant Life Cycles: Spores are part of alternation of generations, absent in gymnosperms

- Seed Development in Gymnosperms: Seeds form directly from ovules, bypassing spore-dependent stages

- Comparison with Pteridophytes: Pteridophytes use spores; gymnosperms rely on pollination for reproduction

- Gymnosperm Evolution: Gymnosperms evolved seed-based reproduction, replacing spore-dependent methods in their lineage

Gymnosperm Reproduction Methods: Gymnosperms reproduce via seeds, not spores, unlike ferns and mosses

Gymnosperms, a group of seed-producing plants including conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes, stand apart from ferns and mosses in their reproductive strategy. While ferns and mosses rely on spores for reproduction, gymnosperms have evolved to produce seeds, a more advanced and protective method. This distinction is fundamental to understanding the diversity of plant reproductive mechanisms. Seeds, unlike spores, contain an embryo and stored nutrients, encased in a protective coat, which enhances survival and dispersal in various environments.

To appreciate the uniqueness of gymnosperm reproduction, consider the process step-by-step. It begins with pollination, where pollen grains from male cones are transferred to female cones, often by wind. Following fertilization, the ovule develops into a seed, which is then released from the cone. This method contrasts sharply with spore-based reproduction, where plants release microscopic spores that grow into gametophytes, which then produce gametes. Gymnosperms bypass the gametophyte stage entirely, making their reproductive cycle more direct and efficient.

From a practical standpoint, understanding gymnosperm reproduction is crucial for horticulture, forestry, and conservation. For instance, conifer seeds require specific conditions to germinate, such as cold stratification, where seeds are exposed to cold temperatures for several weeks to break dormancy. This technique is widely used in nurseries to ensure successful seedling growth. Additionally, knowing that gymnosperms do not produce spores helps gardeners avoid unnecessary treatments, such as spore-specific fungicides, which are irrelevant to seed-bearing plants.

Comparatively, the seed-based reproduction of gymnosperms offers distinct advantages over spore-based systems. Seeds provide a higher chance of survival due to their protective structures and nutrient reserves, enabling plants to colonize harsher environments. For example, pine seeds can remain dormant in soil for years, germinating only when conditions are favorable. In contrast, spores are more vulnerable to environmental stresses, requiring specific humidity and light conditions to develop into gametophytes. This resilience makes gymnosperms dominant in ecosystems like boreal forests, where ferns and mosses play secondary roles.

In conclusion, gymnosperms’ reliance on seeds rather than spores marks a significant evolutionary advancement in plant reproduction. This method not only ensures greater survival and dispersal but also shapes the ecological niches these plants occupy. By focusing on seed production, gymnosperms have carved out a unique place in the plant kingdom, distinct from spore-dependent plants like ferns and mosses. Whether in scientific research, horticulture, or conservation, recognizing this reproductive difference is key to effectively working with and preserving these vital plant groups.

Ozone's Power: Effectively Eliminating Mold Spores in Your Environment

You may want to see also

Spores in Plant Life Cycles: Spores are part of alternation of generations, absent in gymnosperms

Spores are a fundamental component of the life cycles of many plants, playing a crucial role in the alternation of generations—a reproductive strategy where plants alternate between a diploid sporophyte and a haploid gametophyte phase. This process is particularly prominent in ferns, mosses, and other non-seed plants, where spores serve as the primary means of dispersal and reproduction. However, when examining gymnosperms—a group that includes conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes—it becomes evident that spores are conspicuously absent from their life cycles. Instead, gymnosperms rely on seeds for reproduction, a trait that distinguishes them from spore-producing plants.

To understand why gymnosperms lack spores, consider the evolutionary advantages of seeds. Seeds provide a protective coat and nutrient storage for the developing embryo, enabling plants to survive in diverse environments. In contrast, spores are more vulnerable and require specific conditions to germinate. For instance, fern spores must land in a moist, shaded area to develop into gametophytes, whereas a pine seed can endure harsher conditions before sprouting. This adaptability has allowed gymnosperms to dominate vast ecosystems, from boreal forests to arid landscapes. The absence of spores in gymnosperms is not a deficiency but an adaptation that highlights their evolutionary success.

From a comparative perspective, the life cycles of spore-producing plants and gymnosperms reveal distinct strategies for survival and reproduction. In spore-producing plants, the gametophyte phase is free-living and often dependent on water for fertilization, limiting their distribution to humid environments. Gymnosperms, however, have a reduced gametophyte phase that remains within the seed, eliminating the need for external water during fertilization. This internalization of the reproductive process is a key innovation that explains why gymnosperms thrive in drier climates where spore-dependent plants cannot. The trade-off is clear: spores enable rapid colonization in favorable conditions, while seeds ensure long-term survival in challenging environments.

For gardeners or botanists interested in cultivating gymnosperms, understanding their seed-based life cycle is essential. Unlike spore-producing plants, which often require controlled humidity and light conditions to propagate, gymnosperms can be grown from seeds with minimal intervention. For example, pine seeds can be sown directly into well-draining soil and exposed to natural weather conditions, mimicking their wild dispersal. However, patience is key, as gymnosperms typically have longer germination and growth periods compared to spore-producing plants. This approach not only simplifies cultivation but also underscores the resilience inherent in gymnosperm reproduction.

In conclusion, the absence of spores in gymnosperms is a defining feature that reflects their evolutionary trajectory toward seed-based reproduction. While spores remain vital for the life cycles of many plants, gymnosperms have evolved a more robust strategy that prioritizes protection and adaptability. By studying these differences, we gain insights into the diverse mechanisms plants employ to thrive in their environments. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or simply curious about plant biology, recognizing the role—or absence—of spores in gymnosperms enriches our understanding of the natural world.

Mastering Fern Propagation: A Step-by-Step Guide to Growing Ferns from Spores

You may want to see also

Seed Development in Gymnosperms: Seeds form directly from ovules, bypassing spore-dependent stages

Gymnosperms, such as conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes, produce seeds directly from ovules without relying on spore-dependent stages. Unlike angiosperms, which develop seeds through a complex process involving double fertilization, gymnosperms streamline reproduction by bypassing the intermediate spore phase. This direct development is a defining feature of their life cycle, rooted in their evolutionary history as some of the earliest seed-producing plants. Understanding this process reveals how gymnosperms have adapted to thrive in diverse environments, from dense forests to arid landscapes.

Consider the ovule of a pine tree, a prime example of gymnosperm seed development. After pollination, the male gametophyte delivers sperm directly to the egg within the ovule, initiating fertilization. The resulting zygote develops into an embryo, while the surrounding tissues of the ovule mature into a protective seed coat. Notably, there is no free-living gametophyte stage, as seen in spore-producing plants like ferns. This direct progression from ovule to seed conserves energy and resources, allowing gymnosperms to allocate more to growth and survival in challenging conditions.

From a comparative perspective, this seed development contrasts sharply with that of ferns and mosses, which rely on spores to disperse and regenerate. In these plants, spores germinate into gametophytes, which then produce gametes for fertilization. Gymnosperms, however, eliminate this step by integrating fertilization and seed formation within the ovule. This efficiency is particularly advantageous in habitats where water availability is limited, as gymnosperms do not require a moist environment for spore germination. For gardeners or botanists cultivating gymnosperms, this knowledge underscores the importance of protecting ovules during pollination to ensure successful seed development.

Practically, this unique seed development has implications for conservation and horticulture. For instance, when propagating gymnosperms like redwoods or spruces, focus on creating conditions that support pollination and ovule protection, such as maintaining adequate airflow and minimizing physical damage to cones. Additionally, understanding this direct ovule-to-seed pathway highlights why gymnosperms are often more resilient to environmental stresses than spore-dependent plants. By bypassing the vulnerable spore stage, gymnosperms reduce the risk of desiccation or predation, making them ideal candidates for reforestation projects in arid or degraded areas.

In conclusion, the direct formation of seeds from ovules in gymnosperms is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. This process not only simplifies reproduction but also enhances their adaptability to diverse ecosystems. Whether studying their biology or cultivating them, recognizing this unique developmental pathway provides valuable insights into their success as a plant group. By focusing on protecting ovules and optimizing pollination conditions, enthusiasts can effectively propagate gymnosperms while appreciating their distinct reproductive strategy.

Do Gram-Negative Bacteria Form Spores? Unraveling the Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Comparison with Pteridophytes: Pteridophytes use spores; gymnosperms rely on pollination for reproduction

Gymnosperms and pteridophytes represent distinct evolutionary strategies in plant reproduction, each adapted to their ecological niches. Pteridophytes, such as ferns and horsetails, rely on spores for reproduction. These microscopic, single-celled structures are produced in sporangia and dispersed by wind, allowing pteridophytes to colonize diverse environments. Spores germinate into gametophytes, which are dependent on moisture for fertilization. This method is efficient in damp, shaded habitats but limits their success in drier or more exposed areas. Gymnosperms, in contrast, have evolved a more complex reproductive system centered on pollination. They produce seeds, which contain an embryo and stored nutrients, encased in cones or ovules. This adaptation enables gymnosperms to thrive in a wider range of environments, from arid deserts to dense forests, by reducing reliance on water for reproduction.

The reproductive mechanisms of these groups highlight their evolutionary divergence. Pteridophytes’ spore-based reproduction is a primitive trait shared with earlier plant lineages, reflecting their adaptation to moist, stable ecosystems. Gymnosperms, however, represent a significant advancement with the development of seeds. Seeds provide protection and nourishment to the embryo, increasing survival rates in variable conditions. Pollination, often facilitated by wind or insects, ensures genetic diversity without the need for water as a medium. This shift from spores to seeds marks a critical juncture in plant evolution, enabling gymnosperms to dominate terrestrial landscapes for millions of years.

Practical observations underscore these differences. For instance, in a classroom or garden setting, one can easily collect fern spores from the undersides of fronds and observe their growth in a damp environment. Gymnosperms, like pines or cycads, require pollination, which can be simulated by transferring pollen from male cones to female ovules. While pteridophytes’ spore-to-gametophyte cycle is rapid and visible within weeks, gymnosperms’ seed development takes months or years, reflecting their investment in long-term survival. These experiments illustrate the contrasting reproductive strategies and their ecological implications.

From an ecological perspective, the spore-dependent nature of pteridophytes confines them to specific habitats, such as tropical rainforests or wetlands, where moisture is abundant. Gymnosperms, with their seed-based reproduction, have colonized a broader range of environments, including temperate and arid regions. This adaptability has made gymnosperms foundational species in many ecosystems, providing habitat and resources for diverse organisms. Understanding these differences is crucial for conservation efforts, as pteridophytes are often more vulnerable to habitat disruption, while gymnosperms face threats from deforestation and climate change.

In conclusion, the comparison between pteridophytes and gymnosperms reveals a clear evolutionary progression from spore-based to seed-based reproduction. While pteridophytes excel in moist environments, gymnosperms have leveraged seeds and pollination to dominate diverse landscapes. This distinction not only explains their ecological roles but also offers insights into plant evolution and survival strategies. By studying these differences, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and resilience of plant life on Earth.

Effective Milky Spore Application: A Step-by-Step Guide for Lawn Care

You may want to see also

Gymnosperm Evolution: Gymnosperms evolved seed-based reproduction, replacing spore-dependent methods in their lineage

Gymnosperms, a group of seed-producing plants including conifers, cycads, and ginkgos, represent a pivotal shift in plant reproduction. While their ancestors relied on spores for propagation, gymnosperms evolved a more advanced strategy: seed-based reproduction. This transition marked a significant milestone in plant evolution, offering enhanced protection and dispersal mechanisms for the next generation. Unlike spores, which are microscopic and vulnerable to environmental conditions, seeds encapsulate the embryo with nutrient reserves and protective layers, ensuring higher survival rates in diverse habitats.

To understand this evolutionary leap, consider the reproductive processes of spore-dependent plants like ferns. Spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, but their success hinges on specific environmental conditions—moisture, temperature, and substrate. In contrast, gymnosperms produce seeds that can withstand harsher conditions, such as drought or cold, and remain dormant until favorable conditions arise. This adaptability allowed gymnosperms to colonize a wider range of ecosystems, from arid deserts to dense forests, outcompeting spore-dependent plants in many regions.

The evolution of seeds in gymnosperms also introduced a novel reproductive structure: the ovule. Unlike the exposed spores of ferns, gymnosperm ovules are retained on the parent plant, providing a sheltered environment for fertilization. Pollen grains, another innovation, carry male gametes to the ovule, enabling fertilization without the need for water—a requirement for spore-dependent plants. This shift reduced reliance on aquatic or humid environments, opening new evolutionary pathways for terrestrial dominance.

Practical observations of gymnosperms, such as pine trees, illustrate these adaptations. Pine cones, for instance, house seeds protected by woody scales, which open only when conditions are optimal for dispersal. This mechanism ensures that seeds are released when they have the highest chance of germination. For gardeners or conservationists, understanding this process can inform strategies for seed collection and propagation. For example, collecting pine seeds in late autumn, when cones naturally open, yields viable seeds for reforestation projects.

In conclusion, the evolution of seed-based reproduction in gymnosperms was a transformative event in plant history. By replacing spore-dependent methods, gymnosperms gained resilience, adaptability, and a competitive edge in diverse environments. This evolutionary innovation not only shaped the success of gymnosperms but also laid the groundwork for the later emergence of angiosperms (flowering plants). Studying gymnosperm reproduction offers insights into plant survival strategies and highlights the ingenuity of nature’s solutions to reproductive challenges.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: Crafting Liquid Culture from Spores

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, gymnosperms produce spores as part of their life cycle, specifically during the alternation of generations.

Gymnosperms produce two types of spores: microspores (male) and megaspores (female), which develop into pollen grains and embryos, respectively.

In gymnosperms, microspores develop into pollen grains that fertilize the egg within the ovule, while megaspores give rise to the female gametophyte, which produces the egg.

While gymnosperms do produce spores, they are not classified as spore-bearing plants like ferns because their seeds are not enclosed in an ovary, and they rely on seeds for reproduction rather than dispersing spores directly.