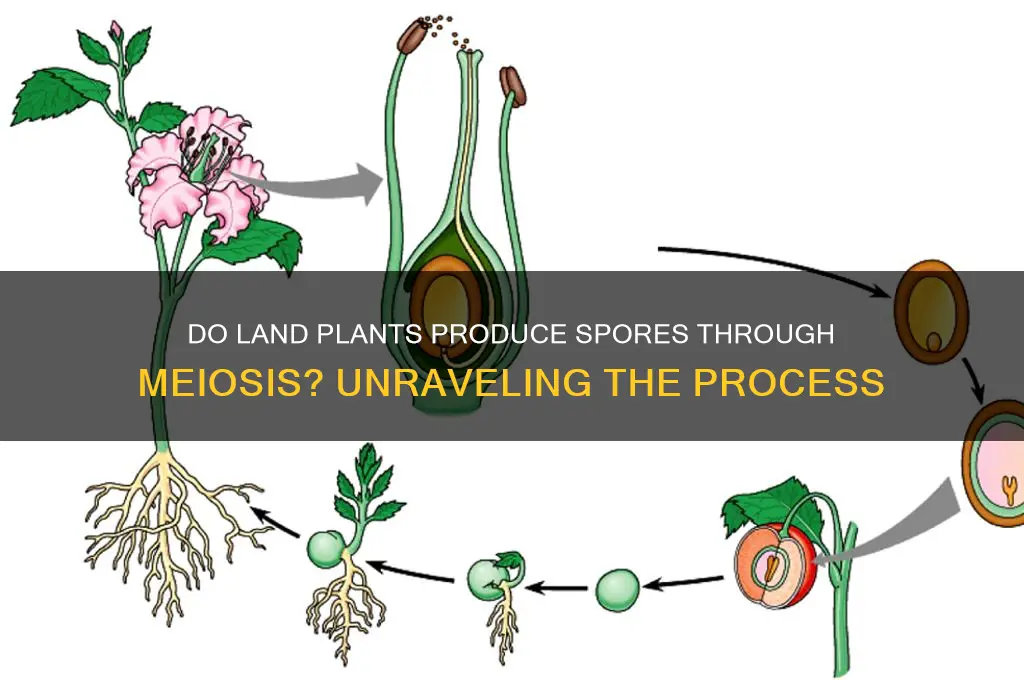

Land plants, including ferns, mosses, and many other species, reproduce through the production of spores, a process that is fundamentally linked to meiosis. Meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, is essential for the formation of spores in these plants. During this process, specialized cells called sporocytes undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores, which can then develop into new individuals under favorable conditions. This method of reproduction allows land plants to disperse their offspring over wide areas and adapt to diverse environments, highlighting the critical role of meiosis in their life cycles.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Involved | Meiosis |

| Type of Reproduction | Asexual (sporulation) |

| Structure Producing Spores | Sporangia |

| Types of Spores Produced | Haploid spores |

| Genetic Variation | High, due to genetic recombination during meiosis |

| Life Cycle Stage | Alternation of generations (sporophyte phase) |

| Examples of Land Plants | Bryophytes, ferns, gymnosperms, angiosperms |

| Function of Spores | Dispersal and survival in adverse conditions |

| Chromosome Number in Spores | Haploid (n) |

| Chromosome Number in Parent Plant | Diploid (2n) |

| Role in Life Cycle | Spores develop into gametophytes, which produce gametes |

| Environmental Adaptation | Spores are lightweight and can be dispersed by wind or water |

| Significance | Ensures genetic diversity and survival of plant species |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporophyte Life Cycle Stage

Land plants, from mosses to trees, exhibit a life cycle that alternates between two distinct generations: the sporophyte and the gametophyte. The sporophyte stage is particularly fascinating because it is during this phase that spores are produced through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half. This process is crucial for genetic diversity and the survival of plant species in varying environments.

Consider the sporophyte as the more prominent and long-lived phase in the life cycles of vascular plants like ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. In these plants, the sporophyte produces spores within specialized structures such as sporangia. For example, in ferns, the sporophyte bears visible sporangia on the undersides of its fronds. Meiosis occurs within these sporangia, generating haploid spores that will later develop into gametophytes. This alternation of generations ensures that each new plant inherits genetic material from two parents, enhancing adaptability.

To understand the sporophyte’s role in spore production, imagine a step-by-step process. First, the mature sporophyte develops sporangia, often in response to environmental cues like seasonal changes. Next, within these structures, cells undergo meiosis, dividing diploid cells into haploid spores. These spores are then released, typically through wind or water, to colonize new areas. For instance, pine trees (gymnosperms) release vast quantities of pollen spores from their cones, while flowering plants (angiosperms) produce spores in flowers that develop into pollen grains. Each spore carries half the genetic information of the parent sporophyte, setting the stage for the next generation.

A critical takeaway is that the sporophyte’s production of spores via meiosis is not just a biological process but a survival strategy. By generating genetically diverse spores, plants increase their chances of thriving in unpredictable conditions. For gardeners or botanists, understanding this stage can inform practices like seed collection or plant breeding. For example, knowing when a plant is in its sporophyte phase can help optimize spore collection for propagation. Similarly, in agriculture, manipulating sporophyte development can enhance crop resilience and yield.

In contrast to vascular plants, non-vascular plants like mosses exhibit a gametophyte-dominant life cycle, where the sporophyte is dependent on the gametophyte for nutrients. However, even in these plants, the sporophyte still produces spores through meiosis, albeit in smaller, less complex structures. This comparison highlights the universality of meiosis in spore production across land plants, despite variations in life cycle dominance. Whether in a towering oak or a humble moss, the sporophyte stage remains a cornerstone of plant reproduction, ensuring continuity and diversity in the plant kingdom.

Do All Microorganisms Form Spores? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Meiosis in Spore Formation

Land plants, from ferns to flowering giants, rely on meiosis as the cornerstone of spore formation. This specialized cell division process slashes chromosome numbers in half, creating haploid spores genetically distinct from the parent plant. Unlike mitosis, which duplicates cells identically for growth, meiosis introduces genetic diversity through crossing over and independent assortment. This diversity is crucial for plant adaptation, enabling species to evolve and thrive in changing environments. Without meiosis, spore formation would lack the variability needed for survival.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a prime example of meiosis in action. Within the fern’s prothallus (the gametophyte stage), meiosis occurs in spore-producing structures called sporangia. Each diploid spore mother cell undergoes two rounds of division, resulting in four haploid spores. These spores, dispersed by wind or water, germinate into new prothalli, perpetuating the cycle. This process ensures genetic reshuffling, allowing ferns to colonize diverse habitats, from shady forests to rocky outcrops.

To understand meiosis in spore formation, visualize it as a precision tool for genetic innovation. During prophase I, homologous chromosomes pair up and exchange segments, a process called crossing over. This genetic recombination is followed by two divisions (meiosis I and II) that reduce the chromosome number from diploid to haploid. The outcome? Spores genetically distinct from the parent plant, ready to disperse and grow into gametophytes. This intricate process underscores the elegance of plant reproduction, blending precision with creativity.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend to horticulture and conservation. For example, understanding meiosis helps breeders develop plant varieties resistant to pests or climate change. By manipulating spore formation, scientists can enhance genetic diversity in crops like wheat or rice, ensuring food security. For gardeners, knowing that spores result from meiosis explains why seedling variations occur, even within the same species. This insight empowers both professionals and enthusiasts to cultivate healthier, more resilient plants.

Can Bulbasaur Learn Stun Spore? Exploring Moveset Possibilities

You may want to see also

Types of Spores Produced

Land plants, from ferns to flowering giants, produce spores through meiosis, a process that ensures genetic diversity. But not all spores are created equal. The plant kingdom showcases a fascinating array of spore types, each adapted to specific environments and reproductive strategies.

Understanding these variations sheds light on the remarkable adaptability of land plants.

Classification by Function: A Spores' Purpose

- Megaspores and Microspores: In seed plants like conifers and angiosperms, a size difference reigns supreme. Megaspores, larger and fewer in number, develop into female gametophytes, while microspores, smaller and more numerous, give rise to male gametophytes. This division of labor ensures efficient pollination and fertilization.

- Sporangiospores: Fungi, though not true plants, also produce spores through meiosis. Sporangiospores, released from sporangia, are a key means of dispersal and survival for many fungal species.

Environmental Adaptations: Spore Survival Strategies

Spores aren't just miniature plant embryos; they're survival capsules. Consider these adaptations:

- Thick Walls: Many spores have robust walls composed of sporopollenin, a highly resistant polymer. This protects them from desiccation, UV radiation, and other environmental stresses during dispersal.

- Dormancy: Some spores enter a state of dormancy, delaying germination until conditions are favorable. This allows them to survive harsh seasons or periods of resource scarcity.

- Dispersal Mechanisms: From the winged spores of ferns to the sticky spores of sundews, plants have evolved ingenious ways to disperse their spores over long distances, increasing their chances of finding suitable habitats.

Beyond the Basics: Specialized Spore Types

The diversity doesn't end there. Some plants produce specialized spore types:

- Carpospores: In red algae, carpospores are formed within specialized structures called carposporophytes. These spores develop into tetrasporophytes, continuing the complex life cycle of these algae.

- Aplanospores: Some algae and fungi produce aplanospores, non-motile spores that are often formed under stressful conditions. These spores can remain dormant until conditions improve.

Practical Applications: Harnessing Spore Power

Understanding spore types has practical implications.

- Agriculture: Knowledge of spore dispersal and germination can inform strategies for crop protection and disease control.

- Biotechnology: Spores' resilience and ability to survive harsh conditions make them attractive candidates for biotechnological applications, such as the production of biofuels and pharmaceuticals.

- Paleontology: Fossilized spores provide valuable insights into past climates and plant evolution.

The world of plant spores is a testament to the ingenuity of nature. From their diverse forms and functions to their remarkable adaptations, spores play a crucial role in the survival and success of land plants. By studying these microscopic marvels, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and beauty of the plant kingdom.

Breloom's Spore Ability: Mirror Herb's Role in Learning the Move

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of Sporangia

Sporangia are the unsung heroes of land plant reproduction, serving as the factories where spores are produced through meiosis. These specialized structures are typically found on the plant’s reproductive organs, such as ferns’ fiddleheads or moss capsules. Inside each sporangium, diploid cells undergo meiosis to create haploid spores, halving the chromosome number and introducing genetic diversity. This process is critical for the plant’s life cycle, enabling adaptation to changing environments and ensuring species survival. Without sporangia, land plants would lack the mechanism to produce spores, disrupting their alternation of generations.

Consider the fern as a case study in sporangial function. On the underside of mature fern fronds, clusters of sporangia called sori develop. Each sporangium releases spores that, when dispersed, can grow into a gametophyte—a small, heart-shaped structure that produces gametes. This gametophyte then facilitates fertilization, leading to the growth of a new sporophyte plant. The sporangia’s role here is not just reproductive but also protective; their location and structure shield the developing spores from desiccation and predation. For gardeners cultivating ferns, ensuring adequate humidity and avoiding physical damage to fronds can optimize sporangial health and spore production.

From an evolutionary perspective, sporangia represent a key innovation that allowed plants to colonize land. Early land plants, like bryophytes, had simpler sporangia, but as plants evolved, these structures became more complex and efficient. For instance, seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms) retain sporangia within cones or flowers, further safeguarding spores and gametophytes. This progression highlights the sporangium’s adaptability, transitioning from exposed structures in ferns to enclosed ones in flowering plants. Understanding this evolution underscores the sporangium’s central role in bridging aquatic and terrestrial reproduction strategies.

Practical applications of sporangial biology extend to agriculture and conservation. In crop plants like maize, sporangia (within the anther) produce pollen spores, essential for fertilization. Farmers can enhance yields by ensuring optimal conditions for sporangial development, such as adequate sunlight and nutrient-rich soil. In conservation, protecting sporangia-bearing plants, like orchids or rare ferns, is vital for preserving biodiversity. For hobbyists propagating plants from spores, harvesting sporangia at the correct maturity stage—typically when they appear dry and brittle—maximizes spore viability. This hands-on approach illustrates the sporangium’s tangible importance in both natural and cultivated ecosystems.

Finally, the sporangium’s role in meiosis is a testament to nature’s efficiency and ingenuity. By compartmentalizing spore production, plants ensure genetic recombination occurs in a controlled, protected environment. This not only safeguards the next generation but also fosters innovation through genetic diversity. For educators, using sporangia as a teaching tool can demystify complex concepts like meiosis and alternation of generations. Observing sporangia under a microscope or dissecting a fern sorus offers students a tangible connection to abstract biological processes. In essence, the sporangium is more than a reproductive organ—it’s a microcosm of life’s resilience and adaptability.

Inoculating Grain with Spores: A Comprehensive Guide to the Process

You may want to see also

Alternation of Generations

Land plants, from mosses to flowering trees, exhibit a fascinating reproductive strategy known as alternation of generations. This process involves the cyclical transition between two distinct phases: the sporophyte generation, which produces spores via meiosis, and the gametophyte generation, which produces gametes (sperm and eggs) through mitosis. Understanding this alternation is crucial for grasping how land plants ensure genetic diversity and adapt to diverse environments.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a classic example of alternation of generations. The visible fern plant is the sporophyte, a diploid organism that produces haploid spores in structures called sporangia. These spores, formed through meiosis, develop into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes (prothalli) that are often hidden beneath the soil or leaf litter. The gametophyte generation is short-lived but critical, as it produces gametes that fuse to form a new sporophyte, completing the cycle. This alternation ensures that each generation experiences different selective pressures, enhancing the species' resilience.

Analyzing this process reveals its evolutionary advantages. Meiosis in the sporophyte phase introduces genetic variation through recombination, while the gametophyte phase allows for rapid adaptation to local conditions. For instance, in bryophytes like mosses, the gametophyte is the dominant generation, thriving in moist environments where it can efficiently produce gametes. In contrast, vascular plants like ferns and angiosperms prioritize the sporophyte generation, which is better suited for resource acquisition and dispersal. This flexibility highlights the adaptability of alternation of generations across diverse plant lineages.

To observe alternation of generations firsthand, start by collecting spores from a mature fern frond. Place the frond in a plastic bag overnight to allow spores to drop onto a paper surface. Sow these spores on a moist, sterile substrate, such as a mixture of soil and sand, kept in a humid environment. Within weeks, you’ll see gametophytes emerge, eventually producing sperm and eggs. Introduce water to facilitate fertilization, and watch as a new sporophyte develops. This simple experiment underscores the elegance of alternation of generations and its role in plant reproduction.

In practical terms, understanding alternation of generations has implications for horticulture and conservation. For example, propagating rare plant species often requires manipulating their life cycles, such as cultivating gametophytes in controlled conditions. Additionally, recognizing the vulnerability of gametophytes to environmental changes can inform strategies for protecting endangered plants. By appreciating the intricacies of this reproductive strategy, we gain insights into the resilience and diversity of land plants, ensuring their survival in a changing world.

Can Dehumidifiers Kill Mold Spores? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, land plants produce spores through the process of meiosis, which is a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid spores.

Meiosis is necessary for spore production because it ensures genetic diversity and maintains the alternation of generations in land plants, allowing for the formation of haploid gametophytes and diploid sporophytes.

Spores form via meiosis during the sporophyte phase of the plant life cycle, where diploid cells undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores.

Yes, all spores produced by land plants are the result of meiosis, as it is the only process that reduces the chromosome number to create haploid cells.

After being produced by meiosis, spores germinate to form haploid gametophytes, which then produce gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction, continuing the plant life cycle.

![Shirayuri Koji [Aspergillus oryzae] Spores Gluten-Free Vegan - 10g/0.35oz](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61ntibcT8gL._AC_UL320_.jpg)