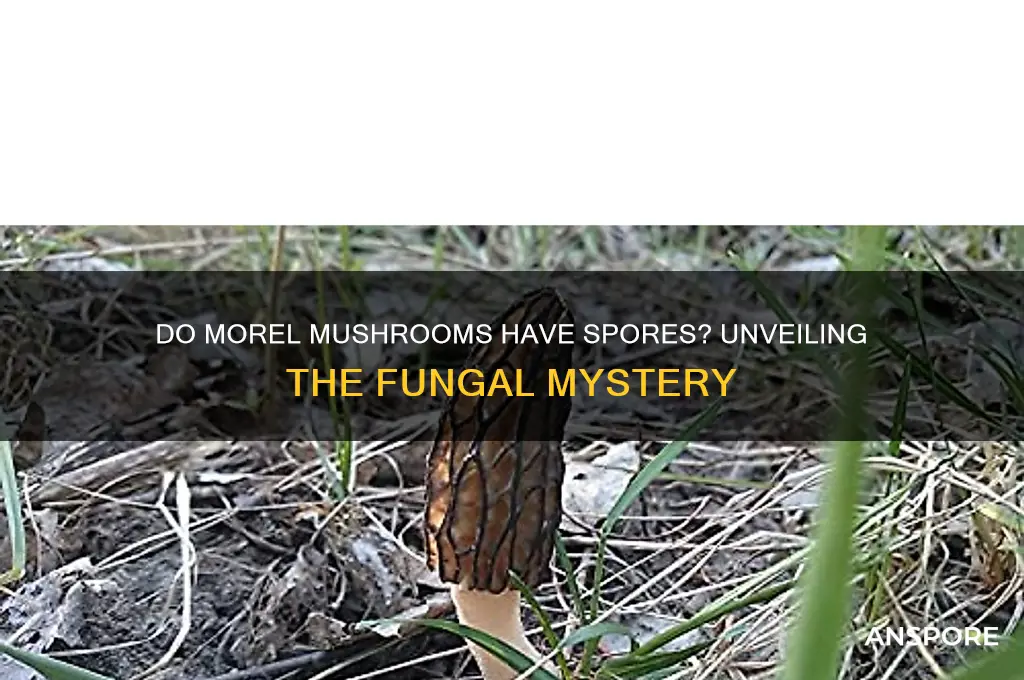

Morel mushrooms, prized for their unique honeycomb-like appearance and rich, earthy flavor, are a fascinating subject in the world of mycology. One of the most intriguing aspects of these fungi is their reproductive mechanism, which involves the production and dispersal of spores. Unlike plants that rely on seeds, morels, like other mushrooms, reproduce through spores, which are microscopic, single-celled structures released into the environment. These spores play a crucial role in the life cycle of morels, allowing them to propagate and colonize new areas. Understanding whether morel mushrooms have spores is fundamental to appreciating their biology, as well as their cultivation and foraging practices.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spores Presence | Yes |

| Spore Type | Ascospores (produced within sac-like structures called asci) |

| Spore Color | Cream to pale yellow or brown (depending on species) |

| Spore Shape | Elliptical or oval |

| Spore Size | Typically 20-30 µm in length |

| Spore Release | Released through apical pores in the ascus |

| Spore Function | Reproduction and dispersal |

| Spore Production Location | Inside the honeycomb-like pits and ridges of the morel cap |

| Spore Viability | Viable for several years under suitable conditions |

| Ecological Role | Essential for the mushroom's life cycle and ecosystem contribution |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Morel spore structure: Unique, ridged, and honeycomb-like, morel spores are distinct from other mushrooms

- Spore dispersal methods: Morels release spores through wind, water, and animal contact for propagation

- Spore color and size: Typically yellow-brown, morel spores are 20-30 µm in diameter

- Spore role in identification: Spores help differentiate true morels from false morels in classification

- Spore viability and growth: Morel spores require specific conditions to germinate and form mycelium

Morel spore structure: Unique, ridged, and honeycomb-like, morel spores are distinct from other mushrooms

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers and chefs alike, are not just another fungus in the forest. Their spores, the microscopic units of reproduction, are a marvel of nature. Unlike the smooth, round spores of many other mushrooms, morel spores are uniquely ridged and honeycomb-like in structure. This distinct shape is not merely a curiosity—it plays a crucial role in their dispersal and survival. When examining morel spores under a microscope, the intricate ridges become apparent, resembling a tiny, natural work of art. This structure is a key identifier for mycologists and foragers, setting morels apart from look-alike species.

To understand the significance of morel spore structure, consider their function in reproduction. The ridges and honeycomb pattern increase the surface area of the spore, enhancing its ability to catch air currents and travel farther distances. This adaptation is particularly advantageous for morels, which often grow in scattered clusters and rely on wind dispersal to colonize new areas. For foragers, recognizing this unique spore structure can be a valuable tool in identifying true morels, as some toxic mushrooms, like the false morel, lack these distinctive features. A simple spore print—made by placing the cap on dark paper overnight—can reveal these ridges, aiding in accurate identification.

From a practical standpoint, understanding morel spore structure can also improve cultivation efforts. While morels are notoriously difficult to grow, knowledge of their spore morphology can inform techniques for spore germination and mycelium development. For instance, creating a humid, well-aerated environment mimics the natural conditions under which morel spores thrive. Additionally, using a microscope to inspect spores for viability before planting can increase the success rate of cultivation attempts. This analytical approach transforms the art of morel cultivation into a more precise science.

Comparatively, the spore structure of morels stands in stark contrast to that of common button mushrooms or shiitakes, whose spores are smooth and lack such complexity. This difference highlights the evolutionary adaptations of morels to their specific ecological niche. While other mushrooms may rely on animals or water for spore dispersal, morels have evolved a structure optimized for wind travel. This comparison underscores the uniqueness of morels not just in their flavor and appearance, but also in their biological design.

In conclusion, the ridged, honeycomb-like structure of morel spores is a testament to the ingenuity of nature. It serves as a functional adaptation for dispersal, a diagnostic feature for identification, and a key to unlocking cultivation techniques. For anyone fascinated by fungi, the morel spore is a microcosm of complexity and beauty, offering both practical and scientific insights into one of the forest’s most enigmatic mushrooms. Whether you’re a forager, a chef, or a mycologist, understanding this structure deepens your appreciation for the remarkable morel.

Does 409 Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores? A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Spore dispersal methods: Morels release spores through wind, water, and animal contact for propagation

Morels, those prized fungi of the forest floor, rely on a trio of dispersal methods to spread their spores and ensure the continuation of their species. Wind, the most ubiquitous of these methods, carries spores aloft in a passive dance, scattering them across vast distances. This aerial dispersal is particularly effective for morels due to their spore-producing structures, which are located within the honeycomb-like pits and ridges of their caps. When the wind gusts through these intricate folds, it dislodges spores, propelling them into the surrounding environment. Foraging enthusiasts should note that windy days after a morel bloom can significantly reduce the number of visible mushrooms, as spores are dispersed and new growth is initiated elsewhere.

Water, though less immediate in its impact, plays a crucial role in spore dispersal, especially in humid environments where morels thrive. Raindrops falling on mature morels can splash spores from the caps, carrying them to nearby soil or water bodies. This method is particularly effective in wooded areas with streams or damp ground, where water acts as a secondary vector for spore distribution. Gardeners and mycologists can mimic this natural process by gently misting mature morels in controlled environments to encourage spore release and collection for cultivation purposes.

Animal contact, often overlooked, is a fascinating and vital dispersal mechanism. Small mammals, insects, and even birds can inadvertently transport morel spores as they forage or move through the forest. Spores cling to fur, feathers, or exoskeletons and are deposited in new locations as these creatures travel. For instance, a squirrel nibbling on a morel might carry spores to its nest, inadvertently planting the next generation of fungi. This symbiotic relationship highlights the interconnectedness of forest ecosystems and underscores the importance of preserving biodiversity for fungal propagation.

Understanding these dispersal methods not only deepens our appreciation for morels but also informs practical strategies for cultivation and conservation. Foraging responsibly—avoiding overharvesting and leaving some mushrooms to release spores—ensures the sustainability of morel populations. Cultivators can harness these natural mechanisms by creating environments that mimic wind, water, and animal interactions, increasing the success rate of spore germination. Whether you’re a forager, gardener, or simply a nature enthusiast, recognizing the ingenuity of morel spore dispersal adds a layer of wonder to these already captivating fungi.

Can Rubbing Alcohol Effectively Kill Bacterial Spores? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Spore color and size: Typically yellow-brown, morel spores are 20-30 µm in diameter

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers and chefs alike, produce spores that are as distinctive as the fungi themselves. These spores, typically yellow-brown in color, serve as the mushroom’s reproductive units, dispersing to propagate new growth. Their size is equally notable, measuring between 20 and 30 micrometers (µm) in diameter—a detail crucial for identification under a microscope. This combination of color and size not only aids mycologists in classification but also helps foragers distinguish morels from false look-alikes, ensuring safe and accurate harvesting.

For those interested in studying morel spores, a simple yet effective method involves creating a spore print. Place the cap of a mature morel on a piece of dark paper or glass, cover it with a bowl, and leave it undisturbed for 24 hours. The resulting print will reveal the characteristic yellow-brown spores, providing a visual confirmation of the mushroom’s identity. This technique is particularly useful for beginners learning to differentiate morels from toxic species like the false morel, whose spores differ in color and structure.

The size of morel spores, at 20-30 µm, places them in a range easily observable under a basic light microscope with a 40x objective lens. Foragers and enthusiasts can invest in a beginner’s microscope kit, often available for under $100, to examine spore details firsthand. When preparing a slide, gently crush a small portion of the mushroom’s cap in a drop of water, spread it thinly, and cover with a slip. This allows for clear observation of spore shape, color, and size, enhancing confidence in identification.

Beyond identification, understanding spore color and size has practical implications for cultivation. Morel spores are commercially available for inoculating substrate, but success rates vary. The yellow-brown spores are sensitive to environmental conditions, requiring specific temperature (15-20°C) and humidity (70-80%) ranges for germination. Hobbyists should note that while spore size is consistent, viability decreases with age, so using fresh spores within six months of purchase maximizes the chances of successful fruiting.

In the broader context of mycology, the yellow-brown spores of morels stand out among fungi, which often produce white, black, or green spores. This uniqueness reflects the morel’s specialized ecological niche as a saprotroph, breaking down organic matter in forest floors. For educators and parents, demonstrating spore color and size can be an engaging way to introduce children (ages 8 and up) to the wonders of fungi, using simple tools like a magnifying glass or microscope to spark curiosity about the natural world.

Can CBD Treat Lung Spores? Exploring Potential Benefits and Research

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore role in identification: Spores help differentiate true morels from false morels in classification

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers for their distinctive flavor and texture, are often confused with their toxic look-alikes, false morels. One of the most reliable ways to distinguish between the two is by examining their spores. True morels (genus *Morchella*) produce spores that are smooth, elliptical, and typically measure between 17–25 μm in length. These spores are released from the mushroom’s honeycomb-like cap and are a key feature in identification. False morels, on the other hand, often belong to the genus *Gyromitra* and produce spores that are larger, rougher, and more irregular in shape. This fundamental difference in spore morphology serves as a critical diagnostic tool for mycologists and experienced foragers alike.

To identify morels using spores, follow these steps: First, collect a mature specimen, ensuring the cap is fully developed and the spores are mature. Next, place the cap on a piece of dark paper or glass for several hours to allow spores to drop. Examine the spore print under a microscope, noting their size, shape, and texture. Smooth, elliptical spores strongly indicate a true morel, while rough or irregular spores suggest a false morel. Caution: Never rely solely on spore identification for consumption; always cross-reference with other morphological features and consult a field guide or expert.

The analytical approach to spore identification highlights its precision but also underscores its limitations. While spores are a definitive characteristic, they require specialized equipment and knowledge to interpret accurately. For instance, a novice forager might struggle to distinguish between a 20 μm *Morchella* spore and a 25 μm *Gyromitra* spore without proper training. Additionally, environmental factors like humidity and temperature can affect spore release, complicating the process. Despite these challenges, spore analysis remains a cornerstone of morel classification, offering a level of certainty that visual inspection alone cannot provide.

From a persuasive standpoint, understanding spore differences empowers foragers to make safer choices. False morels contain gyromitrin, a toxin that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress or even organ failure if ingested. By mastering spore identification, foragers reduce the risk of misidentification, ensuring their harvest is both delicious and safe. Practical tips include investing in a beginner’s microscope (around $50–$100) and practicing spore collection on known species before attempting identification in the wild. This proactive approach transforms spore analysis from a scientific technique into a life-saving skill.

Finally, a comparative perspective reveals the broader implications of spore identification. While true and false morels share superficial similarities, their spores reflect deeper evolutionary divergences. True morels belong to the family Morchellaceae, known for their symbiotic relationships with trees, while false morels in the family Discinaceae often decompose organic matter. This ecological distinction, mirrored in spore structure, highlights the interconnectedness of morphology, taxonomy, and habitat. For foragers, this knowledge not only aids in identification but also deepens their appreciation for the fungi they seek, transforming a simple hunt into a journey of discovery.

Comparing Selaginella Spore Sizes: Are They Uniform Across Species?

You may want to see also

Spore viability and growth: Morel spores require specific conditions to germinate and form mycelium

Morel spores are not just present; they are the lifeblood of these elusive fungi, yet their journey from spore to mycelium is fraught with environmental demands. Unlike common mushrooms, morel spores require a precise combination of moisture, temperature, and substrate to germinate successfully. For instance, a soil pH between 6.0 and 7.5 is ideal, and temperatures must hover around 60–70°F (15–21°C) for optimal viability. Without these conditions, spores remain dormant, underscoring the delicate balance needed for their growth.

To cultivate morel spores, start by preparing a nutrient-rich substrate, such as well-rotted hardwood mulch or straw, which mimics their natural forest habitat. Inoculate the substrate with spore slurry, ensuring even distribution. Maintain humidity levels above 70% and avoid direct sunlight, as morels thrive in shaded, moist environments. A pro tip: lightly mist the substrate daily to prevent drying, but avoid overwatering, as waterlogged conditions can suffocate the developing mycelium.

Comparatively, morel spores are less forgiving than those of button mushrooms or oyster mushrooms, which can germinate under broader conditions. Morel mycelium growth is slow, often taking 6–12 months to establish before fruiting bodies appear. This extended timeline highlights the patience required for successful cultivation. For hobbyists, using a sterile environment during inoculation can significantly reduce contamination risks, though this step is less critical for outdoor beds.

A critical caution: morel spores are highly sensitive to chemical exposure. Avoid using pesticides or fertilizers near inoculated areas, as these can inhibit spore germination or kill mycelium. Additionally, while morels are prized for their flavor, not all "morel-like" mushrooms are safe to eat. Always verify species identification before consuming, as false morels can be toxic. This dual need for precision in cultivation and caution in harvesting underscores the unique challenges of working with morel spores.

In conclusion, mastering morel spore viability and growth demands attention to detail and respect for their ecological niche. By replicating their natural conditions and avoiding common pitfalls, cultivators can unlock the potential of these spores, transforming them from microscopic entities into prized culinary treasures. Whether for personal enjoyment or commercial cultivation, understanding these requirements is the first step toward a successful morel harvest.

Are Resting Spores Infectious? Unveiling Their Role in Disease Transmission

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, morel mushrooms produce and release spores as part of their reproductive process.

Morel mushrooms release spores through tiny openings called pores or ridges on their honeycomb-like caps.

No, morel mushroom spores are microscopic and cannot be seen without a magnifying tool or microscope.

Yes, morel mushroom spores can be used for cultivation, but growing morels from spores is challenging and often requires specific conditions.

No, morel mushroom spores are not harmful to humans, but it’s important to properly identify and cook morels before consumption to avoid confusion with toxic look-alikes.