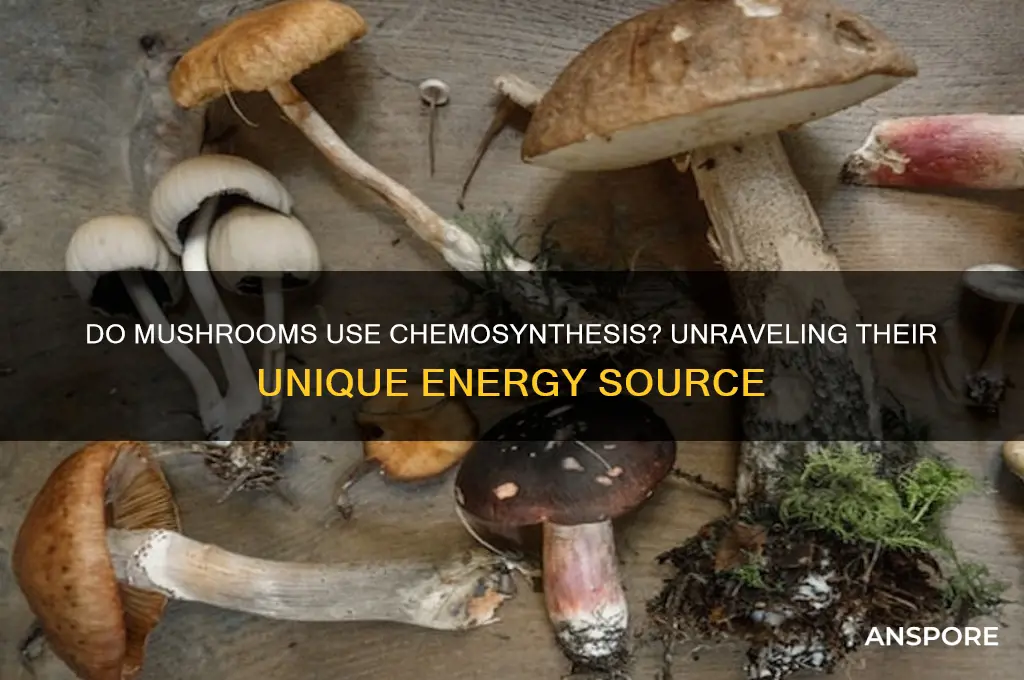

Mushrooms, as fungi, primarily obtain nutrients through the absorption of organic matter from their environment, a process distinct from chemosynthesis. Chemosynthesis is a biological process used by certain bacteria and archaea to convert inorganic chemicals into organic compounds, typically in environments lacking sunlight, such as deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Unlike these microorganisms, mushrooms do not possess the necessary enzymes or metabolic pathways to harness chemical energy in this manner. Instead, they rely on decomposing dead organic material or forming symbiotic relationships with plants through mycorrhizal associations. Therefore, while chemosynthesis is crucial for some life forms in extreme ecosystems, it is not a mechanism utilized by mushrooms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do mushrooms use chemosynthesis? | No |

| Primary energy source for mushrooms | Heterotrophic organisms that obtain energy by decomposing organic matter (saprotrophs) or forming symbiotic relationships with plants (mycorrhizae) |

| Process used by mushrooms to obtain energy | Cellular respiration (breaking down glucose and other organic compounds) |

| Organisms that use chemosynthesis | Certain bacteria and archaea, typically found in extreme environments like hydrothermal vents and deep-sea ecosystems |

| Energy source for chemosynthetic organisms | Inorganic chemicals (e.g., hydrogen sulfide, methane) |

| Key difference between mushrooms and chemosynthetic organisms | Mushrooms rely on organic matter, while chemosynthetic organisms use inorganic chemicals as an energy source |

| Role of mushrooms in ecosystems | Decomposers, breaking down dead organic material and recycling nutrients |

| Examples of chemosynthetic ecosystems | Hydrothermal vents, cold seeps, and cave systems |

| Examples of mushroom habitats | Forests, grasslands, and various terrestrial ecosystems |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Chemosynthetic bacteria in mushrooms

Mushrooms, often associated with decomposing organic matter, have a more complex relationship with their environment than commonly understood. While they are primarily known for their role in breaking down dead plant material through saprotrophic processes, recent research has shed light on a fascinating aspect of their biology: the potential involvement of chemosynthetic bacteria. These bacteria, capable of converting inorganic compounds into organic matter, have been found in association with certain mushroom species, raising questions about the extent of this symbiotic relationship and its implications for fungal ecology.

The Symbiotic Connection

Chemosynthetic bacteria thrive in environments where sunlight is scarce, relying on chemical energy from compounds like hydrogen sulfide, methane, or ammonia. In mushrooms, these bacteria are often located in the mycelium or fruiting bodies, suggesting a mutualistic partnership. For instance, studies have identified sulfur-oxidizing bacteria in species like *Armillaria* and *Laccaria*, which inhabit nutrient-poor soils. The bacteria convert sulfur compounds into usable forms, potentially providing the mushroom with essential nutrients in exchange for protection and habitat. This symbiotic relationship mirrors those found in deep-sea hydrothermal vents, where chemosynthetic bacteria sustain entire ecosystems.

Mechanisms and Benefits

The interaction between mushrooms and chemosynthetic bacteria is not merely coincidental but appears to be a strategic adaptation. The bacteria’s ability to fix nitrogen or oxidize sulfur can enhance the mushroom’s access to nutrients in otherwise inhospitable environments. For example, in boreal forests, *Laccaria bicolor* associates with sulfur-oxidizing bacteria to thrive in soils low in organic matter. This partnership allows the mushroom to colonize areas where other fungi might struggle, giving it a competitive edge. Understanding these mechanisms could revolutionize our approach to fungal cultivation, particularly in nutrient-deficient substrates.

Practical Applications and Cautions

For mycologists and hobbyists, leveraging chemosynthetic bacteria in mushroom cultivation could open new possibilities. Introducing sulfur-rich substrates or inoculating mycelium with specific bacterial strains might enhance growth in challenging conditions. However, caution is necessary. Over-reliance on chemosynthetic bacteria could disrupt natural fungal processes, and the long-term effects of such interventions remain poorly understood. Additionally, not all mushroom species benefit from these bacteria, so targeted research is essential. For instance, *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushrooms) may not require such symbiosis, while *Morchella* (morels) could potentially benefit from nitrogen-fixing bacteria.

Future Directions

The study of chemosynthetic bacteria in mushrooms is still in its infancy, but its potential is vast. Researchers are exploring how these partnerships could be harnessed for bioremediation, such as using mushrooms to clean up sulfur-contaminated soils. Furthermore, understanding this symbiosis could lead to innovations in sustainable agriculture, where fungi and bacteria work together to improve soil health. As we uncover more about this hidden collaboration, it becomes clear that mushrooms are not just decomposers but active participants in complex ecological networks, reshaping our understanding of fungal biology.

Should You Use an Incubator for Growing Mushrooms at Home?

You may want to see also

Energy sources for mushroom growth

Mushrooms, unlike plants, do not harness sunlight through photosynthesis. Instead, they rely on external organic matter for energy, primarily through saprophyte or parasitic relationships. Saprophytic mushrooms decompose dead plant and animal material, breaking it down into simpler compounds to fuel their growth. Parasitic mushrooms, on the other hand, derive nutrients from living hosts, often causing harm in the process. This fundamental distinction raises the question: could mushrooms utilize chemosynthesis, a process where organisms convert inorganic chemicals into energy, as some bacteria do in extreme environments?

Chemosynthesis, typically associated with deep-sea hydrothermal vents and cave systems, involves bacteria that oxidize compounds like hydrogen sulfide or methane to produce energy. While mushrooms share a symbiotic relationship with bacteria in certain ecosystems (e.g., mycorrhizal fungi partnering with plant roots), there is no scientific evidence to suggest mushrooms themselves employ chemosynthesis. Their energy acquisition remains rooted in organic matter, not inorganic chemical reactions. For instance, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) thrive on lignin-rich substrates like straw, while shiitake mushrooms (*Lentinula edodes*) prefer hardwood logs, showcasing their adaptability to diverse organic sources.

To cultivate mushrooms effectively, understanding their energy requirements is crucial. For home growers, substrates like sawdust, coffee grounds, or grain provide ample organic material. For example, a 5-gallon bucket of pasteurized straw inoculated with oyster mushroom spawn can yield up to 2 pounds of mushrooms within 4–6 weeks, given optimal humidity (60–70%) and temperature (65–75°F). Avoid over-saturating the substrate, as excessive moisture can lead to bacterial contamination. For parasitic species like *Armillaria*, ensure they are cultivated in controlled environments to prevent harm to unintended hosts.

Comparatively, while chemosynthetic bacteria thrive in nutrient-poor, extreme conditions, mushrooms flourish in environments rich in organic debris. This contrast highlights the evolutionary divergence in energy strategies. For instance, bacteria near hydrothermal vents rely on sulfur compounds, whereas mushrooms in a forest floor ecosystem depend on fallen leaves and wood. Both systems are efficient but tailored to their respective niches, underscoring the diversity of life’s energy pathways.

In conclusion, while mushrooms do not use chemosynthesis, their saprophytic and parasitic strategies are remarkably efficient for their ecological roles. By focusing on organic substrates, growers can harness their natural energy sources to cultivate mushrooms sustainably. Whether decomposing agricultural waste or enriching forest soils, mushrooms exemplify nature’s ingenuity in transforming organic matter into life.

Did Vikings Use Mushrooms? Unveiling Ancient Nordic Fungal Secrets

You may want to see also

Role of sulfur compounds

Sulfur compounds play a pivotal role in chemosynthesis, a process where certain organisms harness inorganic chemicals to produce organic matter. While mushrooms are not typically associated with chemosynthesis, some fungi, particularly those in extreme environments, exhibit behaviors that hint at sulfur-driven metabolic adaptations. These sulfur compounds, such as hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) and elemental sulfur (S), serve as electron donors in chemosynthetic pathways, enabling energy production in the absence of sunlight. For instance, fungi in hydrothermal vents or sulfur-rich soils may utilize these compounds to sustain their metabolic needs, blurring the lines between traditional fungal biology and chemosynthetic processes.

To understand the role of sulfur compounds in such contexts, consider the steps involved in their utilization. First, fungi must access sulfur sources, often through mycorrhizal associations or direct absorption from the environment. Second, enzymes like sulfur reductases convert sulfur compounds into usable forms, such as sulfides. Finally, these reduced sulfur species enter metabolic pathways, potentially contributing to ATP production or biosynthetic processes. For example, the fungus *Cicer arietinum* has been studied for its ability to reduce sulfate, a process that could theoretically support chemosynthesis-like activities under specific conditions.

However, caution must be exercised when extrapolating these findings to all mushrooms. Not all fungi possess the genetic or enzymatic machinery to utilize sulfur compounds for energy. Dosage and environmental factors also play critical roles. High concentrations of sulfur compounds, such as 1-5 mM H₂S, can be toxic to most fungi, while lower concentrations (0.1-0.5 mM) may stimulate growth in specialized species. Practical tips for researchers include cultivating fungi in controlled environments with varying sulfur concentrations to observe metabolic responses and using molecular techniques to identify sulfur-metabolizing genes.

Comparatively, sulfur-based chemosynthesis in fungi differs from that in bacteria and archaea, which are well-documented chemosynthesizers. While bacteria like *Beggiatoa* directly oxidize sulfur compounds for energy, fungi may use these processes indirectly or in conjunction with other metabolic strategies. This distinction highlights the unique evolutionary adaptations of fungi, which often thrive in symbiotic relationships rather than relying solely on inorganic compounds. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi in sulfur-rich soils may benefit from plant-derived carbon while utilizing sulfur for secondary metabolism.

In conclusion, the role of sulfur compounds in fungal metabolism opens intriguing possibilities for understanding chemosynthesis-like processes in mushrooms. While not all fungi engage in this behavior, those that do provide valuable insights into the versatility of fungal adaptations. Practical applications, such as bioremediation of sulfur-contaminated soils or biotechnological production of sulfur-based compounds, underscore the importance of further research. By focusing on specific sulfur-metabolizing fungi and their environmental interactions, scientists can uncover new dimensions of fungal biology and its potential contributions to chemosynthetic ecosystems.

Were Ancient Mushrooms Gigantic? Unveiling the Mystery of Prehistoric Fungi

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mushrooms in extreme environments

Mushrooms thrive in environments that would be inhospitable to most life forms, from radioactive zones to arid deserts. Take the species *Cladosporium sphaerospermum*, found growing inside the damaged Chernobyl reactor, where it metabolizes gamma radiation as an energy source. This phenomenon, known as radiosynthesis, challenges traditional notions of fungal survival mechanisms. Unlike chemosynthesis, which relies on inorganic chemicals like hydrogen sulfide, radiosynthesis harnesses ionizing radiation to drive biochemical processes. Such adaptations highlight mushrooms’ ability to exploit extreme energy sources, positioning them as pioneers in Earth’s most unforgiving habitats.

In the arid Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth, *Fusarium* and *Exophiala* species endure near-zero humidity and intense UV radiation. These fungi enter cryptobiotic states, suspending metabolic activity until moisture returns. While they do not use chemosynthesis, their survival strategies—such as melanin production to shield against radiation—demonstrate a parallel ingenuity in resource utilization. For enthusiasts studying extremophiles, cultivating such species requires simulating harsh conditions: use silica gel to maintain low humidity and UV lamps to replicate solar exposure, ensuring the fungi’s dormant mechanisms are preserved.

Deep-sea hydrothermal vents, with temperatures exceeding 350°C and sulfur-rich waters, host fungi like *Exidiopsis* that coexist with chemosynthetic bacteria. Here, mushrooms do not directly perform chemosynthesis but form symbiotic relationships with bacteria that do. This mutualism allows fungi to access nutrients in otherwise barren environments. For researchers, replicating vent conditions involves pressurized aquariums with heated, sulfur-infused water. Caution: handling sulfur compounds requires ventilation to avoid toxic fumes, and water temperatures must be monitored to prevent equipment damage.

In permafrost regions, *Mortierella* and *Cryptococcus* species remain metabolically active at subzero temperatures, producing cold-resistant enzymes. These fungi do not rely on chemosynthesis but instead metabolize organic matter trapped in ice. To study their resilience, freeze samples at -20°C and gradually thaw them, observing enzyme activity using spectrophotometric assays. Practical tip: use glycerol as a cryoprotectant to preserve fungal cells during freezing, ensuring structural integrity for analysis.

From radioactive ruins to ocean depths, mushrooms redefine the boundaries of life by mastering survival in extremes. While chemosynthesis remains a bacterial domain, fungi adapt through radiation exploitation, cryptobiosis, symbiosis, and cold tolerance. Each strategy offers insights into biotechnology, from radiation-resistant materials to cold-active enzymes. For those exploring these frontiers, precision in replicating extreme conditions is key—whether through UV exposure, sulfur infusion, or cryogenic storage. Mushrooms in these environments are not just survivors; they are blueprints for innovation in science and industry.

Prince and Psilocybin: Unraveling the Mushroom Mystery in His Life

You may want to see also

Comparison with photosynthesis in fungi

Mushrooms, unlike plants, do not perform photosynthesis. This fundamental difference sets the stage for understanding their unique metabolic processes. While plants harness sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose, mushrooms lack chlorophyll and thus cannot utilize this energy source. Instead, they rely on external organic matter for sustenance, breaking it down through saprotrophic or mycorrhizal relationships. This distinction raises the question: if mushrooms don’t photosynthesize, do they employ chemosynthesis, and how does their energy acquisition compare to that of photosynthetic organisms, particularly within the fungal kingdom?

Chemosynthesis, a process primarily associated with bacteria and some deep-sea organisms, involves using inorganic chemicals as an energy source to produce organic compounds. Fungi, including mushrooms, do not engage in chemosynthesis. Their primary mode of nutrient acquisition is heterotrophic, meaning they obtain energy by decomposing organic material. This contrasts sharply with photosynthetic organisms, which are autotrophic, producing their own food. However, certain fungi form symbiotic relationships with photosynthetic partners, such as in lichens, where algae or cyanobacteria provide carbohydrates through photosynthesis. Here, the fungus benefits indirectly from photosynthesis, but it does not perform the process itself.

The absence of chemosynthesis in mushrooms highlights their evolutionary adaptation to terrestrial environments rich in organic debris. Unlike chemosynthetic bacteria, which thrive in extreme conditions like hydrothermal vents, mushrooms excel in ecosystems where dead plant and animal matter is abundant. Their enzymatic capabilities allow them to break down complex organic compounds, such as lignin and cellulose, which most other organisms cannot digest. This specialization positions them as key decomposers in nutrient cycling, a role distinct from both photosynthetic plants and chemosynthetic bacteria.

Practical observations underscore these differences. For instance, mushrooms grown in controlled environments, such as indoor farms, require organic substrates like straw or wood chips, not inorganic chemicals or light. In contrast, photosynthetic plants need specific light spectrums and carbon dioxide levels. While some fungi, like *Glomeromyces*, form mycorrhizal associations with plant roots to exchange nutrients, this interaction does not involve chemosynthesis or photosynthesis by the fungus. Instead, it showcases the fungus’s ability to enhance plant nutrient uptake, particularly phosphorus, in exchange for photosynthetically derived sugars.

In conclusion, the comparison between fungal metabolism and photosynthesis reveals a clear divergence in energy acquisition strategies. Mushrooms neither photosynthesize nor perform chemosynthesis; they are heterotrophs that rely on external organic matter. This distinction is crucial for understanding their ecological roles and practical applications, such as in agriculture and bioremediation. While fungi may indirectly benefit from photosynthesis through symbiotic relationships, their primary metabolic pathway remains rooted in decomposition, a process that complements rather than mimics photosynthetic or chemosynthetic mechanisms.

Are Pesticides Used on Mushrooms? Uncovering the Truth About Cultivation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, mushrooms do not use chemosynthesis. They primarily obtain energy through the decomposition of organic matter, a process called saprotrophy.

Chemosynthesis is a process where certain organisms convert inorganic chemicals into organic compounds for energy, often in environments lacking sunlight. Mushrooms do not use chemosynthesis because they rely on breaking down dead organic material instead.

While some bacteria and archaea use chemosynthesis, fungi, including mushrooms, do not. Fungi are primarily decomposers and do not possess the necessary enzymes or metabolic pathways for chemosynthesis.

Mushrooms obtain energy by secreting enzymes to break down complex organic materials like cellulose and lignin in dead plants, fungi, and animals, absorbing the nutrients released.

Mushrooms are not adapted to survive in extreme environments like deep-sea vents, where chemosynthetic bacteria thrive. They require organic matter and typically inhabit terrestrial or soil-based ecosystems.