Using mushroom compost in a worm farm is generally not recommended due to its high pH levels and potential residual chemicals from the mushroom cultivation process. Mushroom compost is typically enriched with materials like lime and gypsum, which can create an alkaline environment that is unsuitable for worms, as they thrive in neutral to slightly acidic conditions. Additionally, the compost may contain pesticides or fungicides used during mushroom production, which can harm or kill the worms. While mushroom compost can be beneficial in garden beds, it lacks the organic diversity and microbial balance that worms require for optimal health and reproduction. Instead, worm farms should focus on using a mix of organic materials like vegetable scraps, shredded paper, and garden waste to create a safe and nutrient-rich environment for the worms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| pH Level | Mushroom compost typically has a high pH (around 7.0-8.0), which is too alkaline for worms that prefer a neutral to slightly acidic environment (pH 6.5-7.0). |

| Salt Content | Contains high levels of salts (from added lime and gypsum), which can be harmful or fatal to worms. |

| Chemical Residues | May contain residual pesticides, fungicides, or other chemicals used in mushroom cultivation, posing risks to worms. |

| Nutrient Imbalance | Often lacks balanced nutrients for worms and can lead to an overabundance of certain minerals, disrupting the worm farm ecosystem. |

| Texture | Too fine and dense, reducing airflow and causing compaction, which is unsuitable for worm habitats. |

| Microbial Activity | Contains specialized microbes for mushroom growth, which may compete with or harm beneficial microbes in a worm farm. |

| Ammonia Levels | Can have high ammonia content from decomposition, toxic to worms in concentrated amounts. |

| Heavy Metals | Potential contamination with heavy metals from additives or growing substrates, harmful to worms and their environment. |

| Decomposition Stage | Partially decomposed, requiring further breakdown that may produce heat or conditions unfavorable for worms. |

| Moisture Content | Often too wet, leading to anaerobic conditions and potential mold or bacterial issues in the worm farm. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- High Acidity Levels: Mushroom compost's pH can harm worms, disrupting their sensitive digestive systems

- Toxic Fungicides: Residual chemicals in mushroom compost may kill worms or reduce their lifespan

- Excessive Salt Content: High salt levels in mushroom compost can dehydrate and stress worms

- Lack of Nutrient Balance: Mushroom compost lacks the diverse nutrients worms need for optimal health

- Attracts Pests: Mushroom compost can draw pests like mites, harming the worm farm ecosystem

High Acidity Levels: Mushroom compost's pH can harm worms, disrupting their sensitive digestive systems

Mushroom compost, often hailed for its nutrient-rich properties, can be a double-edged sword when introduced to a worm farm. The primary concern lies in its pH level, which tends to be significantly higher in acidity than what worms can tolerate. Worms thrive in a pH range of 6.5 to 7.5, a slightly acidic to neutral environment that supports their digestive processes. Mushroom compost, however, often falls below this range, sometimes dipping as low as pH 5.5 or lower, due to the materials and processes used in its creation. This acidity can wreak havoc on a worm’s delicate digestive system, impairing their ability to process food and absorb nutrients effectively.

The impact of high acidity on worms is not merely theoretical; it manifests in observable ways. Worms exposed to acidic environments may exhibit reduced feeding activity, slower reproduction rates, and even physical distress, such as skin irritation or inflammation. Over time, prolonged exposure to acidic conditions can lead to population decline or even mortality. For instance, a study found that worms in soil with a pH of 5.0 showed a 40% decrease in biomass compared to those in neutral soil. This highlights the critical importance of monitoring pH levels when considering bedding materials for a worm farm.

To mitigate the risks associated with mushroom compost, worm farmers should prioritize pH testing before incorporating any new material. Simple pH test kits, available at garden supply stores, can provide quick and accurate readings. If the compost’s pH is below 6.5, it should be avoided or amended to raise the pH. One practical method is to mix the compost with calcium-rich materials like crushed eggshells, agricultural lime, or wood ash. For example, adding 1 cup of agricultural lime per 5 gallons of compost can help neutralize acidity, but it’s essential to retest the pH after amendment to ensure it falls within the safe range.

Comparatively, alternative bedding materials such as coconut coir, shredded cardboard, or aged manure offer a safer, more stable environment for worms. These materials typically have pH levels closer to neutral and lack the chemical residues often found in mushroom compost. While mushroom compost may seem appealing due to its nutrient content, the potential harm to worms far outweighs the benefits. Worm farmers should prioritize the health and longevity of their colonies by opting for pH-balanced materials and avoiding the risks associated with high-acidity composts.

In conclusion, the high acidity of mushroom compost poses a significant threat to the well-being of worms in a farm setting. By understanding the pH requirements of worms and taking proactive steps to test and amend materials, farmers can create a thriving environment for their colonies. The key takeaway is clear: when it comes to worm farming, pH matters, and mushroom compost is not worth the risk.

Prince and Psilocybin: Unraveling the Mushroom Mystery in His Life

You may want to see also

Toxic Fungicides: Residual chemicals in mushroom compost may kill worms or reduce their lifespan

Mushroom compost, a byproduct of mushroom farming, often contains residual fungicides that can be lethal to worms. These chemicals, designed to suppress fungal growth in mushroom beds, persist in the compost even after the mushrooms are harvested. Worms, being highly sensitive to environmental toxins, can suffer severe consequences when exposed to these substances. For instance, chlorothalonil, a common fungicide used in mushroom cultivation, has been shown to reduce worm survival rates by up to 70% in controlled studies. This highlights the critical need to avoid using mushroom compost in worm farms without proper treatment or testing.

To understand the risk, consider the lifecycle of mushroom compost. After mushrooms are grown, the spent substrate is often sold or repurposed. However, fungicides like carbendazim and iprodione, which are widely used in mushroom farming, can remain active in the compost for months. Worms exposed to these chemicals may exhibit symptoms such as reduced feeding, lethargy, and increased mortality. Even low concentrations, as little as 10 parts per million (ppm), can significantly impact worm health. This makes it essential to test mushroom compost for residual chemicals before introducing it to a worm farm.

If you’re determined to use mushroom compost in your worm farm, follow these steps to mitigate risks. First, source compost from organic mushroom farms that avoid synthetic fungicides. Second, conduct a bioassay by introducing a small sample of the compost to a test group of worms and monitoring their health over two weeks. Third, if residual chemicals are detected, consider aging the compost for at least six months to allow natural degradation of the fungicides. Alternatively, leach the compost by soaking it in water for 48 hours, discarding the runoff, and repeating the process twice to reduce chemical concentrations.

Comparing mushroom compost to safer alternatives underscores its risks. Unlike coconut coir or aged manure, which are free from toxic residues, mushroom compost requires careful handling. For example, a study comparing worm survival in mushroom compost versus coconut coir found that worms in the latter thrived, while those in the former experienced a 50% mortality rate within 30 days. This stark contrast emphasizes the importance of prioritizing worm safety over convenience. If in doubt, opt for bedding materials with a proven track record of safety.

Finally, the long-term impact of toxic fungicides on worm farms cannot be overstated. Worms play a vital role in composting by breaking down organic matter and enriching soil. However, exposure to residual chemicals not only reduces their lifespan but also compromises their ability to process waste efficiently. This can lead to slower composting rates and poorer soil quality. By avoiding mushroom compost or treating it properly, you protect your worms and ensure the sustainability of your composting system. Always prioritize the health of your worms, as they are the cornerstone of a successful worm farm.

Do Drug Tests Detect Psilocybin Mushrooms? What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Excessive Salt Content: High salt levels in mushroom compost can dehydrate and stress worms

Mushroom compost, often rich in nutrients, seems like an ideal addition to a worm farm. However, its high salt content can be detrimental to worms, leading to dehydration and stress. This issue arises from the materials used in mushroom cultivation, such as straw, gypsum, and chicken manure, which contribute to elevated salt levels. Worms, being highly sensitive to their environment, struggle to thrive in such conditions, making mushroom compost a poor choice for their habitat.

To understand the impact, consider that worms regulate their body fluids through a permeable skin, which is highly susceptible to external salinity. When exposed to high salt concentrations, osmosis causes water to leave their bodies, leading to dehydration. A study found that salt levels above 1.5% in worm bedding can significantly reduce their survival rate. Mushroom compost often exceeds this threshold, with salt content ranging from 2% to 4%, depending on its composition. This disparity highlights the incompatibility between mushroom compost and worm farms.

Addressing this issue requires proactive measures. If you’re determined to use mushroom compost, leaching is essential. Soak the compost in water for 24–48 hours, changing the water periodically to remove excess salts. Test the leachate with a salinity meter; aim for a reading below 1.5%. Alternatively, mix mushroom compost with low-salt materials like coconut coir or aged manure to dilute its salinity. However, these steps are labor-intensive and may not fully mitigate the risk, making avoidance the safer option.

Comparing mushroom compost to worm-friendly alternatives underscores its unsuitability. Materials like shredded cardboard, leaf mold, or aged vegetable scraps provide a low-salt environment conducive to worm health. These options not only avoid dehydration but also support optimal worm reproduction and composting efficiency. While mushroom compost might seem nutrient-rich, its salt content outweighs any potential benefits for a worm farm ecosystem.

In conclusion, the excessive salt content in mushroom compost poses a significant threat to worms, disrupting their hydration and overall well-being. While mitigation strategies exist, they are often impractical and unreliable. Prioritizing worm-safe bedding materials ensures a thriving, stress-free environment for these essential decomposers. Avoid mushroom compost in worm farms to protect your worms and maintain a productive system.

Do Mushrooms Use Chemosynthesis? Unraveling Their Unique Energy Source

You may want to see also

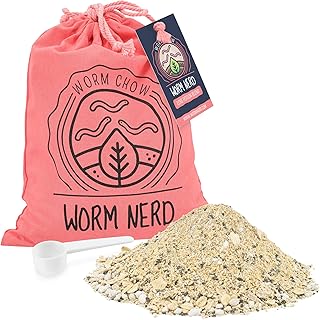

Explore related products

$12.49

$18.99

Lack of Nutrient Balance: Mushroom compost lacks the diverse nutrients worms need for optimal health

Mushroom compost, while nutrient-rich, is tailored to the specific needs of fungi, not worms. Its composition often includes high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus, which can create an imbalanced environment for worms. These organisms thrive in a diverse nutrient profile, requiring a mix of carbon, nitrogen, and trace minerals in precise ratios. Mushroom compost’s specialized formulation falls short, lacking the variety of organic matter worms need to process and digest efficiently. This imbalance can lead to poor worm health, reduced reproduction rates, and diminished composting efficiency.

Consider the dietary analogy: feeding a human solely on protein would result in malnutrition despite the nutrient’s importance. Similarly, mushroom compost’s narrow nutrient spectrum fails to meet worms’ holistic needs. Worms require a blend of cellulose, lignin, and other organic compounds to maintain their gut microbiome and overall vitality. Mushroom compost, often dominated by straw and gypsum, lacks the diversity of kitchen scraps, yard waste, or aged manure that worms naturally process. Without this variety, worms may struggle to extract essential nutrients, leading to stunted growth and weakened immune systems.

Practical observation reveals the consequences of this imbalance. Worm farmers who introduce mushroom compost often notice slower decomposition rates and a decline in worm activity. The compost’s high salt content, a byproduct of mushroom cultivation, can further stress worms, causing them to avoid treated areas. To mitigate this, limit mushroom compost to no more than 10% of your worm bedding, and always mix it with carbon-rich materials like shredded paper or coconut coir. Gradually introduce small amounts while monitoring worm behavior to ensure they adapt without distress.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between mushroom compost and ideal worm bedding. While mushroom compost is designed to retain moisture and suppress pathogens for fungi, worms require a more breathable, varied substrate. Alternatives like leaf mold, composted manure, or peat moss offer a broader nutrient range and better aeration. These materials mimic worms’ natural habitats, promoting robust health and prolific reproduction. By prioritizing diversity over convenience, worm farmers can avoid the pitfalls of nutrient imbalance and foster a thriving vermicomposting system.

Mushrooms' Unique Survival: Do They Thrive Without Light?

You may want to see also

Attracts Pests: Mushroom compost can draw pests like mites, harming the worm farm ecosystem

Mushroom compost, while nutrient-rich, harbors a hidden danger for worm farms: it attracts pests, particularly mites. These tiny invaders thrive in the organic matter and moisture retained by mushroom compost, creating an ideal breeding ground. Once established, mites can multiply rapidly, disrupting the delicate balance of your worm farm ecosystem. Their presence not only competes with worms for food but also stresses the worms, potentially leading to reduced reproduction and overall health decline.

Mites, though small, pose a significant threat to the well-being of your worm farm. They feed on organic matter, including worm eggs and even the worms themselves, directly impacting the farm's productivity. Additionally, their waste products can contribute to ammonia buildup, creating an unhealthy environment for worms and beneficial microorganisms. This can lead to a vicious cycle: stressed worms produce less castings, reducing the farm's output and potentially attracting even more pests.

To avoid this scenario, it's crucial to prioritize pest prevention. Avoid using mushroom compost altogether in your worm farm. Opt for alternative bedding materials like shredded cardboard, coconut coir, or aged manure, which provide suitable environments for worms without attracting unwanted guests. Regularly inspect your worm farm for signs of mite infestation, such as tiny white or red dots moving on the surface or a dusty appearance on the bedding. If mites are detected, take immediate action by removing affected areas, increasing ventilation, and introducing natural predators like predatory mites.

Remember, a healthy worm farm relies on a balanced ecosystem. By steering clear of mushroom compost and implementing preventive measures, you can create a thriving environment for your worms, free from the disruptive presence of pests like mites. This ensures a bountiful harvest of nutrient-rich castings and a sustainable, pest-free worm farming experience.

Do Mushrooms Use Glycolysis for Energy Production? Exploring Fungal Metabolism

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushroom compost often contains high levels of salts, heavy metals, and chemicals used in mushroom cultivation, which can be harmful or toxic to worms.

Yes, the residual chemicals, salts, and pH imbalances in mushroom compost can stress, injure, or kill worms, disrupting the worm farm ecosystem.

Yes, alternatives like shredded cardboard, coconut coir, peat moss, or aged manure are safer and more suitable for worm farms.

Even after washing or aging, mushroom compost may still retain harmful residues, so it’s best to avoid it entirely for worm farming.