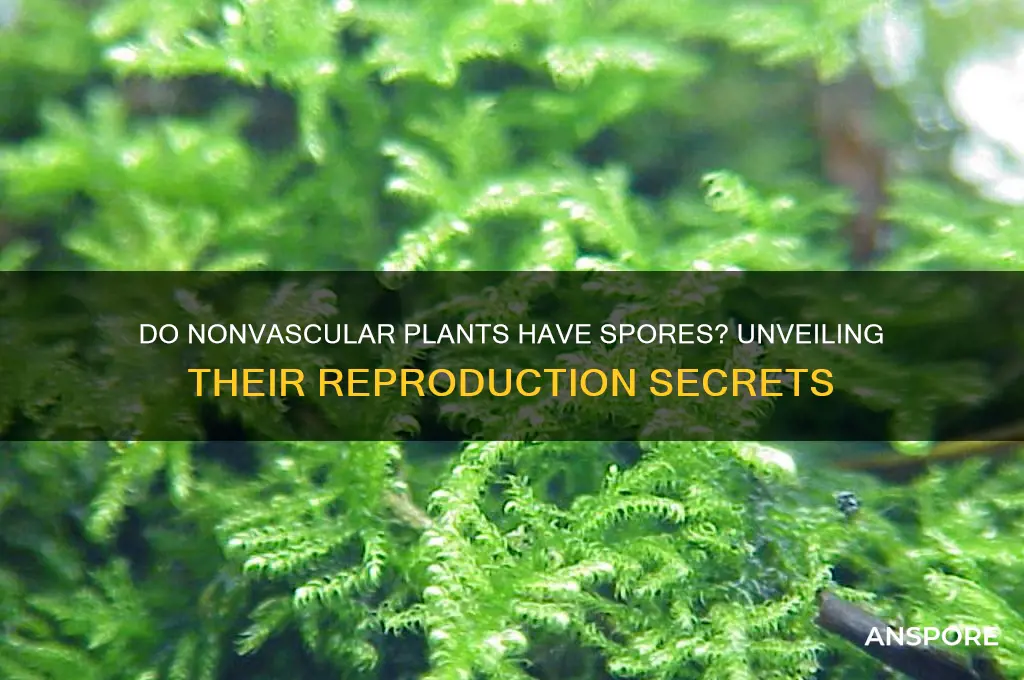

Nonvascular plants, such as mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, are a diverse group of primitive plants that lack specialized tissues for transporting water and nutrients. Unlike vascular plants, which have roots, stems, and leaves, nonvascular plants rely on simple structures to absorb moisture and nutrients directly from their environment. One of the most distinctive features of nonvascular plants is their reproductive strategy, which involves the production of spores rather than seeds. These spores are typically dispersed by wind or water and develop into new plants under favorable conditions, allowing nonvascular plants to thrive in damp, shaded habitats where they can remain consistently moist. This reliance on spores for reproduction is a key characteristic that distinguishes nonvascular plants from their more complex vascular counterparts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Nonvascular plants primarily reproduce via spores. |

| Spores | Yes, they produce spores for asexual reproduction. |

| Type of Spores | Haploid spores (single-celled and lightweight for dispersal). |

| Spore Dispersal | Dispersed by wind, water, or animals. |

| Life Cycle | Alternation of generations (sporophyte and gametophyte phases). |

| Dominant Phase | Gametophyte phase is dominant in nonvascular plants. |

| Examples | Mosses, liverworts, and hornworts. |

| Vascular Tissue | Absent (hence the name "nonvascular"). |

| Dependence on Water | Rely on water for reproduction and nutrient transport. |

| Habitat | Typically found in moist environments due to lack of vascular tissue. |

| Size | Generally small in size due to limited structural support. |

| Root-like Structures | Rhizoids (simple, non-vascular structures for anchorage and absorption). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Nonvascular plant reproduction methods

Nonvascular plants, such as mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, lack specialized tissues for transporting water and nutrients, yet they thrive in diverse environments through unique reproductive strategies. Central to their survival is the production and dispersal of spores, a method that ensures their persistence across generations. Unlike vascular plants, which rely on seeds, nonvascular plants depend on spores as their primary means of reproduction. These spores are lightweight, resilient, and capable of surviving harsh conditions, making them ideal for colonizing new habitats.

The reproductive process in nonvascular plants is a fascinating interplay of alternation of generations, where the plant alternates between a gametophyte (sexually reproducing) phase and a sporophyte (asexually reproducing) phase. The gametophyte, which is the dominant phase in nonvascular plants, produces gametes (sperm and eggs) through specialized structures. When sperm from the antheridia fertilize eggs in the archegonia, a sporophyte develops. This sporophyte then produces spores via meiosis in structures called sporangia. These spores, once dispersed, germinate into new gametophytes, completing the cycle.

One practical aspect of spore dispersal in nonvascular plants is their reliance on environmental factors such as wind, water, and even animals. For instance, moss spores are incredibly small and can travel long distances on air currents, allowing them to colonize distant or inaccessible areas. To encourage the growth of nonvascular plants in a garden or terrarium, ensure the environment is humid and shaded, as spores require moisture to germinate. Additionally, avoid overwatering, as standing water can suffocate the delicate gametophytes.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both nonvascular and vascular plants use spores, the former’s reliance on them is more pronounced due to their simpler structure. Vascular plants, with their seeds, have evolved more complex dispersal mechanisms, whereas nonvascular plants depend on sheer numbers and environmental adaptability. For enthusiasts cultivating nonvascular plants, collecting spores from mature sporophytes and sprinkling them onto a damp, nutrient-rich substrate can initiate growth. Patience is key, as spore germination and gametophyte development can take weeks.

In conclusion, nonvascular plants’ reproductive methods are a testament to their evolutionary success. By harnessing spores, they overcome their structural limitations and thrive in environments where more complex plants might struggle. Understanding these methods not only deepens appreciation for their biology but also provides practical insights for cultivation and conservation efforts. Whether in a laboratory, garden, or natural habitat, the study of nonvascular plant reproduction offers valuable lessons in resilience and adaptability.

Are Fungal Spores Dangerous? Unveiling Health Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Role of spores in nonvascular plants

Nonvascular plants, such as mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, rely on spores as their primary means of reproduction and dispersal. Unlike vascular plants, which have specialized tissues for water and nutrient transport, nonvascular plants lack these structures, making spores essential for their survival. Spores are lightweight, single-celled reproductive units that can be carried by wind or water to new locations, allowing nonvascular plants to colonize diverse environments, from damp forests to rocky outcrops. This adaptability is crucial for their persistence in habitats where seed-based reproduction is impractical.

The role of spores in nonvascular plants extends beyond mere reproduction; they are also a survival mechanism. Spores are highly resistant to harsh conditions, such as drought, extreme temperatures, and nutrient scarcity. This dormancy enables nonvascular plants to endure unfavorable periods, germinating only when conditions improve. For example, moss spores can remain viable in soil for years, waiting for the right combination of moisture and light to trigger growth. This resilience is a key factor in the success of nonvascular plants in ecosystems where stability is rare.

To understand the practical significance of spores, consider their role in the life cycle of a liverwort. After the gametophyte (the dominant phase) produces spores in specialized structures called sporangia, these spores are released into the environment. Each spore develops into a new gametophyte, ensuring the continuation of the species. This process bypasses the need for seeds, which require more resources and protection. For gardeners or ecologists aiming to cultivate nonvascular plants, collecting and dispersing spores in moist, shaded areas can effectively establish new colonies, particularly in restoration projects or green roofs.

Comparatively, spores in nonvascular plants differ from those in ferns or fungi in their function and structure. While fern spores are part of an alternation of generations involving a dominant sporophyte, nonvascular plant spores develop directly into gametophytes, simplifying their life cycle. This distinction highlights the evolutionary efficiency of nonvascular plants, which prioritize rapid colonization over complex development. By studying these differences, researchers gain insights into plant evolution and the strategies organisms employ to thrive in challenging environments.

In conclusion, spores are indispensable to nonvascular plants, serving as both reproductive units and survival tools. Their lightweight nature, resistance to adversity, and ability to germinate under optimal conditions make them a cornerstone of nonvascular plant ecology. Whether in scientific research, conservation efforts, or horticulture, understanding the role of spores provides practical applications for sustaining these ancient and resilient organisms in modern landscapes.

Are Mold Spores Carcinogens? Uncovering the Health Risks and Facts

You may want to see also

Alternation of generations in nonvascular plants

Nonvascular plants, such as mosses and liverworts, exhibit a fascinating life cycle known as alternation of generations, where two distinct phases—the gametophyte and sporophyte—alternate in a continuous reproductive dance. Unlike vascular plants, where the sporophyte dominates, nonvascular plants are gametophyte-dominant, meaning the green, photosynthetic structures we commonly see are the gametophytes. These gametophytes produce gametes (sperm and eggs) that, upon fertilization, give rise to the sporophyte generation. This sporophyte, often smaller and dependent on the gametophyte, produces spores that develop into new gametophytes, completing the cycle.

To understand this process, consider the life cycle of a moss. The gametophyte phase begins with a spore germinating into a protonema, a thread-like structure that eventually develops into the leafy gametophyte. This gametophyte is dioicous, meaning male and female reproductive organs are on separate plants. When water is present, sperm from the male gametophyte swim to the female gametophyte to fertilize the egg, forming a zygote. This zygote grows into the sporophyte, which remains attached to and nourished by the gametophyte. The sporophyte then produces a capsule where spores are generated through meiosis, and when released, these spores initiate the next generation of gametophytes.

A critical aspect of alternation of generations in nonvascular plants is the dependency of the sporophyte on the gametophyte. Unlike vascular plants, where the sporophyte is independent and often long-lived, nonvascular sporophytes are short-lived and rely on the gametophyte for water, nutrients, and structural support. This dependency highlights the evolutionary transition from simpler, nonvascular plants to more complex vascular plants, where the sporophyte becomes dominant. For gardeners or enthusiasts cultivating mosses, ensuring consistent moisture is key, as water is essential for sperm mobility during fertilization and sporophyte development.

Comparatively, alternation of generations in nonvascular plants differs from that in vascular plants in both structure and dominance. In ferns, for example, the sporophyte is the prominent, free-living generation, while the gametophyte (prothallus) is small and transient. In contrast, nonvascular plants prioritize the gametophyte, which is the more visible and enduring phase. This distinction underscores the evolutionary adaptations of nonvascular plants to their typically moist, terrestrial habitats, where water availability supports gametophyte survival and reproduction.

Practically, understanding alternation of generations in nonvascular plants can enhance conservation efforts and horticultural practices. For instance, when propagating mosses, knowing that spores develop into gametophytes allows for controlled environments with high humidity and indirect light to encourage growth. Additionally, recognizing the sporophyte’s dependence on the gametophyte emphasizes the importance of preserving entire ecosystems rather than individual plants, as both generations are interdependent. This knowledge not only deepens appreciation for these ancient organisms but also informs strategies for their cultivation and protection.

Where to Legally Obtain Psilocybin Spores for Research and Cultivation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Types of spores produced by nonvascular plants

Nonvascular plants, such as mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, rely on spores for reproduction, a strategy that ensures their survival in diverse environments. These plants produce two primary types of spores: haploid spores and diploid spores, though the latter is less common. Haploid spores are the most prevalent and are produced through the process of meiosis in the sporophyte generation. These spores develop into the gametophyte generation, which is the dominant phase in the life cycle of nonvascular plants. Understanding the types of spores these plants produce is crucial for appreciating their reproductive strategies and ecological roles.

One notable type of spore produced by nonvascular plants is the elaters, found in hornworts. Elaters are specialized, spiral-shaped cells that aid in spore dispersal. When dry, they coil tightly, and when exposed to moisture, they uncoil, propelling the spores away from the parent plant. This mechanism enhances the chances of spores reaching new habitats, a critical adaptation for plants lacking vascular tissue to transport water and nutrients. Elaters are a fascinating example of how nonvascular plants have evolved unique structures to overcome their limitations.

Mosses, another group of nonvascular plants, produce ordinary spores that are dispersed by wind. These spores are typically housed in a capsule called a sporangium, which dries out and splits open to release the spores. Unlike hornworts, mosses lack elaters, relying instead on the physical structure of the sporangium and environmental factors like wind currents for dispersal. The simplicity of this mechanism highlights the efficiency of mosses in colonizing new areas despite their lack of complex dispersal structures.

Liverworts exhibit a more diverse range of spore types, including smooth spores and ornamented spores. Smooth spores are spherical and lack surface structures, while ornamented spores have intricate patterns or ridges. These variations influence how spores interact with their environment, such as adhesion to surfaces or resistance to desiccation. For example, ornamented spores in some liverwort species may enhance their ability to survive in dry conditions, a critical advantage in arid habitats.

Practical observation of these spores can be achieved through simple techniques. To examine spores under a microscope, collect a mature sporangium from a nonvascular plant, place it on a slide, and gently tap it to release the spores. For elaters, observe their coiling and uncoiling behavior by exposing them to alternating dry and moist conditions. Such hands-on exploration not only deepens understanding but also highlights the ingenuity of nonvascular plants in adapting to their environments through diverse spore types.

Can Corynebacterium Form Spores? Unraveling the Bacterial Survival Mystery

You may want to see also

Environmental adaptations of nonvascular plant spores

Nonvascular plants, such as mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, rely on spores for reproduction and survival in diverse environments. These spores are not just miniature replicas of the parent plant; they are highly adapted structures designed to withstand harsh conditions and disperse efficiently. Understanding their environmental adaptations reveals how nonvascular plants thrive in habitats ranging from arid deserts to dense forests.

One key adaptation is the protective outer layer of spores, known as the exine. This layer is composed of sporopollenin, a durable biopolymer resistant to desiccation, UV radiation, and extreme temperatures. For example, moss spores can remain viable in soil for decades, waiting for optimal moisture and light conditions to germinate. This resilience allows nonvascular plants to colonize unstable environments, such as rock surfaces or disturbed soils, where other plants struggle to survive.

Another critical adaptation is dormancy, a state in which spores suspend metabolic activity until conditions are favorable. This mechanism is particularly vital in unpredictable climates, such as temperate regions with seasonal fluctuations. Spores of liverworts, for instance, can enter dormancy during dry periods and revive rapidly after rainfall. This ability ensures the long-term survival of the species, even in habitats with limited water availability.

Dispersal mechanisms also play a pivotal role in spore adaptation. Nonvascular plant spores are lightweight and often equipped with structures like elaters (in hornworts) or air pockets, enabling wind dispersal over long distances. This adaptation allows them to reach new habitats efficiently, increasing their chances of finding suitable environments for growth. For practical application, gardeners can mimic natural dispersal by scattering moss spores on damp, shaded surfaces to encourage colonization.

Finally, spores exhibit phenotypic plasticity, the ability to alter their development based on environmental cues. For example, spores exposed to high humidity may germinate quickly, while those in drier conditions may delay germination until moisture levels rise. This flexibility ensures that spores only invest energy in growth when survival is likely, a strategy particularly beneficial in resource-limited ecosystems.

In summary, the environmental adaptations of nonvascular plant spores—protective layers, dormancy, dispersal mechanisms, and phenotypic plasticity—enable these plants to thrive in challenging habitats. By studying these adaptations, we gain insights into the resilience of nonvascular plants and practical strategies for their cultivation and conservation.

Do Albino Mushrooms Drop Spores? Unveiling the Truth Behind Albino Strains

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, nonvascular plants, such as mosses and liverworts, reproduce via spores as part of their life cycle.

Nonvascular plants produce spores in structures called sporangia, which develop on the gametophyte generation during their alternation of generations life cycle.

Nonvascular plants rely on spores because they lack true roots, stems, and leaves, making them dependent on water for reproduction and dispersal, which spores facilitate effectively.