Plants exhibit a unique life cycle known as alternation of generations, where they alternate between a haploid and a diploid phase. In this cycle, the question of whether plants produce haploid or diploid spores depends on the specific stage of their life cycle. During the sporophyte generation, which is the diploid phase, plants produce haploid spores through meiosis. These spores then develop into the gametophyte generation, which is haploid. The gametophytes, in turn, produce gametes (sperm and egg cells) that fuse during fertilization to form a new diploid sporophyte. Therefore, plants produce haploid spores during their sporophyte phase, ensuring the continuation of their life cycle.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Spores Produced by Plants | Plants produce both haploid and diploid spores, depending on the life cycle stage and the type of plant. |

| Haploid Spores | Produced during the sporophyte phase in the life cycle of plants (e.g., pollen grains in seed plants, spores in ferns and mosses). These spores develop into gametophytes. |

| Diploid Spores | Not typically produced in most plants. However, some algae and certain plant-like organisms (e.g., some fungi) may produce diploid spores under specific conditions. |

| Life Cycle Dominance | In vascular plants (ferns, gymnosperms, angiosperms), the sporophyte (diploid) generation is dominant, while the gametophyte (haploid) generation is reduced. |

| Role of Haploid Spores | Haploid spores germinate to form gametophytes, which produce gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction. |

| Role of Diploid Spores (if present) | In organisms that produce diploid spores, they may directly develop into new individuals without a haploid phase, bypassing the alternation of generations. |

| Alternation of Generations | Plants exhibit alternation of generations, cycling between haploid (gametophyte) and diploid (sporophyte) phases. Haploid spores are key to this process. |

| Examples of Haploid Spores | Fern spores, moss spores, pollen grains in flowering plants. |

| Examples of Diploid Spores | Rare in true plants; more common in algae (e.g., zygotes in some green algae) and certain fungi. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporophyte vs Gametophyte Generations: Alternation of generations explains haploid and diploid phases in plant life cycles

- Haploid Spores Formation: Meiosis in sporophyte produces haploid spores in plants like ferns and mosses

- Diploid Spores in Plants: Some algae and fungi produce diploid spores, differing from typical plant cycles

- Role of Spores in Reproduction: Spores germinate into gametophytes, ensuring genetic diversity in plant reproduction

- Exceptions in Plant Spores: Certain plants, like liverworts, show unique haploid-diploid spore variations

Sporophyte vs Gametophyte Generations: Alternation of generations explains haploid and diploid phases in plant life cycles

Plants exhibit a unique reproductive strategy known as alternation of generations, where their life cycle alternates between two distinct phases: the sporophyte and gametophyte generations. This process is fundamental to understanding whether plants produce haploid or diploid spores. The sporophyte generation is the dominant, visible phase in most plants, characterized by its diploid cells (2n chromosomes). It produces spores through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid spores (n chromosomes). These spores then develop into the gametophyte generation, which is typically smaller and less conspicuous.

Consider the life cycle of a fern as an illustrative example. The large, leafy fern plant you see is the sporophyte generation. On the underside of its fronds, it produces sporangia, structures that release haploid spores. These spores germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes (prothalli), which are often hidden in soil or damp environments. The gametophyte generation is haploid and produces gametes (sperm and eggs) through mitosis. When fertilization occurs, the resulting zygote develops into a new sporophyte, completing the cycle. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in plant populations.

From an analytical perspective, the sporophyte and gametophyte generations serve distinct ecological roles. The sporophyte, being diploid, is more robust and better suited for long-term survival in diverse environments. It invests energy in growth and spore production, relying on its size and structure to disperse spores effectively. In contrast, the gametophyte, being haploid, is often short-lived and dependent on moist conditions for survival. Its primary function is to produce gametes, ensuring the continuation of the species through sexual reproduction. This division of labor highlights the evolutionary advantages of alternation of generations.

To understand the practical implications, consider horticulture and agriculture. In seed-producing plants (angiosperms and gymnosperms), the sporophyte generation is the cultivated plant, while the gametophyte is reduced to a few cells within the flower or cone. For example, in corn, the tassel (male flower) and ear (female flower) contain the gametophytes. Farmers manipulate this cycle by controlling pollination to improve crop yield. Similarly, in horticulture, understanding alternation of generations helps breeders develop plants with desirable traits, such as disease resistance or enhanced productivity.

In conclusion, the alternation of generations in plants is a sophisticated mechanism that balances haploid and diploid phases. The sporophyte generation, with its diploid cells, produces haploid spores that develop into the gametophyte generation. This cycle ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, with each phase serving distinct ecological and reproductive roles. Whether in natural ecosystems or agricultural settings, recognizing the interplay between sporophyte and gametophyte generations provides valuable insights into plant biology and practical applications in plant cultivation.

Understanding Spores: Nature's Ingenious Method for Reproduction and Survival

You may want to see also

Haploid Spores Formation: Meiosis in sporophyte produces haploid spores in plants like ferns and mosses

Plants like ferns and mosses exhibit a fascinating reproductive strategy centered on the production of haploid spores through meiosis in the sporophyte generation. This process is a cornerstone of their life cycle, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. Meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, occurs within the sporophyte—the diploid phase of these plants. The resulting spores are haploid, carrying a single set of chromosomes, and are dispersed to develop into the gametophyte generation. This alternation of generations is a defining feature of non-seed plants, showcasing the intricate balance between asexual and sexual reproduction.

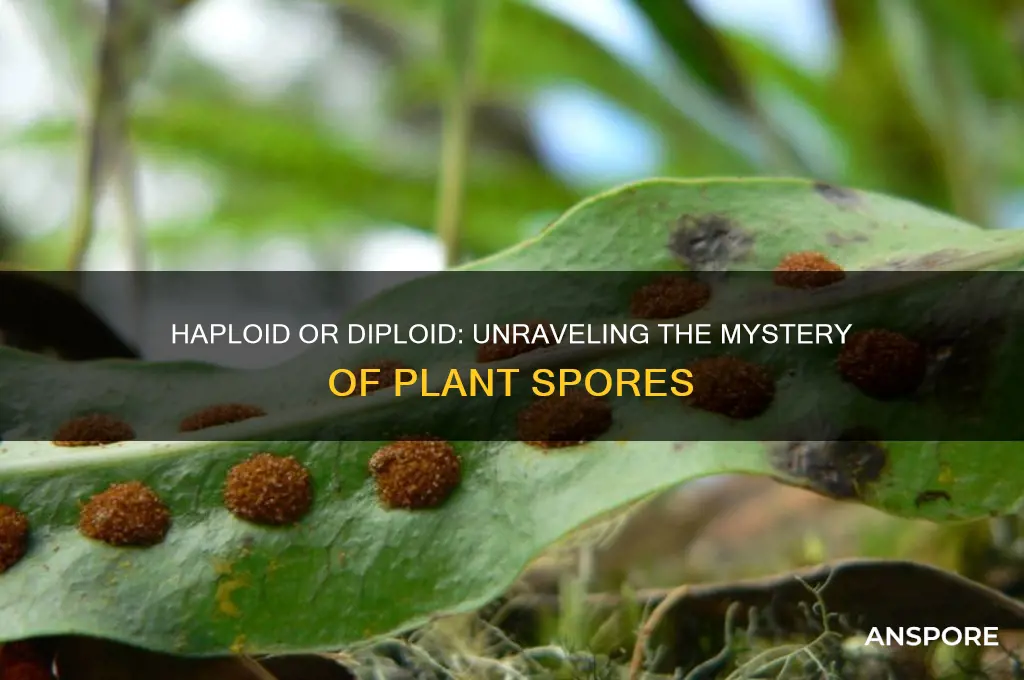

Consider the fern life cycle as a practical example. The sporophyte, the familiar fern plant we often see, produces spore cases (sporangia) on the undersides of its leaves. Within these sporangia, meiosis generates haploid spores. When released, these spores germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes, which are often no larger than a thumbnail. These gametophytes are short-lived but crucial, producing gametes (sperm and eggs) that fuse to form a new sporophyte. This cycle highlights the efficiency of haploid spore formation, allowing ferns to thrive in diverse environments, from shady forests to rocky crevices.

Analyzing the role of meiosis in spore formation reveals its significance in maintaining genetic diversity. Unlike mitosis, which produces genetically identical cells, meiosis introduces genetic recombination through crossing over and independent assortment. This diversity is vital for plants like mosses, which often inhabit harsh, unpredictable environments. For instance, a moss sporophyte growing in a damp, shaded area may produce spores with varied traits, increasing the likelihood that some will survive in drier or brighter conditions. This adaptability is a direct result of the haploid spore formation process, ensuring the species’ resilience over generations.

For enthusiasts or educators looking to observe this process, here’s a practical tip: collect mature fern fronds with visible spore cases (brown dots on the underside) and place them on a sheet of white paper. Over time, the sporangia will release spores, creating a pattern that can be examined under a magnifying glass or microscope. This simple experiment not only illustrates haploid spore formation but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the complexity of plant reproduction. By understanding this mechanism, we gain insight into the evolutionary success of non-seed plants and their ability to colonize diverse habitats.

In conclusion, the formation of haploid spores through meiosis in the sporophyte is a remarkable adaptation in plants like ferns and mosses. It ensures genetic diversity, supports survival in varying environments, and exemplifies the elegance of alternation of generations. Whether through analytical study, hands-on observation, or comparative analysis, exploring this process enriches our understanding of plant biology and its broader ecological implications.

Mold Spores and Eye Health: Uncovering Potential Risks and Symptoms

You may want to see also

Diploid Spores in Plants: Some algae and fungi produce diploid spores, differing from typical plant cycles

Plants typically follow a life cycle where haploid spores are produced, but this isn't the case for all organisms traditionally grouped with plants. Some algae and fungi, often studied alongside plant biology, deviate from this norm by producing diploid spores. This distinction is crucial for understanding the diversity of reproductive strategies in the biological world. For instance, certain species of red algae, like *Porphyra*, exhibit a life cycle dominated by the diploid phase, releasing diploid spores that grow directly into the mature form. This contrasts sharply with the haploid-dominant cycles seen in most vascular plants, where spores develop into gametophytes before fertilization.

To grasp the significance of diploid spores, consider the evolutionary advantages they offer. In environments with stable conditions, maintaining a diploid state can reduce the energy and time required for meiosis and gamete production. For example, some fungi, such as *Aspergillus*, produce diploid spores (ascospores) that germinate rapidly, allowing for quick colonization of new habitats. This strategy ensures survival in competitive ecosystems where speed of reproduction is key. However, this approach also limits genetic diversity, which can be a drawback in changing environments.

If you're studying plant biology or working in fields like agriculture or biotechnology, understanding these variations is essential. For instance, knowing that certain algae produce diploid spores can inform strategies for cultivating seaweed or developing biofuels. Similarly, in mycology, recognizing diploid spore production in fungi can aid in controlling pathogens or optimizing mushroom cultivation. Practical tips include observing spore morphology under a microscope to identify ploidy levels and tracking environmental conditions that favor diploid spore formation, such as consistent temperature and nutrient availability.

Comparing these atypical cycles to the standard plant life cycle highlights the adaptability of reproductive strategies. While most plants prioritize genetic diversity through haploid spores, organisms like algae and fungi often prioritize efficiency and stability. This comparison underscores the importance of context in biology: what works for one species may not for another. For educators or researchers, incorporating these examples into lessons or experiments can provide a more comprehensive view of plant and fungal biology, encouraging students to think critically about evolutionary trade-offs.

In conclusion, the production of diploid spores in some algae and fungi challenges the assumption that all "plant-like" organisms follow a haploid-dominant cycle. This variation offers insights into evolutionary strategies and practical applications in fields ranging from agriculture to biotechnology. By studying these exceptions, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and diversity of life cycles in the natural world. Whether you're a student, researcher, or practitioner, recognizing these differences can enhance your understanding and approach to biological systems.

Mold Spores in Flour: Can Fermentation Eliminate Them?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of Spores in Reproduction: Spores germinate into gametophytes, ensuring genetic diversity in plant reproduction

Plants, unlike animals, rely on spores as a critical component of their reproductive cycle. These spores are haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes, a characteristic that plays a pivotal role in the genetic diversity of plant species. This haploid nature is a fundamental distinction from diploid spores, which are not typically found in the plant kingdom. The process begins with the production of spores within specialized structures like sporangia, where they are formed through meiosis, ensuring each spore carries a unique genetic makeup.

The germination of these haploid spores into gametophytes marks a crucial phase in plant reproduction. Gametophytes are the sexual phase of the plant life cycle, producing gametes (sperm and eggs) that will eventually combine to form a diploid zygote. This transition from spore to gametophyte is not merely a growth process but a strategic mechanism to enhance genetic variability. For instance, in ferns, spores develop into small, heart-shaped gametophytes that can exist independently for a short period, allowing for the exchange of genetic material through fertilization.

Genetic diversity is further amplified by the fact that spores can disperse over vast distances, carried by wind, water, or animals. This dispersal mechanism ensures that plants can colonize new areas and adapt to diverse environments. For example, moss spores, being lightweight and numerous, can travel significant distances, enabling mosses to thrive in various habitats, from arctic tundras to tropical rainforests. This adaptability is a direct result of the haploid nature of spores, which facilitates rapid evolution and survival in changing conditions.

In agricultural and horticultural practices, understanding the role of spores can be immensely beneficial. For instance, seed companies often focus on developing varieties that produce robust spores, ensuring higher germination rates and healthier plants. Gardeners can also utilize this knowledge by creating environments conducive to spore germination, such as maintaining moisture levels and providing adequate light. By fostering the growth of gametophytes, gardeners can encourage the development of stronger, more resilient plants.

The role of spores in plant reproduction is a testament to the ingenuity of nature’s design. By producing haploid spores that germinate into gametophytes, plants ensure not only the continuation of their species but also the introduction of genetic diversity. This diversity is crucial for the long-term survival of plant populations, enabling them to withstand diseases, pests, and environmental changes. Whether in the wild or in cultivated settings, the humble spore remains a cornerstone of plant life, bridging generations and fostering adaptability.

Are Spores Male or Female? Unraveling the Mystery of Fungal Reproduction

You may want to see also

Exceptions in Plant Spores: Certain plants, like liverworts, show unique haploid-diploid spore variations

Plants typically produce haploid spores as part of their life cycle, a fundamental aspect of their alternation of generations. However, certain plants, such as liverworts, defy this norm by exhibiting unique haploid-diploid spore variations. Liverworts, belonging to the division Marchantiophyta, showcase a distinct reproductive strategy where both haploid and diploid phases are prominent, but with intriguing exceptions. Unlike most plants, liverworts produce spores that develop into free-living gametophytes, which are haploid, but their sporophytes (spore-producing structures) remain dependent on the gametophyte and are diploid. This dual nature highlights a fascinating departure from the standard plant life cycle.

To understand these exceptions, consider the reproductive process of liverworts. After fertilization, the diploid sporophyte grows on the haploid gametophyte, forming a sporangium where spores are produced via meiosis, resulting in haploid spores. However, some liverwort species, like *Marchantia*, produce gemmae—small, asexual, multicellular structures that are genetically identical to the parent plant. These gemmae are neither strictly haploid nor diploid spores but serve as a unique reproductive adaptation. This variation underscores the evolutionary flexibility of liverworts in adapting to diverse environments.

Analyzing these exceptions reveals their ecological significance. Liverworts often thrive in moist, shaded habitats where traditional spore dispersal might be less effective. The production of gemmae allows for rapid, localized colonization, ensuring survival in stable but resource-limited environments. This strategy contrasts with the long-distance dispersal of haploid spores seen in other plants, which is advantageous in dynamic ecosystems. Thus, liverworts’ spore variations are not just biological curiosities but adaptive responses to specific ecological pressures.

For enthusiasts or researchers studying these exceptions, practical tips include observing liverwort habitats during their reproductive phases, typically in spring or early summer. Collecting gemmae for cultivation can provide insights into their asexual reproduction, while examining sporangia under a microscope reveals the haploid spores. Documenting these variations across species can contribute to a broader understanding of plant reproductive diversity. By focusing on these exceptions, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and ingenuity of plant life cycles.

Are Botulism Spores Dangerous? Understanding Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Plants produce haploid spores. These spores are formed through meiosis, which reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in a single set of chromosomes.

Haploid spores develop into gametophytes, which are the structures that produce gametes (sperm and egg cells). These gametes then fuse during fertilization to form a diploid zygote, which grows into a new plant.

No, plants do not produce diploid spores. However, some fungi and algae produce diploid spores as part of their life cycles, but this is not the case for plants.

Haploid spores have a single set of chromosomes (n), while diploid cells, such as those in the sporophyte generation of plants, have two sets of chromosomes (2n). This difference is fundamental to the alternation of generations in plant life cycles.