Pteridophytes, a group of vascular plants that includes ferns, horsetails, and lycophytes, are characterized by their unique reproductive structures. One of the most distinctive features of these plants is their method of reproduction through spores, which are typically produced in specialized structures called sporangia. However, the question of whether pteridophytes have spore capsules is a nuanced one. While some pteridophytes, such as certain lycophytes, do produce spore-bearing structures that can be described as capsules, the majority of ferns and horsetails release their spores from open sporangia, often clustered into structures like sori. Therefore, while not all pteridophytes have spore capsules in the strictest sense, their reproductive mechanisms are adapted to efficiently disperse spores, ensuring the continuation of their species.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Capsules | Yes, pteridophytes (ferns and fern allies) produce spore capsules called sporangia. |

| Location of Sporangia | Typically found on the underside of leaves (fronds) or on specialized structures like sori. |

| Structure of Sporangia | Sporangia are sac-like structures that contain and disperse spores. |

| Type of Spores | Produce haploid spores through alternation of generations. |

| Function of Spores | Spores are dispersed for reproduction and develop into gametophytes. |

| Protection of Spores | Sporangia provide protection to spores until they are ready for dispersal. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are often dispersed by wind or water. |

| Examples of Pteridophytes | Ferns, horsetails, and clubmosses. |

| Life Cycle | Exhibit an alternation of generations with both sporophyte and gametophyte phases. |

| Vascular Tissue | Possess vascular tissue (xylem and phloem) for water and nutrient transport. |

| Reproduction | Reproduce via spores (asexual) and gametophytes (sexual). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Production Mechanisms: How pteridophytes produce and disperse spores without capsules

- Structure of Sporangia: Differences between sporangia and spore capsules in plant groups

- Evolutionary Adaptations: Why pteridophytes lack spore capsules compared to other plants

- Role of Indusia: Protective structures in pteridophytes instead of capsules

- Comparison with Bryophytes: Contrasting spore dispersal methods in bryophytes and pteridophytes

Spore Production Mechanisms: How pteridophytes produce and disperse spores without capsules

Pteridophytes, a group of vascular plants including ferns, horsetails, and lycophytes, produce and disperse spores without the use of capsules, relying instead on specialized structures called sporangia. These sporangia are typically located on the undersides of leaves or on modified structures like fern fiddleheads. Unlike spore capsules found in some other plant groups, sporangia in pteridophytes are open structures that release spores directly into the environment. This mechanism allows for efficient dispersal, particularly in humid environments where spores can be carried by air currents or water.

The process of spore production in pteridophytes begins with the development of sporophylls, leaves modified to bear sporangia. In ferns, these sporophylls are often clustered into structures called sori, which are protected by a thin, membrane-like covering called the indusium. As the sporangia mature, they undergo a series of cellular changes, including the formation of a ring-like structure called the annulus. This annulus is crucial for spore release, as it responds to environmental cues like humidity by changing shape, causing the sporangium to open and eject spores with force. This mechanism ensures that spores are dispersed at optimal times, increasing the likelihood of successful germination.

Dispersal of spores in pteridophytes is highly dependent on environmental conditions. For example, in dry environments, spores may be released in small bursts to conserve moisture, while in humid conditions, larger quantities are released to take advantage of air currents. The lightweight, single-celled nature of pteridophyte spores also aids in their dispersal, allowing them to travel significant distances. Once released, spores can remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for favorable conditions to germinate into gametophytes, the next stage in the pteridophyte life cycle.

Practical observation of this process can be done by examining mature fern fronds under a magnifying glass. Look for clusters of brown or yellow dots (sori) on the undersides of leaves, which indicate the presence of sporangia. Gently touching these areas may cause spores to be released as a fine, dusty powder. For educational purposes, collecting spores for germination experiments can be done by placing a mature frond on a sheet of paper and allowing the spores to naturally drop. These spores can then be sown on a moist substrate, such as a mixture of peat and sand, and kept in a humid environment to observe gametophyte development.

In comparison to plants with spore capsules, pteridophytes’ open sporangia represent a trade-off between protection and dispersal efficiency. While capsules provide a more controlled release and protection from harsh conditions, the open nature of sporangia allows for rapid and widespread dispersal. This adaptation is particularly advantageous in the diverse habitats pteridophytes occupy, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands. Understanding these mechanisms not only highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of pteridophytes but also provides insights into plant reproduction strategies in different ecological contexts.

Boiling and Botulism: Can Heat Kill Dangerous Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Structure of Sporangia: Differences between sporangia and spore capsules in plant groups

Pteridophytes, such as ferns and horsetails, produce spores within structures called sporangia, not spore capsules. This distinction is crucial for understanding their reproductive biology. Sporangia are typically found on the undersides of fern fronds or on specialized structures like the cones of horsetails. These sac-like structures develop from a single cell and undergo mitosis to produce numerous spores. In contrast, spore capsules, commonly found in non-vascular plants like mosses and liverworts, are more complex, often protected by a multicellular jacket and opening via an elaborate mechanism.

To illustrate the difference, consider the lifecycle of a fern. Sporangia cluster into structures called sori, often protected by a thin membrane called the indusium. When mature, the sporangia release spores through a ring-like structure called the annulus, which responds to humidity changes. This mechanism is efficient but lacks the protective layers seen in spore capsules. In mosses, spore capsules (sporangia) are elevated on a seta, a stalk-like structure, and have a lid (operculum) that detaches to release spores. This design reflects the need for protection in drier environments where mosses often grow.

The structural simplicity of sporangia in pteridophytes aligns with their vascularized nature, allowing for direct transport of water and nutrients to the reproductive organs. Spore capsules, on the other hand, are an adaptation of non-vascular plants to survive desiccation and disperse spores effectively. For instance, the peristome teeth in moss spore capsules control spore release in response to humidity, a feature absent in pteridophyte sporangia. This comparison highlights how plant groups evolve distinct reproductive structures based on their ecological niches.

Practical observation can deepen understanding of these differences. To examine sporangia, collect a mature fern frond and use a magnifying glass to locate sori. Gently pressing the frond onto paper will release spores, visible as fine dust. For spore capsules, gather a moss plant with mature sporophytes and observe the capsule’s structure under a microscope. Note the operculum and peristome, which are absent in pteridophyte sporangia. Such hands-on exploration reinforces the structural and functional disparities between these reproductive organs.

In summary, while both sporangia and spore capsules serve to produce and disperse spores, their structures reflect the evolutionary adaptations of their respective plant groups. Pteridophytes rely on simple, vascularized sporangia, whereas non-vascular plants develop complex spore capsules to cope with harsher environments. Recognizing these differences not only aids in plant identification but also underscores the diversity of reproductive strategies in the plant kingdom.

Mold Spores vs. Bacteria: Understanding the Key Differences and Similarities

You may want to see also

Evolutionary Adaptations: Why pteridophytes lack spore capsules compared to other plants

Pteridophytes, a group of vascular plants including ferns and their relatives, notably lack spore capsules—a feature common in other plant groups like mosses and liverworts. This absence is not an oversight of evolution but a strategic adaptation shaped by their life cycle and environmental interactions. Unlike bryophytes, which rely on spore capsules for protection and dispersal, pteridophytes have evolved alternative mechanisms to ensure reproductive success. Their spores are produced in clusters on the undersides of leaves, exposed directly to the environment. This design reflects a trade-off: while it lacks the physical protection of a capsule, it maximizes dispersal efficiency through wind and water, critical for plants often found in shaded, humid habitats.

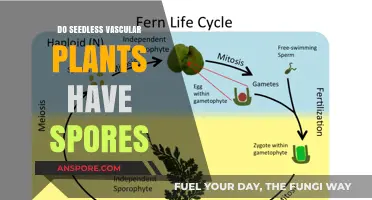

Consider the life cycle of pteridophytes to understand this adaptation. These plants alternate between a sporophyte (spore-producing) and gametophyte (gamete-producing) phase, with the gametophyte being a small, free-living organism. The absence of spore capsules aligns with the need for rapid spore release to colonize new areas quickly. Enclosing spores in a capsule would introduce delays in dispersal, a disadvantage in competitive ecosystems. Instead, the open structure of pteridophyte sporangia allows for immediate release, ensuring spores can travel far and wide with minimal obstruction. This strategy is particularly effective in their typical environments, such as forest floors, where wind currents and moisture facilitate spore movement.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the lack of spore capsules in pteridophytes highlights a shift in reproductive priorities. While bryophytes prioritize spore protection in their often harsh, exposed habitats, pteridophytes prioritize dispersal in more stable, shaded environments. This difference underscores the principle of adaptation to specific ecological niches. Pteridophytes’ success lies in their ability to produce large quantities of spores, compensating for the lack of physical protection with sheer numbers. For instance, a single fern frond can release thousands of spores, increasing the likelihood of successful germination in suitable locations.

Practical observations of pteridophytes in their natural habitats further illustrate this adaptation. In tropical rainforests, ferns thrive in understory layers where light is limited but humidity is high. Their exposed sporangia take advantage of the constant airflow and moisture, ensuring spores are dispersed efficiently. In contrast, spore capsules would be less effective in such conditions, as they require specific mechanisms (e.g., drying or mechanical triggers) to release spores. Pteridophytes’ approach is simpler and more aligned with their environment, demonstrating how evolutionary adaptations are finely tuned to ecological demands.

In conclusion, the absence of spore capsules in pteridophytes is not a deficiency but a refined evolutionary strategy. By forgoing the protective structures seen in other plants, they optimize spore dispersal—a critical advantage in their habitats. This adaptation reflects a broader theme in biology: organisms evolve traits not in isolation but in response to their environment. For gardeners or botanists cultivating pteridophytes, understanding this adaptation can inform care practices, such as ensuring adequate airflow and humidity to mimic natural dispersal conditions. In the study of plant evolution, pteridophytes serve as a prime example of how form follows function, shaped by the relentless pressures of survival and reproduction.

Are Shroom Spores Psychoactive? Unraveling the Truth Behind the Myth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of Indusia: Protective structures in pteridophytes instead of capsules

Pteridophytes, a group of vascular plants including ferns and their relatives, do not produce spore capsules like some other plant groups. Instead, they rely on a unique protective structure called the indusium to safeguard their spores. This thin, delicate membrane covers the sporangia, the structures where spores are produced, and plays a critical role in spore development and dispersal. Understanding the function of indusia offers insight into the evolutionary adaptations of pteridophytes and their survival strategies.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern. After fertilization, the developing spores are vulnerable to environmental stressors such as desiccation, predation, and physical damage. The indusium acts as a barrier, shielding the spores during their maturation. Unlike the rigid spore capsules of mosses or liverworts, the indusium is flexible and often translucent, allowing for gas exchange while providing protection. This balance between shielding and permeability is essential for spore viability, ensuring that the next generation of plants can thrive.

From a comparative perspective, the indusium serves a purpose similar to that of spore capsules but with distinct advantages. Capsules, while robust, often require mechanical mechanisms for spore release, such as explosive dehiscence. In contrast, the indusium typically withers or opens gradually as the spores mature, allowing for a more controlled and energy-efficient dispersal process. This adaptation highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of pteridophytes, which have optimized their reproductive structures to suit their ecological niches.

For enthusiasts or researchers studying pteridophytes, observing the indusium can provide valuable insights into the plant’s reproductive health. Look for its presence on the underside of fern fronds, often as a thin, papery covering over the sori (clusters of sporangia). Gently lifting the indusium with a fine tool can reveal the sporangia beneath, though caution is advised to avoid damaging the delicate structure. Documenting its shape, color, and condition can aid in species identification and understanding its role in spore protection.

In practical terms, the indusium’s protective function has implications for conservation efforts. Habitat disruption, pollution, or climate change can compromise its integrity, affecting spore survival. For instance, increased humidity levels may cause the indusium to retain moisture, leading to fungal growth and spore decay. Conversely, overly dry conditions can cause it to desiccate prematurely, exposing spores to harsh conditions. Monitoring these environmental factors and their impact on indusia can inform strategies to protect pteridophyte populations in both natural and cultivated settings.

Ultimately, the indusium exemplifies the specialized adaptations of pteridophytes, offering a protective yet flexible solution for spore development and dispersal. Its role underscores the diversity of reproductive strategies in the plant kingdom and highlights the importance of understanding such structures for both scientific study and conservation efforts. By appreciating the indusium’s function, we gain a deeper insight into the resilience and complexity of these ancient plants.

Exploring Interplanetary Warfare in Spore: Strategies and Possibilities

You may want to see also

Comparison with Bryophytes: Contrasting spore dispersal methods in bryophytes and pteridophytes

Pteridophytes, such as ferns, produce spores within structures called sporangia, often clustered into sori, which may be protected by indusia—specialized coverings. In contrast, bryophytes like mosses and liverworts lack these elaborate structures, releasing spores directly from simpler capsules or sporangia typically located on unbranched stalks called setae. This fundamental difference in spore-bearing anatomy sets the stage for contrasting dispersal mechanisms between these two plant groups.

Consider the dispersal process itself. Bryophytes often rely on explosive mechanisms to eject spores from their capsules, a strategy that maximizes short-distance dispersal but limits long-range spread. For instance, in liverworts of the genus *Marchantia*, spores are forcibly discharged through elasticated openings in the sporangium, propelled by a sudden release of stored energy. Pteridophytes, however, employ more passive methods, such as wind dispersal, facilitated by the lightweight, dust-like nature of their spores and the elevated position of sori on fronds. This contrast highlights how bryophytes prioritize localized colonization, while pteridophytes aim for broader geographic reach.

The environmental contexts in which these plants thrive further underscore their dispersal adaptations. Bryophytes, typically found in moist, shaded habitats, benefit from short-distance dispersal since their spores require water for fertilization. Pteridophytes, while also favoring humid environments, often inhabit more open areas where wind currents can effectively carry spores over greater distances. For example, tree ferns elevate their spore-bearing fronds high above the forest floor, optimizing exposure to air currents.

Practical observations can illustrate these differences. In a classroom or field setting, examine a moss capsule under a microscope to observe its lid-like operculum, which pops off to release spores. Compare this to the fern's sorus, where spores trickle out gradually or are carried away en masse by wind. For educators, demonstrating these mechanisms using time-lapse photography or models can enhance student understanding of evolutionary adaptations in spore dispersal.

Ultimately, the comparison reveals how bryophytes and pteridophytes have evolved distinct spore dispersal strategies tailored to their ecological niches. While bryophytes excel in localized, moisture-dependent environments with explosive spore release, pteridophytes dominate more open habitats through passive, wind-driven dispersal. Recognizing these differences not only enriches botanical knowledge but also underscores the ingenuity of plant adaptations to diverse environments.

Mold Spores and Asthma: Uncovering the Hidden Triggers in Your Home

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, pteridophytes, such as ferns and horsetails, produce spore capsules called sporangia, which are typically located on the undersides of their leaves (fronds) or on specialized structures.

In pteridophytes, spore capsules (sporangia) are usually found on the undersides of fertile leaves or fronds, often clustered into structures called sori, or on specialized reproductive stems in some species.

The spore capsules (sporangia) in pteridophytes produce and release spores, which are essential for the plant's asexual reproduction. These spores develop into gametophytes, the sexual phase of the pteridophyte life cycle.