Seedless vascular plants, such as ferns, clubmosses, and horsetails, reproduce through spores rather than seeds. These plants have evolved specialized structures like sporangia to produce and disperse spores, which are lightweight, single-celled reproductive units. Spores allow these plants to colonize new environments efficiently, as they can travel long distances via wind or water. Unlike seed plants, which protect their embryos with a seed coat and store nutrients, seedless vascular plants rely on spores to develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes for sexual reproduction. This spore-based reproductive strategy is a hallmark of their life cycle and distinguishes them from more advanced plant groups.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Seedless vascular plants reproduce via spores, not seeds. |

| Type of Spores | Produce haploid spores through alternation of generations. |

| Sporangia Location | Spores are produced in structures called sporangia, often on leaves or stems. |

| Life Cycle | Exhibit a sporophyte-dominant life cycle, with the sporophyte generation being the most prominent. |

| Examples | Include ferns, clubmosses, horsetails, and whisk ferns. |

| Vascular Tissue | Possess xylem and phloem for water and nutrient transport. |

| Dependence on Water | Rely on water for spore dispersal and fertilization. |

| Habitat | Typically found in moist environments to support their reproductive needs. |

| Evolutionary Significance | Represent an evolutionary step between non-vascular plants and seed plants. |

| Lack of Seeds | Do not produce seeds; instead, spores develop into gametophytes. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Alternation of Generations: Seedless vascular plants alternate between sporophyte and gametophyte generations in their life cycle

- Spore Production: Spores are produced in sporangia, located on leaves or specialized structures like strobili

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals to colonize new habitats

- Gametophyte Dependence: The gametophyte phase is typically smaller and relies on moisture for survival and reproduction

- Examples of Plants: Ferns, horsetails, and clubmosses are common seedless vascular plants that produce spores

Alternation of Generations: Seedless vascular plants alternate between sporophyte and gametophyte generations in their life cycle

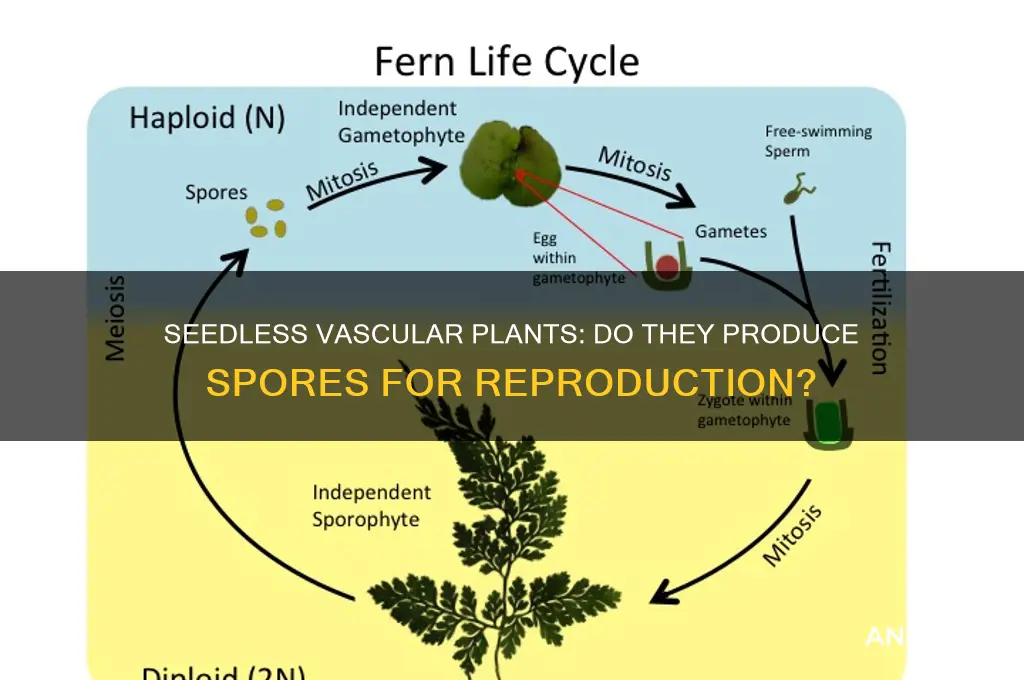

Seedless vascular plants, such as ferns and horsetails, exhibit a fascinating life cycle known as alternation of generations. This process involves two distinct phases: the sporophyte generation, which produces spores, and the gametophyte generation, which produces gametes. Understanding this cycle is crucial for anyone studying plant biology or cultivating these species.

The Sporophyte Dominance

In seedless vascular plants, the sporophyte generation is the more prominent and long-lived phase. This green, photosynthetic organism is what we typically recognize as the plant—for example, the large, feathery fronds of a fern. The sporophyte produces spores via structures like sporangia, often located on the undersides of leaves. These spores are haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. When released, they disperse through wind or water, demonstrating an efficient strategy for colonization.

Transition to the Gametophyte

Once a spore lands in a suitable environment, it germinates into a gametophyte, a smaller, less conspicuous generation. The gametophyte is also haploid and relies on moisture for survival, as it lacks true roots, stems, or leaves. Its primary function is to produce gametes—sperm and eggs—through specialized structures. For instance, in ferns, the gametophyte (called a prothallus) is heart-shaped and typically grows in damp, shaded areas. This phase highlights the plant’s dependence on water for reproduction, a trait shared by all seedless vascular plants.

Fertilization and Completion of the Cycle

Fertilization occurs when sperm from one gametophyte swims to an egg on another, facilitated by water. The resulting zygote is diploid and develops into a new sporophyte, completing the alternation of generations. This process ensures genetic diversity, as spores and gametes are produced through meiosis and fertilization, respectively. For gardeners or conservationists, maintaining moist conditions during the gametophyte stage is critical for successful reproduction.

Practical Implications

Understanding alternation of generations has practical applications, especially in horticulture. For example, fern growers must replicate humid environments to support gametophyte development. Additionally, this knowledge aids in conservation efforts, as it highlights the vulnerability of seedless vascular plants to habitat disruption, particularly in areas with reduced moisture. By studying this cycle, we gain insights into the evolutionary strategies of these plants and their adaptability to diverse ecosystems.

Seedless vascular plants’ alternation of generations is not just a biological curiosity but a key to their survival and propagation. Whether in a classroom, garden, or field, appreciating this cycle deepens our connection to the natural world and informs our efforts to protect it.

Phenols' Efficacy Against Spores: Uncovering Their Antimicrobial Potential

You may want to see also

Spore Production: Spores are produced in sporangia, located on leaves or specialized structures like strobili

Seedless vascular plants, such as ferns and horsetails, rely on spores for reproduction, a process that hinges on the production of these microscopic, single-celled structures within sporangia. These sporangia are not randomly scattered but are strategically located on specific plant parts, primarily leaves or specialized structures like strobili. This precise placement ensures efficient spore dispersal, a critical step in the plant’s life cycle. For instance, in ferns, sporangia cluster into structures called sori, typically found on the undersides of mature fronds, optimizing their exposure to air currents for dispersal.

Understanding the location of sporangia is key to identifying and cultivating these plants. For gardeners or botanists, recognizing sori on fern leaves or strobili in clubmosses can aid in species identification and care. Practical tip: When propagating ferns, gently collect spores from mature sori by placing a sheet of paper under the leaf and tapping lightly. Store the spores in a dry, cool place until ready for sowing. This method mimics natural dispersal and increases germination success.

Comparatively, the placement of sporangia in seedless vascular plants contrasts with seed plants, which enclose reproductive structures within ovules or cones. This difference highlights the evolutionary adaptation of seedless plants to rely on external conditions for spore survival and dispersal. For example, horsetails produce strobili, cone-like structures at the tips of shoots, which release spores in a manner similar to wind-pollinated plants. This adaptation ensures widespread distribution despite the lack of seeds.

From an analytical perspective, the localization of sporangia on leaves or specialized structures is a trade-off between protection and dispersal. While leaves provide a broad surface area for spore release, they offer minimal protection against environmental stressors. Specialized structures like strobili, however, offer more shelter but limit dispersal to specific periods. This balance underscores the delicate interplay between survival and reproduction in seedless vascular plants.

In conclusion, spore production in sporangia, whether on leaves or specialized structures, is a defining feature of seedless vascular plants. This mechanism not only ensures the continuation of their species but also reflects their evolutionary adaptations to diverse environments. By observing and understanding these structures, enthusiasts and professionals alike can better appreciate and support the growth of these ancient plants. Practical takeaway: Regularly inspect the undersides of fern leaves for sori to monitor reproductive health and optimize growing conditions for spore development.

Fungal Spores: Understanding Their Reproduction Through Mitosis or Meiosis

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals to colonize new habitats

Spores, the microscopic units of reproduction in seedless vascular plants, rely on external forces for dispersal to ensure species survival and colonization of new habitats. Wind, water, and animals act as primary agents in this process, each offering distinct advantages and limitations. Understanding these mechanisms provides insight into the ecological strategies of plants like ferns, clubmosses, and horsetails.

Wind dispersal is perhaps the most widespread method, favored by plants in open environments. Spores adapted for wind travel are often lightweight and equipped with structures like wings or elaters, which increase their surface area and allow them to be carried over long distances. For instance, fern spores are typically small and numerous, enabling them to disperse widely even in gentle breezes. However, this method is unpredictable, as spores may land in unsuitable habitats. To maximize success, plants often release spores in large quantities, increasing the likelihood that at least some will reach favorable conditions.

Water dispersal is common in aquatic or riparian environments, where spores can be carried by currents to new locations. Plants like certain species of quillworts and some liverworts have evolved spores that are buoyant or can withstand prolonged immersion. This method ensures that spores reach areas with consistent moisture, a critical requirement for germination. However, water dispersal is limited by the availability of water bodies and may not be effective in arid regions.

Animal dispersal, though less common, is highly targeted and efficient. Spores may adhere to the fur, feathers, or bodies of animals, which then transport them to new areas. For example, some clubmoss spores have sticky coatings that allow them to attach to passing insects. This method increases the likelihood of spores reaching suitable habitats, as animals often frequent areas with resources conducive to plant growth. However, it relies on the presence and movement of specific animal species, making it less reliable than wind or water dispersal.

Each dispersal mechanism reflects adaptations to the plant’s environment and life cycle. Wind and water dispersal are passive, relying on natural forces, while animal dispersal involves a degree of biological interaction. By leveraging these methods, seedless vascular plants ensure genetic diversity and expand their geographic range, even in the absence of seeds. Practical observations of these mechanisms can inform conservation efforts, such as preserving wind corridors or maintaining water flow in habitats where these plants thrive.

Troubleshooting Spore Login Issues: Quick Fixes to Get Back in the Game

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gametophyte Dependence: The gametophyte phase is typically smaller and relies on moisture for survival and reproduction

Seedless vascular plants, such as ferns and lycophytes, exhibit a unique life cycle where the gametophyte phase plays a critical role in reproduction. Unlike the sporophyte phase, which is larger and more prominent, the gametophyte is diminutive and often goes unnoticed. This smaller phase is not merely a transitional stage but a vital component that ensures the continuation of the species. Its survival and reproductive success hinge on one essential factor: moisture.

Consider the environment in which these gametophytes thrive. They are typically found in damp, shaded areas where humidity levels remain consistently high. For instance, fern gametophytes (prothalli) require a thin film of water to facilitate sperm movement from the antheridia to the archegonia, where fertilization occurs. Without adequate moisture, these sperm cannot swim, rendering reproduction impossible. Practical tip: If cultivating seedless vascular plants, maintain a humidity level of at least 60% and ensure the substrate remains moist but not waterlogged to support gametophyte development.

The dependence on moisture extends beyond reproduction to the gametophyte’s overall survival. These organisms lack true roots, stems, and leaves, making them structurally simple and vulnerable to desiccation. Their small size, often just a few millimeters, limits their ability to store water, further emphasizing their reliance on external moisture. Comparative analysis reveals that while sporophytes have vascular tissues to transport water and nutrients, gametophytes must absorb moisture directly from their surroundings, underscoring their fragility and environmental specificity.

To illustrate, lycophyte gametophytes, such as those of the genus *Selaginella*, are particularly sensitive to drying conditions. They often grow in clusters on moist soil or decaying wood, where they can quickly absorb water through their thin, delicate tissues. In contrast, fern gametophytes may survive slightly longer in suboptimal conditions due to their slightly more robust structure, but both ultimately perish without consistent moisture. Caution: Avoid exposing gametophytes to direct sunlight or dry air, as even brief periods of dehydration can be fatal.

In conclusion, the gametophyte phase of seedless vascular plants exemplifies a delicate balance between simplicity and dependency. Its small size and reliance on moisture highlight the evolutionary trade-offs between efficiency and vulnerability. By understanding these requirements, enthusiasts and researchers can better cultivate and study these plants, ensuring their preservation in both natural and controlled environments. Practical takeaway: Regularly mist the growing area and monitor moisture levels to mimic the gametophyte’s natural habitat, fostering successful growth and reproduction.

Mastering Morel Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Planting Spores

You may want to see also

Examples of Plants: Ferns, horsetails, and clubmosses are common seedless vascular plants that produce spores

Seedless vascular plants, a fascinating group in the plant kingdom, rely on spores for reproduction rather than seeds. Among these, ferns, horsetails, and clubmosses stand out as prime examples. These plants share a common trait: they produce spores as part of their life cycle, ensuring their survival and propagation in diverse environments. Understanding these examples not only highlights their reproductive strategies but also underscores their ecological significance.

Ferns, perhaps the most recognizable seedless vascular plants, thrive in moist, shaded environments. Their life cycle involves alternating generations, with the sporophyte (spore-producing) phase dominant. On the underside of fern fronds, you’ll find sori, clusters of sporangia that release spores. These spores develop into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes, which in turn produce eggs and sperm. For gardeners cultivating ferns, maintaining consistent moisture and indirect light is crucial to support their spore-driven reproduction.

Horsetails, another example, are ancient plants with a distinctive jointed appearance. They produce spores in cone-like structures at the tips of their stems. Unlike ferns, horsetails are often found in wet, sandy soils and can tolerate harsh conditions. Their spores are dispersed by wind, allowing them to colonize new areas. While horsetails are less commonly cultivated, they serve as a reminder of the resilience of spore-producing plants in challenging environments.

Clubmosses, though often mistaken for mosses, are true seedless vascular plants. They produce spores in structures called strobili, which resemble tiny clubs—hence their name. These plants are typically found in woodland areas and have a creeping growth habit. Clubmoss spores are lightweight and easily dispersed, enabling them to thrive in diverse habitats. For enthusiasts, observing clubmosses in their natural habitat provides insight into the efficiency of spore reproduction in maintaining plant diversity.

In summary, ferns, horsetails, and clubmosses exemplify the adaptability of seedless vascular plants through their spore-producing capabilities. Each has evolved unique strategies to ensure spore dispersal and survival, from the delicate sori of ferns to the resilient strobili of clubmosses. By studying these examples, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity and ingenuity of plant reproductive systems in the absence of seeds.

Hot Heat vs. Ringworm Spores: Can High Temperatures Eliminate Them?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, seedless vascular plants, such as ferns and horsetails, reproduce via spores as their primary method of reproduction.

Seedless vascular plants release spores that develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes (sperm and eggs) to form new plants through fertilization.

Yes, spores are the primary reproductive method for seedless vascular plants, as they lack seeds and flowers for reproduction.

Seedless vascular plants release spores from structures like sporangia, often found on the undersides of leaves (e.g., fern fronds) or specialized stems.