Fungal spores are a critical aspect of fungal reproduction and dispersal, but the process by which they are produced varies depending on the type of spore and the fungal life cycle. Generally, fungal spores can be generated through either mitosis or meiosis, each serving distinct purposes. Mitosis is involved in the asexual production of spores, such as conidia, which are genetically identical to the parent fungus and allow for rapid proliferation under favorable conditions. In contrast, meiosis is central to the sexual reproduction of fungi, producing spores like asci or basidiospores, which result from genetic recombination and are crucial for genetic diversity and survival in changing environments. Understanding whether fungal spores arise from mitosis or meiosis is essential for comprehending their roles in fungal biology, ecology, and evolution.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Spores | Fungal spores can be produced via both mitosis and meiosis, depending on the type of spore and the fungal life cycle stage. |

| Asexual Spores | Produced via mitosis (e.g., conidia, spores, and budding cells). These spores are genetically identical to the parent fungus. |

| Sexual Spores | Produced via meiosis (e.g., asci, basidiospores, and zygospores). These spores result from genetic recombination and are genetically diverse. |

| Function | Asexual spores serve for vegetative reproduction and dispersal, while sexual spores are involved in genetic diversity and survival under adverse conditions. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Mitosis occurs during the haploid or diploid vegetative phase, while meiosis occurs during the sexual reproduction phase. |

| Examples | Mitosis: Yeast budding, mold conidia. Meiosis: Ascomycetes (ascospores), Basidiomycetes (basidiospores). |

| Genetic Outcome | Mitosis produces clones, while meiosis produces genetically unique spores. |

| Environmental Role | Asexual spores are common in favorable conditions, while sexual spores are often produced in response to stress or nutrient depletion. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Both types of spores are adapted for dispersal (e.g., wind, water, animals), but sexual spores often have thicker walls for survival. |

| Taxonomic Distribution | Mitosis and meiosis are found across all major fungal phyla, but the dominance of one over the other varies by group. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Fungal spore formation process

Fungal spores are primarily the product of meiosis, a specialized cell division process that reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid cells. This is a critical distinction from mitosis, which produces genetically identical daughter cells with the same chromosome number as the parent. In fungi, meiosis occurs during the sexual phase of their life cycle, leading to the formation of spores such as asci or basidiospores, depending on the fungal group. These spores are essential for genetic diversity and survival in varying environmental conditions.

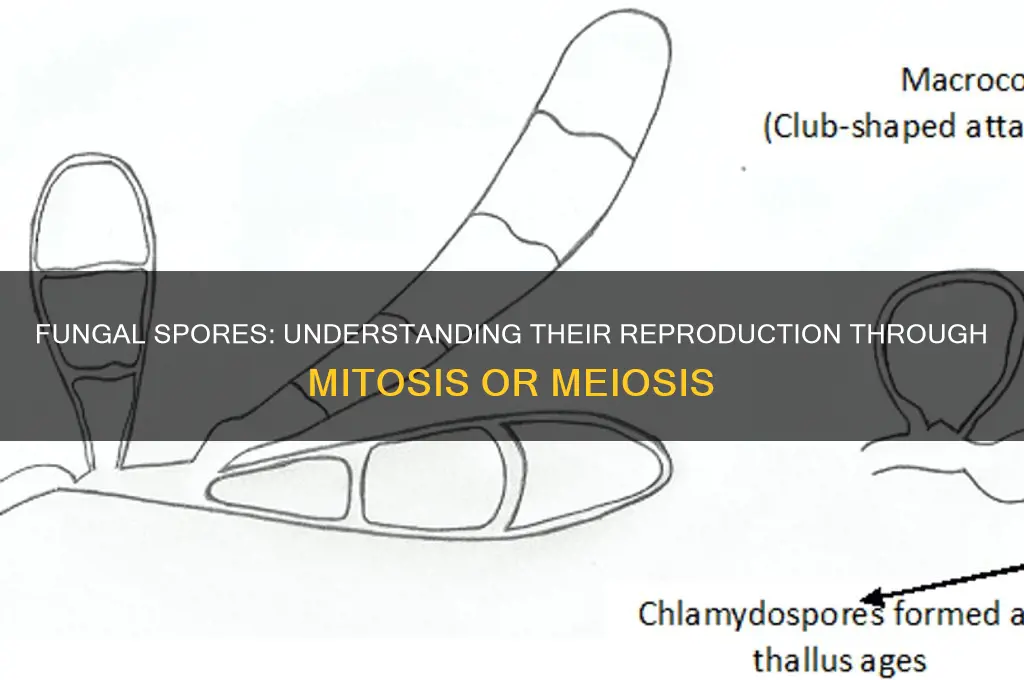

The fungal spore formation process begins with the fusion of two compatible haploid cells, known as gametangia, during sexual reproduction. This fusion results in a diploid zygote, which then undergoes meiosis to restore the haploid state. For example, in Ascomycetes, the zygote develops into an ascus, a sac-like structure where meiosis occurs, producing eight haploid ascospores. Similarly, in Basidiomycetes, the zygote forms a basidium, a club-shaped structure that undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid basidiospores. These spores are then released into the environment, where they can germinate under favorable conditions.

Understanding the role of meiosis in spore formation is crucial for practical applications, such as controlling fungal pathogens in agriculture. For instance, knowing that spores are haploid and genetically diverse helps in developing fungicides that target specific metabolic pathways unique to these cells. Additionally, in biotechnology, fungal spores are used in the production of enzymes and antibiotics, where their genetic diversity can be harnessed for optimizing yields. For home gardeners, recognizing that spores are the result of sexual reproduction highlights the importance of managing fungal populations through crop rotation and reducing environmental stressors to prevent spore germination.

A comparative analysis of spore formation in different fungal groups reveals variations in structure and dispersal mechanisms. For example, Zygomycetes produce sporangiospores through mitosis, but these are asexual spores (conidia) and not the primary focus here. In contrast, the sexual spores of Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes are meiotic and exhibit distinct dispersal strategies. Ascospores are often forcibly ejected from the ascus, while basidiospores are released passively. These differences underscore the adaptability of fungi to diverse ecological niches and their reliance on meiosis for long-term survival.

In conclusion, the fungal spore formation process is a meiotic event that ensures genetic diversity and adaptability. By focusing on the mechanisms and outcomes of meiosis in fungi, we gain insights into their life cycles and practical applications. Whether in agriculture, biotechnology, or gardening, understanding this process empowers us to manage fungal populations effectively and harness their potential for human benefit.

Effective Milky Spore Powder Application: A Guide to Grub Control

You may want to see also

Mitosis vs meiosis in fungi

Fungal spores are the result of two distinct cellular processes: mitosis and meiosis. Understanding which process produces which type of spore is crucial for fields like mycology, agriculture, and medicine. Asexual spores, such as conidia and chlamydospores, arise from mitosis, a process that maintains the parent organism’s genetic material. These spores are clones, ideal for rapid colonization in stable environments. In contrast, sexual spores, like asci and basidiospores, are products of meiosis, a process that introduces genetic diversity through recombination. These spores are better suited for survival in changing or harsh conditions. This distinction highlights the adaptive strategies fungi employ to thrive in diverse ecosystems.

Consider the life cycle of *Aspergillus fumigatus*, a common mold. When nutrients are abundant, it produces conidia via mitosis, allowing it to spread quickly across surfaces. However, under stress or nutrient scarcity, it shifts to meiosis, forming ascospores that can endure extreme conditions. This dual strategy illustrates how fungi balance efficiency and resilience. For practical applications, such as controlling fungal infections or optimizing fermentation processes, understanding these mechanisms is essential. For instance, antifungal treatments targeting mitotic spores may fail against meiotic spores, underscoring the need for targeted approaches.

From a comparative perspective, mitosis and meiosis in fungi serve complementary roles. Mitosis is straightforward: one cell divides into two identical copies, preserving the genetic integrity of the parent. This process is energy-efficient and rapid, making it ideal for vegetative growth. Meiosis, however, is more complex, involving two rounds of division and genetic shuffling. While slower and more resource-intensive, it generates diversity, a key advantage in unpredictable environments. For example, meiotic spores of *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (yeast) enable it to adapt to varying sugar concentrations in its habitat, a trait exploited in brewing and baking.

To differentiate between mitotic and meiotic spores in a laboratory setting, observe their structure and context. Mitotic spores, like conidia, are typically single-celled and produced on specialized structures (e.g., conidiophores). Meiotic spores, such as asci or basidiospores, are often multicellular and formed within fruiting bodies. A simple test involves culturing spores under stress conditions; mitotic spores may fail to germinate, while meiotic spores are more likely to survive. For educators, demonstrating this difference using *Neurospora crassa* (a model fungus) can engage students in the practical implications of these processes.

In conclusion, the distinction between mitosis and meiosis in fungi is not merely academic—it has tangible implications for science and industry. Mitosis drives rapid proliferation, while meiosis ensures long-term survival through diversity. By recognizing these processes, researchers can develop more effective antifungal strategies, farmers can manage crop diseases, and biotechnologists can harness fungal capabilities. Whether you’re a student, scientist, or enthusiast, grasping this duality unlocks a deeper appreciation of fungi’s ecological and economic significance.

Exploring Fern Reproduction: Do Ferns Bear Spores for Growth?

You may want to see also

Haploid vs diploid fungal spores

Fungal spores are a fascinating aspect of fungal biology, and understanding their ploidy—whether they are haploid or diploid—is crucial to grasping their role in the fungal life cycle. Fungal spores can be either haploid or diploid, depending on the species and the stage of their life cycle. Haploid spores contain a single set of chromosomes, while diploid spores have two sets. This distinction is fundamental because it determines how these spores contribute to genetic diversity and the survival strategies of fungi.

Consider the life cycle of *Aspergillus*, a common mold. It produces haploid spores called conidia through mitosis. These spores are asexual and serve primarily for dispersal and rapid colonization of new environments. In contrast, during sexual reproduction, *Aspergillus* forms diploid zygospores through meiosis, which then undergo karyogamy to restore the haploid state. This dual strategy highlights how fungi leverage both haploid and diploid spores to adapt to varying ecological conditions. Haploid spores are efficient for quick proliferation, while diploid spores enhance genetic recombination and resilience.

To illustrate further, examine the basidiomycetes, such as mushrooms. They produce haploid basidiospores via meiosis, which germinate into haploid mycelia. When two compatible mycelia fuse, they form a diploid structure that eventually produces new basidiospores. This alternation of generations—between haploid and diploid phases—is a hallmark of sexual reproduction in fungi. It ensures genetic diversity, which is critical for adapting to changing environments and resisting pathogens.

Practical implications of this knowledge are significant, especially in agriculture and medicine. For instance, understanding whether a fungal pathogen produces haploid or diploid spores can guide the development of fungicides. Haploid spores, being more numerous and rapidly produced, may require targeted disruption of mitotic processes, while diploid spores might necessitate strategies to inhibit meiosis or spore maturation. Farmers and researchers can use this information to devise more effective control measures, reducing crop losses and minimizing resistance development.

In summary, the distinction between haploid and diploid fungal spores is not merely academic—it has tangible applications in managing fungal populations. Haploid spores, often produced asexually, dominate in environments favoring rapid growth, while diploid spores, typically resulting from sexual reproduction, enhance genetic diversity. By recognizing these differences, we can better predict fungal behavior, develop targeted interventions, and appreciate the evolutionary elegance of these organisms. Whether in a laboratory or a field, this knowledge empowers us to coexist more effectively with the fungal kingdom.

Understanding Dangerous Mold Spore Levels: Health Risks and Safety Thresholds

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of spores in fungal life cycle

Fungal spores are not just passive agents of dispersal; they are dynamic structures that encapsulate the essence of fungal survival and reproduction. To understand their role in the fungal life cycle, it’s crucial to distinguish between the two primary types of spores: mitospores and meiospores. Mitospores, produced through mitosis, are asexual and serve primarily for vegetative growth and rapid colonization. Meiospores, on the other hand, result from meiosis and are involved in sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic diversity. This distinction is fundamental to grasping how fungi adapt, thrive, and evolve in diverse environments.

Consider the life cycle of a common fungus like *Aspergillus*. When conditions are favorable, it produces conidia (mitospores) that disperse through air or water. These spores germinate quickly, forming new mycelium and extending the fungal colony. This asexual phase is efficient for exploiting resources in stable environments. However, when nutrients deplete or stress occurs, the fungus shifts to sexual reproduction, producing ascospores (meiospores) through meiosis. These spores are more resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions, and carry unique genetic combinations, enhancing the species’ adaptability.

The role of spores extends beyond mere reproduction; they are survival mechanisms. For instance, zygotes in fungi like mushrooms form thick-walled zygospores that can remain dormant for years, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. Similarly, basidiospores in mushrooms are meiospores that ensure genetic recombination, a critical factor in fungal evolution. This dual strategy—rapid asexual reproduction via mitosis and long-term survival through meiosis—highlights the versatility of spores in the fungal life cycle.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in agriculture and medicine. Farmers use trichoderma mitospores as biocontrol agents to combat plant pathogens, leveraging their rapid colonization abilities. Conversely, understanding meiospores is vital in managing fungal diseases, as these spores can introduce new strains resistant to antifungal treatments. For instance, *Candida albicans* produces chlamydospores (thick-walled, resilient meiospores) that contribute to recurrent infections, making them a target for antifungal drug development.

In conclusion, spores are not just reproductive units but strategic tools in the fungal life cycle. Mitospores drive rapid growth and colonization, while meiospores ensure genetic diversity and long-term survival. By understanding their roles, we can harness their potential in biotechnology and mitigate their impact in disease management. Whether through mitosis or meiosis, spores exemplify the ingenuity of fungal life, blending efficiency with resilience.

Mastering Jungle Spore Collection: Essential Tips and Techniques Revealed

You may want to see also

Differences in spore production methods

Fungal spores are produced through distinct cellular processes, each tailored to the fungus's life cycle and environmental needs. The primary methods involve mitosis and meiosis, but their application varies significantly across fungal groups. Understanding these differences is crucial for fields like mycology, agriculture, and medicine, where spore behavior impacts disease spread, food production, and ecosystem dynamics.

Mitosis dominates asexual spore production, generating genetically identical offspring. Fungi like molds (e.g., *Aspergillus*) and yeasts (e.g., *Saccharomyces*) rely on this process to rapidly colonize nutrient-rich environments. Asexual spores, such as conidia or blastospores, are formed via repeated cell divisions without genetic recombination. This method ensures consistency in traits beneficial for survival but limits adaptability to changing conditions. For instance, a single *Aspergillus* colony can produce millions of conidia daily, each capable of initiating a new colony under favorable conditions.

In contrast, meiosis drives sexual spore production, introducing genetic diversity through recombination. Fungi like mushrooms (e.g., *Agaricus*) and rusts (e.g., *Puccinia*) use this process to create spores such as basidiospores or asci. Sexual spores are typically produced in response to environmental stressors, such as nutrient depletion or temperature shifts. For example, the fusion of haploid cells (karyogamy) in *Agaricus* results in a diploid zygote, which undergoes meiosis to form four haploid basidiospores. This genetic shuffling enhances resilience, enabling fungi to survive harsh conditions or evade host defenses.

Key differences between these methods extend beyond genetics. Asexual spores are often smaller, lighter, and more numerous, optimized for wind or water dispersal. Sexual spores, while fewer, are more robust, with thicker walls to withstand desiccation or predation. For instance, *Neurospora* ascospores can remain viable for years, while conidia typically germinate within hours to days. Additionally, the timing and triggers for spore production differ: asexual spores are produced continuously in stable environments, whereas sexual spores require specific cues, such as mating pheromones or seasonal changes.

Practical implications of these differences are profound. In agriculture, understanding spore production helps manage fungal pathogens like *Botrytis* (gray mold) or *Magnaporthe* (rice blast). For example, disrupting meiosis in *Magnaporthe* could reduce its ability to adapt to fungicides, while targeting mitosis in *Botrytis* could limit its rapid spread. Similarly, in biotechnology, manipulating spore production methods can enhance fungal strains for industrial applications, such as enzyme production or biofuel fermentation. By leveraging these distinctions, researchers and practitioners can develop more effective strategies for fungal control or utilization.

Exploring the Microscopic World: What Does a Spore Really Look Like?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungal spores can be produced through either mitosis or meiosis, depending on the type of spore and the fungal life cycle stage.

Vegetative spores, such as conidia and chlamydospores, are typically produced through mitosis and are used for asexual reproduction.

Sexual spores, such as asci, basidiospores, and zygospores, are produced through meiosis and are part of the sexual reproductive cycle in fungi.