Spore-producing plants, such as ferns, mosses, and fungi, differ fundamentally from flowering plants in their reproductive strategies, raising the question of whether they rely on bees for survival. Unlike flowering plants, which depend on pollinators like bees to transfer pollen for seed production, spore-producing plants reproduce through spores, which are dispersed by wind, water, or other environmental factors. This asexual method of reproduction eliminates the need for pollinators, making bees unnecessary for their life cycle. Consequently, while bees play a critical role in the ecosystems of flowering plants, spore-producing plants thrive independently, relying instead on their ability to disperse spores efficiently in their natural habitats.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Spore-producing plants (e.g., ferns, mosses, fungi) reproduce via spores, not seeds. |

| Need for Pollinators | No, spore-producing plants do not require bees or other pollinators for reproduction. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or other environmental factors, not by animals or insects. |

| Dependency on Bees | None; bees play no role in the reproductive cycle of spore-producing plants. |

| Flowering Structures | Absent; spore-producing plants do not produce flowers. |

| Nectar Production | None; these plants do not produce nectar to attract pollinators. |

| Ecological Role of Bees | Bees are irrelevant to spore-producing plants but are crucial for seed-producing plants (angiosperms). |

| Examples of Plants | Ferns, mosses, liverworts, fungi (e.g., mushrooms). |

| Evolutionary Context | Spore-producing plants are older than seed plants and evolved before pollinators like bees existed. |

| Habitat Adaptation | Often found in moist environments where spores can easily germinate without pollinator assistance. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore vs. Seed Dispersal: How do spores differ from seeds in plant reproduction and dispersal methods

- Fungal Spores and Bees: Do bees play any role in the dispersal of fungal spores

- Fern Reproduction Cycle: How do ferns reproduce without flowers or pollinators like bees

- Moss and Liverwort Spores: Do mosses and liverworts rely on external agents for spore dispersal

- Wind vs. Animal Dispersal: How do spore-producing plants compare to flowering plants in dispersal strategies

Spore vs. Seed Dispersal: How do spores differ from seeds in plant reproduction and dispersal methods?

Spore-producing plants, such as ferns and mosses, rely on a fundamentally different reproductive strategy compared to seed-producing plants like flowering plants. While seeds are encased in protective structures that contain stored nutrients for the developing embryo, spores are single-celled, lightweight, and lack these resources. This distinction shapes their dispersal methods and ecological roles. Spores are dispersed primarily through wind, water, or passive mechanisms, allowing them to travel vast distances with minimal energy investment. Seeds, on the other hand, often require external agents like animals, wind, or water for dispersal, and some, particularly flowering plants, depend on pollinators like bees for reproduction. This raises the question: do spore-producing plants need bees? The answer is no, as their reproductive cycle bypasses the need for pollinators entirely.

Consider the dispersal mechanisms of spores versus seeds to understand their ecological efficiency. Spores, being microscopic and numerous, are produced in vast quantities, ensuring that at least some land in suitable environments for growth. For example, a single fern can release millions of spores in a single season. This strategy, known as "scatter and hope," maximizes the chances of survival despite the lack of nutrients in each spore. Seeds, however, are larger, energy-dense, and often dispersed in limited quantities. They rely on precision—whether carried by animals, wind, or water—to reach fertile ground. This difference highlights why spore-producing plants thrive in diverse habitats, from damp forests to rocky outcrops, without needing specialized pollinators like bees.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences can inform conservation efforts and gardening practices. For instance, if you’re cultivating spore-producing plants like ferns or mosses, focus on creating a humid, shaded environment rather than attracting pollinators. Spores can be manually dispersed by sprinkling them on moist soil or even mixing them with water for wider coverage. In contrast, seed-producing plants, especially flowering species, benefit from bee-friendly practices such as planting nectar-rich flowers or avoiding pesticides. For gardeners, this means tailoring your approach based on the plant’s reproductive strategy—spore-producing plants require habitat management, while seed-producing plants need pollinator support.

A comparative analysis reveals the trade-offs between spores and seeds. Spores’ simplicity and lightweight nature make them highly adaptable but dependent on external conditions for germination. Seeds, with their protective coats and nutrient reserves, offer a higher chance of individual success but require more energy to produce. This evolutionary divergence explains why spore-producing plants dominate in environments where rapid colonization is key, such as after disturbances like wildfires or landslides. Seed-producing plants, meanwhile, excel in stable ecosystems where competition for resources is high. For example, ferns quickly colonize forest floors after logging, while trees rely on seeds to establish new generations over decades.

In conclusion, the reproductive strategies of spore-producing and seed-producing plants reflect their ecological niches and survival tactics. Spores’ reliance on quantity and passive dispersal eliminates the need for pollinators like bees, making them self-sufficient in reproduction. Seeds, however, often depend on external agents, including pollinators, for successful dispersal and germination. By recognizing these differences, we can better appreciate the diversity of plant life and implement targeted strategies for their cultivation and conservation. Whether you’re a gardener, ecologist, or enthusiast, understanding spore vs. seed dispersal provides valuable insights into the natural world.

Mildew Spores in Your Home: Uncovering the Link to Hair Loss

You may want to see also

Fungal Spores and Bees: Do bees play any role in the dispersal of fungal spores?

Fungi, unlike plants, do not rely on pollinators for reproduction. Their spores are typically dispersed by wind, water, or even explosive mechanisms. This fundamental difference raises the question: do bees, masters of plant pollination, have any role in the dispersal of fungal spores?

While bees are not essential for fungal reproduction, evidence suggests a fascinating, if indirect, relationship. Some fungi form symbiotic relationships with plants, known as mycorrhizae, which enhance nutrient uptake for the plant. Bees, in turn, are attracted to these healthier plants for nectar and pollen. This creates a scenario where bees, while not directly dispersing spores, may inadvertently contribute to fungal spread by frequenting plants associated with specific fungi.

Imagine a bee visiting a flower colonized by a particular mycorrhizal fungus. As the bee collects nectar, fungal spores could adhere to its body. When the bee visits another flower, some spores might be transferred, potentially establishing a new fungal colony. This passive dispersal mechanism, though not the primary method for fungi, highlights a subtle ecological connection between these seemingly disparate organisms.

Further research is needed to quantify the significance of bee-mediated fungal spore dispersal. Studies could investigate spore adhesion to bee bodies, survival rates during transport, and successful colonization at new sites. Understanding this potential interaction could shed light on the complex web of relationships within ecosystems and the unexpected ways different species influence each other's success.

Identifying Mold Spores: Signs, Symptoms, and Testing Methods for Your Home

You may want to see also

Fern Reproduction Cycle: How do ferns reproduce without flowers or pollinators like bees?

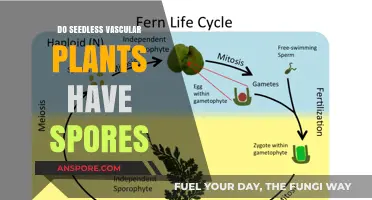

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, bypass the need for bees or any pollinators in their reproduction cycle. Instead of relying on external agents to transfer genetic material, ferns employ a unique and ancient method of reproduction: spore production. This process, known as alternation of generations, involves two distinct life stages—the sporophyte (the plant we recognize as a fern) and the gametophyte (a small, heart-shaped structure). Understanding this cycle not only highlights the self-sufficiency of ferns but also underscores the diversity of plant reproductive strategies.

The reproduction cycle begins with the mature fern releasing spores from structures called sporangia, typically found on the undersides of its fronds. These spores are microscopic and lightweight, allowing them to be dispersed by wind or water over considerable distances. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment—moist, shaded, and rich in organic matter—it germinates into a gametophyte. This tiny, photosynthetic organism is often overlooked but plays a critical role in the fern’s life cycle. The gametophyte produces both sperm and eggs, ensuring that fertilization can occur without the need for pollinators.

Fertilization in ferns is a water-dependent process, as sperm require moisture to swim from the male organs (antheridia) to the female organs (archegonia) on the same or neighboring gametophytes. Once fertilization occurs, a new sporophyte begins to grow, eventually developing into the familiar fern plant. This cycle eliminates the need for flowers, nectar, or pollinators, making ferns entirely self-sufficient in their reproductive process. For gardeners or enthusiasts, this means ferns can thrive in environments where bees or other pollinators are absent, such as shaded forests or indoor settings.

A practical takeaway for cultivating ferns is to mimic their natural habitat. Ensure the soil remains consistently moist to facilitate spore germination and sperm mobility. Provide indirect light and maintain humidity levels, as ferns are adapted to understory environments. Avoid over-fertilizing, as ferns thrive in nutrient-poor soils. By understanding and supporting their unique reproductive cycle, you can successfully grow ferns without relying on external pollinators, making them an excellent choice for low-maintenance, pollinator-independent gardening.

Fall Application of Milky Spore: Timing and Effectiveness for Grub Control

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Moss and Liverwort Spores: Do mosses and liverworts rely on external agents for spore dispersal?

Mosses and liverworts, unlike their flowering counterparts, do not produce seeds but rely on spores for reproduction. These tiny, single-celled units are housed in structures called sporangia, often perched atop slender stalks. The question arises: how do these spores travel to new habitats without the aid of bees or other pollinators? The answer lies in the ingenious mechanisms these plants have evolved for spore dispersal, which are both passive and highly efficient.

Consider the role of wind in spore dispersal. Mosses and liverworts often grow in dense mats or cushions, strategically positioning their sporangia to catch air currents. When mature, the sporangia dry out and split open, releasing spores that are lightweight and easily carried by even the gentlest breeze. This method, known as anemochory, allows spores to travel significant distances, sometimes kilometers, without the need for external agents like bees. For instance, the spores of the common liverwort *Marchantia polymorpha* are so fine that they can remain suspended in air for hours, increasing their chances of reaching new substrates.

Water also plays a crucial role in spore dispersal for certain mosses and liverworts, particularly those inhabiting moist environments. Splashes from raindrops or flowing water can dislodge spores from the sporangia, carrying them to nearby areas. This mechanism, termed splash dispersal, is especially effective in humid ecosystems like rainforests or wetlands. For example, the aquatic liverwort *Riccia fluitans* relies on water movement to distribute its spores across the surface of ponds and streams. While this method is more localized compared to wind dispersal, it ensures that spores land in suitable habitats where moisture is abundant.

Another fascinating strategy is the use of explosive mechanisms. Some mosses and liverworts have evolved sporangia that discharge spores with force, akin to tiny cannons. This ballistic dispersal is triggered by changes in humidity or drying, propelling spores several centimeters away from the parent plant. The moss genus *Sphagnum*, for instance, employs this method to scatter its spores across peatlands. While the range is limited, the precision ensures that spores land in nearby areas with similar environmental conditions, optimizing their chances of germination.

Despite these adaptations, it’s worth noting that mosses and liverworts do not entirely exclude external agents from their reproductive cycle. Small invertebrates, such as springtails or mites, may inadvertently carry spores on their bodies as they move through the vegetation. However, this is a secondary mechanism and not a dependency. Unlike flowering plants that rely on bees for pollination, mosses and liverworts have evolved self-sufficient strategies that minimize their reliance on external vectors.

In conclusion, mosses and liverworts have mastered the art of spore dispersal through a combination of passive and active mechanisms. Wind, water, and explosive discharges ensure that their spores reach new habitats efficiently, without the need for bees or other pollinators. These adaptations highlight the resilience and ingenuity of non-vascular plants, which thrive in diverse environments by leveraging natural forces to perpetuate their life cycle. For enthusiasts or researchers studying these plants, observing their spore dispersal methods offers valuable insights into the evolutionary strategies of Earth’s earliest land plants.

Mange Mites and Dog Aggression: Unraveling the Behavioral Connection

You may want to see also

Wind vs. Animal Dispersal: How do spore-producing plants compare to flowering plants in dispersal strategies?

Spore-producing plants, such as ferns and mosses, rely on wind dispersal for reproduction, a stark contrast to the animal-dependent strategies of flowering plants. Unlike seeds, spores are lightweight and produced in vast quantities, allowing them to travel long distances on air currents. This method is efficient but lacks precision, as spores are scattered indiscriminately, landing in environments that may or may not support growth. For instance, a single fern can release millions of spores annually, yet only a fraction will find suitable conditions to develop into new plants. This high-volume, low-accuracy approach is a hallmark of wind dispersal, emphasizing quantity over targeted placement.

Flowering plants, on the other hand, have evolved intricate relationships with animals, particularly bees, for seed dispersal. These plants invest energy in producing flowers, nectar, and fruits to attract pollinators and seed dispersers. Bees, for example, visit flowers for nectar and inadvertently transfer pollen, facilitating fertilization. This mutualistic relationship ensures that seeds are deposited in locations more likely to support germination and growth. Consider the apple tree, which relies on bees for pollination and animals like birds and mammals to disperse its seeds. This targeted strategy increases the chances of successful reproduction, even though it requires more energy and specificity than wind dispersal.

Comparing these strategies reveals trade-offs between energy investment and dispersal success. Spore-producing plants allocate minimal energy to individual spores, relying on sheer numbers and wind to achieve reproduction. Flowering plants, however, invest heavily in structures like flowers and fruits, trading energy for precision. For gardeners or conservationists, understanding these differences is crucial. When cultivating spore-producing plants, ensure they are in open areas with good air circulation to maximize spore dispersal. For flowering plants, prioritize planting bee-friendly species and creating habitats that attract pollinators to enhance seed dispersal.

A practical takeaway is that spore-producing plants thrive in environments where wind is consistent, such as open fields or forest edges. In contrast, flowering plants benefit from diverse ecosystems rich in animal activity. For instance, a garden designed to support both strategies might include ferns and mosses in windy, shaded areas, while placing flowering plants like sunflowers or lavender in sunny spots frequented by bees. By tailoring habitats to these dispersal methods, one can optimize plant reproduction and biodiversity.

Ultimately, the choice between wind and animal dispersal reflects evolutionary adaptations to specific environments. Spore-producing plants excel in simplicity and abundance, while flowering plants leverage complexity and collaboration. Neither strategy is inherently superior; each is suited to its ecological niche. For those interested in plant reproduction, studying these differences offers insights into the delicate balance between energy, precision, and survival in the natural world.

Do Mold Spores Stick to Clothes? Understanding Contamination Risks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spore-producing plants, such as ferns and mosses, do not need bees for reproduction. They reproduce via spores, not seeds, and do not rely on pollinators.

Spore-producing plants reproduce through a process called alternation of generations, where they alternate between a sporophyte (spore-producing) stage and a gametophyte (gamete-producing) stage, without the need for pollinators like bees.

Bees are generally not attracted to spore-producing plants because these plants do not produce flowers, nectar, or pollen, which are the primary resources bees seek.

Spore-producing plants do not benefit from bees since they do not rely on pollinators. Bees play no role in their reproductive cycle or survival.

No, spore-producing plants and flowering plants have different reproductive strategies. Flowering plants depend on pollinators like bees for seed production, while spore-producing plants reproduce independently through spores.