Spores, which are reproductive structures produced by various organisms such as bacteria, fungi, and plants, do not multiply by binary fission themselves. Binary fission is a form of asexual reproduction primarily associated with prokaryotic organisms like bacteria, where a single cell divides into two identical daughter cells. Spores, on the other hand, are typically the result of a specialized reproductive process, such as sporulation in bacteria or fungi, or spore formation in plants. Once formed, spores can germinate under favorable conditions to produce new individuals, but they do not undergo binary fission. Instead, spores serve as a means of survival and dispersal, allowing organisms to endure harsh environments and colonize new habitats.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Method of Multiplication | Spores do not multiply by binary fission. Instead, they are reproductive structures produced by certain organisms (e.g., bacteria, fungi, plants) to survive harsh conditions. |

| Binary Fission | A form of asexual reproduction where a single organism divides into two identical daughter cells, typically seen in prokaryotes like bacteria. |

| Spore Formation | Spores are formed through processes like sporulation (in bacteria) or meiosis (in fungi and plants), not binary fission. |

| Function of Spores | Spores are dormant, resilient structures that can withstand extreme conditions (e.g., heat, dryness) and germinate into new organisms when conditions improve. |

| Binary Fission in Spores | Spores themselves do not undergo binary fission; they germinate and grow into new organisms that may later reproduce via binary fission (in bacteria) or other methods. |

| Organisms Involved | Binary fission is common in bacteria, while spore formation is seen in bacteria (endospores), fungi, plants, and some protists. |

| Genetic Variation | Binary fission produces genetically identical offspring, whereas spores often involve genetic recombination (in fungi and plants) or are haploid (in plants). |

| Environmental Role | Spores serve as survival mechanisms, while binary fission is a rapid reproduction method in favorable conditions. |

Explore related products

$9.99

What You'll Learn

- Binary Fission Process: Single spore divides into two identical daughter spores, doubling genetic material

- Conditions for Fission: Requires favorable environment: nutrients, moisture, temperature, and stable conditions

- Spores vs. Vegetative Cells: Spores are dormant; binary fission occurs in active vegetative cells

- Role in Reproduction: Binary fission is asexual, rapidly increasing spore population under optimal conditions

- Comparison to Sporulation: Sporulation forms spores; binary fission multiplies vegetative cells, not spores directly

Binary Fission Process: Single spore divides into two identical daughter spores, doubling genetic material

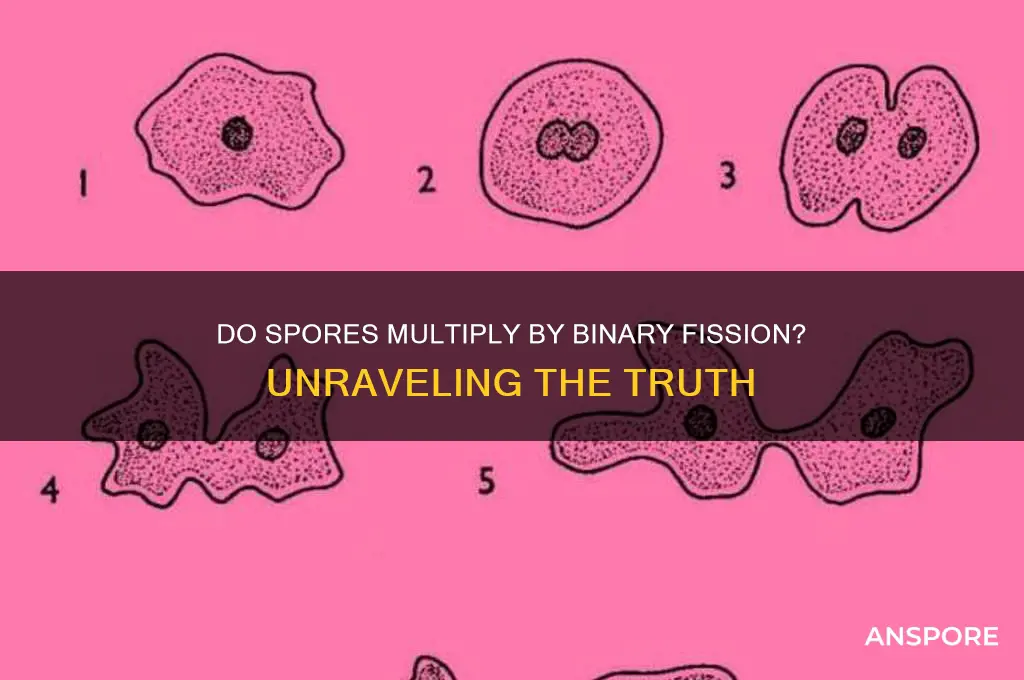

Spores, often associated with plants and fungi, are not typically known for multiplying through binary fission, a process more commonly attributed to prokaryotic cells like bacteria. However, certain spore-forming organisms, such as some bacteria and protozoa, do employ binary fission as a means of reproduction. This process involves a single spore dividing into two identical daughter spores, effectively doubling its genetic material. Unlike the complex life cycles of fungal or plant spores, which often involve alternation of generations, binary fission in spore-forming organisms is a straightforward, asexual method of replication.

To understand the binary fission process in spores, consider the steps involved. First, the spore’s genetic material, typically a single circular chromosome, replicates to produce an identical copy. Next, the cell elongates, and the replicated chromosomes migrate to opposite ends of the spore. A septum then forms at the center, dividing the spore into two compartments. Finally, the cell wall and membrane complete the separation, resulting in two genetically identical daughter spores. This process is highly efficient, allowing rapid population growth under favorable conditions. For example, *Bacillus subtilis*, a spore-forming bacterium, can complete binary fission in as little as 20 minutes under optimal conditions, though this timeframe varies depending on environmental factors like nutrient availability and temperature.

From a practical standpoint, understanding binary fission in spores has significant implications, particularly in fields like microbiology and biotechnology. For instance, in food preservation, knowing how spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* replicate through binary fission helps in developing effective sterilization techniques. High-temperature treatments, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, are commonly used to kill spores and prevent their multiplication. Similarly, in biotechnology, controlling binary fission in spores is crucial for producing bioactive compounds or enzymes on a large scale. Researchers often manipulate environmental conditions, such as pH and nutrient concentration, to optimize spore replication rates.

Comparatively, binary fission in spores differs from other forms of spore reproduction, such as budding or fragmentation, in its simplicity and speed. While budding involves the outgrowth of a new individual from the parent, and fragmentation requires the breaking of the parent into pieces, binary fission is a clean, symmetrical division. This efficiency makes it a favored mechanism for organisms needing to colonize new environments quickly. However, it also poses challenges, as the genetic uniformity of daughter spores can limit adaptability to changing conditions. For example, if a population of spores faces a new antibiotic, their identical genetic makeup means they either all survive or all perish, with no variation to ensure survival.

In conclusion, the binary fission process in spores is a remarkable mechanism of replication, characterized by the division of a single spore into two identical daughter spores with doubled genetic material. While not as widely recognized as other forms of spore reproduction, it plays a critical role in the life cycles of certain organisms. By studying this process, scientists can develop strategies to control spore-forming pathogens and harness their potential in biotechnology. Whether in the lab or in nature, binary fission in spores exemplifies the elegance and efficiency of microbial reproduction.

Can Flood Spores Wait? Understanding Their Survival and Dormancy Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Conditions for Fission: Requires favorable environment: nutrients, moisture, temperature, and stable conditions

Spores, those resilient survival structures of certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, do not multiply through binary fission themselves. Instead, they germinate under specific conditions to produce cells that then undergo binary fission. This process is not spontaneous but hinges on a precise environmental recipe: nutrients, moisture, temperature, and stability. Without these, spores remain dormant, biding their time until conditions align.

Consider the nutrient requirement as the fuel for growth. Spores need access to organic matter—carbon, nitrogen, and other essential elements—to synthesize the building blocks of new cells. For instance, bacterial spores like those of *Bacillus anthracis* require amino acids and sugars, often found in soil or decaying organic material. In laboratory settings, nutrient-rich media such as LB broth or agar plates are used to trigger germination. The concentration matters: too little, and germination stalls; too much, and osmotic stress can inhibit the process. Aim for a balanced medium with a carbon source (e.g., glucose at 1–2% concentration) and a nitrogen source (e.g., peptone at 1–2% concentration) for optimal results.

Moisture is equally critical, acting as both a medium for nutrient absorption and a catalyst for metabolic processes. Spores can absorb water through their semi-permeable coats, rehydrating their internal structures and activating enzymes necessary for growth. However, the moisture level must be just right. Too dry, and spores remain dormant; too wet, and they risk damage from excessive hydration or waterborne contaminants. For practical applications, such as cultivating fungal spores, maintain a relative humidity of 70–90% and ensure the substrate is moist but not waterlogged.

Temperature plays a dual role: it influences metabolic rates and determines whether spores remain dormant or activate. Most spores have an optimal germination temperature range, typically between 25°C and 37°C for bacterial spores and 20°C to 30°C for fungal spores. Deviations from this range can either slow germination or prevent it entirely. For example, *Clostridium botulinum* spores germinate best at 35°C, while *Aspergillus* spores thrive around 25°C. Use incubators or controlled environments to maintain these temperatures, especially in experimental or agricultural settings.

Finally, stability in the environment is non-negotiable. Spores are sensitive to sudden changes in pH, salinity, or physical disturbances, which can disrupt germination or kill the emerging cell. A stable pH range of 6.5 to 7.5 is ideal for most spores, as extreme acidity or alkalinity can denature enzymes. Similarly, avoid environments with high salinity or mechanical agitation, which can damage spore coats. In gardening, for instance, ensure soil pH is neutral and avoid over-tilling to create a stable habitat for spore germination.

In summary, while spores themselves do not multiply by binary fission, their ability to germinate and initiate this process relies on a finely tuned environment. By providing the right balance of nutrients, moisture, temperature, and stability, you can unlock their potential for growth. Whether in a lab, garden, or industrial setting, precision in these conditions is key to harnessing the power of spores.

Troubleshooting Origin Spore Code Redemption Issues: Quick Fixes and Solutions

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Vegetative Cells: Spores are dormant; binary fission occurs in active vegetative cells

Spores and vegetative cells represent two distinct phases in the life cycle of certain organisms, each with unique functions and mechanisms of survival. Spores are dormant structures, designed to withstand harsh environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemical exposure. This dormancy is a survival strategy, allowing the organism to persist in unfavorable conditions until resources become available again. In contrast, vegetative cells are metabolically active, engaging in growth, reproduction, and nutrient acquisition under optimal conditions. Understanding this dichotomy is crucial for fields like microbiology, agriculture, and medicine, where controlling these phases can prevent contamination or promote beneficial growth.

Binary fission, a form of asexual reproduction, is a hallmark of active vegetative cells. This process involves a single cell dividing into two identical daughter cells, driven by favorable conditions and abundant resources. For example, bacteria like *Escherichia coli* multiply rapidly through binary fission when nutrients are plentiful, doubling their population every 20 minutes under ideal conditions. Spores, however, do not multiply by binary fission. Instead, they remain in a quiescent state, conserving energy and resources until environmental cues signal a return to favorable conditions. This distinction highlights the specialized roles of spores and vegetative cells in ensuring the survival and propagation of the species.

To illustrate the practical implications, consider the food industry, where spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* pose significant risks. Spores can survive pasteurization temperatures (typically 63°C for 30 minutes), only to germinate into vegetative cells when conditions improve, leading to food spoilage or botulism. Preventing this requires more aggressive methods, such as sterilization at 121°C for 15 minutes, to destroy both spores and vegetative cells. This example underscores the importance of targeting the correct life stage when implementing control measures.

From a biological perspective, the transition from spore to vegetative cell is tightly regulated. Germination, the process by which a spore reactivates, requires specific triggers such as nutrients, moisture, and optimal temperature. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores germinate in the presence of L-valine and certain sugars, resuming metabolic activity and eventually undergoing binary fission. This transition is not merely a return to activity but a strategic response to environmental cues, ensuring that energy is expended only when survival and growth are feasible.

In summary, while vegetative cells thrive and multiply through binary fission under favorable conditions, spores remain dormant, biding their time until the environment supports their reactivation. This duality is a testament to the adaptability of certain organisms, offering insights into survival strategies and practical applications in industries ranging from healthcare to food safety. Recognizing the distinct roles and mechanisms of spores and vegetative cells enables more effective management and manipulation of microbial life cycles.

Disinfectants vs. Spores: Can Cleaning Agents Eliminate Resilient Microbial Spores?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role in Reproduction: Binary fission is asexual, rapidly increasing spore population under optimal conditions

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain organisms, do not themselves multiply by binary fission. This process is reserved for the vegetative, actively growing stages of bacteria and some single-celled organisms. However, understanding binary fission is crucial to grasping how spore-producing organisms rapidly increase their population under favorable conditions. Binary fission is a form of asexual reproduction where a single cell divides into two identical daughter cells, doubling the population with each cycle. This mechanism is highly efficient, allowing for exponential growth when resources are abundant and environmental conditions are optimal.

Consider the life cycle of spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus subtilis*. When nutrients are plentiful, these bacteria reproduce through binary fission, rapidly colonizing their environment. Each division takes as little as 20–30 minutes under ideal conditions (e.g., 37°C, pH 7, ample nutrients), enabling a single cell to generate millions of descendants within 10 hours. This explosive growth is essential for establishing dominance in competitive ecosystems. However, when conditions deteriorate—such as nutrient depletion or extreme temperatures—these bacteria enter a dormant spore state, halting reproduction until the environment improves.

The asexual nature of binary fission ensures genetic uniformity among offspring, which is both a strength and a limitation. Uniformity allows for rapid adaptation to stable environments but reduces the population’s ability to respond to sudden changes. For instance, if a new antibiotic is introduced, a genetically identical population may either all survive or all perish, depending on whether the parent cell carries resistance. This contrasts with sexual reproduction, which generates genetic diversity through recombination. Yet, for spore-forming organisms, binary fission’s speed and efficiency are prioritized during favorable phases, ensuring maximal resource exploitation before sporulation becomes necessary.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in industries like food preservation and medicine. For example, controlling temperature and nutrient availability can inhibit binary fission in foodborne pathogens like *Clostridium botulinum*, preventing spoilage. Conversely, optimizing conditions for beneficial bacteria in probiotics can enhance their population growth, improving product efficacy. Understanding the interplay between binary fission and sporulation also aids in developing antimicrobial strategies, as targeting the vegetative phase (when binary fission occurs) is more effective than attacking dormant spores, which are inherently resistant to many stressors.

In summary, while spores themselves do not multiply by binary fission, this process is pivotal in the reproductive strategy of spore-forming organisms. By rapidly increasing population size during optimal conditions, binary fission ensures these organisms can capitalize on resources before transitioning to the spore state for survival. This dual approach—exponential growth followed by dormancy—highlights the adaptability of such life cycles, offering insights for both scientific research and practical applications in fields ranging from microbiology to biotechnology.

Exploring Pteridophytes: Do They Have Spore Capsules or Not?

You may want to see also

Comparison to Sporulation: Sporulation forms spores; binary fission multiplies vegetative cells, not spores directly

Spores and vegetative cells represent distinct stages in the life cycles of certain microorganisms, each with unique mechanisms of reproduction. While sporulation is a specialized process that forms dormant, resilient spores, binary fission is a method of asexual reproduction that multiplies vegetative cells. Understanding these differences is crucial for fields like microbiology, medicine, and environmental science, where the behavior of these cells impacts survival, infection, and ecosystem dynamics.

Consider the process of sporulation in *Bacillus subtilis*, a well-studied bacterium. Under stress conditions like nutrient depletion, this organism initiates a complex developmental program. Over several hours, it asymmetrically divides to form a spore within the mother cell. This spore is not a product of binary fission but a highly specialized structure designed for long-term survival in harsh environments. In contrast, binary fission in *Escherichia coli* involves a vegetative cell replicating its DNA, dividing its cytoplasm, and splitting into two identical daughter cells, each capable of immediate growth. This rapid multiplication is ideal for exploiting favorable conditions but lacks the spore’s durability.

From a practical standpoint, distinguishing between these processes has significant implications. For instance, in food preservation, understanding that spores (not vegetative cells) survive high temperatures explains why sterilization requires prolonged heating (e.g., 121°C for 15 minutes in autoclaving). Conversely, disinfectants like bleach target vegetative cells, which are more susceptible to chemical disruption. In medicine, spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium difficile* require specific treatments, as their spores can persist in the gut and re-germinate, while antibiotics effectively target binary fission in actively growing bacteria.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both processes ensure survival, they serve different ecological roles. Sporulation is a long-term strategy, producing spores that can remain dormant for years, waiting for optimal conditions. Binary fission, however, is a short-term tactic, enabling rapid population growth in nutrient-rich environments. For example, in soil ecosystems, *Bacillus* spores persist through droughts, while *E. coli* thrives in transient nutrient surges. This duality highlights the adaptability of microorganisms to diverse environments.

In summary, sporulation and binary fission are distinct mechanisms with complementary functions. Sporulation forms spores as a survival strategy, while binary fission multiplies vegetative cells for immediate growth. Recognizing these differences allows for targeted interventions in industries like food safety, healthcare, and environmental management. Whether designing sterilization protocols or treating infections, understanding these processes ensures effective outcomes.

Do Spores Spark Growth? Unveiling the Science Behind Their Potential

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spores do not multiply by binary fission. Spores are reproductive structures produced by certain organisms, such as fungi, bacteria, and plants, and they typically germinate to form new individuals rather than multiplying through binary fission.

Binary fission is a form of asexual reproduction where a single organism divides into two identical daughter cells. It is primarily used by prokaryotes like bacteria and some single-celled organisms, not by spores.

Spores reproduce by germinating under favorable conditions, growing into a new organism. For example, fungal spores develop into hyphae, while bacterial spores (endospores) germinate into vegetative cells, which can then multiply by binary fission.

After germination, some spores (like bacterial endospores) produce vegetative cells that can multiply by binary fission. However, the spores themselves do not directly undergo binary fission.

![Shirayuri Koji [Aspergillus oryzae] Spores Gluten-Free Vegan - 10g/0.35oz](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61ntibcT8gL._AC_UL320_.jpg)