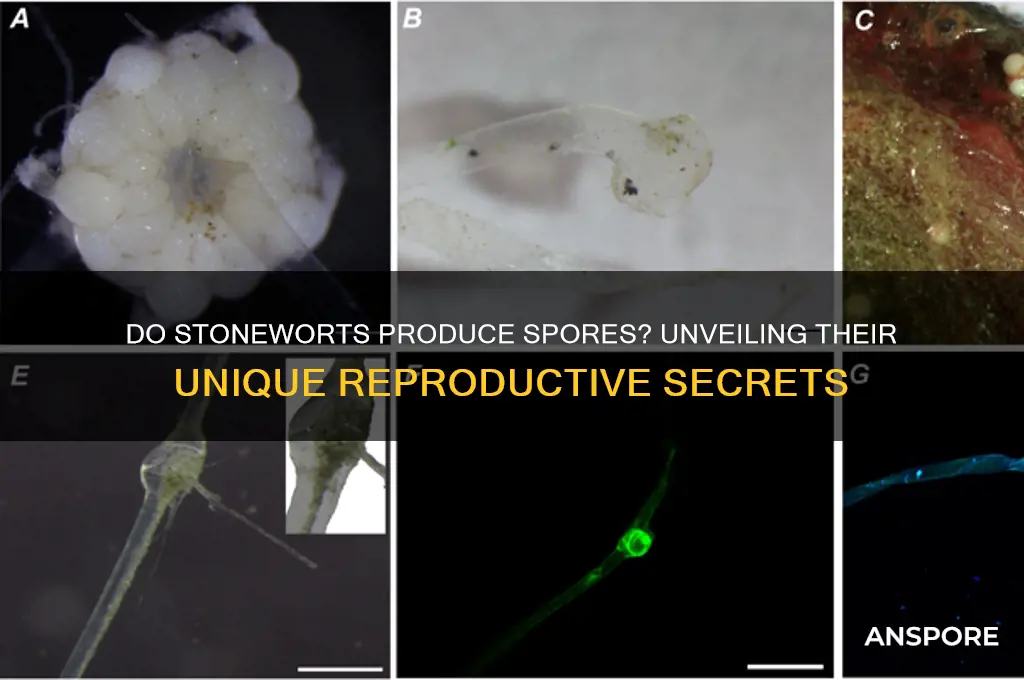

Stoneworts, also known as Charophytes, are a group of freshwater algae that resemble plants and are often mistaken for higher aquatic plants due to their complex structures. One of the most fascinating aspects of their life cycle is their method of reproduction, which includes the production of spores. Stoneworts are known to produce both asexual and sexual spores, with the latter being a key feature in their classification as part of the Charophyta division. Asexual spores, called *oospores*, are typically formed in response to unfavorable environmental conditions and serve as a means of survival. In contrast, sexual spores, such as *zygospores* and *tetraspores*, are produced during the sexual phase of their life cycle, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptation. This unique reproductive strategy highlights the evolutionary significance of stoneworts, bridging the gap between algae and land plants.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spores Production | Yes, stoneworts (Characeae) produce spores as part of their life cycle. |

| Types of Spores | 1. Oospores: Zygotic spores, formed through sexual reproduction. |

| 2. Aplanospores: Asexual spores, produced under unfavorable conditions. | |

| 3. Zoospores: Motile spores, rarely produced in some species. | |

| Location of Spore Formation | Oospores are formed within the oogonium; other spores in the sporangium. |

| Function of Spores | Serve as survival structures, aiding in dispersal and dormancy. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Spores are part of the alternation of generations in stoneworts. |

| Ecological Importance | Spores contribute to the species' resilience in aquatic environments. |

| Taxonomic Significance | Spore characteristics are used in classifying stonewort species. |

Explore related products

$15.13

What You'll Learn

- Sporangia Formation: Stoneworts develop sporangia, specialized structures where spores are produced and stored

- Spores Types: They produce two types: megaspores (female) and microspores (male) for reproduction

- Release Mechanism: Spores are released through sporangia rupture or decay, aiding dispersal

- Environmental Triggers: Sporulation is influenced by factors like light, temperature, and nutrient availability

- Survival Role: Spores act as dormant survival units, enduring harsh conditions until favorable growth returns

Sporangia Formation: Stoneworts develop sporangia, specialized structures where spores are produced and stored

Stoneworts, or Characeae, are unique freshwater algae that defy their simple appearance with a complex reproductive strategy. Central to this strategy is the formation of sporangia, specialized structures where spores are meticulously produced and stored. These sporangia are not merely containers; they are highly organized, multicellular organs that reflect the evolutionary sophistication of stoneworts. Unlike the simpler spore-producing mechanisms of some algae, stoneworts’ sporangia are embedded within their branching structures, ensuring protection and efficient dispersal in aquatic environments.

To understand sporangia formation, consider the developmental process. Stoneworts produce two types of sporangia: oospores (female) and microspores (male). The oogonium, a female reproductive organ, develops into a thick-walled oospore after fertilization, serving as a durable survival structure. Conversely, the antheridium, a male organ, releases microspores that are motile and seek out oogonia for fertilization. This sexual reproduction cycle is tightly regulated, with sporangia forming in response to environmental cues such as light, temperature, and nutrient availability. For instance, shorter daylight hours in late summer often trigger sporangia development, preparing the stoneworts for overwintering.

Practical observation of sporangia formation can be a rewarding endeavor for aquarists or botanists. To identify sporangia, examine mature stonewort plants under a low-power microscope (10x–40x magnification). Look for spherical or oval structures attached to the branches, often with a distinct texture or color. For those cultivating stoneworts, maintaining stable water conditions—pH 6.5–7.5, temperature 18–24°C, and moderate lighting—can encourage healthy sporangia development. Avoid sudden changes in water chemistry, as stress can inhibit reproductive processes.

Comparatively, stoneworts’ sporangia formation sets them apart from other aquatic plants. While many algae produce spores directly on their thalli, stoneworts invest energy in developing specialized organs, a trait more akin to higher plants. This distinction highlights their evolutionary position as a bridge between simple algae and complex land plants. For educators or hobbyists, this makes stoneworts an excellent subject for studying plant evolution and reproductive biology in a home or classroom setting.

In conclusion, sporangia formation in stoneworts is a fascinating example of nature’s ingenuity. By developing specialized structures for spore production and storage, stoneworts ensure their survival in dynamic freshwater ecosystems. Whether observed in the wild or cultivated in a controlled environment, understanding this process offers insights into both the biology of stoneworts and the broader principles of plant reproduction. With careful observation and proper care, anyone can witness this remarkable phenomenon firsthand.

Can Spores Contaminate Your Grow? Prevention and Solutions Explained

You may want to see also

Spores Types: They produce two types: megaspores (female) and microspores (male) for reproduction

Stoneworts, or Characeae, are unique freshwater algae that have evolved a sophisticated reproductive strategy centered around spore production. Among their reproductive adaptations, the most notable is the generation of two distinct spore types: megaspores and microspores. These spores are not merely reproductive units but are sexually dimorphic, with megaspores functioning as female gametangia and microspores as male gametangia. This division ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in varying aquatic environments.

To understand their reproductive process, consider the lifecycle stages. When conditions are favorable, stoneworts develop specialized structures called oogonia and antheridia. The oogonia produce a single, large megaspore, while the antheridia release numerous, smaller microspores. These microspores are motile, propelled by flagella, and seek out megaspores for fertilization. This mechanism is akin to the sperm-egg dynamic in higher plants, showcasing stoneworts’ evolutionary sophistication despite their algal classification.

Practical observation of these spores can be facilitated through microscopy. To examine megaspores, collect mature stonewort branches and gently crush them in a drop of water on a slide. Megaspores appear as large, spherical cells, often measuring 50–100 micrometers in diameter. Microspores, in contrast, are minuscule (2–5 micrometers) and require higher magnification to observe their flagellated structure. This hands-on approach not only aids in identification but also highlights the functional disparity between the two spore types.

From an ecological perspective, the production of megaspores and microspores serves as a survival strategy. Megaspores, being larger, store more nutrients, enabling them to withstand harsh conditions and germinate into new plants when resources are scarce. Microspores, though less resilient, compensate with sheer numbers and motility, increasing the likelihood of successful fertilization. This dual approach ensures stoneworts’ persistence in fluctuating freshwater habitats, from nutrient-rich ponds to oligotrophic lakes.

In conclusion, the production of megaspores and microspores by stoneworts is a testament to their reproductive ingenuity. By combining size disparity, motility, and environmental resilience, these spores exemplify nature’s efficiency in ensuring species continuity. Whether studied in a laboratory or observed in the wild, this reproductive mechanism offers valuable insights into the evolutionary strategies of aquatic plants.

Do Daisies Have Spores? Unveiling the Truth About Daisy Reproduction

You may want to see also

Release Mechanism: Spores are released through sporangia rupture or decay, aiding dispersal

Stoneworts, or Characeae, are unique freshwater algae known for their calcified cell walls and plant-like structures. Among their reproductive strategies, spore production is a key mechanism. Spores are housed within sporangia, specialized structures that protect and prepare them for dispersal. The release of these spores is not a passive process but a dynamic event triggered by sporangia rupture or decay, ensuring efficient distribution in aquatic environments.

The rupture of sporangia is a mechanical process often induced by environmental factors such as water currents, temperature changes, or physical stress. As the sporangia walls weaken, they eventually break open, releasing spores into the surrounding water. This method is particularly effective in fast-moving streams or turbulent waters, where spores can be carried over greater distances. Decay, on the other hand, is a slower, biological process where the sporangia degrade over time, gradually releasing spores. This method is more common in stagnant or slow-moving waters, where spores settle closer to the parent plant but still achieve dispersal through diffusion and sediment movement.

Understanding this release mechanism is crucial for ecologists and aquarists alike. For instance, in aquarium settings, mimicking natural water flow patterns can enhance spore dispersal, promoting the growth of stoneworts in controlled environments. In natural habitats, this mechanism ensures genetic diversity by spreading spores across diverse areas, increasing the species' resilience to environmental changes. Practical tips include monitoring water flow rates and ensuring substrate stability to optimize spore release and colonization.

Comparatively, the spore release mechanism of stoneworts contrasts with that of terrestrial plants, which often rely on wind, animals, or explosive mechanisms for dispersal. Stoneworts' aquatic environment necessitates a simpler yet effective strategy, leveraging water movement and natural decay. This adaptation highlights their evolutionary success in freshwater ecosystems, where resources and conditions are vastly different from those on land.

In conclusion, the release of spores through sporangia rupture or decay is a finely tuned process that maximizes dispersal in aquatic habitats. By studying this mechanism, we gain insights into stoneworts' reproductive strategies and their ecological role. Whether in natural waters or aquariums, understanding and replicating these conditions can foster healthier stonewort populations, contributing to biodiversity and ecosystem stability.

Can Mold Spores Get on Clothes? Understanding Risks and Prevention

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers: Sporulation is influenced by factors like light, temperature, and nutrient availability

Stoneworts, or charophyte algae, are known for their complex life cycles, which include the production of spores. Sporulation in these organisms is not a random process but is finely tuned to environmental cues. Among the most critical triggers are light, temperature, and nutrient availability, each playing a distinct role in signaling the optimal conditions for spore development. Understanding these factors provides insight into how stoneworts adapt to their aquatic habitats and ensures their survival across seasons.

Light acts as a primary environmental cue for sporulation in stoneworts, with intensity and duration directly influencing the timing of spore production. Studies have shown that stoneworts exposed to higher light levels, particularly in the blue spectrum (400–500 nm), exhibit accelerated sporulation. For instance, *Chara vulgaris*, a common stonewort species, initiates spore formation under 12–16 hours of daily light exposure, mimicking natural daylight cycles. However, excessive light can inhibit sporulation, as it may lead to photoinhibition or oxidative stress. Aquarists and researchers should maintain light levels between 50–100 μmol/m²/s for optimal spore development, adjusting based on the species’ specific requirements.

Temperature is another critical factor, with stoneworts typically favoring cooler, stable conditions for sporulation. Most species thrive in water temperatures between 15–22°C, with deviations outside this range delaying or halting spore production. For example, *Nitella translucens* shows reduced sporulation at temperatures above 25°C, while cooler temperatures below 12°C extend the developmental period. Seasonal changes in temperature often correlate with sporulation cycles, as stoneworts prepare for winter dormancy or spring regeneration. Monitoring water temperature and maintaining consistency within the optimal range is essential for cultivating healthy stonewort populations.

Nutrient availability, particularly phosphorus and nitrogen, significantly impacts sporulation in stoneworts. These nutrients are essential for the synthesis of nucleic acids and proteins required for spore development. In nutrient-rich environments, stoneworts often produce larger quantities of spores, but excessive nutrients can lead to algal blooms, reducing light penetration and oxygen levels. Conversely, nutrient-poor conditions may limit spore viability. Aquarists should aim for a balanced nutrient profile, with phosphorus levels around 0.05–0.1 mg/L and nitrogen levels between 0.5–1.0 mg/L, to support healthy sporulation without triggering adverse effects.

In practical terms, manipulating these environmental triggers can enhance stonewort cultivation and conservation efforts. For instance, in controlled environments like aquariums or research labs, adjusting light cycles, temperature, and nutrient levels can synchronize sporulation, facilitating study and propagation. In natural habitats, understanding these triggers helps predict how stoneworts respond to climate change or pollution, which alter light availability, water temperature, and nutrient balance. By addressing these factors, conservationists can develop strategies to protect stonewort populations, ensuring their role in aquatic ecosystems remains intact.

Do Spore Cleaners Work? Unveiling the Truth Behind Their Effectiveness

You may want to see also

Survival Role: Spores act as dormant survival units, enduring harsh conditions until favorable growth returns

Stoneworts, or Characeae, are a fascinating group of freshwater algae that have evolved unique survival strategies. Among these, their ability to produce spores stands out as a critical mechanism for enduring environmental challenges. Spores, in essence, are nature’s time capsules—microscopic, resilient structures that allow stoneworts to pause their life cycle until conditions improve. This dormancy is not merely a passive state but a highly specialized adaptation, ensuring the species’ continuity in unpredictable aquatic ecosystems.

Consider the lifecycle of stoneworts: when faced with threats like drought, extreme temperatures, or nutrient depletion, they shift from active growth to spore production. These spores, often encased in protective layers, can withstand desiccation, freezing temperatures, and even chemical stressors. For instance, *Chara vulgaris*, a common stonewort species, produces oospores that remain viable in sediment for years, waiting for the return of water and nutrients. This survival strategy is particularly crucial in ephemeral habitats like seasonal ponds or fluctuating riverbeds, where stability is rare.

The production of spores is not just a reactive measure but a proactive one. Stoneworts invest energy in spore formation during favorable periods, ensuring a reservoir of genetic material for future generations. This foresight is akin to saving resources for lean times, a principle echoed in both biology and human economics. For hobbyists cultivating stoneworts in aquariums, understanding this process is key. Maintaining stable water conditions and avoiding sudden environmental shifts can reduce unnecessary spore production, allowing the plant to focus on growth and aesthetic appeal.

Comparatively, stonewort spores share similarities with the seeds of terrestrial plants, yet they are uniquely adapted to aquatic challenges. Unlike seeds, which often require specific triggers like fire or scarification to germinate, stonewort spores activate primarily in response to water availability and nutrient levels. This simplicity in activation mechanisms reflects their environment—water, a dynamic medium where cues are often less complex than on land. For conservationists, this knowledge is invaluable, as it informs strategies for restoring stonewort populations in degraded habitats.

In practical terms, anyone studying or managing stoneworts should monitor environmental stressors that trigger spore production. For example, in aquaculture settings, maintaining a consistent water temperature between 18–24°C and ensuring adequate light (10–12 hours daily) can discourage premature spore formation. Additionally, periodic sediment testing can reveal dormant spores, indicating past environmental stress. By addressing these factors, one can promote healthy, active growth while preserving the species’ ability to survive long-term challenges. This dual focus—on immediate vitality and future resilience—is the essence of stoneworts’ spore-driven survival strategy.

Breathing Spores and Anaphylaxis: Uncovering the Hidden Allergic Reaction Risk

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, stoneworts (Characeae) produce spores as part of their reproductive cycle.

Stoneworts produce two types of spores: oogonia (female spores) and antheridia (male spores), which are involved in sexual reproduction.

Stonewort spores are typically dispersed through water currents, ensuring their spread to new habitats for colonization.

![EidolonGreen [China Medicinal Herb] Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca/Leonurus Japonicus/Yimucao/益母草/익모초) Dried Bulk Herb 3 Oz (88 g)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61Oe0GLj0kS._AC_UL320_.jpg)