Vascular plants, which include ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms, exhibit diverse reproductive strategies, but not all of them reproduce using spores. While non-vascular plants like mosses and liverworts rely on spores for reproduction, most vascular plants have evolved more advanced methods. Ferns, for instance, do produce spores as part of their life cycle, alternating between a sporophyte (spore-producing) and gametophyte (gamete-producing) generation. However, seed plants—gymnosperms (e.g., conifers) and angiosperms (flowering plants)—reproduce via seeds, which contain an embryo, nutrients, and protective structures, eliminating the need for a free-living gametophyte stage. Thus, while some vascular plants use spores, others have developed more complex reproductive mechanisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Vascular plants primarily reproduce through seeds, not spores, in their life cycle. |

| Spores in Vascular Plants | Some vascular plants (e.g., ferns, horsetails, and lycophytes) produce spores as part of their alternation of generations, but this is not the primary method of reproduction. |

| Seed Production | Most vascular plants (e.g., angiosperms and gymnosperms) produce seeds, which contain an embryo, stored food, and a protective coat. |

| Alternation of Generations | Vascular plants exhibit alternation of generations, with a sporophyte (diploid) phase that produces spores and a gametophyte (haploid) phase that produces gametes. |

| Spore Function | Spores in vascular plants are typically produced by the sporophyte and develop into gametophytes, which then produce eggs and sperm for sexual reproduction. |

| Examples of Spore-Producing Vascular Plants | Ferns, horsetails, clubmosses, and whisk ferns. |

| Examples of Seed-Producing Vascular Plants | Flowering plants (angiosperms) and conifers (gymnosperms). |

| Dominant Phase | In seed-producing vascular plants, the sporophyte phase is dominant, while in spore-producing vascular plants, both phases are often free-living but the sporophyte is usually more prominent. |

| Adaptations | Seed reproduction provides vascular plants with advantages such as protection, nutrient storage, and delayed germination, contributing to their success in diverse environments. |

| Evolutionary Significance | The evolution of seeds in vascular plants marked a major milestone, allowing them to colonize drier habitats and become the dominant form of plant life on Earth. |

Explore related products

$142.31 $214

What You'll Learn

Spore Formation in Vascular Plants

Vascular plants, including ferns, lycophytes, and horsetails, reproduce via spores—a method distinct from the seed-based reproduction of gymnosperms and angiosperms. Unlike seeds, spores are unicellular and lack stored nutrients, relying on favorable conditions to germinate into gametophytes. This process, known as alternation of generations, involves a diploid sporophyte phase producing spores and a haploid gametophyte phase producing gametes. Understanding spore formation is key to grasping the life cycle of these plants, which dominate in environments where water is abundant for their reproductive needs.

Spore formation begins in specialized structures called sporangia, typically located on the underside of leaves or within cones. In ferns, for example, sporangia cluster into sori, protected by a thin membrane called the indusium. Within each sporangium, diploid sporocytes undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores. The number of spores per sporangium varies by species; ferns often produce 64 or 128 spores per sporangium. Environmental cues, such as humidity and temperature, trigger spore release, ensuring dispersal during optimal conditions.

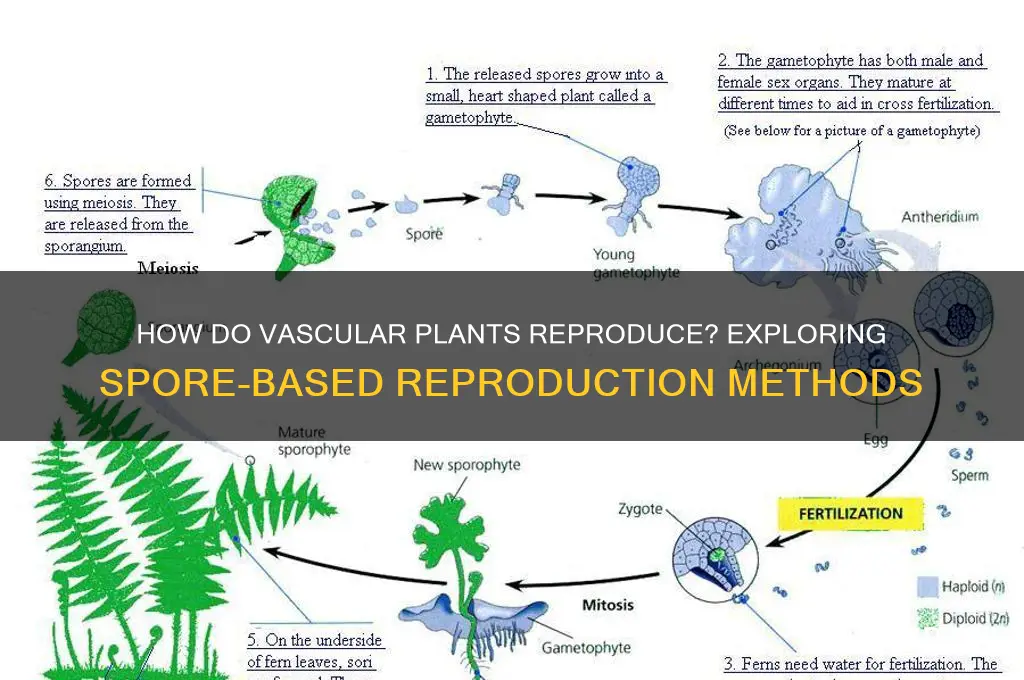

The lifecycle’s success hinges on spore dispersal, a process driven by wind, water, or animals. Fern spores, for instance, are lightweight and equipped with elaters—coiled structures that aid in propulsion when dry. Once dispersed, spores require moisture to germinate, developing into heart-shaped gametophytes (prothalli) that house male and female reproductive organs. Fertilization occurs when sperm, released from antheridia, swim to archegonia using water as a medium, resulting in a zygote that grows into a new sporophyte.

Practical applications of spore formation knowledge include horticulture and conservation. Gardeners cultivating ferns must mimic natural conditions by maintaining high humidity and providing indirect light to encourage spore germination. In conservation, understanding spore dispersal helps protect endangered species like the whisk fern (*Psilotum nudum*), which relies on specific microhabitats for spore survival. For educators, demonstrating spore formation under a microscope offers a tangible way to teach plant biology, revealing the intricate structures that sustain these ancient lineages.

Comparatively, spore reproduction contrasts sharply with seed reproduction in its vulnerability to environmental factors. While seeds contain embryos and nutrient reserves, spores depend entirely on external conditions for survival. This trade-off highlights the evolutionary adaptations of vascular plants, with spore-reproducing species thriving in stable, moist environments and seed plants dominating diverse ecosystems. By studying spore formation, we gain insight into the resilience and limitations of these reproductive strategies, shaping our approach to botany, ecology, and conservation efforts.

Yeast Spore Germination: Unveiling the Intricate Process of Awakening

You may want to see also

Alternation of Generations Process

Vascular plants, such as ferns, clubmosses, and horsetails, do indeed reproduce with spores, a process deeply intertwined with the alternation of generations. This life cycle is a fascinating dance between two distinct phases: the sporophyte (diploid) and the gametophyte (haploid). Each phase is not just a step but a fully functional organism, showcasing nature’s ingenuity in ensuring survival and diversity.

Consider the sporophyte generation, the phase most commonly recognized as the "plant." This green, photosynthetic organism produces spores in structures like sporangia. For example, in ferns, these spores are released into the environment, often carried by wind or water. Each spore is a single cell with a haploid chromosome set, capable of growing into a gametophyte under favorable conditions. This phase is critical for dispersal and colonization, allowing vascular plants to thrive in diverse habitats, from moist forests to rocky outcrops.

The gametophyte generation, though smaller and less conspicuous, is equally vital. It develops from a germinated spore and is typically a small, heart-shaped structure in ferns. This phase is responsible for sexual reproduction, producing gametes (sperm and eggs). The gametophyte is often dependent on moisture for sperm to swim to the egg, a limitation that ties many vascular plants to humid environments. Once fertilization occurs, a new sporophyte begins to grow, completing the cycle.

Practical observation of this process can be enlightening. For instance, if you’re cultivating ferns, ensure the soil remains consistently moist to support gametophyte development. Collecting and sowing spores requires patience, as they can take weeks to germinate. For educational purposes, compare the gametophytes of different vascular plants under a microscope to highlight their diversity despite their shared role in the life cycle.

In essence, the alternation of generations is not just a biological mechanism but a strategic adaptation. It balances the stability of the sporophyte with the reproductive agility of the gametophyte, ensuring vascular plants can thrive across ecosystems. Understanding this process not only deepens appreciation for plant biology but also informs conservation and cultivation efforts, making it a cornerstone of botanical study.

Can Mold Spores Penetrate Plastic Bags? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Role of Sporophytes and Gametophytes

Vascular plants, such as ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms, exhibit a unique life cycle characterized by the alternation of generations, where both sporophytes and gametophytes play critical roles in reproduction. The sporophyte generation, which is the dominant phase in most vascular plants, produces spores through a process called sporogenesis. These spores are haploid cells that develop into the gametophyte generation, a smaller, less conspicuous phase. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, as it involves both asexual (spore production) and sexual (gamete fusion) reproductive mechanisms.

Consider the fern as a classic example. The large, leafy fern plant you see is the sporophyte. On the underside of its fronds, it develops sporangia, structures that produce and release spores. Each spore, once dispersed, germinates into a tiny, heart-shaped gametophyte called a prothallus. This prothallus is short-lived but crucial, as it houses the male and female reproductive organs. When conditions are moist, sperm from the antheridia swim to the archegonia to fertilize the egg, resulting in a new sporophyte. This cycle highlights the interdependence of the two generations, with the sporophyte relying on the gametophyte for sexual reproduction and vice versa.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this cycle is essential for horticulture and conservation. For instance, propagating ferns from spores requires mimicking the gametophyte stage. Spores are sown on a sterile medium, kept humid, and provided with indirect light to encourage prothallus growth. Once mature, the prothalli will produce sporophytes under the right conditions. This method is not only cost-effective but also preserves genetic diversity, making it valuable for restoring endangered plant populations.

Comparatively, gymnosperms and angiosperms show reduced gametophytes, yet their roles remain vital. In gymnosperms like pines, the male gametophyte is the pollen grain, and the female gametophyte is retained within the ovule. Angiosperms take this reduction further, with the male gametophyte consisting of just three cells (the pollen tube and two sperm) and the female gametophyte (the embryo sac) embedded in the ovule. Despite their diminutive size, these gametophytes ensure the continuity of the species by facilitating fertilization.

In conclusion, the sporophyte and gametophyte generations are not mere stages in the life cycle of vascular plants but are integral to their reproductive success. The sporophyte’s role in spore production and the gametophyte’s function in sexual reproduction create a balanced system that has endured for millions of years. By studying and applying this knowledge, we can better cultivate, conserve, and appreciate the diversity of vascular plants.

Can You Play Spore on Xbox? Compatibility and Alternatives Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Types of Spores in Vascular Plants

Vascular plants, a diverse group including ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms, employ spores as a fundamental part of their life cycle. Unlike seeds, spores are unicellular and more primitive, yet they play a crucial role in the reproduction and dispersal of these plants. The types of spores produced by vascular plants vary significantly, each adapted to specific environmental conditions and reproductive strategies. Understanding these spore types not only sheds light on plant evolution but also aids in conservation and horticulture.

Analytical Perspective: Among vascular plants, ferns and their relatives (pteridophytes) produce two distinct types of spores: megaspores and microspores. Megaspores, larger in size, develop into female gametophytes, while microspores, smaller, give rise to male gametophytes. This dimorphism ensures sexual reproduction through the fusion of gametes. In contrast, seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms) have evolved beyond spore-dependent reproduction, yet their ancestors relied on similar mechanisms. For instance, pollen grains in gymnosperms, though not spores, share developmental similarities with microspores, highlighting an evolutionary link.

Instructive Approach: To identify spore types in vascular plants, examine their size, shape, and wall structure under a microscope. Fern spores, for example, are typically 20–50 micrometers in diameter, with intricate patterns on their walls that aid in identification. Gymnosperms like cycads produce larger megaspores (up to 500 micrometers) and smaller microspores, which can be distinguished by their size differential. Practical tip: Use a spore stain like cotton blue to enhance visibility under magnification. This technique is essential for botanists and hobbyists studying plant reproduction.

Comparative Insight: While all vascular plants share a spore-based reproductive phase, the transition to seed production in gymnosperms and angiosperms marks a significant evolutionary advancement. Seeds encapsulate the embryo and provide nutrients, reducing reliance on water for reproduction. However, spores remain advantageous in certain environments. Ferns, for instance, thrive in moist, shaded habitats where spores can disperse easily and germinate without desiccation. In contrast, desert-dwelling gymnosperms like pines rely on wind-dispersed pollen (derived from microspores) to overcome arid conditions.

Descriptive Detail: The diversity of spores in vascular plants is a testament to their adaptability. Homosporous plants, such as most ferns, produce a single spore type that develops into bisexual gametophytes. Heterosporous plants, including some ferns and all seed plants, produce megaspores and microspores, a trait linked to increased reproductive efficiency. For example, the water fern *Salvinia* exhibits heterosporous reproduction, with megaspores growing into female gametophytes that retain the egg, ensuring fertilization even in aquatic environments. This specialization underscores the evolutionary success of spore diversity in vascular plants.

Can Mange Spores Infect Humans? Understanding the Risks and Facts

You may want to see also

Environmental Factors Affecting Spore Reproduction

Vascular plants, such as ferns and lycophytes, rely on spores for reproduction, a process highly sensitive to environmental conditions. These microscopic units of life are dispersed into the air, water, or soil, where they germinate under favorable conditions. However, not all spores successfully develop into new plants. Environmental factors play a critical role in determining spore viability, dispersal, and germination, ultimately shaping the reproductive success of these species.

Humidity and Moisture: The Lifeline of Spore Germination

Spores require moisture to activate and initiate growth. In environments with low humidity, spores may remain dormant or desiccate, rendering them non-viable. For instance, fern spores need a thin film of water to absorb nutrients and begin cell division. In arid regions, spore reproduction is significantly hindered unless localized microhabitats, like shaded crevices or near water bodies, provide the necessary moisture. Practical tip: Gardeners cultivating spore-reproducing plants should maintain a humidity level of 60–80% and mist soil regularly to mimic natural conditions.

Temperature: A Delicate Balance for Spore Development

Temperature fluctuations directly impact spore metabolism and germination rates. Most vascular plant spores thrive in moderate temperatures ranging from 15°C to 25°C (59°F to 77°F). Extreme heat can denature enzymes essential for spore growth, while cold temperatures slow metabolic processes, delaying germination. For example, lycophyte spores exposed to temperatures below 10°C may remain dormant for extended periods. Caution: Avoid placing spore-bearing plants near heat sources or in unheated outdoor areas during winter to prevent reproductive failure.

Light Exposure: A Double-Edged Sword

Light influences spore dispersal and germination, but its effects vary by species. Some spores require light to trigger germination, while others are inhibited by it. For instance, certain fern species need red light to break dormancy, whereas others may germinate in darkness. Light also affects spore dispersal; wind-dispersed spores are more likely to travel in open, sunlit areas. Comparative analysis: Plants in dense forests may produce larger spores to compensate for reduced light availability, while those in open habitats often rely on smaller, more numerous spores for efficient dispersal.

Soil Composition: The Foundation of Spore Success

The chemical and physical properties of soil significantly impact spore germination and survival. Spores require a substrate rich in organic matter and with a pH between 5.5 and 7.0 for optimal growth. Acidic or alkaline soils can impair nutrient uptake, stunting development. For example, clubmoss spores thrive in well-drained, slightly acidic soil with a pH of 6.0. Instruction: Test soil pH before planting spore-reproducing species and amend with compost or sulfur to achieve the ideal range.

Wind and Water: Agents of Spore Dispersal

Environmental forces like wind and water are crucial for spore dispersal, ensuring genetic diversity and colonization of new habitats. Wind-dispersed spores are often lightweight and produced in large quantities, while water-dispersed spores may have thicker walls for buoyancy. However, excessive wind or water flow can scatter spores into unsuitable environments, reducing germination rates. Takeaway: When cultivating vascular plants, consider placement in areas with natural airflow or near water sources to enhance spore dispersal while protecting against extreme conditions.

By understanding and manipulating these environmental factors, gardeners, ecologists, and conservationists can optimize the reproductive success of spore-bearing vascular plants, ensuring their survival in diverse ecosystems.

Troubleshooting Spore Login Issues: Quick Fixes to Get Back in the Game

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, some vascular plants, such as ferns and lycophytes, reproduce via spores as part of their life cycle.

Vascular plants that reproduce with spores, like ferns, typically have an alternation of generations, with a dominant gametophyte or sporophyte phase, while seed-producing plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms) rely on seeds for reproduction and have a reduced gametophyte phase.

No, not all vascular plants reproduce with spores. Seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms) reproduce using seeds, while only certain groups like ferns, horsetails, and clubmosses use spores for reproduction.