The question of whether a spore needs to have a strong coat is central to understanding its survival and dispersal mechanisms in diverse environments. Spores, as dormant, resilient structures produced by various organisms such as fungi, plants, and bacteria, rely on their coats for protection against harsh conditions such as desiccation, UV radiation, and predation. A strong coat enhances a spore's longevity, enabling it to withstand extreme temperatures, chemical stressors, and physical damage, thereby increasing its chances of germination when favorable conditions arise. However, the necessity of a robust coat varies depending on the organism's ecological niche and life cycle, as some spores may prioritize rapid dispersal over long-term durability. Thus, the strength of a spore's coat is a critical adaptation that balances survival and reproductive success in its specific environment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Protection from Environmental Stress | A strong spore coat provides resistance to desiccation, UV radiation, extreme temperatures, and chemicals, ensuring long-term survival in harsh conditions. |

| Mechanical Strength | The coat offers structural integrity, protecting the spore from physical damage during dispersal and environmental exposure. |

| Dormancy Maintenance | A robust coat helps maintain spore dormancy by preventing premature germination and protecting against enzymatic degradation. |

| Hydrophobicity | The spore coat is often hydrophobic, reducing water uptake and preventing premature activation in unfavorable conditions. |

| Chemical Composition | Composed of proteins, peptides, and complex polymers like sporopollenin, which contribute to its strength and durability. |

| Species-Specific Variation | Coat thickness and composition vary among species, reflecting adaptations to specific environmental challenges. |

| Role in Pathogenicity | In pathogens, a strong coat aids in evading host immune responses and surviving within the host environment. |

| Dispersal Efficiency | A durable coat enhances spore dispersal by protecting against abrasion and predation during transport. |

| Longevity | Strong coats enable spores to remain viable for extended periods, ranging from years to millennia, in soil, water, or air. |

| Germination Control | The coat regulates germination by restricting access to nutrients and signals until conditions are favorable. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Coat thickness and spore survival

Spore coat thickness is a critical factor in determining survival rates under harsh conditions. Thicker coats provide enhanced protection against desiccation, UV radiation, and chemical stressors, acting as a barrier that shields the spore’s genetic material. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores with thicker coats exhibit up to 10-fold greater resistance to hydrogen peroxide compared to thinner-coated variants. This protective mechanism is particularly vital in extreme environments, such as arid deserts or outer space, where spores must endure prolonged exposure to lethal agents.

To optimize spore survival, consider the following practical steps: first, assess the environmental challenges the spores will face. If desiccation is the primary threat, select or engineer strains with coats enriched in dipicolinic acid, a compound that stabilizes the spore core during dehydration. Second, for UV protection, ensure the coat contains pigments like carotenoids, which absorb harmful wavelengths. Third, apply a thin layer of calcium-rich minerals to the coat surface, as calcium ions strengthen the coat’s structural integrity. These measures can significantly extend spore viability, especially in applications like soil remediation or long-term food preservation.

A comparative analysis reveals that coat thickness alone is not the sole determinant of spore survival. The composition and architecture of the coat layers also play pivotal roles. For example, the outer crust of *Clostridium botulinum* spores contains keratin-like proteins that resist enzymatic degradation, while the inner layer of *Deinococcus radiodurans* spores incorporates DNA repair enzymes. Thus, while thickness provides a physical barrier, the coat’s biochemical properties are equally essential for withstanding specific stressors. This duality underscores the need for a holistic approach when engineering spores for industrial or medical use.

From a persuasive standpoint, investing in research to manipulate coat thickness and composition could revolutionize biotechnology. Thicker, more resilient spores could enhance the shelf life of probiotics, improve vaccine stability without refrigeration, and enable the development of bioindicators for environmental monitoring. For instance, spores engineered with thicker coats could survive the harsh conditions of Mars, aiding in astrobiological research. By prioritizing coat thickness as a design parameter, scientists can unlock new applications for spores across agriculture, healthcare, and space exploration.

Finally, a cautionary note: while thicker coats enhance survival, they may also impede germination efficiency. A balance must be struck to ensure spores remain dormant until optimal conditions trigger revival. Over-engineering coat thickness could lead to energy-intensive germination processes, reducing the spore’s utility in time-sensitive applications. Therefore, when modifying coat thickness, pair it with mechanisms that facilitate controlled germination, such as incorporating germinant receptors or using osmotic triggers. This ensures that the enhanced survival benefits do not come at the cost of functionality.

Stun Spore vs. Electric Types: Does It Work in Pokémon Battles?

You may want to see also

Environmental stress resistance mechanisms

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, face extreme environmental challenges—desiccation, UV radiation, and temperature fluctuations. Their ability to endure these stresses hinges on the strength and composition of their protective coat. This outer layer, often likened to a suit of armor, is not merely a passive barrier but a dynamic system engineered to resist environmental assaults. For instance, bacterial endospores possess a multilayered coat that includes keratin-like proteins, providing rigidity and resistance to enzymes and chemicals. Without such a robust coat, spores would succumb to environmental stresses, failing to fulfill their evolutionary purpose of long-term survival.

Consider the instructive case of *Bacillus subtilis* spores, which owe their durability to a coat composed of over 70 proteins. These proteins are strategically arranged to form a porous yet resilient structure that blocks harmful molecules while allowing essential nutrients to pass. The coat’s assembly is a precise, stepwise process, with each layer contributing unique protective properties. For example, the outer crust layer provides resistance to heat and desiccation, while the inner layers protect against UV radiation and oxidative damage. Researchers have found that altering coat protein composition—such as increasing the expression of CotH proteins—enhances spore resistance to ethanol, a stressor relevant in industrial applications. This highlights the coat’s role as a customizable shield, tailored to specific environmental threats.

A persuasive argument for the necessity of a strong spore coat lies in its role as a determinant of survival in extreme habitats. Take *Deinococcus radiodurans*, a bacterium renowned for its resistance to ionizing radiation. While its DNA repair mechanisms are well-studied, its spore-like structures also feature a robust coat that shields genetic material from radiation-induced damage. Similarly, fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus* species rely on melanin-pigmented coats to absorb UV radiation, preventing DNA damage. Without these specialized coats, spores would be vulnerable to environmental stresses, limiting their dispersal and survival in harsh ecosystems. This underscores the coat’s evolutionary significance as a non-negotiable feature for spore resilience.

To illustrate the practical implications, imagine a scenario where spores are used in agricultural biocontrol agents or probiotics. For such applications, spores must withstand manufacturing processes, shelf storage, and environmental exposure post-application. Here, the coat’s strength becomes a critical factor. Studies show that spores with enhanced coat proteins, such as those overexpressing the SapA protein in *Bacillus thuringiensis*, exhibit increased tolerance to heat and desiccation, extending their viability in field conditions. For optimal results, manufacturers can employ genetic engineering to bolster coat proteins or apply exogenous protectants like trehalose during spore formulation. Such strategies ensure spores remain functional under stress, maximizing their utility in real-world applications.

In conclusion, the spore coat is not just a protective layer but a sophisticated environmental stress resistance mechanism. Its strength and composition directly correlate with a spore’s ability to withstand extreme conditions, from industrial processes to natural habitats. By understanding and manipulating coat properties, scientists can enhance spore resilience, unlocking their potential in biotechnology, agriculture, and beyond. Whether through genetic modification or protective formulations, investing in a stronger coat is essential for harnessing the full power of spores in challenging environments.

Mold Spores and Vertigo: Unraveling the Hidden Connection to Dizziness

You may want to see also

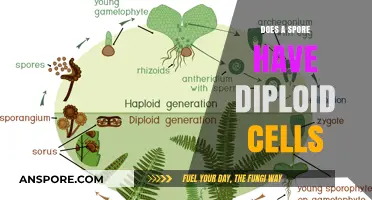

Role in dormancy and longevity

Spores, the resilient survival structures of various organisms, owe their longevity to a critical feature: the spore coat. This protective layer is not merely a passive barrier but a dynamic interface that regulates dormancy and ensures survival across harsh conditions. Composed of complex polymers like sporopollenin, the coat’s strength and composition directly influence a spore’s ability to withstand desiccation, UV radiation, and chemical stressors. For instance, bacterial endospores, with their multilayered coats, can persist for centuries, while fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus* rely on melanin-rich coats to endure extreme environments. Without a robust coat, spores would succumb to environmental assaults, rendering dormancy a fleeting state rather than a long-term strategy.

To understand the coat’s role in dormancy, consider its function as a gatekeeper of metabolic activity. During sporulation, the coat thickens and hardens, sealing the spore’s interior from external stimuli. This process is akin to placing the spore in a state of suspended animation, where metabolic processes are minimized to conserve energy. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* spores reduce their water content to as low as 20% of their dry weight, a feat made possible by the coat’s impermeability. Practical applications of this mechanism are seen in food preservation, where spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* are targeted by heat treatments designed to breach their coats and prevent germination. Strengthening the coat, therefore, is not just a defensive measure but a strategic adaptation for prolonged survival.

A comparative analysis of spore coats across species reveals their evolutionary ingenuity. Plant spores, such as those of ferns, have coats with intricate sculpturing that aids in dispersal and protection. In contrast, fungal spores often incorporate pigments like melanin, which provide resistance to UV radiation and oxidative stress. This diversity underscores the coat’s role as a tailored solution to specific environmental challenges. For researchers and industries, understanding these variations offers insights into developing biomimetic materials or enhancing spore-based technologies, such as microbial pesticides or probiotics. A strong coat is not a one-size-fits-all feature but a customized shield that defines a spore’s ecological niche.

Finally, the longevity of spores is a testament to the coat’s dual role as protector and regulator. Studies show that spores with compromised coats exhibit reduced viability over time, even under controlled conditions. For instance, mutations in coat protein genes in *Bacillus* spores lead to rapid degradation when exposed to heat or chemicals. Conversely, spores with enhanced coats, such as those engineered for increased sporopollenin thickness, demonstrate extended survival in soil and water. Practical tips for leveraging this knowledge include optimizing storage conditions for spore-based products—maintaining low humidity and stable temperatures to preserve coat integrity. Whether in nature or industry, the strength of the spore coat is non-negotiable for ensuring dormancy and longevity.

Mastering Morel Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Planting Spores

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact on germination efficiency

The strength of a spore's coat directly influences its germination efficiency, acting as a critical determinant of survival and propagation. A robust coat protects the spore's genetic material from environmental stressors such as desiccation, UV radiation, and enzymatic degradation. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores with intact, thick coats exhibit germination rates of up to 95% under optimal conditions, whereas spores with compromised coats show rates as low as 30%. This disparity underscores the coat’s role in preserving viability until conditions favor growth.

To optimize germination efficiency, researchers often manipulate coat thickness or composition. For example, treating *Aspergillus niger* spores with 0.1% sodium hypochlorite weakens the coat, accelerating germination by 40% within 24 hours. Conversely, reinforcing the coat with chitin or silica nanoparticles delays germination but enhances long-term survival, a strategy employed in agricultural seed coatings. These interventions highlight the coat’s dual role: as both a barrier and a regulator of germination timing.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in biotechnology and food preservation. In the fermentation industry, *Lactobacillus* spores with engineered coats germinate 20% faster, improving production efficiency. Conversely, food safety protocols exploit coat weaknesses: heating *Clostridium botulinum* spores to 121°C for 3 minutes disrupts their coats, reducing germination by 99%. Understanding coat mechanics thus enables targeted control over spore behavior in diverse contexts.

A comparative analysis reveals that not all spores require equally strong coats. Endospore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium* rely heavily on durable coats for survival in harsh environments, whereas fungal spores often prioritize rapid germination over long-term resilience. This variation reflects evolutionary adaptations to specific ecological niches. For instance, *Penicillium* spores germinate within hours of landing on a nutrient source, their thin coats facilitating quick activation. Such differences emphasize the need to tailor strategies based on spore type and application.

In conclusion, the coat’s strength is a pivotal factor in germination efficiency, balancing protection and responsiveness. Whether weakening coats for rapid activation or reinforcing them for durability, precise manipulation of this structure unlocks practical benefits across industries. By studying coat mechanics, scientists can predict and control spore behavior, ensuring optimal outcomes in biotechnology, agriculture, and food safety.

Do Mold Spores Grow? Understanding Their Survival and Spread

You may want to see also

Trade-offs between protection and dispersal

Spores, the resilient survival structures of various organisms, face a critical evolutionary dilemma: the need for protection versus the imperative of dispersal. A strong coat, composed of materials like sporopollenin or chitin, shields spores from environmental stressors such as UV radiation, desiccation, and predation. However, this armor often comes at the cost of reduced mobility and dispersal efficiency. For instance, fungal spores with thick walls may withstand harsh conditions but struggle to travel far without external aids like wind or water. This trade-off highlights the delicate balance between survival and propagation in spore-producing organisms.

Consider the lifecycle of *Bacillus subtilis*, a bacterium that forms endospores with a multilayered coat. These spores can survive extreme temperatures and chemicals, remaining dormant for decades. Yet, their robust structure limits dispersal, relying heavily on external forces like soil movement or animal carriers. In contrast, plant spores, such as those of ferns, often have thinner walls to facilitate wind dispersal, sacrificing some durability. This comparison underscores how the strength of a spore coat is tailored to the organism’s ecological niche, prioritizing either protection or dispersal based on environmental demands.

For practical applications, understanding this trade-off is crucial in fields like agriculture and biotechnology. Farmers cultivating crops like wheat or rice, which rely on wind-dispersed pollen (a type of spore), benefit from thinner coats that enhance dispersal. However, in biopesticides or probiotics, where spores must survive harsh conditions, a stronger coat is advantageous. For example, *Bacillus thuringiensis* spores, used in pest control, are engineered with reinforced coats to withstand sunlight and rain, even if it means reduced dispersal range. Tailoring spore coat properties for specific purposes requires a nuanced approach, balancing protection and mobility.

A cautionary note: overemphasizing protection can render spores ineffective in reaching new habitats, limiting their ecological or agricultural utility. Conversely, prioritizing dispersal may leave spores vulnerable to environmental threats, reducing their viability. Researchers and practitioners must weigh these factors carefully. For instance, in spore-based vaccines, a moderate coat strength ensures survival during storage and transport while allowing for efficient delivery into the body. Striking this balance requires experimentation and a deep understanding of the spore’s intended environment and function.

In conclusion, the trade-off between protection and dispersal in spore coats is not a one-size-fits-all dilemma but a dynamic interplay shaped by evolutionary pressures and practical needs. By studying examples like bacterial endospores and plant pollen, we gain insights into how organisms navigate this challenge. Whether in nature or technology, the optimal spore coat is one that aligns with its purpose, ensuring survival without sacrificing the ability to colonize new territories. This principle guides innovations in agriculture, medicine, and beyond, where spores play pivotal roles.

Reminding Breloom's Spore: Tips and Strategies for Pokémon Trainers

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, a strong spore coat is essential for survival in harsh environments as it provides protection against desiccation, UV radiation, and other stressors.

Spores without a strong coat may germinate under favorable conditions but are more vulnerable to damage, reducing their long-term viability and survival rates.

Spores evolve stronger coats to adapt to their specific environments, ensuring better protection against local threats like extreme temperatures, chemicals, or predators.