Spores, which are reproductive structures produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, play a crucial role in the life cycles of these organisms. Understanding the ploidy of spore cells is essential for grasping their function and development. In many organisms, such as ferns and fungi, spores are typically haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. However, the question of whether a spore can have diploid cells—cells with two sets of chromosomes—arises in certain contexts, particularly in more complex life cycles or specific stages of development. Exploring this question sheds light on the diversity of reproductive strategies and genetic mechanisms across different species.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Ploidy of Spores in Most Fungi | Haploid (n) |

| Ploidy of Spores in Some Algae | Haploid (n) or Diploid (2n) depending on life cycle stage |

| Ploidy of Spores in Plants | Haploid (n) in bryophytes, pteridophytes, and seed plants (after meiosis) |

| Role of Spores | Reproductive units capable of developing into new organisms |

| Formation Process | Produced by meiosis in most organisms, ensuring genetic diversity |

| Exceptions | Some algae and fungi may produce diploid spores under specific conditions |

| Function in Life Cycle | Dispersal and survival in adverse environmental conditions |

| Genetic Composition | Typically haploid, carrying a single set of chromosomes |

| Comparison to Gametes | Similar to gametes in ploidy but differ in function and development |

| Significance in Evolution | Key to the alternation of generations in plants and some algae |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation Process: Spores develop through meiosis, reducing chromosome number to haploid

- Haploid vs. Diploid: Spores are typically haploid, not diploid, in most organisms

- Fungal Spores: Some fungi produce diploid spores, like zygospores, through karyogamy

- Plant Life Cycle: Alternation of generations includes diploid sporophyte and haploid gametophyte stages

- Bacterial Spores: Bacterial endospores are haploid, formed by single cells for survival

Spore Formation Process: Spores develop through meiosis, reducing chromosome number to haploid

Spores, the resilient survival structures of many organisms, are fundamentally haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. This haploid state is a direct result of the spore formation process, which begins with a diploid cell undergoing meiosis. Meiosis, a type of cell division, reduces the chromosome number by half, ensuring that spores carry only one set of genetic material. This reduction is critical for the life cycles of organisms like fungi, plants, and some protists, where alternation between haploid and diploid phases is essential for reproduction and genetic diversity.

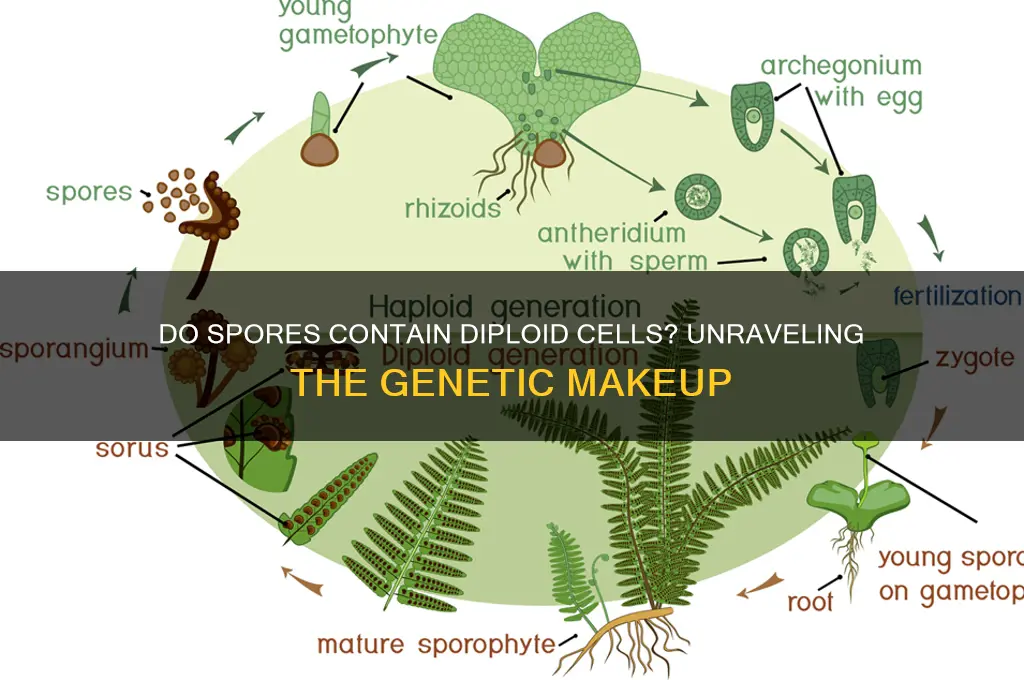

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a classic example of alternation of generations. The sporophyte (diploid) generation produces spores via meiosis in structures called sporangia. These spores, now haploid, germinate into gametophytes, which produce gametes (sperm and eggs). When fertilization occurs, a new diploid sporophyte is formed, completing the cycle. This process highlights the role of meiosis in spore formation, ensuring that each spore is genetically unique and capable of developing into a new organism under favorable conditions.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore formation is crucial in fields like agriculture and microbiology. For instance, in crop breeding, knowledge of haploid spores allows scientists to manipulate plant genetics more efficiently. Haploid plants, derived from spores, can be treated with colchicine to double their chromosome number, creating homozygous diploid lines in a single generation. This technique, known as haploid induction, significantly reduces breeding time and resources. Similarly, in microbiology, the haploid nature of fungal spores is exploited in genetic studies, where mutations can be easily tracked and analyzed.

However, the haploid state of spores also presents challenges. Haploid organisms are more susceptible to genetic defects because they lack a second set of chromosomes to mask recessive mutations. This vulnerability is mitigated by the spores' ability to remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. For example, fungal spores can survive extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation, ensuring their longevity and dispersal potential. This resilience underscores the evolutionary advantage of spore formation, despite the genetic risks associated with haploidy.

In conclusion, the spore formation process, driven by meiosis, is a cornerstone of life cycles in many organisms. By reducing the chromosome number to haploid, spores ensure genetic diversity and adaptability while maintaining the ability to survive harsh environments. Whether in the context of plant breeding, microbial genetics, or ecological resilience, the haploid nature of spores is both a biological necessity and a practical tool. Understanding this process not only deepens our appreciation of life's complexity but also informs strategies for innovation and conservation.

Are Magic Mushroom Spores Legal in Nevada? Exploring the Law

You may want to see also

Haploid vs. Diploid: Spores are typically haploid, not diploid, in most organisms

Spores, the resilient survival structures of many organisms, are predominantly haploid, carrying a single set of chromosomes. This contrasts with diploid cells, which contain two sets, typically one from each parent. In most fungi, plants, and some protozoa, spores are produced through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number by half, ensuring the resulting spores are haploid. This distinction is fundamental to understanding their role in life cycles and reproduction.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a classic example of alternation of generations. The fern plant we commonly see is a sporophyte, the diploid phase, which produces haploid spores via meiosis. These spores germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes, the haploid phase, which then produce gametes (sperm and eggs). Only after fertilization does a new diploid sporophyte emerge. This cycle underscores the rule: spores are haploid, serving as dispersal units rather than immediate contributors to genetic diversity.

However, exceptions exist. In certain fungi, like basidiomycetes (e.g., mushrooms), the spores are produced from a diploid structure called a basidium. Here, the diploid nucleus undergoes meiosis to form haploid basidiospores. Conversely, in some algae and protozoa, spores can be diploid, particularly in species with simplified life cycles. These outliers highlight the importance of context: while the norm is haploid spores, specific evolutionary adaptations have led to variations.

For practical applications, understanding spore ploidy is crucial. In agriculture, haploid spores of fungi like *Fusarium* or *Aspergillus* are targeted with fungicides to prevent crop diseases. In biotechnology, haploid spores of yeast are used in genetic studies due to their simplicity. Conversely, diploid spores in certain algae are exploited for biofuel production, as their higher genetic content can enhance biomass yield. Knowing whether a spore is haploid or diploid thus directly impacts strategies in pest control, research, and industry.

In summary, while spores are typically haploid in most organisms, exceptions remind us of nature’s diversity. This knowledge is not just academic—it informs practical decisions in fields ranging from ecology to biotechnology. Whether studying ferns or engineering algae, the ploidy of spores remains a key factor in their function and utility.

Do Land Plants Produce Haploid Spores? Exploring Plant Reproduction

You may want to see also

Fungal Spores: Some fungi produce diploid spores, like zygospores, through karyogamy

Fungi exhibit a fascinating diversity in their reproductive strategies, and one notable aspect is the production of diploid spores through a process called karyogamy. Unlike haploid spores, which are more common, diploid spores carry two sets of chromosomes, a characteristic that plays a crucial role in fungal life cycles. Among these, zygospores stand out as a prime example. Formed when two haploid hyphae fuse during sexual reproduction, zygospores encapsulate the union of genetic material, creating a resilient structure capable of withstanding harsh environmental conditions. This mechanism ensures genetic diversity and survival, particularly in unpredictable ecosystems.

To understand the significance of diploid spores, consider the lifecycle of fungi like *Zygomycota*. When two compatible haploid gametangia come into contact, their nuclei undergo karyogamy, merging to form a diploid zygote within the zygospore. This zygospore then enters a dormant phase, often referred to as a "resting spore," until conditions become favorable for germination. Upon germination, meiosis occurs, restoring the haploid state and producing new hyphae. This alternation between haploid and diploid phases, known as the haploid-diploid lifecycle, is a hallmark of many fungi and highlights the adaptive advantages of diploid spores.

From a practical standpoint, understanding diploid spores like zygospores is essential for fields such as agriculture and mycology. For instance, zygospores of *Rhizopus stolonifer*, a common bread mold, can survive for years in soil, posing challenges for crop management. Farmers and researchers can mitigate this by implementing crop rotation and soil sterilization techniques, targeting the dormant phase of these spores. Additionally, studying karyogamy in fungi provides insights into genetic recombination, which has applications in biotechnology, such as the production of bioactive compounds and enzymes.

Comparatively, diploid spores differ from haploid spores in their function and resilience. While haploid spores are more numerous and facilitate rapid colonization, diploid spores serve as a genetic reservoir, ensuring long-term survival and adaptability. This duality in spore types reflects the evolutionary sophistication of fungi, allowing them to thrive in diverse environments. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, observing the formation of zygospores under a microscope can be a rewarding experience, offering a glimpse into the intricate world of fungal reproduction.

In conclusion, the production of diploid spores, exemplified by zygospores, is a testament to the complexity and adaptability of fungi. Through karyogamy, fungi not only ensure genetic diversity but also enhance their survival capabilities. Whether you're a researcher, farmer, or simply curious about the natural world, exploring this aspect of fungal biology opens doors to practical applications and a deeper appreciation of microbial life. By focusing on these unique reproductive strategies, we gain valuable insights into the resilience and ingenuity of fungi.

Challenges in Sterilizing Spore-Forming Bacteria: Effective Methods Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Plant Life Cycle: Alternation of generations includes diploid sporophyte and haploid gametophyte stages

Spores are a fundamental part of the plant life cycle, but their ploidy—whether they are diploid or haploid—depends on the stage of the organism they represent. In the alternation of generations, a defining feature of plant life cycles, two distinct phases exist: the diploid sporophyte and the haploid gametophyte. Understanding this duality is crucial for grasping how plants reproduce and develop.

Consider the sporophyte generation, which is diploid (2n), meaning its cells contain two sets of chromosomes. This phase is dominant in vascular plants like ferns and flowering plants. The sporophyte produces spores through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number by half. These spores are not diploid; they are haploid (n), carrying a single set of chromosomes. This is a critical distinction: while the sporophyte itself is diploid, the spores it generates are haploid. These spores then develop into the gametophyte generation.

The gametophyte generation is haploid and typically smaller and less conspicuous than the sporophyte. In ferns, for example, the gametophyte is a tiny, heart-shaped structure that grows independently in moist environments. Its role is to produce gametes—sperm and egg cells—through mitosis, which retains the haploid state. When fertilization occurs, the resulting zygote is diploid, marking the beginning of a new sporophyte. This cyclical process ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in plant populations.

To illustrate, observe the life cycle of a moss. The dominant phase here is the gametophyte, which is haploid and produces gametes. After fertilization, the zygote develops into a sporophyte, which remains attached to the gametophyte. The sporophyte then produces haploid spores, restarting the cycle. This contrasts with flowering plants, where the sporophyte is dominant, but the principle of alternation remains the same.

In practical terms, understanding this alternation is essential for horticulture and agriculture. For instance, knowing that fern spores are haploid helps gardeners propagate them effectively by providing the right conditions for gametophyte growth. Similarly, in seed production, recognizing the diploid nature of the sporophyte ensures genetic stability in crops. By focusing on these stages, one can manipulate plant reproduction for desired outcomes, whether in conservation, breeding, or cultivation.

Black Mold Spores in Gypsum: Risks, Detection, and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Bacterial Spores: Bacterial endospores are haploid, formed by single cells for survival

Bacterial endospores, often simply called spores, are remarkable structures produced by certain bacteria as a survival mechanism. Unlike the spores of plants or fungi, which can contain diploid cells, bacterial endospores are haploid. This means they are formed from a single cell and carry only one set of chromosomes. The process, known as sporulation, is triggered by harsh environmental conditions such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or desiccation. These spores are not reproductive structures but rather dormant forms that allow bacteria to withstand conditions that would otherwise be lethal.

The formation of a bacterial endospore is a highly regulated, multi-step process. It begins with the replication of the bacterial chromosome, followed by the asymmetric division of the cell into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore, and layers of protective coatings are deposited around it. These layers include a spore coat, cortex, and sometimes an outer exosporium, which provide resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals. The entire process ensures that the genetic material remains intact, preserving the haploid state of the spore.

One of the most striking features of bacterial endospores is their resilience. For example, *Bacillus anthracis*, the bacterium responsible for anthrax, can survive in spore form for decades in soil. Similarly, *Clostridium botulinum* spores can withstand boiling water for hours, making them a significant concern in food preservation. This durability is why bacterial spores are often the target of sterilization processes in medical and industrial settings. Autoclaves, which use steam under pressure at 121°C for 15–20 minutes, are commonly employed to destroy spores in laboratory equipment and surgical instruments.

Understanding the haploid nature of bacterial endospores has practical implications for fields like microbiology, medicine, and food safety. For instance, knowing that spores are formed by single cells helps explain why they are so difficult to eradicate. Unlike diploid cells, which may have redundant genetic material, haploid spores rely on a single copy of their genome, making them highly efficient in their survival strategy. This efficiency underscores the importance of rigorous sterilization protocols in environments where bacterial contamination could have serious consequences.

In summary, bacterial endospores are haploid structures formed by single cells as a survival mechanism. Their ability to withstand extreme conditions stems from their protective layers and genetic simplicity. While this resilience poses challenges in sterilization, it also highlights the ingenuity of bacterial survival strategies. By focusing on the unique characteristics of bacterial spores, we can develop more effective methods to control and eliminate them in critical settings.

Exploring Pteridophytes: Understanding Their Spore-Based Reproduction and Classification

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It depends on the type of spore. In fungi, spores can be haploid (e.g., conidia) or diploid (e.g., zygospores). In plants, spores are typically haploid, produced by meiosis.

Fern spores are haploid. They are produced by meiosis in the sporophyte generation and develop into the gametophyte generation.

Some fungal spores, like zygospores, are diploid, formed by the fusion of two haploid gametes. Others, like conidia, are haploid and produced asexually.

No, plant spores are typically haploid. They are formed by meiosis in the sporophyte phase and grow into the gametophyte phase.

Yes, in certain fungi and some algae, spores can be diploid. For example, zygospores in fungi and carpospores in red algae are diploid.