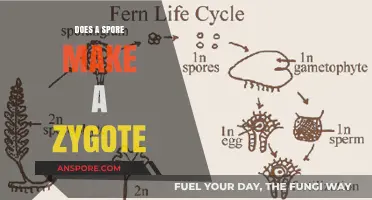

The question of whether a sporophyte begins as a spore is central to understanding the life cycle of plants, particularly in groups like ferns, mosses, and seed plants. In the alternation of generations, a fundamental characteristic of these organisms, the sporophyte is the diploid phase that produces spores through meiosis. However, the sporophyte itself does not originate directly from a single spore. Instead, a spore germinates into a haploid gametophyte, which then produces gametes. Fertilization of these gametes results in the formation of a zygote, which develops into the sporophyte. Thus, while spores are crucial to the life cycle, the sporophyte arises from the fusion of gametes, not directly from a spore.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Life Cycle Stage | The sporophyte is a diploid (2n) stage in the plant life cycle. |

| Origin | A sporophyte begins as a zygote, formed by the fusion of two haploid gametes (sperm and egg) during fertilization, not directly as a spore. |

| Spore Role | Spores are produced by the sporophyte through meiosis and give rise to the gametophyte (haploid, n stage). |

| Development | The sporophyte develops from the zygote, which undergoes mitotic divisions to form the multicellular sporophyte plant. |

| Alternation of Generations | Plants exhibit alternation of generations, where the sporophyte and gametophyte phases alternate. The sporophyte produces spores, which grow into gametophytes, and the gametophytes produce gametes that form the sporophyte. |

| Examples | In vascular plants (e.g., ferns, gymnosperms, angiosperms), the sporophyte is the dominant, visible stage (e.g., the fern plant or a tree). |

| Spore vs. Zygote | Spores are haploid and develop into gametophytes, while the sporophyte starts as a diploid zygote. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Germination Process: How does a single-celled spore initiate growth into a sporophyte

- Role of Meiosis: Does meiosis precede spore formation, and how does it relate to sporophytes

- Sporophyte Development Stages: What are the key stages from spore to mature sporophyte

- Environmental Triggers: How do factors like moisture and light influence spore-to-sporophyte transition

- Alternation of Generations: How does the sporophyte fit into the plant life cycle

Spore Germination Process: How does a single-celled spore initiate growth into a sporophyte?

A single-celled spore, dormant and resilient, holds the potential to develop into a sporophyte, the diploid phase of a plant's life cycle. This transformation begins with spore germination, a process triggered by environmental cues such as moisture, light, and temperature. Once activated, the spore's cell wall softens, allowing water uptake—a critical step known as imbibition. This influx of water rehydrates the spore, reactivating its metabolic processes and signaling the start of growth. For example, in ferns, spores require a humid environment to initiate germination, highlighting the importance of moisture in breaking dormancy.

The next phase involves the emergence of a protonema or prothallus, depending on the plant group. In mosses, the spore develops into a filamentous protonema, while in ferns, it forms a heart-shaped prothallus. These structures serve as the foundation for further sporophyte development. During this stage, the spore's stored nutrients are utilized to support cell division and differentiation. For instance, in *Physcomitrella patens* (a model moss species), the protonema grows through tip-cell division, a process regulated by auxin and cytokinin hormones. Understanding these early developmental stages is crucial for optimizing spore germination in laboratory settings, where controlled conditions can enhance success rates.

From a comparative perspective, spore germination varies significantly across plant groups. In bryophytes (mosses, liverworts, and hornworts), the sporophyte remains dependent on the gametophyte for nutrition, whereas in vascular plants like ferns and seed plants, the sporophyte becomes the dominant phase. This divergence underscores the evolutionary adaptations of spore germination. For practical applications, researchers often use gibberellic acid (GA3) at concentrations of 100–500 ppm to stimulate spore germination in ferns, demonstrating how chemical cues can mimic natural triggers.

Persuasively, mastering the spore germination process has profound implications for conservation and agriculture. For endangered plant species, such as certain orchids, spore germination techniques enable propagation in controlled environments, ensuring their survival. Similarly, in crop plants like wheat and rice, understanding spore-like structures (e.g., pollen grains) can improve breeding programs. A key takeaway is that spore germination is not a passive event but a highly regulated process influenced by genetics and environment. By manipulating these factors, scientists can harness the spore's potential to address challenges in biodiversity and food security.

Finally, a descriptive lens reveals the beauty of this process: a microscopic spore, once inert, unfolds into a complex sporophyte through a symphony of cellular events. The transition from dormancy to growth is a testament to nature's ingenuity. Observing this under a microscope, one can witness the first cell divisions, the formation of rhizoids anchoring the young plant, and the gradual emergence of photosynthetic tissues. This intricate dance of life, initiated by a single spore, underscores the elegance of plant biology and invites further exploration into its mechanisms.

Buying Magic Mushroom Spore Kits in the US: Legal or Not?

You may want to see also

Role of Meiosis: Does meiosis precede spore formation, and how does it relate to sporophytes?

Meiosis, a specialized form of cell division, is the cornerstone of sexual reproduction in plants, including the life cycle of sporophytes. It is a process that reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid cells from diploid precursors. This reduction is crucial for the formation of spores, which are the initial cells of the gametophyte generation in the plant life cycle. Therefore, meiosis does indeed precede spore formation, setting the stage for the development of sporophytes.

To understand this relationship, consider the sequence of events in a typical plant life cycle. A sporophyte, the diploid phase, undergoes meiosis in its reproductive organs, such as sporangia. This meiotic division results in the production of haploid spores. Each spore then germinates and grows into a gametophyte, which is the haploid phase. The gametophyte produces gametes (sperm and egg cells) through mitosis. When fertilization occurs, the resulting zygote develops into a new sporophyte, completing the cycle. This process highlights the essential role of meiosis in bridging the diploid and haploid phases of the plant life cycle.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the timing and function of meiosis in spore formation is vital for plant breeding and conservation efforts. For instance, in agriculture, manipulating meiotic processes can lead to the development of hybrid plants with desirable traits. In conservation biology, knowledge of meiosis helps in preserving genetic diversity by ensuring that spore formation occurs naturally in endangered plant species. Techniques such as controlled pollination and spore culture rely on this understanding to propagate plants effectively.

Comparatively, meiosis in sporophytes differs from mitosis in its outcome and purpose. While mitosis maintains the chromosome number and is involved in growth and repair, meiosis reduces the chromosome number and is essential for genetic diversity. This diversity is critical for the survival of plant species, as it allows populations to adapt to changing environments. For example, in ferns, meiosis ensures that each spore has a unique genetic makeup, increasing the chances of successful colonization in varied habitats.

In conclusion, meiosis is not only a precursor to spore formation but also a fundamental process that links sporophytes to the next generation. Its role in reducing chromosome number and introducing genetic variation is indispensable for the continuity and adaptability of plant life. Whether in the context of natural ecosystems or human-directed plant cultivation, the interplay between meiosis, spore formation, and sporophyte development underscores the complexity and elegance of plant reproduction.

Spelunker Potion: Revealing Jungle Spores in Minecraft Explained

You may want to see also

Sporophyte Development Stages: What are the key stages from spore to mature sporophyte?

The sporophyte generation in plants begins with a single spore, a microscopic, unicellular structure produced by the parent plant. This spore is the starting point of a complex journey, marking the transition from the haploid gametophyte phase to the diploid sporophyte phase in the plant life cycle. Understanding the development stages from spore to mature sporophyte is crucial for botanists, horticulturists, and anyone interested in plant reproduction and growth.

Germination and Early Development

The first stage of sporophyte development is spore germination, triggered by environmental cues like moisture, light, or temperature. During germination, the spore absorbs water, swells, and divides mitotically to form a multicellular structure called the sporeling. In ferns, for example, the spore develops into a heart-shaped prothallus, the gametophyte stage. However, in seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms), the spore directly develops into the embryonic sporophyte within a protective seed coat. This early stage is critical, as it sets the foundation for the sporophyte’s future growth and requires precise conditions to succeed.

Embryonic Growth and Differentiation

Once the sporeling is established, it enters the embryonic growth phase. In seed plants, this occurs within the seed, where the embryo develops rudimentary roots (radicle), shoots (plumule), and cotyledons (seed leaves). Nutrients stored in the seed endosperm or cotyledons fuel this growth. In non-seed plants like ferns, the embryonic sporophyte emerges from the gametophyte and becomes dependent on it for nutrients until it develops its own photosynthetic capability. This stage is marked by cell differentiation, where tissues and organs begin to form, laying the groundwork for the mature sporophyte.

Seedling Establishment and Photosynthetic Independence

For seed plants, the next critical stage is seedling establishment, which begins when the seed coat ruptures and the radicle emerges (germination). The seedling relies on stored energy initially but quickly transitions to photosynthesis as the first true leaves unfurl. In ferns and other spore-producing plants, the young sporophyte becomes photosynthetically active while still attached to the gametophyte, gradually severing its dependence. This stage is vulnerable to environmental stressors like drought or herbivory, making adequate water, light, and nutrient availability essential.

Maturation and Reproductive Competence

The final stage of sporophyte development is maturation, characterized by full growth and reproductive competence. In ferns, the mature sporophyte produces sporangia on the undersides of its fronds, which release spores to start the cycle anew. In seed plants, maturation involves the development of flowers (angiosperms) or cones (gymnosperms), culminating in the production of seeds. This stage requires significant energy investment and is influenced by factors like day length, temperature, and nutrient availability. For example, short days often trigger flowering in many angiosperms, while gymnosperms may take years to reach reproductive maturity.

Practical Tips for Supporting Sporophyte Development

To ensure successful sporophyte development, maintain consistent moisture during germination, especially for spore-producing plants like ferns. For seedlings, provide bright, indirect light and gradually acclimate them to direct sunlight. Use well-draining soil and avoid overwatering to prevent root rot. For mature sporophytes, monitor nutrient levels and apply balanced fertilizers as needed. Understanding these stages allows for targeted interventions, whether in a garden, greenhouse, or laboratory setting, to foster healthy plant growth and reproduction.

Do Jack Frost Mushrooms Release Spores? A Fungal Mystery Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers: How do factors like moisture and light influence spore-to-sporophyte transition?

The transition from spore to sporophyte in plants is a delicate process, heavily influenced by environmental factors. Among these, moisture and light play pivotal roles, acting as critical triggers that determine whether a spore germinates and develops into a sporophyte. Moisture, for instance, is essential for activating the metabolic processes within the spore, enabling it to break dormancy and initiate growth. Without adequate water, spores remain dormant, unable to absorb nutrients or undergo cell division. Light, on the other hand, often acts as a signal for directional growth, guiding the emerging sporophyte toward optimal conditions for photosynthesis and survival.

Consider the lifecycle of ferns, a classic example of spore-to-sporophyte development. Spores released from the underside of fern fronds require a moist substrate to germinate. In nature, this often means landing on damp soil or decaying wood. Once hydrated, the spore absorbs water, swelling and rupturing its protective wall to form a protonema, a filamentous structure that eventually develops into the sporophyte. Light then becomes crucial during this stage, as it directs the protonema to grow toward brighter areas, ensuring the young sporophyte can efficiently photosynthesize. For gardeners cultivating ferns, maintaining a humidity level of 60–70% and providing indirect, filtered light mimics these natural conditions, fostering successful spore germination.

In contrast, some plant species, like certain mosses, exhibit a more nuanced response to light during the spore-to-sporophyte transition. For example, *Physcomitrella patens*, a model organism in bryophyte research, shows phototropism during protonema development, with blue light specifically influencing growth direction. This sensitivity to light wavelength highlights the precision with which environmental cues can guide developmental processes. In laboratory settings, researchers use controlled light spectra (e.g., 450 nm blue light) to study these responses, underscoring the importance of light quality, not just quantity, in spore development.

Moisture and light do not act in isolation; their interplay often determines the success of the spore-to-sporophyte transition. For instance, in arid environments, spores of resurrection plants like *Selaginella lepidophylla* remain dormant until a rare combination of moisture and light signals favorable conditions. This dual requirement ensures that germination occurs only when water is available and light indicates a suitable habitat. Such adaptations illustrate how environmental triggers have shaped evolutionary strategies, balancing the need for growth with the risk of desiccation.

Practical applications of these insights extend beyond botany. In agriculture and horticulture, understanding these triggers can optimize the propagation of spore-bearing plants. For example, orchid growers use misting systems to maintain high humidity (80–90%) around spores, while carefully calibrated grow lights provide the necessary spectrum for healthy sporophyte development. Similarly, in conservation efforts, reintroducing spore-bearing plants to degraded habitats requires precise control of moisture and light to ensure successful establishment. By harnessing these environmental triggers, we can foster the growth of sporophytes, bridging the gap between spore and mature plant with precision and care.

Are Spores Harmful to Humans? Understanding Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Alternation of Generations: How does the sporophyte fit into the plant life cycle?

The sporophyte generation in plants is a critical phase in the alternation of generations, a life cycle that toggles between two distinct forms: the diploid sporophyte and the haploid gametophyte. To understand how the sporophyte fits into this cycle, consider its origin. A sporophyte does not begin as a spore; rather, it arises from the fusion of gametes produced by the gametophyte generation. This process, known as fertilization, results in a zygote that develops into the sporophyte. For example, in ferns, the sporophyte is the large, visible plant we typically recognize, while the gametophyte is a small, heart-shaped structure that grows in moist environments.

Analyzing the sporophyte’s role reveals its primary function: to produce spores through meiosis. These spores are not the starting point of the sporophyte but rather the endpoint of its reproductive phase. Spores germinate into gametophytes, which then produce gametes to restart the cycle. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability. In mosses, the sporophyte is dependent on the gametophyte for nutrients, while in more complex plants like angiosperms, the sporophyte is the dominant generation, with the gametophyte reduced to structures like pollen grains and embryo sacs.

To visualize this process, imagine a fern’s life cycle. The sporophyte produces spores on the undersides of its fronds. These spores develop into gametophytes, which release sperm and eggs. Fertilization occurs when sperm swim to the egg, forming a zygote that grows into a new sporophyte. This cycle highlights the sporophyte’s role as both a product of fertilization and a producer of spores, bridging the two generations.

Practical observations of this cycle can be made in the garden or classroom. For instance, planting fern spores in a damp, shaded area allows you to observe gametophyte development. Over time, young sporophytes will emerge, demonstrating the transition from spore to gametophyte to sporophyte. This hands-on approach reinforces the concept that the sporophyte is not the beginning but a pivotal stage in the cycle.

In conclusion, the sporophyte’s place in the plant life cycle is defined by its role as a spore producer and its origin from the fusion of gametes. By understanding this, we gain insight into the intricate balance of alternation of generations, a mechanism that has ensured the survival and diversity of plant life for millions of years. Whether in ferns, mosses, or flowering plants, the sporophyte’s function remains central to this dynamic process.

Cypress Trees and Spores: Unveiling the Truth About Their Reproduction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a sporophyte does not begin as a spore. The sporophyte is the diploid phase of a plant's life cycle that produces spores through meiosis.

The gametophyte begins as a spore. A spore germinates and grows into a haploid gametophyte, which then produces gametes.

A sporophyte develops from the fusion of two gametes (sperm and egg) produced by the gametophyte. This fertilization results in a diploid zygote, which grows into the sporophyte.