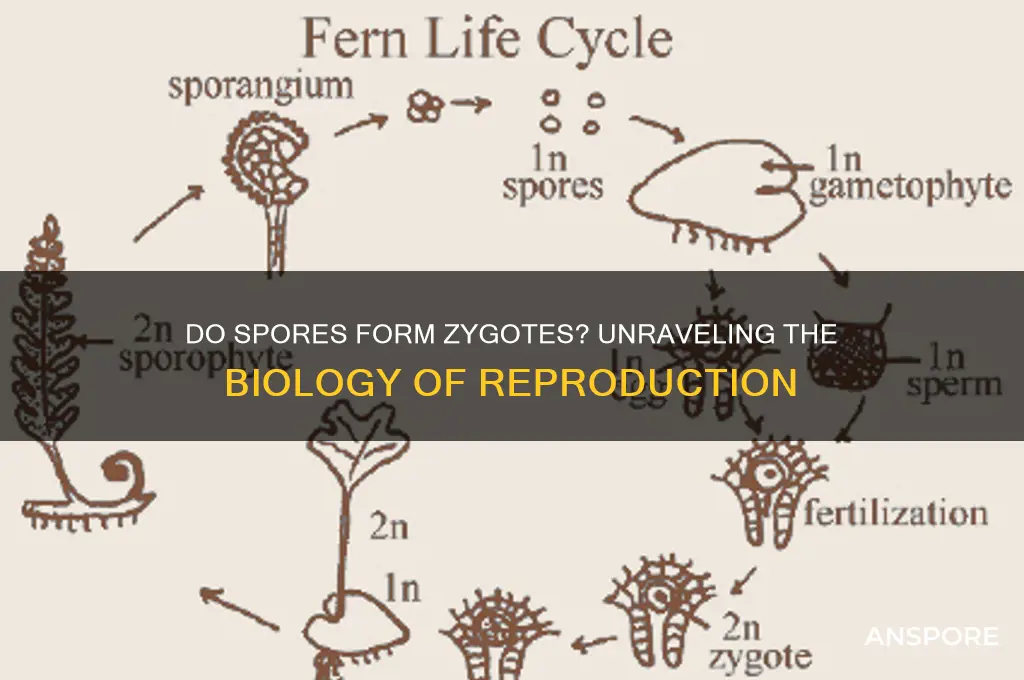

The question of whether a spore can make a zygote delves into the fundamental differences between asexual and sexual reproduction in organisms. Spores are typically associated with asexual reproduction, particularly in plants, fungi, and some protists, where they serve as resilient, single-celled structures capable of developing into a new individual without fertilization. In contrast, a zygote is the product of sexual reproduction, formed when two gametes (sex cells) fuse, combining genetic material from two parents. While both spores and zygotes are crucial for the life cycles of various organisms, they arise from distinct reproductive processes, and spores generally do not directly form zygotes. However, in certain organisms with complex life cycles, such as ferns, spores develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes that can form a zygote, highlighting the interplay between these reproductive mechanisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Involved | Spores do not directly form zygotes. Spores are haploid cells produced by plants, fungi, and some protists through sporulation (asexual or sexual). Zygotes are formed through fertilization, the fusion of two haploid gametes (e.g., sperm and egg). |

| Ploidy | Spores are haploid (n chromosomes). Zygotes are diploid (2n chromosomes) after fertilization. |

| Function | Spores are primarily for dispersal and survival in harsh conditions. Zygotes are the initial stage of a new multicellular organism after sexual reproduction. |

| Organisms Involved | Spores are produced by plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), fungi, and some protists. Zygotes are formed in multicellular organisms that undergo sexual reproduction (e.g., animals, plants, some fungi). |

| Life Cycle Stage | Spores are part of the alternation of generations in plants and fungi. Zygotes mark the beginning of the diploid phase in organisms with sexual reproduction. |

| Direct Relationship | No direct relationship; spores and zygotes are distinct stages in different reproductive processes. |

| Example | Fern spores grow into gametophytes, which produce gametes. Fertilization of these gametes forms a zygote, which develops into a new fern plant. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore vs. Zygote Formation: Spores result from meiosis; zygotes from fertilization, distinct reproductive processes in organisms

- Role in Life Cycles: Spores in alternation of generations; zygotes in sexual reproduction, key developmental stages

- Genetic Differences: Spores are haploid, single-celled; zygotes diploid, fusion of gametes, genetic variation

- Environmental Survival: Spores are dormant, resilient; zygotes develop immediately, vulnerable to conditions

- Organisms Involved: Spores in fungi, plants, ferns; zygotes in animals, some algae, reproductive diversity

Spore vs. Zygote Formation: Spores result from meiosis; zygotes from fertilization, distinct reproductive processes in organisms

Spores and zygotes are fundamental to the reproductive strategies of different organisms, yet they arise from distinct biological processes. Spores are the product of meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid cells. This process occurs in plants, fungi, and some protists, enabling them to disperse and survive harsh conditions. For example, fern plants release spores that can lie dormant for years before germinating into new individuals. In contrast, zygotes form through fertilization, where two haploid gametes—typically an egg and a sperm—fuse to create a diploid cell. This process is central to sexual reproduction in animals and many plants, ensuring genetic diversity. Understanding these differences is crucial for grasping how various organisms perpetuate their species.

Consider the life cycle of a mushroom to illustrate spore formation. After a fungus matures, it undergoes meiosis within its gills or pores, producing spores that are released into the environment. These spores are lightweight and can travel vast distances via wind or water, eventually landing in suitable habitats where they germinate and grow into new fungal individuals. This asexual method of reproduction allows fungi to colonize diverse environments efficiently. Conversely, fertilization in animals, such as humans, involves the union of a sperm and an egg within the female reproductive tract. The resulting zygote undergoes mitosis, developing into an embryo and eventually a fetus. While both spores and zygotes are reproductive units, their formation and function differ dramatically, reflecting the evolutionary adaptations of their respective organisms.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these processes has significant applications in agriculture, medicine, and conservation. For instance, farmers use spore-based fungicides to control plant diseases, leveraging the natural dispersal mechanisms of fungi. In medicine, research on zygote development informs assisted reproductive technologies like in vitro fertilization (IVF), where embryos are cultured outside the body before implantation. Conservationists also study spore and zygote formation to protect endangered species, such as coral reefs, which rely on both asexual and sexual reproduction to recover from environmental stressors. By recognizing the unique roles of spores and zygotes, scientists can develop targeted strategies to address challenges in these fields.

A comparative analysis highlights the efficiency and resilience of spore-based reproduction versus the genetic diversity fostered by zygote formation. Spores excel in survival, capable of withstanding extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation. This makes them ideal for organisms in unpredictable environments, such as deserts or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Zygotes, on the other hand, introduce genetic variation through the recombination of parental DNA, enhancing a species’ ability to adapt to changing conditions over generations. For example, the sexual reproduction of flowering plants ensures that each seedling has a unique genetic makeup, increasing the likelihood that some will thrive in evolving ecosystems. Both strategies have evolved to maximize reproductive success, but they serve different ecological purposes.

In conclusion, while spores and zygotes are both reproductive units, their origins and functions are distinctly tied to the survival and diversification of organisms. Spores, born from meiosis, are hardy and dispersible, enabling asexual reproduction in challenging environments. Zygotes, formed through fertilization, combine genetic material to create diverse offspring, a cornerstone of sexual reproduction. By examining these processes, we gain insights into the intricate ways life perpetuates itself across the biological kingdom. Whether in a laboratory, a farm, or the wild, understanding spore and zygote formation empowers us to innovate, conserve, and appreciate the complexity of life’s reproductive strategies.

Wild Animals vs. Villages: Can They Destroy Spore Settlements?

You may want to see also

Role in Life Cycles: Spores in alternation of generations; zygotes in sexual reproduction, key developmental stages

Spores and zygotes are fundamental to the life cycles of various organisms, yet they serve distinct roles in reproduction and development. Spores are pivotal in the alternation of generations, a life cycle where organisms alternate between diploid and haploid phases. In plants like ferns and algae, spores develop into haploid gametophytes, which produce gametes. These gametes then fuse to form a zygote, a diploid cell that grows into the sporophyte generation, completing the cycle. This process ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in changing environments.

Zygotes, on the other hand, are the starting point of sexual reproduction in multicellular organisms, including animals and many plants. Formed by the fusion of two haploid gametes—sperm and egg—the zygote is the first diploid cell of a new organism. It undergoes rapid cell division (cleavage) and differentiation, laying the foundation for complex developmental stages. For instance, in humans, the zygote divides into a blastocyst within days, which implants into the uterus and eventually develops into a fetus. This stage is critical, as errors during zygote formation or early division can lead to developmental abnormalities.

While spores and zygotes both contribute to life cycles, their functions are non-interchangeable. Spores are not zygotes; they are haploid cells that give rise to gametophytes, whereas zygotes are diploid cells that develop into new individuals. Confusing the two would overlook their unique roles in alternation of generations versus sexual reproduction. For example, in mosses, spores grow into protonema (a gametophyte stage), which then produces gametes. The zygote formed from these gametes develops into the sporophyte, which produces more spores. This clear distinction highlights their complementary yet separate roles.

Understanding these roles is crucial for fields like botany, zoology, and biotechnology. For instance, in agriculture, manipulating spore development can enhance crop resilience, while in medicine, studying zygote formation aids in fertility treatments. Practical tips include maintaining optimal humidity for spore germination in plant cultivation and ensuring genetic compatibility in zygote formation for assisted reproduction. By recognizing the unique contributions of spores and zygotes, we can better harness their potential in both natural and applied contexts.

Fungi and Meiosis: Understanding Spores Production in Fungal Reproduction

You may want to see also

Genetic Differences: Spores are haploid, single-celled; zygotes diploid, fusion of gametes, genetic variation

Spores and zygotes, though both pivotal in the life cycles of organisms, diverge fundamentally in their genetic composition and formation. Spores are haploid, meaning they carry a single set of chromosomes, typically produced through meiosis in organisms like fungi, plants, and some protists. This haploid nature allows spores to develop into new individuals without fertilization, a process known as sporulation. In contrast, zygotes are diploid, formed by the fusion of two haploid gametes—sperm and egg—during sexual reproduction. This fusion doubles the chromosome count, creating a genetically unique offspring. Understanding this distinction is crucial for grasping how different organisms propagate and diversify.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a plant that relies on spores for reproduction. When a fern releases spores, each spore is a single, haploid cell capable of growing into a gametophyte, which then produces gametes. These gametes fuse to form a diploid zygote, which develops into the mature fern. Here, the spore is not a zygote but a precursor to the gametophyte stage. In contrast, humans and many animals bypass spores entirely, relying on zygotes formed directly from gamete fusion. This comparison highlights the distinct roles of spores and zygotes in genetic continuity and variation.

From a practical standpoint, the genetic differences between spores and zygotes have significant implications in fields like agriculture and medicine. For instance, plant breeders exploit spore-based reproduction in fungi to develop disease-resistant strains, as spores can rapidly multiply and adapt. In contrast, zygote-based reproduction in crops like corn allows for hybridization, combining desirable traits from two parents. Understanding these mechanisms enables scientists to manipulate genetic diversity effectively. For hobbyists growing mushrooms at home, knowing that spores are haploid explains why a single spore can colonize an entire substrate without a mate, while zygotes require the union of two distinct gametes.

The genetic variation introduced by zygotes through sexual reproduction offers a survival advantage by creating offspring with unique combinations of traits, enhancing adaptability to changing environments. Spores, while less genetically diverse, provide resilience through sheer numbers and the ability to remain dormant until conditions are favorable. For example, bacterial endospores can survive extreme conditions for years, while zygotes in animals are immediately vulnerable but carry the potential for rapid evolution. This trade-off between stability and innovation underscores the evolutionary strategies behind these reproductive methods.

In summary, spores and zygotes represent distinct genetic and reproductive strategies. Spores, haploid and single-celled, enable asexual reproduction and rapid dispersal, while zygotes, diploid and formed from gamete fusion, drive genetic variation through sexual reproduction. Recognizing these differences not only clarifies their roles in biology but also informs practical applications in biotechnology, conservation, and even home gardening. Whether studying ferns or breeding crops, this knowledge is indispensable for understanding life’s diversity.

Can Most Bacteria Form Spores? Unveiling Microbial Survival Strategies

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Survival: Spores are dormant, resilient; zygotes develop immediately, vulnerable to conditions

Spores and zygotes represent two distinct reproductive strategies in the biological world, each tailored to specific environmental challenges. Spores, produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are dormant, highly resilient structures designed to withstand harsh conditions. They can remain viable for years, even decades, in extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation. This dormancy allows them to persist until conditions improve, ensuring survival in unpredictable environments. In contrast, zygotes, the product of sexual reproduction in animals and some plants, are immediately active and vulnerable. They require stable, nutrient-rich conditions to develop, making them ill-suited for harsh or fluctuating environments. This fundamental difference in survival strategy highlights the trade-offs between resilience and rapid development.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern versus that of a mammal. Ferns release spores that can lie dormant in soil for years, waiting for the right combination of moisture and warmth to germinate. This strategy ensures that ferns can colonize even the most inhospitable environments, from rocky crevices to forest floors. Mammals, on the other hand, produce zygotes that must develop within a protective womb or egg, requiring consistent temperature, nutrients, and protection from predators. A human zygote, for instance, is entirely dependent on the maternal environment for survival, with even slight deviations in temperature or nutrient availability potentially leading to developmental issues. This comparison underscores the adaptability of spores and the fragility of zygotes in the face of environmental challenges.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences has significant implications for fields like agriculture, conservation, and medicine. Farmers can exploit the resilience of spores by using spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus thuringiensis*, as natural pesticides that survive harsh conditions. In conservation, efforts to protect endangered species often focus on creating stable environments for zygote development, such as controlled breeding programs for coral reefs or captive breeding of endangered mammals. In medicine, the dormancy of spores is both a challenge and an opportunity: while it allows pathogens like *Clostridium difficile* to persist in hospital environments, it also inspires research into inducing dormancy in cancer cells to halt tumor growth.

To illustrate the environmental survival advantage of spores, consider the Antarctic lichen *Buellia frigida*. Its spores can survive temperatures as low as -20°C and high UV radiation, remaining dormant until a rare thaw allows them to grow. In contrast, the zygotes of polar fish like the Antarctic icefish require stable, ice-free waters to develop, making them highly susceptible to climate change. This example highlights how spores’ resilience enables survival in extreme environments, while zygotes’ immediate development limits their adaptability. For those studying or working in extreme conditions, recognizing these differences can guide strategies for preservation, cultivation, or eradication of species.

In conclusion, the contrast between spores and zygotes in environmental survival boils down to a choice between resilience and vulnerability. Spores’ dormancy and toughness make them masters of survival in unpredictable or harsh conditions, while zygotes’ immediate development demands stability and protection. This distinction is not just a biological curiosity but a practical guide for addressing real-world challenges, from preserving biodiversity to combating disease. By leveraging the strengths of each strategy, we can develop more effective solutions for a rapidly changing world.

Are Spores Seeds? Unraveling the Differences and Similarities

You may want to see also

Organisms Involved: Spores in fungi, plants, ferns; zygotes in animals, some algae, reproductive diversity

Spores and zygotes are fundamental to the reproductive strategies of diverse organisms, yet they serve distinct roles across different kingdoms. In fungi, plants, and ferns, spores are the primary agents of reproduction, often dispersed through wind, water, or animals to colonize new environments. These microscopic structures are haploid, meaning they carry a single set of chromosomes, and can develop into new individuals without fertilization. For instance, ferns release spores that grow into gametophytes, which then produce eggs and sperm. In contrast, zygotes—formed by the fusion of two gametes—are the starting point for new life in animals and some algae. This diploid cell carries a full set of chromosomes and develops into a multicellular organism. Understanding these differences highlights the reproductive diversity across life forms.

Consider the lifecycle of a mushroom, a common fungus, to illustrate spore-based reproduction. After a mushroom matures, it releases millions of spores from its gills. These spores can travel vast distances and, upon landing in a suitable environment, germinate into thread-like structures called hyphae. These hyphae grow and eventually form a new mushroom, completing the cycle. This asexual method allows fungi to thrive in diverse habitats, from forest floors to decaying matter. In plants like mosses, spores play a similar role, enabling them to colonize harsh environments where seeds might fail. This adaptability underscores the efficiency of spore-based reproduction in certain ecosystems.

Zygotes, on the other hand, are the cornerstone of sexual reproduction in animals and some algae. In humans, for example, a zygote forms when a sperm fertilizes an egg, marking the beginning of embryonic development. This process ensures genetic diversity by combining traits from both parents. Similarly, in algae like the sea lettuce (*Ulva*), zygotes develop into sporophytes, which produce spores to continue the lifecycle. While zygotes require specific conditions for fertilization, they offer evolutionary advantages by promoting variation and resilience in offspring. This contrast between spores and zygotes reveals the trade-offs between rapid colonization and genetic diversity in reproductive strategies.

Practical applications of understanding these reproductive methods are evident in agriculture and conservation. For instance, farmers use spore-based techniques to cultivate mushrooms commercially, often controlling humidity and substrate composition to optimize growth. In plant conservation, spores from endangered ferns can be collected and propagated in controlled environments to bolster wild populations. Conversely, in animal breeding, knowledge of zygote formation guides assisted reproductive technologies like in vitro fertilization (IVF), which has revolutionized human and livestock reproduction. These examples demonstrate how insights into spores and zygotes can be harnessed to address real-world challenges.

Ultimately, the distinction between spores and zygotes reflects the remarkable diversity of life’s reproductive strategies. Spores excel in dispersal and asexual reproduction, making them ideal for fungi, plants, and ferns in varied environments. Zygotes, by contrast, drive sexual reproduction in animals and some algae, fostering genetic diversity essential for adaptation. By studying these mechanisms, scientists and practitioners can unlock innovations in fields ranging from ecology to medicine, underscoring the interconnectedness of life’s fundamental processes.

Can Stun Spore Effectively Counter Excadrill in Competitive Battles?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a spore does not directly make a zygote. Spores are reproductive cells produced by plants, fungi, and some microorganisms that can grow into new individuals without fertilization. Zygotes, on the other hand, are formed by the fusion of gametes (sex cells) in sexual reproduction.

No, spores and zygotes are not the same. Spores are asexual reproductive units that develop into new organisms without fertilization, while zygotes are the result of the fusion of male and female gametes in sexual reproduction.

In some organisms, like certain fungi and plants, spores can grow into structures that produce gametes, which then fuse to form a zygote. However, the spore itself does not directly become a zygote; it is an intermediate step in the life cycle.

Not necessarily. Some organisms, like bacteria and many fungi, reproduce solely through spores and do not produce zygotes. Zygotes are specific to organisms that undergo sexual reproduction, while spores are often associated with asexual or alternation of generation life cycles.