*Bacillus subtilis*, a Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium, is widely recognized for its ability to form highly resistant endospores under adverse environmental conditions. These spores serve as a survival mechanism, allowing the bacterium to endure extreme temperatures, desiccation, and other stressors. The formation of spores is a key characteristic of *B. subtilis* and has been extensively studied due to its significance in both scientific research and industrial applications. Understanding whether *B. subtilis* produces spores is fundamental to appreciating its ecological role, biotechnological potential, and applications in fields such as food preservation, probiotics, and biofertilizers.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: How and under what conditions does B. subtilis form spores

- Spore Structure: Key components and layers of B. subtilis spores

- Spore Function: Role of spores in B. subtilis survival and persistence

- Spore Germination: Triggers and mechanisms for B. subtilis spore activation

- Spore Applications: Uses of B. subtilis spores in industry and research

Sporulation Process: How and under what conditions does B. subtilis form spores?

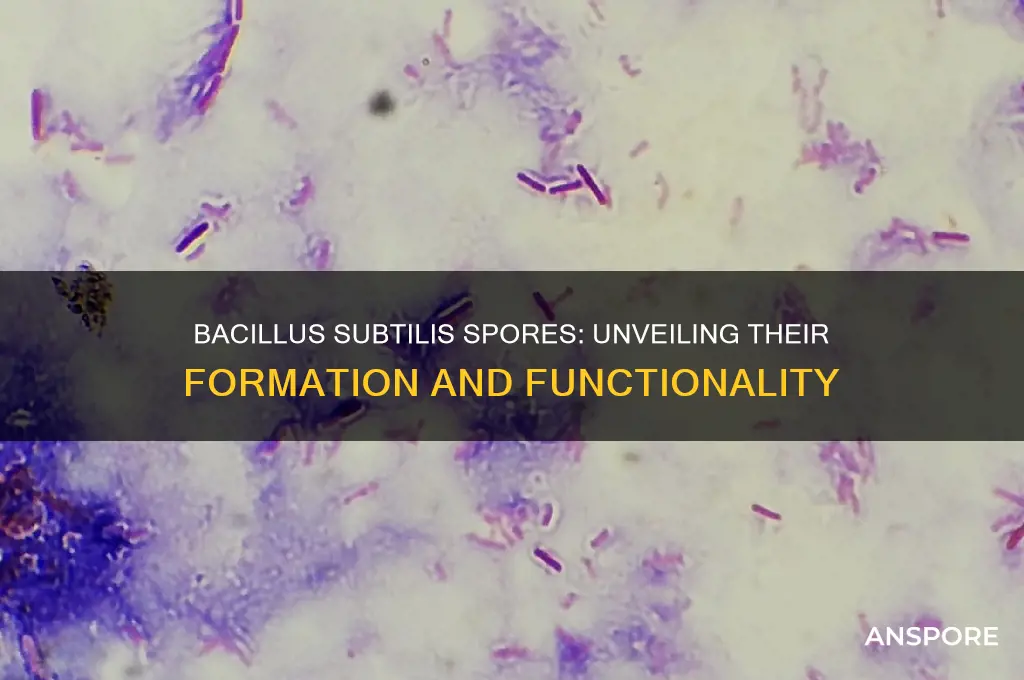

Bacillus subtilis, a rod-shaped, Gram-positive bacterium, is renowned for its ability to form highly resistant endospores, often simply called spores. These structures are not just a survival mechanism but a marvel of biological engineering, allowing the bacterium to endure extreme conditions that would otherwise be lethal. The sporulation process in B. subtilis is a complex, multi-stage transformation triggered by nutrient deprivation, particularly the lack of carbon and nitrogen sources. This process is not merely a passive response but a highly regulated, energy-intensive program that ensures the bacterium’s long-term survival.

The sporulation process begins with an asymmetric cell division, where the bacterium divides into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. This division is orchestrated by a series of signaling pathways, primarily involving the phosphorylation of the master regulator Spo0A. Once activated, Spo0A initiates the expression of genes required for spore formation. The forespore is then engulfed by the mother cell, creating a double-membrane structure. During this engulfment, the mother cell synthesizes a thick, protective coat around the forespore, composed of multiple layers of proteins, peptides, and calcium-dipicolinic acid. This coat is critical for the spore’s resistance to heat, desiccation, and chemicals.

The conditions under which B. subtilis initiates sporulation are precise and environmentally driven. Nutrient limitation, particularly the depletion of carbon and nitrogen sources, is the primary trigger. However, other factors such as pH, temperature, and population density (quorum sensing) also play a role. For instance, sporulation is most efficient at temperatures between 25°C and 37°C, with optimal conditions around 30°C. Additionally, the presence of certain amino acids, like L-valine, can inhibit sporulation, while others, like L-alanine, can promote it. Practical applications of this knowledge are seen in laboratory settings, where researchers manipulate these conditions to study sporulation or produce spores for industrial use.

One of the most fascinating aspects of B. subtilis sporulation is its reversibility under certain conditions. If nutrients become available during the early stages of sporulation, the bacterium can abort the process and resume vegetative growth. This flexibility highlights the bacterium’s adaptability and the sophistication of its regulatory mechanisms. However, once the spore coat is fully formed, the process becomes irreversible, and the spore enters a dormant state. This dormancy can last for years, even decades, until conditions favorable for germination arise, such as the presence of nutrients and appropriate temperature.

Understanding the sporulation process of B. subtilis has significant practical implications. Spores are used in probiotics, biocontrol agents, and as delivery vehicles in biotechnology. For example, B. subtilis spores are commonly added to animal feed to improve gut health and reduce pathogen colonization. In biotechnology, spores are engineered to produce enzymes or other biomolecules under harsh conditions. By manipulating the sporulation process, scientists can optimize spore production and functionality, making B. subtilis an invaluable tool in both research and industry.

Exploring Interplanetary Warfare in Spore: Strategies and Possibilities

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: Key components and layers of B. subtilis spores

Bacillus subtilis, a rod-shaped, Gram-positive bacterium, is renowned for its ability to form highly resistant endospores under adverse environmental conditions. These spores are not merely survival capsules but intricate structures with distinct layers, each contributing to their remarkable durability. Understanding the spore structure of B. subtilis is crucial for applications in biotechnology, food preservation, and even space exploration, where resilience against extreme conditions is paramount.

At the core of the spore lies the core wall, a modified peptidoglycan layer that provides structural integrity and protects the genetic material. Enclosed within this wall is the spore cytoplasm, which contains the DNA, ribosomes, and essential enzymes in a dehydrated state. This dehydration, coupled with the presence of dipicolinic acid (DPA), stabilizes the cellular components and confers resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals. DPA, a calcium-chelating agent, constitutes up to 10% of the spore’s dry weight and is a hallmark of bacterial endospores.

Surrounding the core wall is the cortex, a thick layer composed primarily of peptidoglycan. Unlike the vegetative cell wall, the cortex is less cross-linked, allowing it to absorb water rapidly during germination. This layer acts as a secondary barrier, further protecting the core from mechanical and chemical stresses. The cortex also contains enzymes like cortex-lytic enzymes, which are activated during germination to degrade the cortex and facilitate the return to vegetative growth.

The outermost layers of the spore include the coat and the exosporium. The coat is a proteinaceous layer composed of over 70 different proteins arranged in an inner and outer coat. This layer is critical for spore resistance to enzymes, chemicals, and environmental stresses. It also plays a role in preventing DNA damage by acting as a physical barrier. The exosporium, present in some B. subtilis strains, is a loose-fitting, hair-like structure that provides additional protection and aids in surface adhesion. It is composed of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates, making it a versatile outer shell.

Practical applications of B. subtilis spores leverage their structural robustness. For instance, in probiotics, spores can survive the acidic conditions of the stomach, ensuring delivery to the intestines. In agriculture, spore-based biofertilizers enhance soil health by surviving harsh conditions until they reach the rhizosphere. To maximize efficacy, ensure proper storage of spore-containing products—maintain temperatures below 25°C and avoid exposure to moisture, as these factors can compromise spore viability. For laboratory work, spores can be heat-shocked at 80°C for 10 minutes to kill vegetative cells, leaving only spores for further study. Understanding the spore structure of B. subtilis not only highlights its biological ingenuity but also unlocks its potential in diverse fields.

Do Mosses Release Airborne Spores? Unveiling the Truth About Moss Reproduction

You may want to see also

Spore Function: Role of spores in B. subtilis survival and persistence

Bacillus subtilis, a ubiquitous soil bacterium, is renowned for its ability to form highly resistant endospores, often simply called spores. These structures are not just a passive survival mechanism but a sophisticated adaptation that ensures the bacterium’s persistence in harsh environments. Spores are metabolically dormant, yet genetically active, allowing them to withstand extreme conditions such as desiccation, heat, radiation, and chemical stressors. This dormancy is reversible; when conditions improve, spores can rapidly germinate and resume vegetative growth, ensuring the species’ continuity.

The formation of spores in B. subtilis is a tightly regulated, multi-stage process triggered by nutrient deprivation. As resources dwindle, the bacterium initiates sporulation, culminating in the release of a mature spore encased in a protective coat. This coat is a marvel of nature, composed of multiple layers that provide mechanical strength and chemical resistance. For instance, the outer crust layer is rich in calcium and dipicolinic acid, which confer heat resistance and protect against DNA damage. Understanding this process is crucial for industries like food preservation and biotechnology, where spore resistance poses both challenges and opportunities.

One of the most striking features of B. subtilis spores is their longevity. Studies have shown that spores can remain viable for decades, even centuries, under favorable conditions. This persistence is particularly evident in soil ecosystems, where spores act as a reservoir, ensuring the bacterium’s survival through seasonal changes and environmental fluctuations. For practical applications, such as probiotic formulations, spore stability is a key advantage. Unlike vegetative cells, spores can withstand manufacturing processes and gastrointestinal transit, making them ideal for oral delivery systems.

However, the very resilience of B. subtilis spores can also pose challenges, especially in food processing and healthcare settings. Spores can survive pasteurization temperatures (typically 72°C for 15 seconds), necessitating more aggressive sterilization methods like autoclaving (121°C for 15 minutes). In clinical contexts, spore-forming bacteria can cause infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. For example, B. subtilis is occasionally associated with bacteremia or wound infections, underscoring the importance of effective disinfection protocols.

To harness the benefits of B. subtilis spores while mitigating risks, specific strategies are employed. In probiotics, spore doses typically range from 10^6 to 10^9 CFU (colony-forming units) per serving, ensuring efficacy without overburdening the host. In industrial settings, spore-specific biocides like hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid are used to target their robust structure. For researchers, studying spore germination mechanisms offers insights into developing novel antimicrobials. By balancing respect for their resilience with targeted interventions, we can leverage the unique properties of B. subtilis spores for both preservation and innovation.

Ethanol's Power: Can 7% Concentration Effectively Kill Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Germination: Triggers and mechanisms for B. subtilis spore activation

Bacillus subtilis, a ubiquitous soil bacterium, is renowned for its ability to form highly resistant endospores, often referred to as spores. These spores can remain dormant for extended periods, withstanding extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and radiation. However, under favorable conditions, these spores can germinate, reactivating the bacterial cell’s metabolic processes. Understanding the triggers and mechanisms of spore germination in B. subtilis is crucial for applications in biotechnology, food safety, and environmental science.

Triggers for Spore Germination

Spore germination in B. subtilis is initiated by specific nutrient signals, primarily amino acids and purine nucleosides. For instance, L-valine, a branched-chain amino acid, is a potent germinant when combined with purine nucleosides like inosine or guanosine. The concentration of these germinants is critical; typically, a 10–20 mM solution of L-valine and 1–5 mM of a purine nucleoside is sufficient to trigger germination. Additionally, environmental factors such as pH (optimal around 7.5–8.0) and temperature (30–37°C) play a significant role in enhancing germination efficiency. Notably, calcium-dipicolinic acid (Ca-DPA), a spore core component, must be released for germination to proceed, marking a key transition from dormancy to metabolic activity.

Mechanisms of Spore Activation

The germination process in B. subtilis spores is tightly regulated by a series of proteins and receptors. Germinant receptors, such as GerA, GerB, and GerK, are embedded in the spore’s inner membrane and bind to specific nutrients, initiating a signaling cascade. Upon binding, these receptors activate enzymes like CwlJ, a cortex-lytic enzyme, which degrades the spore’s protective cortex layer. Simultaneously, the release of Ca-DPA from the spore core reduces core hydration, leading to rehydration and reactivation of metabolic enzymes. This mechanism ensures that germination occurs only when conditions are optimal for bacterial growth, minimizing energy waste in unfavorable environments.

Practical Applications and Considerations

Understanding spore germination in B. subtilis has practical implications for industries such as food preservation and probiotic production. For example, controlling germination triggers can help prevent spoilage in canned foods, where B. subtilis spores are common contaminants. Conversely, in probiotic formulations, optimizing germination conditions ensures the viability and efficacy of spore-based products. Researchers and practitioners should note that over-reliance on specific germinants may lead to incomplete germination, so a balanced mixture of nutrients is recommended. Additionally, monitoring environmental factors like pH and temperature is essential for consistent results.

Comparative Insights and Future Directions

Compared to other spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium or Bacillus anthracis, B. subtilis exhibits a more rapid and nutrient-specific germination response. This makes it an ideal model organism for studying spore biology. Future research could explore genetic modifications to enhance germination efficiency or develop novel germinants for targeted applications. For instance, engineering spores to germinate in response to specific environmental cues could improve their use in bioremediation or targeted drug delivery. By unraveling the intricacies of spore germination, scientists can harness the unique capabilities of B. subtilis spores for innovative solutions across diverse fields.

Mold Spores and Pleurisy: Understanding the Respiratory Health Risks

You may want to see also

Spore Applications: Uses of B. subtilis spores in industry and research

B. subtilis spores are renowned for their resilience, surviving extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, and desiccation. This durability makes them invaluable across industries and research, where stability and longevity are critical. In biotechnology, for instance, B. subtilis spores serve as robust vectors for enzyme delivery in food processing. Amylases and proteases derived from these spores are used in baking and brewing, improving dough consistency and accelerating fermentation. A typical dosage in baking applications ranges from 0.05% to 0.1% of flour weight, ensuring optimal enzymatic activity without compromising flavor.

In the pharmaceutical sector, B. subtilis spores are harnessed as probiotics and vaccine carriers. Their ability to withstand gastrointestinal conditions makes them ideal for delivering bioactive compounds to the gut. Commercial probiotic supplements often contain 1–5 billion CFU (colony-forming units) per dose, tailored for adults and children over 12. Researchers are also exploring spore-based vaccines, where antigens are displayed on spore surfaces, offering a needle-free, thermostable alternative to traditional vaccines. This approach has shown promise in preclinical trials for diseases like tuberculosis and malaria.

The agricultural industry leverages B. subtilis spores as biofertilizers and biocontrol agents. When applied to soil or seeds at rates of 1–2 kg per hectare, these spores enhance nutrient uptake and suppress pathogenic fungi like Fusarium and Rhizoctonia. Their role in promoting plant growth is particularly beneficial in organic farming, where chemical fertilizers are restricted. Field studies have demonstrated yield increases of up to 20% in crops like wheat and soybeans, coupled with reduced reliance on synthetic pesticides.

In research, B. subtilis spores serve as model systems for studying sporulation and stress resistance mechanisms. Scientists manipulate spore genetics to understand how organisms adapt to harsh environments, insights that inform astrobiology and extremophile research. For example, experiments exposing spores to simulated Martian conditions have revealed their potential to survive interplanetary travel, raising questions about panspermia. Such studies not only advance fundamental biology but also inspire innovations in space exploration and terraforming technologies.

Practical tips for utilizing B. subtilis spores include ensuring proper storage conditions—spores remain viable for years at room temperature but degrade faster in humid environments. For industrial applications, spores should be activated with nutrient-rich media before use to maximize efficacy. Whether in food, medicine, agriculture, or research, the versatility of B. subtilis spores underscores their status as a cornerstone of modern biotechnology.

Can Black Mold Spores Invade Your Appliances? What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Bacillus subtilis is a spore-forming bacterium, meaning it can produce endospores under unfavorable environmental conditions.

B. subtilis forms spores in response to nutrient depletion, particularly the lack of carbon and nitrogen sources, as a survival mechanism.

Yes, B. subtilis spores are highly resistant to heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals, allowing them to survive in extreme environments.

Yes, under favorable conditions, B. subtilis spores can germinate and return to their vegetative, actively growing state.

B. subtilis spores are widely used in biotechnology for their stability, safety, and ability to produce enzymes, probiotics, and other bioactive compounds efficiently.