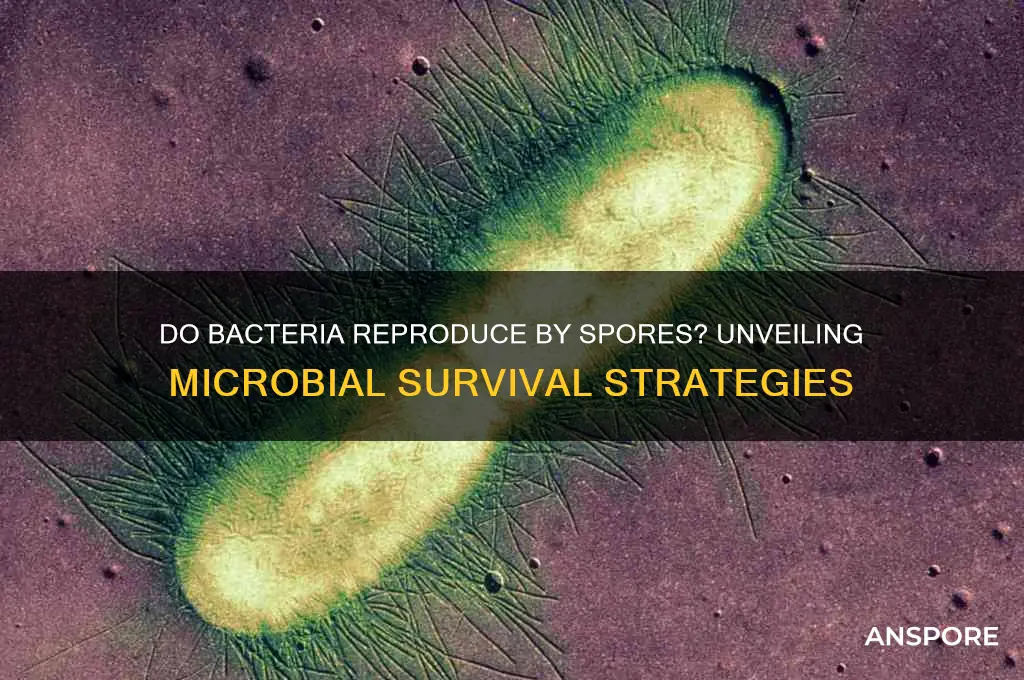

Bacteria are incredibly diverse microorganisms with various reproductive strategies, and one intriguing method is through the formation of spores. While not all bacteria reproduce this way, certain species, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, have evolved to produce highly resistant spores as a survival mechanism. These spores are not a means of reproduction in the traditional sense but rather a dormant, resilient form that allows bacteria to endure harsh environmental conditions, including extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals. When favorable conditions return, spores can germinate, reactivating the bacterial cell and enabling it to resume growth and division. This unique ability to form spores raises questions about the role of spores in bacterial reproduction and survival, making it a fascinating topic to explore in the study of microbiology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Some bacteria reproduce by forming spores, while others do not. Spore formation is a survival mechanism, not the primary method of reproduction. |

| Types of Bacteria | Primarily observed in Gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus and Clostridium species. |

| Process | Endospore formation (e.g., in Bacillus) involves the cell engulfing its DNA and cytoplasm within a protective spore coat and outer layers. |

| Function | Spores are highly resistant to extreme conditions (heat, radiation, desiccation, chemicals) and can remain dormant for years. |

| Germination | Under favorable conditions, spores germinate into vegetative cells, which then reproduce by binary fission. |

| Primary Reproduction | Most bacteria reproduce asexually via binary fission, not spore formation. Spores are for survival, not regular reproduction. |

| Examples | Bacillus anthracis (causes anthrax), Clostridium botulinum (causes botulism). |

| Significance | Spores pose challenges in sterilization processes (e.g., in food, medical, and pharmaceutical industries). |

| Detection | Spores can be detected using heat or chemical resistance tests (e.g., spore stain, autoclave survival assays). |

| Environmental Role | Spores contribute to bacterial persistence in harsh environments, aiding in species survival. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: How bacteria form spores under stress for survival in harsh conditions

- Endospore Structure: Durable, protective layers that shield bacterial DNA from extreme environments

- Germination Mechanism: Conditions and triggers that reactivate dormant spores into active bacteria

- Species Comparison: Which bacterial species reproduce via spores and their unique methods

- Environmental Role: How spore-forming bacteria impact ecosystems and human health

Sporulation Process: How bacteria form spores under stress for survival in harsh conditions

Bacteria, when faced with adverse environmental conditions such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or desiccation, employ a remarkable survival strategy known as sporulation. This process allows certain bacterial species, like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, to transform into highly resilient endospores. Unlike vegetative cells, which are vulnerable to harsh conditions, spores can remain dormant for years, even centuries, until favorable conditions return. This ability to "pause" life makes sporulation a fascinating and critical mechanism for bacterial survival.

The sporulation process begins with an asymmetric cell division, where the bacterial cell divides into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. This division is not merely a replication but a carefully orchestrated transformation. The forespore is engulfed by the mother cell, creating a double-membrane structure. Within this protective compartment, the forespore undergoes a series of morphological and biochemical changes. The DNA is compacted, and a thick, multi-layered spore coat is formed, providing resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals. The mother cell, in a selfless act, degrades its own cellular components to nourish the developing spore, ultimately lysing to release the mature spore into the environment.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporulation is crucial for industries such as food preservation and healthcare. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores can survive in canned foods and germinate under anaerobic conditions, producing deadly toxins. To prevent this, food manufacturers use high-pressure processing or temperatures exceeding 121°C (250°F) for at least 3 minutes to destroy spores. Similarly, in medical settings, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridioides difficile* pose challenges due to their resistance to standard disinfectants. Using spore-specific sterilants, such as hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid, is essential to ensure complete decontamination.

Comparatively, sporulation differs from other bacterial survival strategies, such as biofilm formation or persister cell development. While biofilms provide a communal protective matrix and persister cells enter a dormant state without morphological changes, spores are singular, highly specialized survival units. This distinction highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of sporulation as a last-resort mechanism when all other options fail. For researchers and practitioners, targeting the sporulation process—either to inhibit it in pathogens or harness it in beneficial bacteria—offers a promising avenue for innovation.

In conclusion, the sporulation process is a testament to bacterial adaptability, showcasing how microorganisms respond to stress with precision and efficiency. By forming spores, bacteria ensure their lineage’s continuity in environments that would otherwise be lethal. Whether viewed through the lens of microbiology, industry, or medicine, sporulation remains a critical phenomenon that demands both respect and strategic intervention. Understanding its intricacies not only deepens our knowledge of bacterial life but also equips us to manage its implications effectively.

Creating Lion's Mane Spore Prints: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners

You may want to see also

Endospore Structure: Durable, protective layers that shield bacterial DNA from extreme environments

Bacteria, particularly those in the genus *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, have evolved a remarkable survival strategy: the formation of endospores. These structures are not a means of reproduction but rather a dormant, highly resistant form that allows bacteria to endure extreme conditions. The endospore’s structure is a masterpiece of biological engineering, composed of multiple layers that collectively shield the bacterial DNA from heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals. Understanding this structure is key to appreciating how certain bacteria persist in environments that would destroy most other life forms.

The outermost layer of an endospore is the exosporium, a thin, proteinaceous coat that acts as the first line of defense against external stressors. Beneath this lies the spore coat, a thick, multi-layered structure composed of keratin-like proteins. This coat is exceptionally durable, providing resistance to enzymes, chemicals, and physical damage. The cortex, located beneath the spore coat, is rich in peptidoglycan and acts as a secondary barrier, further protecting the core. During endospore formation, the cortex becomes dehydrated, contributing to the spore’s resistance to heat and desiccation. These layers work in tandem to create a nearly impenetrable shield, ensuring the survival of the bacterial DNA within.

At the heart of the endospore lies the core, which contains the bacterial DNA, RNA, and essential enzymes in a highly condensed and dehydrated state. The core’s low water content and high concentration of calcium dipicolinate make it incredibly resistant to heat and radiation. This dipicolinic acid complex is a hallmark of endospores and plays a critical role in stabilizing the DNA and preventing damage. The core’s structure is so robust that endospores can remain viable for thousands of years, as evidenced by their discovery in ancient sediments and even in the gut of insects trapped in amber.

Practical applications of endospore structure knowledge are vast. For instance, in the food industry, understanding how endospores resist high temperatures informs sterilization techniques like autoclaving, which requires temperatures of 121°C (250°F) and 15 psi pressure for 15–30 minutes to ensure destruction. In healthcare, this knowledge aids in developing disinfection protocols to prevent infections caused by spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile*. Conversely, the durability of endospores is harnessed in biotechnology, where they are used as vectors for DNA storage and in the production of enzymes and biofuels under harsh conditions.

In summary, the endospore’s structure is a testament to the ingenuity of bacterial survival strategies. Its layered design—exosporium, spore coat, cortex, and core—provides unparalleled protection against extreme environments. By studying these layers, scientists can develop more effective methods to combat harmful bacteria and leverage their resilience for technological advancements. Whether in the lab, clinic, or industry, the endospore’s architecture remains a critical area of focus for both destruction and utilization.

Are Spores and Endospores Identical? Unraveling the Microbial Differences

You may want to see also

Germination Mechanism: Conditions and triggers that reactivate dormant spores into active bacteria

Bacterial spores are masters of survival, capable of enduring extreme conditions that would destroy their active counterparts. These dormant forms can persist for years, even centuries, in a state of suspended animation. However, under the right conditions, spores can germinate, reverting to active, replicating bacteria. Understanding the germination mechanism is crucial for fields like food safety, medicine, and environmental science, as it reveals how to control and prevent bacterial growth in critical scenarios.

Germination is not a spontaneous event but a highly regulated process triggered by specific environmental cues. These triggers act as signals, informing the spore that conditions are favorable for growth and replication. Key factors include nutrient availability, temperature, pH, and water content. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores require a combination of nutrients like amino acids and purine nucleosides to initiate germination. The concentration of these nutrients is critical; for example, a minimum of 1 mM L-valine is often necessary to trigger germination in *B. subtilis*.

The process begins with the activation of specific receptors on the spore’s surface, such as GerA, GerB, and GerK proteins, which bind to germinants. This binding triggers a cascade of events, including the release of dipicolinic acid (DPA) and the breakdown of the spore’s protective cortex. DPA, a calcium-chelating molecule, is a hallmark of bacterial spores and plays a role in maintaining dormancy. Its release is a key indicator that germination is underway. Water uptake is another critical step, as it rehydrates the spore’s core and reactivates metabolic processes. This phase is highly sensitive to environmental conditions; for example, spores of *Clostridium botulinum* require a minimum water activity (aw) of 0.94 to germinate, highlighting the importance of moisture control in food preservation.

Practical applications of understanding germination mechanisms are vast. In the food industry, controlling temperature, humidity, and nutrient availability can prevent spore germination in canned goods and other preserved foods. For instance, heating food to 121°C for 3 minutes (a process known as sterilization) effectively destroys spores of *Clostridium botulinum*, ensuring food safety. In medicine, targeting germination pathways could lead to novel antimicrobial strategies, particularly against spore-forming pathogens like *Bacillus anthracis*. For example, inhibitors of germinant receptors or DPA release could block germination, preventing the reactivation of dormant spores in infections.

While germination is a natural process, it is not without risks. In environmental settings, dormant spores can contaminate soil, water, and surfaces, posing long-term hazards. For instance, *Clostridium difficile* spores can survive on hospital surfaces for months, leading to healthcare-associated infections. Regular cleaning with sporicidal agents like hydrogen peroxide or chlorine-based disinfectants is essential to eliminate these spores. Additionally, understanding germination triggers can inform strategies for bioremediation, where spore-forming bacteria are used to degrade pollutants under controlled conditions.

In conclusion, the germination mechanism is a finely tuned process that transforms dormant spores into active bacteria, driven by specific environmental cues. By manipulating these conditions—whether through nutrient control, temperature adjustments, or moisture management—we can prevent unwanted germination in critical contexts. This knowledge not only safeguards food and health but also opens avenues for innovative applications in biotechnology and environmental management.

Do Gram-Negative Bacteria Form Spores? Unraveling the Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Species Comparison: Which bacterial species reproduce via spores and their unique methods

Bacterial reproduction through spores is a survival strategy employed by specific species to endure harsh environmental conditions. Unlike vegetative reproduction, which is vulnerable to extremes of temperature, desiccation, and chemicals, spore formation allows bacteria to remain dormant yet viable for extended periods. This method is not universal among bacteria; only certain species, primarily within the Firmicutes phylum, have evolved this capability. Among these, *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* are the most well-known genera. Understanding which species utilize this method and how they differ in their spore-forming processes is crucial for fields like microbiology, medicine, and food safety.

Consider *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, which forms highly resistant spores under nutrient-depleted conditions. These spores can survive in soil for decades, making them a significant concern in agricultural and bioterrorism contexts. In contrast, *Clostridium botulinum*, responsible for botulism, produces spores that thrive in anaerobic environments, such as canned foods. The sporulation process in *Bacillus* involves the formation of a thick, protective endospore within the mother cell, while *Clostridium* spores are similarly robust but often associated with toxin production during germination. These differences highlight the specialized adaptations of each species to their respective ecological niches.

From a practical standpoint, knowing which bacterial species reproduce via spores is essential for effective sterilization and disinfection. For instance, *Geobacillus stearothermophilus* is commonly used as a biological indicator in autoclave testing due to its highly heat-resistant spores. In healthcare settings, *Clostridioides difficile* spores pose a challenge in hospital environments, as they can persist on surfaces and cause recurrent infections. To combat such spores, specific protocols, such as using spore-specific disinfectants like chlorine-based solutions, are necessary. Understanding these species-specific traits ensures targeted and effective control measures.

A comparative analysis reveals that while spore formation is a shared trait, the mechanisms and environmental triggers vary significantly. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* initiates sporulation in response to nutrient deprivation, whereas *Clostridium perfringens* spores are often linked to foodborne outbreaks due to their ability to survive cooking temperatures. Additionally, *Deinococcus radiodurans*, though not a spore-former, exhibits similar resilience through DNA repair mechanisms, underscoring the diversity of bacterial survival strategies. This comparison underscores the importance of species-specific research in developing interventions tailored to each bacterium’s unique sporulation method.

In conclusion, spore-forming bacteria represent a distinct subset of species with specialized survival mechanisms. From the soil-dwelling *Bacillus* to the toxin-producing *Clostridium*, each employs unique strategies to endure adversity. Recognizing these differences is not only academically intriguing but also practically vital for industries ranging from healthcare to food preservation. By focusing on species-specific methods, we can better address the challenges posed by these resilient microorganisms.

Streptococcus vs. Coccidioides: Unraveling the Microscopic Similarities and Differences

You may want to see also

Environmental Role: How spore-forming bacteria impact ecosystems and human health

Spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, play a dual role in ecosystems and human health, acting both as environmental stabilizers and potential pathogens. These microorganisms produce highly resistant spores that can survive extreme conditions—heat, desiccation, and radiation—often persisting in soil for decades. This resilience allows them to serve as key players in nutrient cycling, breaking down organic matter and recycling nutrients like nitrogen and carbon. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores in soil contribute to the decomposition of plant material, fostering soil fertility and supporting plant growth. Without these bacteria, ecosystems would struggle to maintain the delicate balance of nutrient availability.

However, the same spores that benefit ecosystems can pose risks to human health when they enter environments where they are unwelcome. Spores of *Clostridium botulinum*, for example, can contaminate improperly canned foods, leading to botulism—a potentially fatal illness caused by the bacterium’s potent neurotoxin. Similarly, *Bacillus anthracis* spores, the causative agent of anthrax, can persist in soil for years, infecting livestock and humans through inhalation or contact. These risks highlight the importance of proper food handling and environmental monitoring. For instance, home canners should follow USDA guidelines, processing low-acid foods at 240°F (116°C) for at least 30 minutes to destroy spores, while agricultural workers in endemic areas should wear protective gear to avoid spore inhalation.

The environmental persistence of spores also makes them valuable in bioremediation, where they are harnessed to clean up pollutants. *Bacillus* species, for example, can degrade hydrocarbons in oil spills, converting toxic compounds into less harmful substances. In a 2010 study, *Bacillus* spores were applied to oil-contaminated soil, reducing hydrocarbon levels by 70% within 60 days. This application demonstrates how spore-forming bacteria can be engineered to address environmental challenges, turning a potential hazard into a solution. However, such interventions require careful management to prevent unintended consequences, such as the spread of genetically modified organisms.

Despite their ecological benefits, spore-forming bacteria can disrupt human activities when they colonize industrial settings. In hospitals, *Clostridioides difficile* spores survive routine disinfection, causing recurrent infections in vulnerable patients. Similarly, spores of *Geobacillus* species contaminate heat-sterilized food and beverages, spoiling products and incurring economic losses. To mitigate these risks, industries employ spore-specific sanitizers like hydrogen peroxide vapor or peracetic acid, which are effective at concentrations of 35% and 0.2%, respectively. For individuals, maintaining hygiene practices—such as handwashing with soap for 20 seconds—reduces spore transmission in healthcare and food preparation settings.

In conclusion, spore-forming bacteria are ecological linchpins and potential hazards, their impact shaped by context. While they sustain ecosystems through nutrient cycling and bioremediation, their resilience demands vigilance in human environments. By understanding their dual nature, we can harness their benefits while minimizing risks, ensuring they remain allies rather than adversaries in both natural and managed systems.

Are Spores Dead or Alive? Unraveling the Mystery of Their State

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Some bacteria, such as Bacillus and Clostridium, can reproduce by forming spores, but not all bacteria do so.

Bacterial spores serve as a survival mechanism, allowing bacteria to withstand harsh conditions like heat, dryness, and chemicals until favorable conditions return.

Spores are dormant, highly resistant structures, while vegetative cells are actively growing and reproducing but more vulnerable to environmental stress.

No, only certain types of bacteria, known as endospore-forming bacteria, have the ability to produce spores. Most bacteria reproduce through binary fission.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)