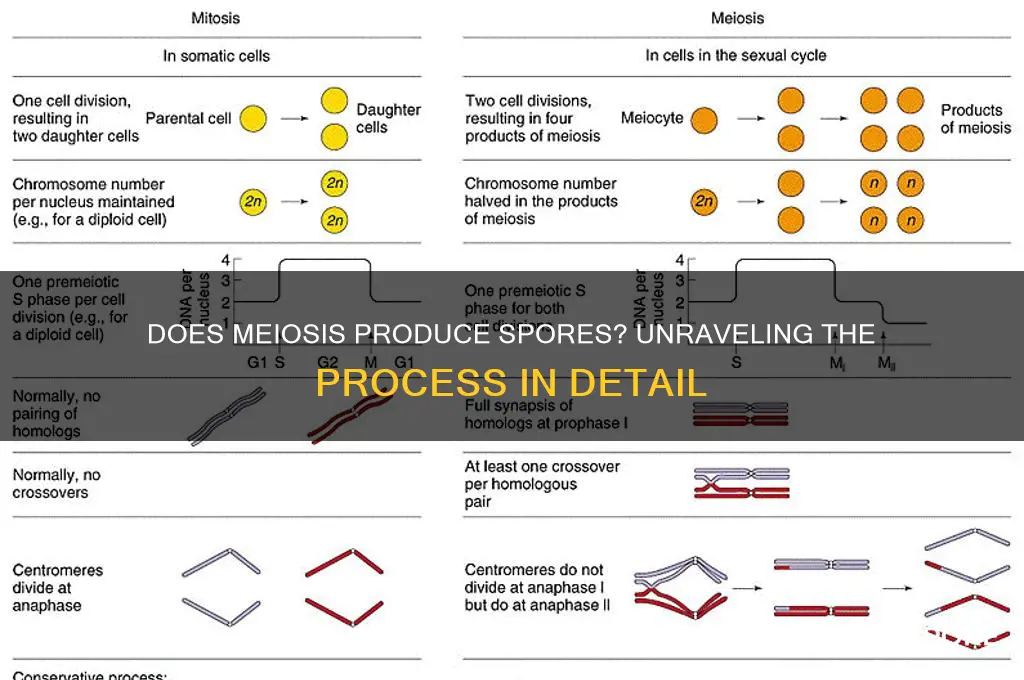

Meiosis, a specialized type of cell division, plays a crucial role in the life cycles of various organisms, particularly in the production of gametes for sexual reproduction. However, its involvement in spore formation is a topic of interest, especially in understanding the reproductive strategies of plants, fungi, and certain protists. While meiosis is primarily associated with the generation of haploid gametes, it also contributes to the development of spores in specific organisms. In plants, for instance, meiosis occurs during sporogenesis, leading to the formation of haploid spores that can develop into gametophytes. Similarly, in fungi, meiosis is essential for the production of spores, which serve as dispersal units and contribute to genetic diversity. Therefore, exploring the relationship between meiosis and spore production provides valuable insights into the reproductive mechanisms and life cycles of diverse organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does Meiosis Produce Spores? | Yes, in certain organisms like fungi, plants, and some protists. |

| Type of Meiosis | Meiosis I and Meiosis II, resulting in haploid spores. |

| Organisms Involved | Fungi (e.g., molds, mushrooms), plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), and some protists. |

| Purpose of Spore Formation | Asexual reproduction, dispersal, and survival in harsh conditions. |

| Haploid vs. Diploid | Spores are haploid (n chromosomes), while the parent cell is typically diploid (2n chromosomes). |

| Examples of Spores | Fungal spores (e.g., conidia, basidiospores), plant spores (e.g., pollen, fern spores). |

| Comparison to Gametes | Spores are not directly involved in sexual reproduction, unlike gametes (sperm and egg cells). |

| Life Cycle Role | Spores germinate into new haploid individuals or undergo further development in the life cycle. |

| Environmental Adaptation | Spores are highly resistant to extreme conditions (e.g., heat, desiccation, radiation). |

| Key Process | Sporulation (spore formation) occurs after meiosis in the life cycles of spore-producing organisms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores vs. Gametes: Distinguishing spores from gametes in meiosis outcomes

- Meiosis in Plants: Role of meiosis in spore formation in plants

- Fungal Sporulation: How meiosis contributes to fungal spore production

- Haploid vs. Diploid: Spore ploidy after meiosis in different organisms

- Life Cycles: Meiosis’s role in spore-producing life cycles (e.g., ferns)

Spores vs. Gametes: Distinguishing spores from gametes in meiosis outcomes

Meiosis, a fundamental process in biology, results in the production of specialized cells, but the outcomes—spores and gametes—serve distinct purposes. Spores are typically associated with plants, fungi, and some protists, functioning as resilient, dormant structures capable of surviving harsh conditions. Gametes, on the other hand, are sex cells (sperm and eggs) produced by animals and some plants, designed for reproduction through fertilization. Understanding the differences between these two outcomes is crucial for grasping the diversity of life cycles across organisms.

Function and Environment: A Comparative Analysis

Spores are primarily survival mechanisms. For instance, in ferns, meiosis produces haploid spores that develop into gametophytes, which then generate gametes. These spores can withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and nutrient scarcity, ensuring species continuity in adverse environments. Gametes, however, are short-lived and require immediate access to a mate for fertilization. In humans, meiosis produces four haploid gametes (sperm or eggs), each with a single mission: to fuse with another gamete and initiate embryonic development. While spores prioritize longevity and dispersal, gametes focus on genetic recombination and immediate reproductive success.

Structural and Developmental Differences

Spores are often encased in protective layers, such as the thick cell walls of fungal spores or the waterproof coats of plant spores, which enhance their durability. Gametes, in contrast, are structurally simple. Sperm cells, for example, are streamlined for motility, with a flagellum for movement, while eggs are nutrient-rich to support early embryonic growth. Developmentally, spores germinate into multicellular structures (e.g., gametophytes in plants) that later produce gametes. Gametes, once formed, bypass this intermediate step, directly participating in fertilization.

Practical Implications and Examples

For gardeners, understanding spores is essential for propagating plants like mosses or ferns, where spores are sown to grow new individuals. In agriculture, fungal spores are both a tool (e.g., in mushroom cultivation) and a threat (e.g., crop diseases). Gametes, meanwhile, are central to assisted reproductive technologies (ART) in humans and animals. Techniques like in vitro fertilization (IVF) rely on the successful collection and fusion of gametes, with success rates varying by age—for instance, women under 35 typically have a 40–50% pregnancy rate per IVF cycle, compared to 10–20% for women over 40.

Takeaway: Purpose Drives Form

The distinction between spores and gametes lies in their evolutionary roles. Spores are survivalists, adapted for endurance and dispersal, while gametes are specialists in reproduction. Meiosis produces both, but their structures, functions, and lifespans reflect their unique ecological niches. Whether in a laboratory, a garden, or the wild, recognizing these differences is key to understanding and manipulating biological processes.

Does Klebsiella Pneumoniae Form Spores? Unraveling the Truth

You may want to see also

Meiosis in Plants: Role of meiosis in spore formation in plants

Meiosis, a specialized form of cell division, is the cornerstone of spore formation in plants, particularly in ferns, mosses, and other non-seed plants. Unlike mitosis, which produces genetically identical cells, meiosis reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid cells essential for sexual reproduction. In plants, these haploid cells develop into spores, which are dispersed to initiate new generations. This process is critical for the life cycle of sporophytes (the diploid phase) and gametophytes (the haploid phase), ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability in changing environments.

Consider the life cycle of a fern as a practical example. The mature fern plant, a sporophyte, produces sporangia on the undersides of its leaves. Within these sporangia, meiosis occurs, generating haploid spores. Each spore, upon germination, grows into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte (prothallus), which is often no larger than a thumbnail. This gametophyte produces gametes (sperm and eggs) through mitosis, completing the sexual reproduction cycle. Without meiosis, this transition from sporophyte to gametophyte would be impossible, halting the plant’s reproductive process.

Analyzing the role of meiosis in spore formation reveals its dual purpose: genetic diversity and life cycle continuity. During meiosis, homologous chromosomes exchange genetic material through crossing over, introducing variations in the resulting spores. This genetic shuffling is vital for plant populations to adapt to environmental stresses, such as climate change or disease. For instance, in mosses, which are often exposed to harsh conditions, this diversity ensures that at least some spores can survive and thrive. Without meiosis, plants would lack the genetic variability needed to evolve and persist over generations.

To understand the practical implications, imagine cultivating a rare fern species in a botanical garden. To propagate it, you’d need to mimic its natural reproductive cycle, starting with spore collection. By creating humid, shaded conditions, you encourage sporangia to release spores, which can then be sown on a sterile medium. Over weeks, these spores develop into gametophytes, ready to produce the next generation. This process underscores the importance of meiosis in horticulture and conservation, as it allows for the preservation of plant species that rely on spore formation for survival.

In conclusion, meiosis is not just a biological mechanism but a lifeline for plant species that reproduce via spores. It bridges the gap between generations, ensures genetic diversity, and enables plants to colonize new habitats. Whether in a forest ecosystem or a controlled garden setting, understanding this process empowers us to protect and propagate plant life effectively. By appreciating the role of meiosis in spore formation, we gain insights into the resilience and complexity of the plant kingdom.

Understanding Spores: Haploid or Diploid? Unraveling the Genetic Mystery

You may want to see also

Fungal Sporulation: How meiosis contributes to fungal spore production

Meiosis, a specialized form of cell division, is the cornerstone of fungal sporulation, ensuring genetic diversity and survival across generations. Unlike mitosis, which produces genetically identical cells, meiosis in fungi results in haploid spores, each carrying a unique genetic makeup. This process is critical for fungi to adapt to changing environments, resist pathogens, and colonize new habitats. For instance, in *Aspergillus nidulans*, meiosis generates ascospores within sac-like structures called asci, showcasing the direct link between meiosis and spore formation.

To understand fungal sporulation, consider the steps involved in meiosis. First, fungal cells undergo DNA replication, followed by two rounds of division (Meiosis I and II). During Meiosis I, homologous chromosomes segregate, reducing the chromosome number by half. Meiosis II then divides the sister chromatids, producing four haploid nuclei. These nuclei develop into spores, often encased in protective structures like sporangia or asci. For example, in *Neurospora crassa*, meiosis occurs within a fruiting body, where haploid spores are released for dispersal. Practical tip: Observing fungal sporulation under a microscope can reveal the intricate structures formed during meiosis, such as the linear arrangement of spores in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*.

Comparatively, fungal sporulation differs from plant and animal reproduction in its reliance on external conditions to trigger meiosis. Fungi often require specific environmental cues, such as nutrient depletion or temperature shifts, to initiate sporulation. For instance, *Penicillium* species produce conidia (asexual spores) under favorable conditions but switch to meiosis-derived spores when stressed. This adaptability highlights the evolutionary advantage of meiosis in fungi, allowing them to thrive in diverse ecosystems. Caution: While meiosis is essential for spore production, not all fungal spores result from meiosis; some, like conidia, are produced mitotically.

Persuasively, the role of meiosis in fungal sporulation underscores its significance in agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology. Meiotic spores are used in fungal genetics research, such as studying gene function in *Schizosaccharomyces pombe*. Additionally, understanding sporulation helps combat fungal pathogens like *Candida albicans*, which alternates between haploid and diploid phases. Practical takeaway: Farmers can manipulate environmental conditions to control fungal sporulation, reducing crop diseases caused by spore-dispersing fungi like *Fusarium*.

Descriptively, the beauty of fungal sporulation lies in its diversity. From the powdery spores of *Claviceps purpurea* to the filamentous structures of *Mucor*, each fungus employs meiosis uniquely. For example, basidiomycetes like mushrooms produce spores on club-shaped basidia, while zygomycetes form spores within thick-walled sporangia. This variation reflects the evolutionary success of meiosis in fungi, enabling them to dominate nearly every ecosystem on Earth. Instruction: To study sporulation, cultivate fungi on agar plates with varying nutrients and observe spore formation under different conditions, noting changes in morphology and timing.

Understanding Spores: Definition, Function, and Significance in Nature

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Haploid vs. Diploid: Spore ploidy after meiosis in different organisms

Meiosis, a specialized form of cell division, reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid cells. In many organisms, this process directly results in the formation of spores, which are crucial for reproduction and survival. However, the ploidy of these spores—whether they remain haploid or undergo further changes—varies widely across different life forms. Understanding this distinction sheds light on the diverse reproductive strategies in the natural world.

Consider the life cycle of fungi, such as molds and mushrooms. After meiosis, fungi produce haploid spores, which germinate into haploid individuals. These individuals then reproduce asexually through mitosis, maintaining their haploid state until they form specialized structures that undergo meiosis again. This haploid-dominant cycle is efficient for rapid colonization of environments, as haploid organisms often require fewer resources and can reproduce quickly. For example, a single mold spore can grow into a visible colony within days under favorable conditions.

In contrast, plants exhibit a more complex alternation of generations, where both haploid and diploid phases are multicellular. Meiosis in plants produces haploid spores, which develop into gametophytes. These gametophytes then produce gametes through mitosis, and fertilization restores the diploid state in the resulting zygote. This diploid zygote grows into the sporophyte, which completes the cycle by undergoing meiosis. Notably, in ferns, each sporophyte can release thousands of spores annually, ensuring widespread dispersal and survival in diverse habitats.

Animals, including humans, follow a different pattern. Meiosis in animals produces haploid gametes (sperm and eggs), but these are not considered spores. Instead, spores are typically associated with organisms that have a multicellular haploid or diploid phase. Animals bypass the spore stage entirely, relying on direct fertilization to maintain their diploid state throughout most of their life cycle. This distinction highlights the evolutionary divergence in reproductive strategies between animals and other eukaryotes.

Practical implications of spore ploidy arise in agriculture and biotechnology. For instance, haploid plants, often derived from pollen grains, are valuable for breeding programs because they allow for faster trait selection. By doubling the chromosomes of a haploid plant (e.g., using colchicine at a dosage of 0.1% for 24 hours), researchers can create homozygous diploid lines in a single generation, significantly reducing breeding time. This technique has been applied in crops like wheat and barley to improve yield and disease resistance.

In summary, the ploidy of spores after meiosis varies across organisms, reflecting their unique life cycles and reproductive needs. While fungi and plants produce haploid spores that play central roles in their life cycles, animals bypass the spore stage altogether. Understanding these differences not only enriches our knowledge of biology but also offers practical applications in fields like agriculture and biotechnology.

Alcohol vs. Mildew: Can It Effectively Kill Spores?

You may want to see also

Life Cycles: Meiosis’s role in spore-producing life cycles (e.g., ferns)

Meiosis is the cellular process that underpins genetic diversity, and in spore-producing organisms like ferns, it plays a pivotal role in their life cycles. Unlike animals and many plants that reproduce via seeds, ferns and other spore-producing organisms rely on meiosis to create haploid spores, which are essential for their reproductive strategy. These spores are not just miniature versions of the parent plant; they are genetically unique, ensuring adaptability and survival in varying environments. This process begins in structures called sporangia, where meiotic cell division reduces the chromosome number by half, setting the stage for the next generation.

Consider the life cycle of a fern as a case study. It alternates between two distinct phases: the sporophyte (diploid) and the gametophyte (haploid). Meiosis occurs in the sporophyte generation, producing spores that develop into gametophytes. These gametophytes are small, heart-shaped structures that grow in moist environments. They, in turn, produce gametes (sperm and eggs) through mitosis. When fertilization occurs, a new sporophyte arises, completing the cycle. This alternation of generations is a hallmark of spore-producing plants and highlights meiosis as the critical step that bridges the two phases.

From a practical standpoint, understanding meiosis in spore-producing life cycles has implications for horticulture and conservation. For instance, fern enthusiasts often propagate these plants by collecting spores and cultivating gametophytes in controlled environments. Knowing that meiosis ensures genetic diversity, growers can strategically collect spores from multiple sources to enhance the resilience of their fern populations. Additionally, conservationists use this knowledge to protect endangered fern species by preserving not just mature plants but also their spore-producing structures, ensuring genetic variability in restoration efforts.

Comparatively, meiosis in spore-producing organisms differs from its role in seed-producing plants. In seed plants, meiosis is followed by fertilization and seed development, which provides protection and nutrients for the embryo. In contrast, fern spores are exposed to the environment, relying on their genetic diversity to survive. This vulnerability underscores the importance of meiosis in spore-producing life cycles, as it equips spores with the variability needed to thrive in unpredictable conditions. Without meiosis, these organisms would lack the adaptability that has allowed them to persist for millions of years.

In conclusion, meiosis is not just a biological process but a cornerstone of spore-producing life cycles, particularly in organisms like ferns. It ensures genetic diversity, facilitates alternation of generations, and supports survival in diverse environments. Whether you’re a gardener, a biologist, or simply curious about the natural world, understanding meiosis in this context offers valuable insights into the resilience and complexity of life on Earth. By appreciating its role, we can better cultivate, conserve, and marvel at these ancient plants.

Do Mushrooms Form Spores? Unveiling the Fungal Reproduction Mystery

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, meiosis produces spores only in certain organisms, such as fungi, plants, and some protists. Animals do not produce spores through meiosis.

In plants, meiosis produces haploid spores, which can develop into gametophytes. These spores are typically found in structures like sporangia.

Yes, meiosis is the process responsible for producing spores in organisms that undergo alternation of generations, as it reduces the chromosome number to create haploid cells.

No, humans and animals do not produce spores. Meiosis in these organisms produces gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction, not spores.

Organisms produce spores through meiosis as part of their life cycle to ensure genetic diversity, survive harsh conditions, and disperse to new environments. Spores are lightweight and durable, making them ideal for these purposes.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)