The question of whether metronome spore count is a relevant or measurable factor often arises in discussions surrounding fungal biology and cultivation. Metronome, typically associated with maintaining a steady tempo in music, seems unrelated to spore counting, which is a critical aspect of mycology and agriculture. However, the term metronome in this context might be a misnomer or a specific reference to a method or tool used in spore analysis. Understanding whether metronome spore count holds significance requires clarifying its definition and exploring its potential applications in fields such as fungal research, plant pathology, or biotechnology. This inquiry highlights the intersection of precision measurement and biological processes, shedding light on innovative techniques or misconceptions in spore quantification.

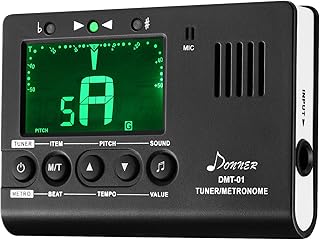

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Accuracy of metronome spore counting methods

Metronome spore counting methods have gained attention for their potential to standardize spore quantification in various industries, including pharmaceuticals and agriculture. However, the accuracy of these methods hinges on several critical factors. One key consideration is the consistency of metronome timing, as even slight deviations can lead to significant errors in spore counts. For instance, a metronome set to 60 beats per minute (BPM) must maintain precise intervals to ensure that each beat corresponds accurately to a spore count. In practice, this requires calibration and regular verification of the metronome’s timing mechanism to minimize variability.

Another factor influencing accuracy is the operator’s ability to synchronize their counting with the metronome’s rhythm. Studies have shown that human error, such as missing beats or double-counting, can introduce discrepancies of up to 10–15% in spore counts. To mitigate this, operators should undergo training to develop a steady hand-eye coordination and focus. Additionally, using visual aids, like a flashing light synchronized with the metronome, can enhance accuracy by providing a dual sensory cue. For optimal results, operators should practice counting at different BPM settings (e.g., 50, 60, 70 BPM) to adapt to varying rhythms.

Comparative analysis reveals that metronome spore counting is most accurate when combined with automated systems. Manual methods, while cost-effective, are prone to fatigue and inconsistency over prolonged periods. In contrast, integrating metronome timing with digital counters or image analysis software can achieve precision levels of ±2%. For example, in pharmaceutical spore viability testing, automated systems using metronome-guided intervals have demonstrated 98% accuracy in counting *Bacillus subtilis* spores at concentrations of 10^6 CFU/mL. This hybrid approach balances efficiency and reliability, making it ideal for high-stakes applications.

Despite its advantages, metronome spore counting is not without limitations. Environmental factors, such as humidity and temperature, can affect spore dispersion and settling rates, skewing counts. For instance, in humid conditions (>70% relative humidity), spores may clump together, leading to undercounting. To address this, samples should be prepared in controlled environments (20–25°C, 40–60% humidity) and agitated gently before counting. Furthermore, the method is less effective for spores smaller than 1 μm, as their movement may not align well with metronome beats. In such cases, alternative techniques like flow cytometry may be more suitable.

In conclusion, the accuracy of metronome spore counting methods depends on meticulous attention to timing, operator skill, and environmental control. While manual methods offer accessibility, automated integration significantly enhances precision. By adhering to best practices—such as regular metronome calibration, operator training, and controlled sample preparation—users can maximize the reliability of this technique. For industries requiring stringent spore quantification, combining metronome timing with advanced technologies provides a robust solution, ensuring consistent and accurate results.

Do Spores Contain Embryos? Unraveling the Mystery of Plant Reproduction

You may want to see also

Factors affecting spore count reliability

Spore count reliability is a critical aspect of mycology and microbiology, yet it’s surprisingly fragile. Environmental factors like humidity, temperature, and air quality can skew results dramatically. For instance, a 5% increase in relative humidity can double spore germination rates in some species, while temperatures above 30°C may denature spore proteins, rendering them uncountable. To ensure accuracy, maintain a controlled environment: use HEPA filters to reduce airborne contaminants, keep humidity between 40–60%, and stabilize temperatures at 22–25°C during sampling and counting.

Consider the sampling method itself—a seemingly minor detail that can introduce major errors. Swabbing surfaces with sterile nylon swabs captures only 70–80% of spores compared to vacuum-based methods, which are more efficient but risk over-collection. For air sampling, use a volumetric spore trap calibrated to 28.3 L/min for 5 minutes to ensure consistency. Always replicate samples in triplicate to account for variability, and clean equipment with 70% ethanol between uses to prevent cross-contamination.

The age and viability of spores also play a pivotal role in count reliability. Spores older than 6 months may lose viability, reducing detectable counts by up to 40%. To mitigate this, store spore suspensions in a desiccator at 4°C and refresh stocks every 3 months. When working with dormant spores, pre-treat samples with 0.1% Tween 80 to break surface tension and enhance dispersal, improving count accuracy by 20–30%.

Human error remains an overlooked but significant factor. Inconsistent staining techniques, such as over- or under-diluting spore suspensions, can lead to false negatives or positives. Follow a standardized protocol: dilute samples 1:100 in sterile water, apply 0.5 mL to a hemocytometer, and count spores under 400x magnification. Train personnel rigorously—studies show that untrained individuals misidentify spores 30% of the time, while trained technicians achieve 95% accuracy.

Finally, the choice of growth medium can distort spore counts, particularly in mixed-species samples. Nutrient-rich agar may favor fast-growing species, overshadowing slower ones. Use selective media like malt extract agar for fungi or nutrient agar with antibiotics for bacteria to isolate target spores. For precise quantification, incorporate a viability assay: treat spores with 1 mg/mL fluorescein diacetate for 10 minutes to distinguish live (fluorescent) from dead spores, improving count reliability by 15–20%.

By addressing these factors—environment, sampling method, spore age, human error, and growth medium—you can significantly enhance the reliability of spore counts. Each step, though small, contributes to a robust and reproducible process, essential for both research and industrial applications.

Can Spores Survive in Space? Exploring Microbial Life's Cosmic Resilience

You may want to see also

Comparing manual vs. automated counting techniques

Manual spore counting, often performed using a hemocytometer or petri dish, relies on human precision and visual acuity. Technicians dilute spore suspensions, load the sample, and count under a microscope, typically in a grid pattern. This method demands meticulous technique to avoid overcounting or missing spores, especially in dense suspensions. For instance, a 1:100 dilution might yield 30-50 spores per square, requiring the technician to extrapolate to calculate colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL). While cost-effective and accessible, manual counting introduces variability due to human error, fatigue, and subjective interpretation of spore morphology.

Automated spore counting systems, such as flow cytometers or image analysis software, streamline the process by leveraging technology for consistency and speed. Flow cytometers, for example, detect spores based on size, granularity, and fluorescence, providing real-time counts with minimal user intervention. A typical protocol involves staining spores with a viability dye (e.g., SYBR Green) and running the sample through the instrument at a controlled flow rate, such as 50 μL/min. These systems reduce human bias and handle high-throughput applications efficiently. However, they require significant upfront investment and specialized training to troubleshoot calibration or clogging issues.

When comparing accuracy, automated systems often outperform manual methods, particularly in complex samples with debris or varying spore sizes. For instance, a study comparing manual hemocytometer counts to automated image analysis found a 15-20% discrepancy in favor of the automated method due to its ability to distinguish spores from contaminants. However, manual counting remains valuable for low-resource settings or when verifying automated results, as it allows for direct visual inspection of spore integrity.

Practical considerations further differentiate the two techniques. Manual counting requires sterile technique and careful dilution to avoid overloading the counting chamber, while automated systems necessitate regular maintenance, such as cleaning flow cells or updating software algorithms. For small-scale applications, a manual approach using a $50 hemocytometer may suffice, whereas large-scale pharmaceutical or environmental labs benefit from investing in a $50,000 flow cytometer for precision and scalability.

Ultimately, the choice between manual and automated counting hinges on the specific needs of the application. Manual methods offer simplicity and affordability but sacrifice speed and consistency, making them ideal for educational settings or preliminary assays. Automated systems excel in high-stakes environments requiring reproducibility and throughput, such as vaccine production or air quality monitoring. By understanding these trade-offs, researchers can select the technique that best aligns with their goals, ensuring accurate and reliable spore counts.

Are Spores and Endospores Identical? Unraveling the Microbial Differences

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Applications in fungal research and agriculture

Fungal spores are microscopic powerhouses, each capable of developing into a new organism under the right conditions. Accurately counting these spores is crucial in both research and agriculture, where understanding fungal populations directly impacts outcomes. In research, spore counts help scientists study fungal growth rates, pathogenicity, and responses to environmental changes. In agriculture, they guide disease management strategies, ensuring crops remain healthy and productive. While traditional methods like hemocytometers and microscopy are reliable, they can be time-consuming and prone to human error. This is where innovative tools like metronome-based systems come into play, offering precision and efficiency in spore quantification.

Consider the application of metronome spore counting in studying mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with plant roots. Researchers often need to quantify spore density in soil samples to assess fungal colonization rates. A metronome-based system, calibrated to dispense a controlled volume of spore suspension, can streamline this process. For instance, a study might require counting spores in a 1 mL soil extract. By using a metronome to standardize the dilution and counting process, researchers can achieve consistent results, reducing variability across experiments. This precision is particularly valuable when comparing fungal populations across different soil types or treatments.

In agriculture, metronome spore counting can revolutionize disease monitoring and biocontrol strategies. For example, farmers combating powdery mildew, a common fungal disease in grapes, can use spore counts to determine the optimal timing for fungicide application. A metronome-based system could be integrated into automated spore samplers, providing real-time data on spore concentrations in the air. If spore counts exceed a threshold—say, 10 spores per cubic meter of air—the system could trigger an alert, prompting immediate action. This proactive approach minimizes crop damage and reduces reliance on chemical treatments, aligning with sustainable farming practices.

However, implementing metronome spore counting in agriculture requires careful calibration and validation. Factors like spore size, shape, and environmental conditions can influence accuracy. For instance, smaller spores, such as those of *Botrytis cinerea*, may require finer calibration than larger spores like *Aspergillus*. Farmers and researchers should also account for external variables, such as humidity and temperature, which can affect spore viability and dispersion. Regular maintenance and cross-validation with traditional methods are essential to ensure reliable results.

In conclusion, metronome spore counting offers a versatile tool for advancing fungal research and agricultural practices. Its ability to provide precise, consistent measurements can enhance our understanding of fungal dynamics and improve disease management strategies. By integrating this technology into existing workflows, scientists and farmers can achieve greater efficiency and accuracy, ultimately fostering healthier ecosystems and more productive crops. Whether in the lab or the field, the metronome’s rhythmic precision may well set the beat for the future of fungal studies.

Did Ferns Lose Spores? Unraveling the Mystery of Fern Reproduction

You may want to see also

Challenges in standardizing spore count procedures

Standardizing spore count procedures is fraught with challenges, particularly when considering the variability in spore types, environmental conditions, and methodologies. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores, commonly found in indoor environments, require different sampling techniques compared to *Bacillus* spores used in pharmaceutical testing. This disparity complicates the creation of a universal protocol. Additionally, environmental factors such as humidity, temperature, and air flow significantly influence spore dispersion and viability, making it difficult to establish consistent baseline conditions across different settings. Without standardized controls for these variables, results can vary widely, undermining the reliability of spore counts.

One major hurdle in standardization is the lack of universally accepted sampling methods. Direct microscopy, air sampling, and surface swabs are commonly used, but each has limitations. For example, air sampling devices like the Andersen Impactor are effective for airborne spores but may undercount heavier spores that settle quickly. Conversely, surface swabs can miss airborne spores entirely. The choice of method often depends on the specific application, such as assessing indoor air quality versus validating sterilization processes. Without a consensus on which method is most appropriate for different scenarios, standardization remains elusive.

Another challenge lies in the interpretation of spore count data. Thresholds for acceptable spore levels vary by industry and application. For instance, the pharmaceutical industry may require spore counts below 1 CFU/m³ in cleanrooms, while indoor air quality guidelines might allow up to 500 spores/m³ for common molds. These discrepancies make it difficult to develop a single, universally applicable standard. Furthermore, the biological variability of spores—such as their ability to remain dormant for extended periods—adds complexity to data interpretation, as dormant spores may not be detected by standard viability assays.

Practical implementation of standardized procedures is also hindered by resource constraints. High-precision equipment like laser particle counters or PCR-based identification systems can provide accurate spore counts but are costly and require specialized training. Smaller laboratories or facilities in developing regions may rely on less accurate, more affordable methods, leading to inconsistencies in data. Additionally, the lack of global regulatory oversight means that even when standards exist, enforcement and adherence vary widely, further complicating efforts to standardize spore count procedures.

To address these challenges, a multi-faceted approach is necessary. First, industry-specific guidelines should be developed to account for the unique needs of different applications. Second, investment in accessible, standardized equipment and training programs can help bridge the resource gap. Finally, international collaboration among regulatory bodies, researchers, and industry stakeholders is essential to establish and enforce consistent protocols. While standardization remains a complex endeavor, these steps can pave the way for more reliable and comparable spore count data across diverse settings.

Can Spores Grow in Stool? Understanding Microbial Growth in Feces

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A metronome spore count refers to the measurement of the number of spores present in a sample, typically used in microbiology to assess the concentration of fungal or bacterial spores. It is often used in environmental monitoring, food safety, and pharmaceutical industries.

A metronome spore count is typically performed using a spore count method, such as the pour plate or spread plate technique. A known volume of the sample is plated onto a nutrient agar medium, incubated, and the resulting colonies are counted to estimate the number of spores present in the original sample.

Yes, metronome spore count can significantly affect the accuracy of microbial analysis. An inaccurate spore count can lead to incorrect estimations of microbial populations, potentially compromising the quality and safety of products in industries such as food, pharmaceuticals, and environmental monitoring. Proper sampling, handling, and analysis techniques are crucial to ensuring accurate metronome spore counts.