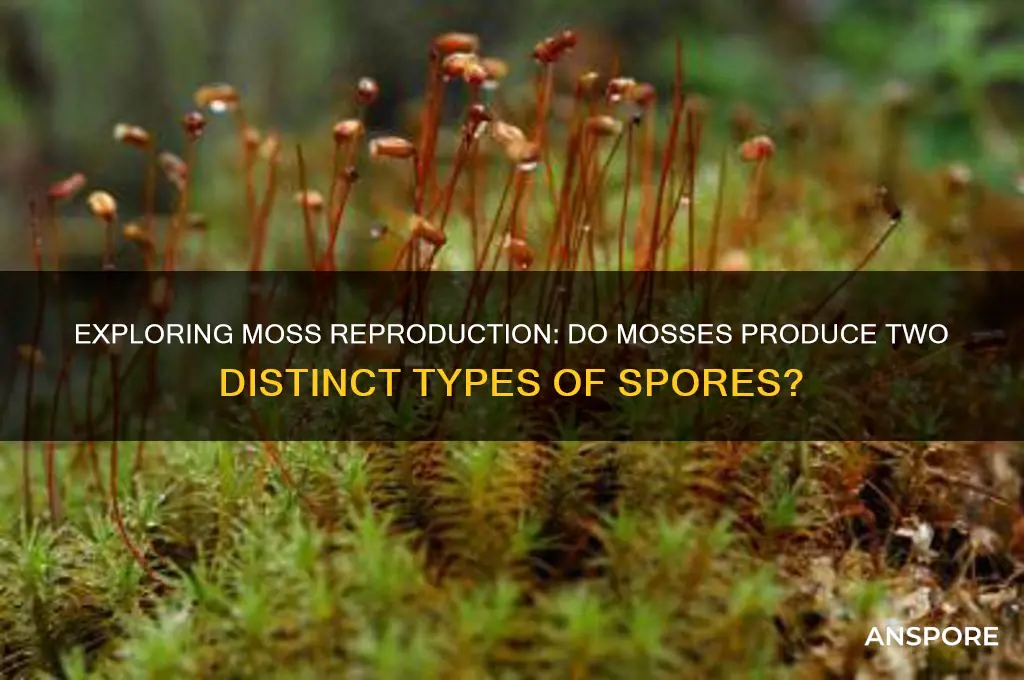

Mosses, a diverse group of non-vascular plants, exhibit a unique life cycle characterized by alternation of generations, where both haploid gametophytes and diploid sporophytes play distinct roles. A fascinating aspect of their reproductive biology is the production of spores, which are crucial for dispersal and survival. Interestingly, some moss species are known to produce two different types of spores: macrospores and microspores. These spores differ in size and function, with macrospores typically developing into female gametophytes and microspores into male gametophytes. This phenomenon, known as heterospory, is a specialized adaptation that enhances reproductive efficiency and success in certain moss lineages. Understanding the presence and significance of these two spore types sheds light on the evolutionary strategies and ecological roles of mosses in their environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Types of Spores | Mosses produce two distinct types of spores: haploid spores (n) and diploid spores (2n). However, the more accurate distinction is between male spores (microspores) and female spores (megaspores), which are both haploid. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Spores are produced during the sporophyte generation of the moss life cycle, which is the diploid phase. |

| Function | Spores serve as the dispersal and reproductive units of mosses, allowing them to colonize new habitats. |

| Size Difference | Microspores (male) are generally smaller than megaspores (female), though the size difference is less pronounced compared to seed plants. |

| Development | Microspores develop into male gametophytes (antheridia), while megaspores develop into female gametophytes (archegonia). |

| Germination | Spores germinate into protonema, a filamentous or thalloid structure that eventually develops into the gametophyte. |

| Genetic Composition | Both types of spores are haploid (n), containing a single set of chromosomes. |

| Ecological Role | Spores are crucial for survival and adaptation, enabling mosses to thrive in diverse environments, including moist and shady habitats. |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals, ensuring wide distribution and colonization. |

| Taxonomic Significance | The presence of two spore types is a key characteristic distinguishing mosses from other bryophytes and vascular plants. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Moss Life Cycle Overview: Alternation of generations, gametophyte dominant, sporophyte dependent, spores key to reproduction

- Types of Moss Spores: Differentiating between male (microspores) and female (megaspores) spores in moss reproduction

- Sporophyte Structure: Capsule and seta, spore production site, development from fertilized egg

- Spore Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid in spreading moss spores to new habitats

- Homosporous vs. Heterosporous: Most mosses homosporous, some primitive species show heterosporous traits, producing two spore types

Moss Life Cycle Overview: Alternation of generations, gametophyte dominant, sporophyte dependent, spores key to reproduction

Mosses, unlike many plants, do not produce seeds. Instead, they rely on spores for reproduction, a process that hinges on the alternation of generations. This life cycle is a fascinating dance between two distinct phases: the gametophyte and the sporophyte. The gametophyte, the dominant and long-lived generation, is what we typically recognize as moss—the green, carpet-like structure. It produces gametes (sex cells) and is haploid, meaning it has a single set of chromosomes. The sporophyte, on the other hand, is short-lived and dependent on the gametophyte for nutrients. It grows from the fertilized egg and is diploid, with two sets of chromosomes. This sporophyte produces spores, which are dispersed to start new gametophytes, completing the cycle.

The key to understanding moss reproduction lies in the spores. Mosses produce two types of spores: haploid spores that develop into gametophytes. These spores are not differentiated by sex; rather, they grow into gametophytes that can produce both male and female reproductive organs. The male organs release sperm, which, with the help of water, swim to the female organs to fertilize the egg. This fertilization results in the growth of the sporophyte, which then produces new spores through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number back to haploid. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in moss populations.

To observe this process, consider a practical example: *Sphagnum* moss, commonly found in peat bogs. Its gametophytes are lush and green, while its sporophytes are small, capsule-like structures atop slender stalks. When mature, these capsules release spores into the wind, which can travel significant distances before landing and germinating into new gametophytes. For enthusiasts or educators, collecting and observing these spores under a microscope can reveal their intricate structures, typically measuring between 10 to 30 micrometers in diameter. This hands-on approach deepens understanding of the spore’s role in the moss life cycle.

A critical takeaway is the dependency of the sporophyte on the gametophyte. Unlike vascular plants, where the sporophyte is dominant, moss sporophytes lack true roots, stems, and leaves. They remain attached to and nourished by the gametophyte throughout their short lives. This dependency highlights the gametophyte’s central role in the moss life cycle and underscores why mosses thrive in moist environments—water is essential for sperm mobility during fertilization. For gardeners or conservationists, maintaining consistent moisture levels is crucial when cultivating mosses or preserving their habitats.

In summary, the moss life cycle is a masterclass in simplicity and efficiency. Alternation of generations ensures genetic diversity, while the dominance of the gametophyte and dependency of the sporophyte reflect evolutionary adaptations to specific environments. Spores, as the reproductive linchpin, are both tiny and mighty, capable of dispersing widely to colonize new areas. Whether you’re a botanist, hobbyist, or nature enthusiast, understanding this cycle offers insights into the resilience and beauty of these ancient plants. Practical tips, like observing *Sphagnum* under a microscope or ensuring moist conditions for moss cultivation, make this knowledge tangible and applicable.

Understanding Spore-Forming Bacteria: Survival Mechanisms and Health Implications

You may want to see also

Types of Moss Spores: Differentiating between male (microspores) and female (megaspores) spores in moss reproduction

Mosses, unlike many plants, exhibit a fascinating reproductive strategy involving two distinct types of spores: microspores and megaspores. These spores are not just different in name; they play unique and critical roles in the moss life cycle. Microspores, often referred to as male spores, are smaller and produced in greater quantities. They develop into male gametophytes, which ultimately generate sperm cells. In contrast, megaspores, the female counterparts, are larger and fewer in number. They grow into female gametophytes, responsible for producing egg cells. This sexual dimorphism in spore production is a key adaptation that ensures genetic diversity and reproductive success in mosses.

To differentiate between microspores and megaspores, one must observe their size, quantity, and the structures that produce them. Microspores are typically produced in microsporangia, located on the male gametophyte, while megaspores develop within megasporangia on the female gametophyte. A practical tip for identification is to examine the sporophyte under a microscope: microspores are usually 10–30 micrometers in diameter, whereas megaspores can range from 30 to 100 micrometers. Additionally, the ratio of microspores to megaspores is often skewed, with microspores outnumbering megaspores by a significant margin, reflecting their distinct roles in fertilization.

Understanding the differentiation between these spores is crucial for anyone studying moss reproduction or cultivating mosses. For instance, in moss gardening, knowing which spores are present can help predict the sex ratio of the gametophytes, influencing the overall health and diversity of the moss colony. To collect spores for observation, gently tap mature sporophytes onto a piece of paper and use a magnifying glass or microscope to inspect the spores. For educational purposes, labeling the spores with their respective sizes and functions can aid in clearer identification.

From an evolutionary perspective, the separation of spores into male and female types is a remarkable adaptation. It allows mosses to optimize resource allocation, ensuring that the smaller, more numerous microspores can travel farther to locate megaspores, while the larger megaspores provide ample nutrients for the developing embryo. This division of labor enhances the efficiency of moss reproduction, particularly in environments where water—essential for sperm motility—may be scarce. By studying these differences, researchers gain insights into the evolutionary strategies of non-vascular plants and their resilience in diverse ecosystems.

In conclusion, the distinction between microspores and megaspores is not merely a biological curiosity but a fundamental aspect of moss reproduction. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or enthusiast, recognizing these differences enriches your understanding of moss biology and its ecological significance. Practical observation techniques and awareness of spore characteristics can turn a simple moss patch into a living laboratory, revealing the intricate mechanisms that sustain these ancient plants.

Can Mold Reproduce Through Spores? Understanding Mold's Survival Mechanism

You may want to see also

Sporophyte Structure: Capsule and seta, spore production site, development from fertilized egg

Mosses, unlike more complex plants, do not produce seeds but rely on spores for reproduction. Central to this process is the sporophyte structure, which emerges from a fertilized egg and develops into a capsule supported by a seta. This structure is where spore production occurs, ensuring the continuation of the moss life cycle. The capsule, often likened to a tiny urn, houses the spores, while the seta acts as a slender stalk, elevating the capsule to facilitate spore dispersal.

The development of the sporophyte begins with the fusion of male and female gametes, resulting in a diploid zygote. This zygote grows into an embryonic sporophyte, which remains dependent on the gametophyte (the leafy moss plant) for nutrients and water. As the sporophyte matures, it differentiates into the seta and capsule. The seta, a simple yet vital structure, elongates to raise the capsule above the moss cushion, optimizing spore release. This elevation is crucial for wind-mediated dispersal, a primary mechanism for mosses to colonize new habitats.

Within the capsule, spore production takes place in specialized structures called sporangia. Here, meiosis reduces the chromosome number, producing haploid spores. The capsule’s walls often feature a peristome, a ring of teeth-like structures that regulate spore release in response to environmental conditions, such as humidity. This mechanism ensures spores are dispersed efficiently, increasing the likelihood of successful germination. The peristome’s design varies among moss species, reflecting adaptations to specific ecological niches.

Understanding the sporophyte structure offers practical insights for moss cultivation and conservation. For enthusiasts growing moss in gardens or terrariums, ensuring adequate moisture and airflow supports seta and capsule development. Additionally, observing the capsule’s maturity—often indicated by a change in color or texture—signals the optimal time for spore collection. For conservationists, protecting habitats that foster sporophyte growth is critical, as spore production is essential for maintaining genetic diversity in moss populations.

In summary, the sporophyte’s capsule and seta are not merely anatomical features but functional units integral to moss reproduction. From the fertilized egg’s development to the precise mechanisms of spore release, these structures exemplify the elegance of moss biology. By appreciating their role, we can better cultivate, conserve, and study these remarkable plants.

Do Fungal Spores Contain Endosperm? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid in spreading moss spores to new habitats

Mosses, unlike many plants, do not produce seeds but rely on spores for reproduction. These spores are remarkably lightweight, often measuring just a few micrometers in diameter, making them ideal for dispersal by natural elements. Wind, the most common agent, carries spores over vast distances, especially in open environments. For instance, a single moss capsule can release thousands of spores, each capable of traveling miles if conditions are right. This method ensures that mosses can colonize new habitats far from their parent plants, increasing their chances of survival in diverse ecosystems.

Water plays a secondary but equally vital role in spore dispersal, particularly in moist environments. Moss spores are hydrophobic, allowing them to float on water surfaces without becoming waterlogged. In rainforests or near water bodies, spores can be carried by streams, rain droplets, or even dew, eventually settling in damp, shaded areas where moss thrives. This method is especially effective for species like *Sphagnum* moss, which often grows in wetlands. To maximize water dispersal, gardeners and conservationists can mimic natural conditions by placing moss fragments near water sources or using misting systems to simulate rain.

Animals, though less obvious, are another key player in spreading moss spores. Small creatures like insects, snails, and birds inadvertently carry spores on their bodies as they move through moss-covered areas. For example, a beetle crawling on a moss mat can pick up spores on its exoskeleton and deposit them elsewhere. Even larger animals, such as deer or rodents, can transport spores on their fur. This method is particularly effective in dense forests where wind dispersal is limited. Encouraging biodiversity in moss habitats can thus enhance spore dispersal, making it a practical tip for moss cultivation or restoration projects.

Each dispersal method has its advantages and limitations. Wind is efficient for long-distance travel but relies on unpredictable weather patterns. Water dispersal is highly effective in specific environments but is localized. Animal-aided dispersal is slower but ensures spores reach microhabitats that might otherwise be inaccessible. Understanding these mechanisms allows for strategic interventions, such as placing moss near wind corridors or water pathways, to promote growth in desired areas. By harnessing these natural processes, one can facilitate the spread of moss spores and support their ecological role in stabilizing soil and retaining moisture.

Can Dettol Effectively Eliminate Fungal Spores? A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Homosporous vs. Heterosporous: Most mosses homosporous, some primitive species show heterosporous traits, producing two spore types

Mosses, like many plants, reproduce via spores, but the story doesn’t end there. Most moss species are homosporous, meaning they produce a single type of spore that develops into a bisexual gametophyte capable of producing both male and female reproductive organs. This simplicity aligns with the majority of bryophytes, reflecting an evolutionary strategy that has proven effective for their survival in diverse environments. However, a fascinating deviation exists: some primitive moss species exhibit heterosporous traits, producing two distinct spore types—microspores and megaspores—that develop into male and female gametophytes, respectively. This rarity in mosses mirrors a more complex reproductive strategy seen in seed plants, raising questions about evolutionary transitions in plant reproduction.

To understand the significance of heterosporous mosses, consider the genus *Sphagnum*, which, while primarily homosporous, has species like *Sphagnum contortum* that show heterosporous tendencies under specific environmental conditions. These exceptions are not mere anomalies but clues to the evolutionary pressures that might have driven the development of heterosporous traits. Heterospory is energetically costly, requiring the plant to allocate resources to producing two spore types, yet it offers advantages such as reduced competition between male and female gametophytes and increased efficiency in fertilization. For gardeners or researchers cultivating moss, identifying heterosporous traits could provide insights into optimizing growth conditions or studying evolutionary biology.

From a practical standpoint, distinguishing between homosporous and heterosporous mosses requires careful observation of spore size and gametophyte development. Homosporous mosses produce spores of uniform size, typically ranging from 8 to 20 micrometers in diameter, while heterosporous species exhibit dimorphism, with microspores often half the size of megaspores. For enthusiasts or educators, collecting and examining moss spores under a microscope can reveal these differences, offering a hands-on way to explore plant diversity. Additionally, documenting environmental factors such as moisture levels, light exposure, and substrate type can help correlate conditions with reproductive strategies, providing valuable data for both scientific research and horticultural applications.

The rarity of heterosporous traits in mosses underscores their evolutionary significance. While most mosses thrive with a homosporous strategy, the existence of heterosporous species suggests a potential evolutionary bridge to more complex plant forms. For instance, heterosporous mosses may offer insights into the origins of seed plants, which rely on similar reproductive mechanisms. By studying these primitive species, scientists can trace the evolutionary pathways that led to the diversification of plant life. For the casual observer, this highlights the remarkable adaptability of mosses, reminding us that even in the smallest organisms, complexity and innovation abound.

In conclusion, while most mosses adhere to a homosporous reproductive strategy, the presence of heterosporous traits in some species provides a window into the evolutionary dynamics of plant reproduction. Whether you’re a researcher, gardener, or enthusiast, understanding these differences enriches your appreciation of moss biology and its broader implications. By observing spore characteristics and environmental influences, you can contribute to the growing body of knowledge about these ancient plants, bridging the gap between simplicity and complexity in the natural world.

Spore on Mac: Which Version Do You Really Need?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, mosses produce two different types of spores: haploid spores (produced in the capsule of the sporophyte) and diploid spores are not typically discussed, as the primary distinction is between the haploid spores and the gametophyte/sporophyte generations.

Mosses primarily produce haploid spores from the sporophyte generation. There isn’t a second distinct type of spore; instead, the life cycle alternates between the gametophyte (haploid) and sporophyte (diploid) phases.

No, mosses do not have male and female spores. Instead, they have haploid spores that develop into gametophytes, which can be either male (producing sperm) or female (producing eggs).

Mosses primarily produce sexual spores (haploid) through the sporophyte stage. While some mosses can reproduce asexually via fragments or gemmae, these are not considered spores but rather vegetative structures.