Nocardia, a genus of Gram-positive, aerobic bacteria, is known for its filamentous growth and ability to cause infections in humans and animals. While Nocardia shares some morphological similarities with spore-forming bacteria, such as Actinomyces, it does not produce spores under normal conditions. Instead, Nocardia reproduces through fragmentation of its filamentous structures, forming rod-shaped cells that can disseminate and establish infections. This distinction is crucial in understanding its pathogenesis and differentiating it from other spore-forming pathogens. However, under specific environmental stresses, some studies suggest Nocardia may exhibit spore-like structures, though this remains a subject of ongoing research and debate.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spores Production | Yes, Nocardia species produce spores. |

| Type of Spores | Aerospore-like structures (not true spores but spore-like elements). |

| Function of Spores | Aid in survival under adverse conditions (e.g., desiccation, heat). |

| Morphology | Filamentous, branching, Gram-positive, partially acid-fast bacteria. |

| Habitat | Soil, water, and organic matter; opportunistic pathogen in humans. |

| Disease Association | Causes nocardiosis, primarily in immunocompromised individuals. |

| Antibiotic Susceptibility | Sensitive to sulfonamides, amikacin, and imipenem. |

| Colony Appearance | Dry, chalky, and filamentous colonies on agar plates. |

| Cell Wall Composition | Contains mycolic acids, contributing to partial acid-fastness. |

| Metabolism | Aerobic, chemoorganotrophic, and slow-growing. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Nocardia's reproductive mechanisms

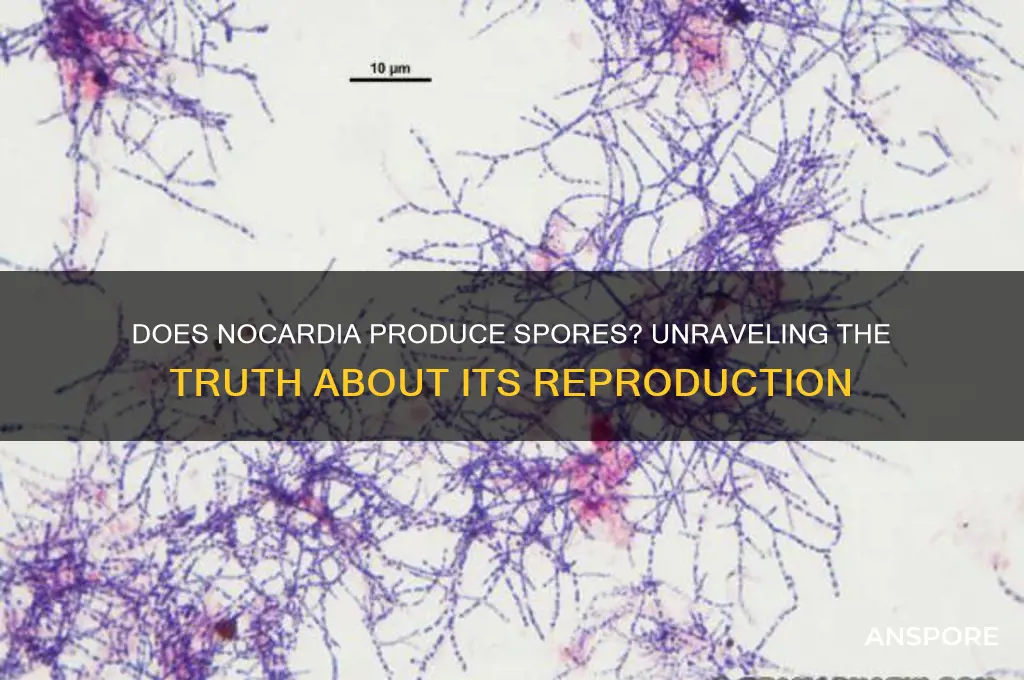

Nocardia, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, employs a unique reproductive strategy that sets it apart from many other bacteria. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Bacillus or Clostridium, Nocardia does not produce endospores as a means of survival under harsh conditions. Instead, its reproductive mechanisms are primarily focused on vegetative growth and fragmentation, which allow it to thrive in diverse environments, including soil and human tissues.

Vegetative Growth and Fragmentation

Nocardia reproduces through binary fission, a process where a single cell divides into two identical daughter cells. This method is efficient in favorable conditions but is not a survival mechanism during stress. Additionally, Nocardia exhibits a filamentous growth pattern, forming long, branching hyphae that resemble fungal structures. These hyphae can fragment into smaller segments, each capable of growing into a new bacterial colony. This fragmentation is a key reproductive mechanism, enabling Nocardia to disperse and colonize new areas. For example, in soil, fragmented hyphae can spread through water or wind, ensuring the bacterium’s persistence in its natural habitat.

Environmental Adaptation Without Spores

The absence of spore formation in Nocardia raises questions about its survival strategies. Instead of relying on spores, Nocardia adapts through metabolic versatility and robust cell wall composition. Its waxy cell wall, rich in mycolic acids, provides resistance to desiccation and environmental stressors. This adaptation allows Nocardia to endure harsh conditions without the need for spore formation. For instance, in clinical settings, Nocardia’s ability to survive in macrophages highlights its resilience, even in the human immune system.

Clinical Implications of Reproductive Mechanisms

Understanding Nocardia’s reproductive mechanisms is crucial in clinical contexts, particularly in treating nocardiosis, an infection caused by Nocardia species. The bacterium’s filamentous growth and fragmentation can lead to tissue invasion and dissemination, complicating treatment. Antibiotics such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) are commonly used, with dosages ranging from 15–20 mg/kg/day of trimethoprim for adults. However, the bacterium’s ability to fragment and persist in tissues necessitates prolonged therapy, often lasting 6–12 months, to prevent relapse.

Comparative Analysis with Spore-Forming Bacteria

Comparing Nocardia to spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus anthracis reveals distinct survival strategies. While Bacillus forms highly resistant spores that can remain dormant for years, Nocardia relies on active growth and fragmentation. This difference has practical implications: spore-forming bacteria require extreme measures (e.g., autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes) for eradication, whereas Nocardia is more susceptible to standard disinfection methods due to its lack of spores. However, its ability to fragment and persist in tissues poses unique challenges in infection control.

Practical Tips for Managing Nocardia Infections

For healthcare providers, recognizing Nocardia’s reproductive mechanisms is essential for effective management. In immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV or on corticosteroids, early diagnosis and prompt initiation of TMP-SMX are critical. Monitoring for treatment response and adjusting dosages based on renal function (e.g., reducing TMP-SMX dosage in patients with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min) can improve outcomes. Additionally, educating patients about environmental exposure risks, such as gardening or construction work, can help prevent infections, as Nocardia is commonly found in soil.

Do Mold Spores Fall to the Floor? Understanding Airborne Fungal Movement

You may want to see also

Sporulation process in Nocardia

Nocardia, a genus of Gram-positive, aerobic actinomycetes, has long been recognized for its complex life cycle and pathogenic potential. While it is primarily known for causing nocardiosis in immunocompromised individuals, its ability to produce spores remains a topic of scientific inquiry. Contrary to some bacteria that readily form spores under stress, Nocardia’s sporulation process is less straightforward and varies among species. This variability complicates both its identification and clinical management, making it essential to understand the nuances of its sporulation behavior.

The sporulation process in Nocardia is not as well-defined as in spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus or Clostridium. Some species, such as *Nocardia asteroides* and *Nocardia brasiliensis*, have been observed to produce spore-like structures under specific environmental conditions, such as nutrient deprivation or desiccation. These structures, often referred to as "sporangiospores," are not true endospores but rather modified cells that enhance survival in harsh environments. The formation of these structures involves cellular differentiation, where vegetative cells undergo morphological changes, including thickening of the cell wall and reduction in metabolic activity. This process is energy-intensive and typically occurs as a last resort for survival rather than a routine part of the life cycle.

From a practical standpoint, understanding Nocardia’s sporulation process has implications for disinfection and sterilization protocols. While Nocardia is generally susceptible to heat and chemical disinfectants, its spore-like forms may exhibit increased resistance. For instance, in healthcare settings, standard autoclaving (121°C for 15–20 minutes) is effective against vegetative cells but may require longer exposure times to ensure eradication of spore-like structures. Similarly, in laboratory settings, researchers must account for the potential presence of these forms when culturing or storing Nocardia strains, as they can remain viable for extended periods in adverse conditions.

Comparatively, Nocardia’s sporulation process differs significantly from that of true spore-formers like Bacillus anthracis, which produce highly resistant endospores. While Bacillus spores are characterized by their ability to withstand extreme temperatures, radiation, and chemicals, Nocardia’s spore-like structures are less resilient. This distinction is crucial in clinical and industrial contexts, where misidentification of Nocardia as a true spore-former could lead to inadequate sterilization measures. For example, in pharmaceutical manufacturing, where spore-forming bacteria are a major concern, Nocardia’s limited sporulation capacity may reduce its risk as a contaminant but still necessitates vigilance.

In conclusion, while Nocardia does not produce true spores, its ability to form spore-like structures under stress highlights its adaptability and survival strategies. This process, though less efficient than true sporulation, has significant implications for infection control, laboratory practices, and environmental persistence. By understanding the sporulation process in Nocardia, clinicians, researchers, and industry professionals can better manage its risks and ensure effective eradication when necessary. Practical tips include using prolonged heat treatment for sterilization, incorporating spore-specific tests in diagnostic workflows, and maintaining stringent aseptic techniques when handling Nocardia cultures.

Do Spores Spark Growth? Unveiling the Science Behind Their Potential

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for spore formation

Nocardia, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, is known for its ability to produce spores under specific environmental conditions. While not all species within the genus are spore-formers, those that do exhibit this trait rely on environmental triggers to initiate the process. Understanding these triggers is crucial for controlling Nocardia’s survival and dissemination in various settings, from clinical environments to natural ecosystems.

Analytical Insight: Spore formation in Nocardia is primarily driven by nutrient deprivation, particularly the depletion of carbon and nitrogen sources. When these essential elements become scarce, the bacteria enter a dormant state by forming spores, which are highly resistant to harsh conditions such as desiccation, heat, and chemicals. For instance, studies have shown that Nocardia asteroides, a common species, initiates sporulation when glucose levels drop below 0.05% in culture media. This adaptive mechanism ensures survival in environments where resources are unpredictable or limited.

Instructive Guidance: To induce spore formation in a laboratory setting, researchers can manipulate environmental conditions such as pH, temperature, and oxygen availability. A pH range of 6.5 to 7.5 and temperatures between 25°C and 37°C are optimal for Nocardia sporulation. Additionally, reducing oxygen levels by using anaerobic jars or gas mixtures can accelerate the process. For practical applications, such as studying spore resistance, gradually decreasing nutrient concentrations over 7–10 days while maintaining these conditions yields consistent results.

Comparative Perspective: Unlike Bacillus or Clostridium, which sporulate in response to extreme environmental stress, Nocardia’s spore formation is more gradual and tied to subtle changes in nutrient availability. This distinction highlights the importance of understanding species-specific triggers. For example, while Bacillus subtilis sporulates rapidly under starvation, Nocardia species require prolonged exposure to low-nutrient conditions, emphasizing the need for tailored experimental designs when studying these organisms.

Descriptive Example: In natural environments, Nocardia spores are often found in soil, where nutrient availability fluctuates seasonally. During dry periods, when organic matter decomposes slowly, Nocardia species may sporulate to survive until conditions improve. This ecological adaptation allows them to persist in diverse habitats, from arid deserts to temperate forests. Observing these patterns in the field can provide insights into the role of environmental triggers in spore formation and the broader implications for microbial ecology.

Persuasive Takeaway: Recognizing the environmental triggers for Nocardia spore formation is not just an academic exercise—it has practical implications for infection control and antimicrobial strategies. Spores’ resistance to standard disinfectants means that healthcare settings must employ specialized cleaning protocols, such as using sporicides like hydrogen peroxide vapor or chlorine dioxide, to prevent outbreaks. By understanding these triggers, we can develop more effective methods to manage Nocardia’s persistence in both natural and clinical environments.

Can You Safely Dispose of Fungal Spores Down the Drain?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Comparison with spore-forming bacteria

Nocardia, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, stands apart from spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium in its survival strategies. While spore-forming bacteria produce highly resistant endospores that can withstand extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and radiation, Nocardia relies on filamentous growth and robust cell wall structures for persistence in harsh environments. This fundamental difference in survival mechanisms influences their ecological niches, pathogenicity, and susceptibility to antimicrobial agents.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these distinctions is crucial in clinical and laboratory settings. For instance, spore-forming bacteria require stringent sterilization methods, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, to ensure complete eradication. In contrast, Nocardia, though not spore-forming, can survive in soil and water due to its filamentous nature, necessitating thorough disinfection protocols but not the extreme measures needed for spores. This highlights the importance of tailoring infection control practices to the specific biology of the organism.

Analytically, the absence of spore formation in Nocardia has implications for its role in infections. Unlike spore-forming pathogens, which can remain dormant for years before causing disease, Nocardia infections typically arise from environmental exposure and are less likely to recur due to latent spores. However, Nocardia’s ability to form branching filaments allows it to evade host immune responses, contributing to chronic and difficult-to-treat infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. This contrasts with the acute, often severe, infections caused by spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium difficile.

Persuasively, the comparison underscores the need for targeted therapeutic approaches. While spore-forming bacteria may require combination therapies, including spore-specific antibiotics like vancomycin or fidaxomicin, Nocardia infections are primarily treated with drugs that penetrate its complex cell wall, such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or linezolid. Clinicians must recognize these differences to optimize treatment outcomes, especially in vulnerable populations like those with HIV/AIDS or organ transplant recipients.

In conclusion, while Nocardia and spore-forming bacteria share a capacity for environmental resilience, their distinct survival mechanisms dictate unique challenges in detection, prevention, and treatment. By focusing on these differences, healthcare professionals and researchers can develop more effective strategies to manage infections caused by these organisms, ultimately improving patient care and public health outcomes.

Inoculating Rye Grain: Which Spore Cultures Are Safe and Effective?

You may want to see also

Clinical implications of Nocardia spores

Nocardia, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, is known for its ability to produce spores under certain conditions. These spores, though less commonly discussed than those of Bacillus or Clostridium, have significant clinical implications, particularly in immunocompromised patients. Understanding the role of Nocardia spores is crucial for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nocardiosis, a potentially severe infection.

From an analytical perspective, Nocardia spores contribute to the bacterium's survival in harsh environments, such as dry or nutrient-depleted conditions. This resilience allows Nocardia to persist in soil and water, increasing the likelihood of human exposure. Clinically, this means that patients with occupational or recreational soil contact, such as farmers or gardeners, are at higher risk of infection. For healthcare providers, recognizing this environmental reservoir is essential for risk stratification, especially in patients with underlying conditions like HIV, organ transplantation, or long-term corticosteroid use.

Instructively, the presence of Nocardia spores complicates diagnostic procedures. Traditional culture methods may require extended incubation periods, as spores can take longer to germinate and grow. Clinicians should be aware that initial negative cultures do not rule out nocardiosis, particularly in disseminated infections. Molecular techniques, such as PCR, can improve detection speed and accuracy, but their availability may be limited in resource-constrained settings. For suspected cases, repeated sampling and close collaboration with microbiologists are recommended to ensure accurate diagnosis.

Persuasively, the clinical management of Nocardia infections must account for the bacterium's spore-forming capacity. Treatment regimens typically involve prolonged courses of antibiotics, often lasting 6–12 months, to eradicate both actively growing bacteria and dormant spores. Sulfonamides, particularly trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, remain the cornerstone of therapy, but resistance is increasingly reported. Combination therapy with agents like imipenem, amikacin, or linezolid may be necessary for severe or refractory cases. Adherence to treatment is critical, as premature discontinuation can lead to relapse, especially if spores remain viable.

Comparatively, Nocardia spores differ from those of other spore-forming pathogens in their clinical relevance. Unlike Bacillus anthracis or Clostridium difficile, Nocardia spores are not typically associated with large-scale outbreaks or toxin-mediated disease. However, their ability to cause chronic, progressive infections in vulnerable hosts underscores their importance. For instance, Nocardia spores can disseminate to the central nervous system, leading to brain abscesses that require surgical intervention in addition to prolonged antibiotic therapy. This contrasts with infections caused by non-spore-forming bacteria, which may respond more rapidly to treatment.

Descriptively, the clinical implications of Nocardia spores extend to prevention strategies. Immunocompromised patients should be educated about avoiding exposure to soil and dust, particularly in endemic areas. Personal protective equipment, such as gloves and masks, can reduce inhalation or inoculation of spores during high-risk activities. In healthcare settings, prompt identification and isolation of infected patients are essential to prevent nosocomial transmission. Additionally, environmental decontamination measures, though challenging due to the spores' hardiness, can play a role in reducing exposure in high-risk populations.

In conclusion, Nocardia spores are a critical but often overlooked aspect of nocardiosis. Their environmental persistence, diagnostic challenges, and treatment complexities necessitate a tailored clinical approach. By understanding the unique implications of these spores, healthcare providers can improve patient outcomes and mitigate the risks associated with this opportunistic pathogen.

C. Diff Spores Survival: How Long Do They Live on Surfaces?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Nocardia is known to produce spores, specifically called nocardiospores, which are aerial, filamentous, and resistant to harsh environmental conditions.

Nocardia produces nocardiospores, which are a type of asexual spore formed at the tips or along the aerial hyphae of the organism.

Yes, Nocardia spores can be infectious to humans, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, as they can survive in the environment and cause nocardiosis upon inhalation.

Nocardia spores enhance the organism's survival by providing resistance to desiccation, heat, and other environmental stresses, allowing it to persist in soil and other habitats until favorable conditions return.