Rock snot, scientifically known as *Didymosphenia geminata*, is a species of freshwater diatom that has gained attention due to its invasive nature and impact on aquatic ecosystems. Unlike many other organisms, rock snot does not produce spores; instead, it reproduces asexually through the fragmentation of its stalks, which allows it to spread rapidly in suitable environments. This diatom forms thick, brownish mats on rocks and other submerged surfaces, altering habitats and potentially disrupting local food webs. Understanding its reproductive mechanisms is crucial for managing its spread and mitigating its ecological effects.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Rock Snot Identification: Distinguish rock snot from other algae, focusing on its unique characteristics and growth patterns

- Spore Formation in Algae: Explore whether algae species, including rock snot, produce spores for reproduction

- Rock Snot Life Cycle: Analyze the stages of rock snot’s life cycle to determine spore presence or absence

- Environmental Impact: Investigate how rock snot spreads without spores and its ecological effects on waterways

- Scientific Research Findings: Review studies on rock snot to confirm or deny spore-related reproductive mechanisms

Rock Snot Identification: Distinguish rock snot from other algae, focusing on its unique characteristics and growth patterns

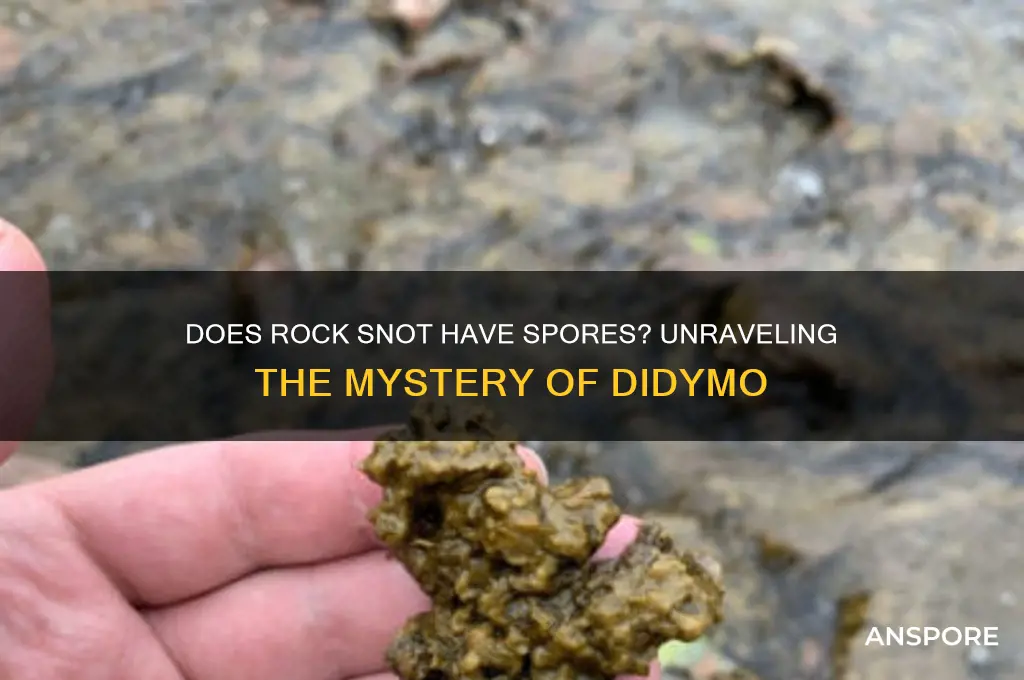

Rock snot, scientifically known as *Didymosphenia geminata*, is a freshwater diatom that stands out from other algae due to its distinctive growth patterns and physical characteristics. Unlike typical algae, which often form thin, green films or floating mats, rock snot creates thick, brownish, mucus-like mats that adhere stubbornly to rocks, submerged vegetation, and even fishing gear. This slimy texture and its ability to smother surfaces are key identifiers. While some algae produce spores, rock snot reproduces primarily through the fragmentation of its stalks, allowing it to spread rapidly in suitable conditions. Understanding these unique traits is essential for accurate identification and management.

To distinguish rock snot from other algae, observe its growth structure. Rock snot forms dense, carpet-like mats that can be several centimeters thick, often with a woolly or fibrous appearance. These mats are composed of long, branching stalks that anchor the diatoms to surfaces. In contrast, common green algae like *Cladophora* tend to form softer, more delicate filaments or clumps. Another distinguishing feature is rock snot’s color, which ranges from pale brown to yellowish-brown, unlike the vibrant greens of many algae species. If you encounter a slimy, brown mat in a freshwater stream or river, especially in areas with low nutrient levels and high water clarity, rock snot is a likely culprit.

Practical identification tips include examining the texture and tenacity of the growth. Rock snot mats are remarkably resilient and can be difficult to remove from surfaces, often requiring significant force. Additionally, rock snot thrives in cold, nutrient-poor waters, whereas most algae prefer warmer, nutrient-rich environments. If you’re unsure, collect a sample and examine it under a microscope; rock snot’s diatom cells are distinct, with a unique, boat-like shape. Avoid touching or disturbing suspected rock snot without proper precautions, as its fragments can easily spread to new locations via water currents or contaminated equipment.

While rock snot does not produce spores, its ability to spread through fragmentation makes early detection critical. Regularly inspect fishing gear, waders, and boats after use in infested waters, cleaning them thoroughly to prevent accidental transport. Unlike spore-producing organisms, rock snot’s dispersal relies heavily on human activity and natural water flow. By focusing on its unique growth patterns and environmental preferences, you can effectively differentiate rock snot from other algae and take appropriate steps to limit its spread. Accurate identification is the first line of defense in managing this invasive species.

Do Coccus Bacteria Form Spores? Unraveling Their Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Spore Formation in Algae: Explore whether algae species, including rock snot, produce spores for reproduction

Rock snot, scientifically known as *Didymosphenia geminata*, is a type of freshwater diatom notorious for forming thick, brownish mats in rivers and streams. Unlike many algae, diatoms are unique in their reproductive strategies. While some algae species produce spores as part of their life cycle, diatoms like *D. geminata* reproduce primarily through cell division, forming new frustules (silica cell walls) within the parent cell. This asexual method allows for rapid colonization under favorable conditions, but it raises the question: does rock snot, or any diatom, produce spores for reproduction?

To explore this, it’s essential to distinguish between spore formation in algae and the reproductive mechanisms of diatoms. True spores, such as those produced by certain green algae or fungi, are specialized cells designed for dispersal and survival in harsh conditions. Diatoms, however, lack this spore-forming capability. Instead, they rely on their silica frustules for protection and their ability to form resting stages called "auxospores" under stress. Auxospores are not true spores but rather enlarged cells that allow diatoms to regenerate their silica walls and resume growth when conditions improve. This distinction is critical for understanding why rock snot does not produce spores in the traditional sense.

Comparatively, other algae species, such as *Chlamydomonas* or *Zygnema*, do produce spores as part of their life cycle. For instance, zygotes in some green algae develop thick walls to become zygospores, which can remain dormant until environmental conditions trigger germination. This spore-forming ability provides a survival advantage in fluctuating habitats. In contrast, rock snot’s reliance on asexual reproduction and auxospore formation reflects its adaptation to stable freshwater environments, where rapid growth and colonization are more advantageous than long-term dormancy.

For those studying or managing rock snot, understanding its reproductive limitations is practical. Since *D. geminata* does not produce spores, control efforts should focus on preventing the spread of live cells rather than dormant spore-like structures. Measures such as cleaning fishing gear, avoiding disturbance of infested areas, and monitoring water quality can effectively limit its expansion. Additionally, recognizing the absence of spores in diatoms helps differentiate rock snot from spore-producing algae, aiding in accurate identification and targeted management strategies.

In conclusion, while spore formation is a common reproductive strategy in many algae species, rock snot and other diatoms do not produce spores. Their reliance on asexual reproduction and auxospore formation highlights their unique adaptations to freshwater ecosystems. This knowledge not only clarifies the biology of *D. geminata* but also informs practical approaches to managing its spread, ensuring that efforts are both accurate and effective.

Can Spores Grow in Your Lungs? Understanding the Risks and Facts

You may want to see also

Rock Snot Life Cycle: Analyze the stages of rock snot’s life cycle to determine spore presence or absence

Rock snot, scientifically known as *Didymosphenia geminata*, is a freshwater diatom infamous for its invasive tendencies and ability to form thick, brown mats on riverbeds. To determine whether spores play a role in its life cycle, we must dissect the stages of its development. Unlike fungi or certain plants, *D. geminata* reproduces primarily through cell division, producing clones of itself. This asexual reproduction occurs when individual diatom cells divide within their silica cell walls, eventually splitting into two new cells. While this process is efficient for rapid colonization, it does not involve spores. Instead, the organism relies on the dispersal of these daughter cells, which can be carried downstream by water currents, to establish new populations.

Analyzing the life cycle further, *D. geminata* also has a sexual reproduction phase, though it is less common. During this stage, two cells fuse to form a zygote, which develops into a resting spore called an auxospore. This auxospore is not a true spore in the traditional sense, as it does not serve as a dormant, dispersal-focused structure. Instead, it is a temporary stage that allows the diatom to grow into a larger cell, breaking free from the constraints of its silica cell wall. This process is crucial for genetic diversity but does not involve the production of spores for long-distance dispersal or survival in harsh conditions.

A comparative analysis of rock snot’s life cycle with other organisms reveals why the absence of spores is significant. For instance, fungi like mold rely on spores for both reproduction and survival, allowing them to persist in unfavorable environments. In contrast, *D. geminata* depends on water flow for dispersal, making it highly dependent on its aquatic habitat. This distinction highlights the organism’s vulnerability to environmental changes, such as reduced water flow or pollution, which can disrupt its ability to spread.

To determine spore presence or absence in rock snot’s life cycle, one must focus on its reproductive mechanisms. Practical tips for identification include examining water samples under a microscope to observe cell division and auxospore formation. While auxospores may resemble spores superficially, their function and role in the life cycle differ significantly. For researchers and environmental managers, understanding this distinction is crucial for developing strategies to control rock snot’s spread without mistakenly targeting nonexistent spore-based dispersal mechanisms.

In conclusion, rock snot’s life cycle does not involve spores in the traditional sense. Its primary mode of reproduction is asexual cell division, supplemented by a rare sexual phase producing auxospores. This knowledge is essential for accurately addressing the ecological impact of *D. geminata* and designing effective management strategies. By focusing on its unique reproductive biology, we can better combat its invasive spread and protect freshwater ecosystems.

Can You Play Spore on Mobile? A Complete Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Impact: Investigate how rock snot spreads without spores and its ecological effects on waterways

Rock snot, scientifically known as *Didymosphenia geminata*, is a freshwater diatom that forms thick, brownish mats on riverbeds, altering aquatic ecosystems. Unlike many organisms, it does not rely on spores for reproduction. Instead, it spreads through the fragmentation of its stalks, which are easily transported by water currents, fishing gear, or even wading boots. This asexual method allows it to colonize new areas rapidly, particularly in nutrient-poor, cold-water environments. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for managing its spread and mitigating its ecological impact.

The ecological effects of rock snot on waterways are profound and multifaceted. Its dense mats smother the riverbed, reducing habitat availability for invertebrates and altering the food web. For instance, insects like mayflies and stoneflies, which are critical food sources for fish, struggle to survive in affected areas. This disruption cascades up the food chain, impacting fish populations and, consequently, anglers and wildlife that depend on them. Studies in New Zealand and North America have shown declines in trout populations in rivers heavily infested with rock snot, underscoring its threat to biodiversity and recreational fisheries.

Preventing the spread of rock snot requires targeted, practical measures. Anglers and recreational users can minimize transmission by cleaning and drying their equipment thoroughly before moving between water bodies. For example, soaking gear in a 2% bleach solution for 10 minutes or freezing it for 24 hours can effectively kill diatom cells. Regulatory bodies should also implement monitoring programs to detect early infestations, as eradication becomes significantly more challenging once rock snot establishes itself. Public education campaigns, particularly in high-risk areas, are essential to raise awareness and foster responsible behavior.

Comparatively, rock snot’s spread without spores highlights a unique challenge in invasive species management. Unlike spore-producing organisms, which can be airborne or widely dispersed, rock snot’s reliance on physical transport means human activity plays a disproportionate role in its dispersal. This makes it both a problem and an opportunity: while human behavior accelerates its spread, targeted interventions can effectively curb it. By focusing on high-traffic areas like popular fishing spots and implementing strict biosecurity protocols, communities can significantly reduce its impact on waterways.

In conclusion, rock snot’s spore-free spread and ecological consequences demand proactive, informed action. Its ability to fragment and travel via human activity underscores the need for individual responsibility and systemic interventions. By understanding its biology and implementing practical measures, we can protect vulnerable waterways and preserve the delicate balance of aquatic ecosystems. The fight against rock snot is not just about controlling an invasive species—it’s about safeguarding the health of our rivers and the life they support.

Chlamydomonas Spores: Understanding Their Haploid or Diploid Nature

You may want to see also

Scientific Research Findings: Review studies on rock snot to confirm or deny spore-related reproductive mechanisms

Rock snot, scientifically known as *Didymosphenia geminata*, is a freshwater diatom that forms dense, mucus-like mats on riverbeds, raising concerns about its ecological impact. A critical question in understanding its proliferation is whether it reproduces via spores. Recent studies have systematically investigated this, employing molecular biology, microscopy, and ecological modeling to assess the presence of spore-like structures or mechanisms. Initial findings suggest that *D. geminata* primarily reproduces asexually through cell division, with no evidence of spore formation in its life cycle. However, some researchers propose that its resilient extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) may act similarly to spores, enabling long-term survival in adverse conditions.

To confirm or deny spore-related mechanisms, a 2021 study published in *Harmful Algae* analyzed *D. geminata* samples from 20 global river systems. Using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), researchers examined cell morphology and EPS composition, finding no structures resembling spores. Instead, the EPS matrix was identified as the key to its persistence, trapping sediment and nutrients to support colony growth. This aligns with earlier work in *Freshwater Biology* (2018), which highlighted the EPS’s role in anchoring cells to substrates, rather than facilitating dispersal via spores. These studies collectively challenge the spore hypothesis, emphasizing the importance of EPS in *D. geminata*’s reproductive strategy.

A comparative analysis in *Aquatic Ecology* (2020) further explored whether *D. geminata*’s dispersal mechanisms could be misinterpreted as spore-like. By tracking cell movement in controlled flumes, researchers observed that fragmentation of the EPS matrix allowed cells to detach and colonize new areas. This process, termed "clonal dispersal," mimics spore-like behavior but lacks the genetic recombination associated with true spores. The study concluded that while *D. geminata* does not produce spores, its EPS-mediated dispersal is highly efficient, contributing to its invasive success in nutrient-poor environments.

From a practical standpoint, understanding *D. geminata*’s reproductive mechanisms has direct implications for management strategies. For instance, efforts to control rock snot outbreaks often focus on reducing nutrient inputs, as the diatom thrives in low-nutrient waters. However, targeting the EPS matrix could offer a novel approach. A 2022 pilot study in *Water Research* tested the efficacy of enzymatic treatments to degrade EPS, reducing mat formation by 70% within 14 days. This suggests that disrupting EPS synthesis or stability may be more effective than traditional methods, which often fail to prevent recolonization.

In conclusion, scientific research overwhelmingly denies the presence of spores in *D. geminata*’s reproductive cycle. Instead, its EPS matrix emerges as the central driver of persistence and dispersal, challenging earlier assumptions about spore-like mechanisms. By refocusing on EPS-targeted interventions, managers can develop more precise and sustainable strategies to mitigate rock snot’s ecological impact. This shift underscores the importance of rigorous, evidence-based research in addressing environmental challenges.

Cordyceps Spore Spread: How This Fungus Infects and Propagates

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, rock snot (Didymosphenia geminata) is a type of freshwater diatom that reproduces through cell division, not spores.

Rock snot spreads through the dispersal of its microscopic cells, often via water currents, animals, or human activities like fishing gear and boating.

Yes, rock snot forms colonies by attaching to rocks and substrates using stalks, growing through asexual reproduction and cell division.

No, rock snot lacks spore-like structures; it reproduces by releasing motile cells that settle and grow into new colonies.

Its filamentous, stalked structure and rapid growth can resemble spore-producing organisms, but it relies solely on cell division for reproduction.

![Shirayuri Koji [Aspergillus oryzae] Spores Gluten-Free Vegan - 10g/0.35oz](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61ntibcT8gL._AC_UL320_.jpg)