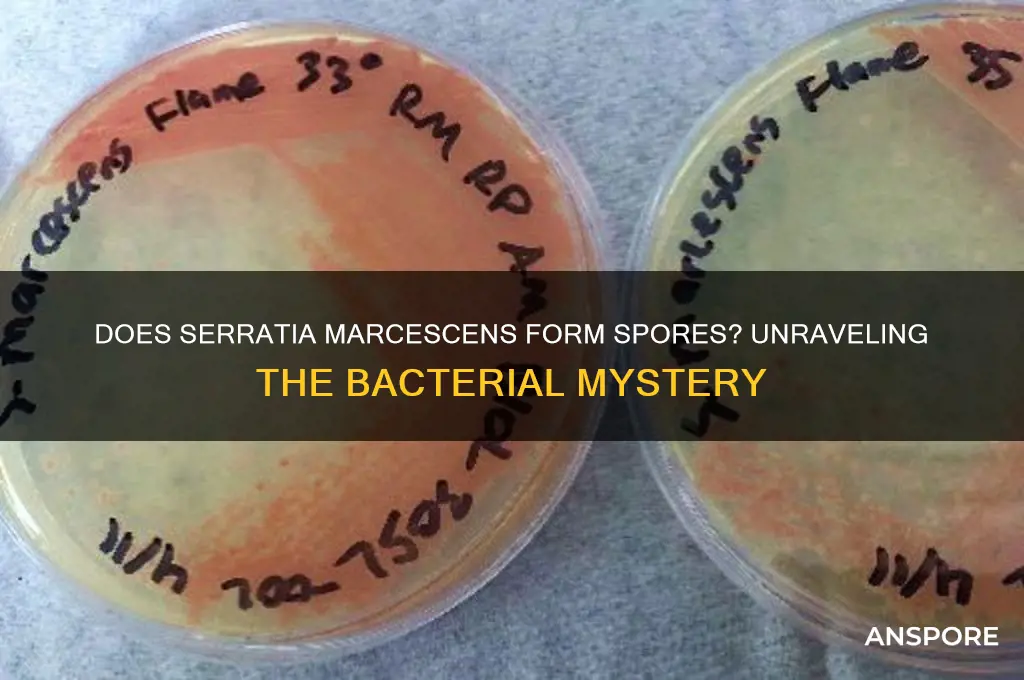

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium known for its distinctive red pigmentation, is often found in various environments, including soil, water, and clinical settings. While it is a well-studied organism, there is ongoing interest in its survival mechanisms, particularly whether it forms spores. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Bacillus or Clostridium, Serratia marcescens is not classified as a sporulating bacterium. Instead, it relies on other strategies, such as biofilm formation and resistance to desiccation, to endure harsh conditions. Understanding its survival mechanisms is crucial, as S. marcescens can cause opportunistic infections in humans, and its ability to persist in diverse environments contributes to its clinical significance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does Serratia marcescens form spores? | No |

| Reason | Serratia marcescens is a non-spore-forming, Gram-negative bacterium. |

| Reproduction | Reproduces through binary fission, a form of asexual reproduction where the cell divides into two identical daughter cells. |

| Survival mechanisms | Can survive in various environments due to its ability to produce pigments (e.g., prodigiosin) and form biofilms, but not through spore formation. |

| Relevance | Its non-spore-forming nature is important in clinical and environmental settings, as spores are typically more resistant to disinfection and sterilization methods. |

| Sources | Recent studies and reviews (up to 2023) consistently confirm that Serratia marcescens does not form spores. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Conditions: Does S. marcescens require specific environmental triggers to initiate spore formation

- Spore Morphology: Are S. marcescens spores distinguishable from other bacterial spores in structure

- Survival Mechanisms: How do S. marcescens spores withstand harsh conditions compared to vegetative cells

- Genetic Factors: Are there specific genes in S. marcescens responsible for spore formation

- Clinical Implications: Do S. marcescens spores impact infection persistence or treatment resistance

Sporulation Conditions: Does S. marcescens require specific environmental triggers to initiate spore formation?

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium known for its distinctive red pigmentation, has long intrigued microbiologists with its survival strategies. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Bacillus and Clostridium, S. marcescens does not produce endospores under standard laboratory conditions. However, recent studies suggest that certain environmental stressors may trigger a spore-like dormant state, raising questions about the specific conditions required for this phenomenon. Understanding these triggers could provide insights into its resilience in diverse habitats, from healthcare settings to natural ecosystems.

To explore whether S. marcescens requires specific environmental triggers for spore-like formation, consider nutrient deprivation as a potential factor. In laboratory settings, culturing S. marcescens in minimal media with limited carbon sources, such as 0.1% glucose, has been observed to induce a dormant state characterized by reduced metabolic activity and increased resistance to heat and desiccation. This response mimics sporulation in other bacteria, though the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Researchers recommend maintaining cultures at 30°C for 7–10 days to observe these changes, as higher temperatures may inhibit the process.

Another critical trigger is oxygen availability. S. marcescens thrives in aerobic environments but can adapt to low-oxygen conditions, a trait linked to its survival in diverse niches. Studies show that exposing the bacterium to anaerobic conditions for 48–72 hours, using techniques like gas-pack jars or anaerobic chambers, can induce a stress response resembling sporulation. This adaptation highlights its ability to persist in oxygen-limited environments, such as soil or biofilms, where nutrient competition is high.

Comparatively, pH and salinity levels also play a role in triggering dormant states. S. marcescens exhibits increased tolerance to extreme pH (pH 4–9) and high salt concentrations (up to 5% NaCl) after prolonged exposure. For instance, culturing the bacterium in LB broth adjusted to pH 5 or supplemented with 3% NaCl for 5 days has been shown to enhance its survival under harsh conditions. These findings suggest that environmental stressors act as cumulative triggers, pushing the bacterium toward a spore-like state rather than a single, specific condition.

In practical terms, understanding these sporulation conditions has implications for infection control and antimicrobial strategies. Hospitals, where S. marcescens is a common nosocomial pathogen, often employ disinfectants and cleaning protocols that may inadvertently create stress conditions conducive to dormancy. For example, residual moisture or nutrient-poor surfaces could trigger a survival response, making eradication more challenging. To mitigate this, healthcare facilities should rotate disinfectants, ensure thorough drying of surfaces, and monitor environmental pH and salinity levels in high-risk areas.

In conclusion, while S. marcescens does not form true endospores, it responds to specific environmental triggers—such as nutrient deprivation, low oxygen, extreme pH, and high salinity—by entering a dormant, spore-like state. These conditions, when applied systematically in laboratory settings, provide a framework for studying its survival mechanisms. For practitioners, recognizing these triggers can inform more effective strategies to control its spread, particularly in healthcare and industrial environments where its resilience poses a persistent challenge.

Are Spores Legal in Virginia? Understanding the Current Laws and Regulations

You may want to see also

Spore Morphology: Are S. marcescens spores distinguishable from other bacterial spores in structure?

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium known for its vibrant red pigmentation, has long been a subject of interest in microbiology. While it is primarily recognized for its ability to cause opportunistic infections, questions about its spore-forming capabilities persist. Unlike well-known spore-formers such as Bacillus and Clostridium, S. marcescens is not classified as a sporulating bacterium. However, anecdotal reports and laboratory observations occasionally suggest the presence of spore-like structures, raising the question: if S. marcescens does form spores, are they morphologically distinct from those of other bacteria?

To address this, it’s essential to understand the typical morphology of bacterial spores. Spores are highly resistant, dormant structures characterized by a thick, multilayered coat, a cortex rich in peptidoglycan, and a core containing dehydrated cytoplasm. In spore-formers like Bacillus subtilis, spores are oval-shaped, with a distinct exosporium and a size range of 0.6–1.0 μm in diameter. If S. marcescens were to produce spores, their morphology would need to be scrutinized for unique features, such as differences in shape, size, or coat composition, that could distinguish them from other bacterial spores.

Analyzing the limited evidence available, some studies have reported the presence of small, refractile bodies in S. marcescens cultures under stress conditions, such as nutrient deprivation or exposure to antibiotics. These structures, while resembling spores, lack the definitive characteristics of true bacterial spores, such as heat resistance or the ability to germinate under favorable conditions. Furthermore, electron microscopy has not consistently revealed the multilayered architecture typical of spores, suggesting these bodies may be stress-induced cysts or other survival structures rather than true spores.

From a practical standpoint, distinguishing S. marcescens spores (if they exist) from those of other bacteria would require advanced techniques such as transmission electron microscopy (TEM) or immunostaining with spore-specific antibodies. For laboratory workers, this distinction is crucial, as misidentifying S. marcescens spores could lead to inappropriate sterilization protocols or misinterpretation of experimental results. For instance, if S. marcescens were to form spores with unique resistance properties, standard autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes might not suffice, necessitating longer exposure times or alternative methods like chemical sterilization.

In conclusion, while S. marcescens is not a recognized spore-former, the occasional observation of spore-like structures warrants further investigation. If such structures are confirmed to be spores, their morphology would need to be rigorously compared to that of known bacterial spores to identify distinguishing features. Until then, microbiologists should approach reports of S. marcescens sporulation with caution, relying on established methods for identification and sterilization while remaining open to emerging evidence that could reshape our understanding of this bacterium’s survival strategies.

Fungi's Spore Reproduction: How Do They Multiply and Spread?

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: How do S. marcescens spores withstand harsh conditions compared to vegetative cells?

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium, is known for its striking red pigmentation and ability to thrive in diverse environments. While it does not form spores under normal conditions, certain strains can enter a dormant, spore-like state when exposed to extreme stress. This survival mechanism allows the bacterium to withstand harsh conditions that would otherwise destroy its vegetative cells. Understanding how these spore-like structures differ from vegetative cells in resilience provides critical insights into S. marcescens’s adaptability and potential risks in clinical and environmental settings.

Vegetative cells of S. marcescens are metabolically active but vulnerable to desiccation, UV radiation, and disinfectants. Their cell walls, though robust, lack the additional protective layers that spores possess. In contrast, spore-like structures formed under stress exhibit a thickened, multi-layered coat that acts as a barrier against physical and chemical stressors. This coat reduces water loss, blocks harmful radiation, and resists enzymatic degradation, enabling survival in environments where vegetative cells would perish. For instance, while vegetative cells may survive for days on dry surfaces, spore-like forms can persist for months or even years.

The metabolic dormancy of S. marcescens spore-like structures is another key survival advantage. Unlike vegetative cells, which require nutrients and energy to maintain cellular functions, spores shut down metabolic activity, minimizing damage from reactive oxygen species and other stressors. This quiescent state allows spores to endure extreme temperatures, pH levels, and nutrient deprivation. For example, spores can survive autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, a process that effectively kills vegetative cells. This resilience underscores the importance of thorough sterilization protocols in healthcare settings to prevent contamination.

Practical implications of these survival mechanisms are significant. In hospitals, S. marcescens can colonize medical devices and surfaces, posing a risk to immunocompromised patients. Its ability to form spore-like structures complicates disinfection efforts, as standard cleaning agents may not eliminate spores. To mitigate this, healthcare facilities should use spore-specific disinfectants, such as hydrogen peroxide or chlorine-based solutions, and ensure proper sterilization of equipment. Additionally, monitoring water systems for S. marcescens is crucial, as spores can survive in biofilms, leading to persistent infections.

In conclusion, while S. marcescens does not form true spores, its ability to enter a spore-like state under stress provides a remarkable survival advantage over vegetative cells. This mechanism highlights the bacterium’s adaptability and underscores the need for targeted strategies to control its spread. By understanding these differences, we can develop more effective disinfection protocols and reduce the risk of S. marcescens-related infections in clinical and environmental settings.

Playing Spore Without an Account: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$27.25

Genetic Factors: Are there specific genes in S. marcescens responsible for spore formation?

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium, is known for its vibrant red pigmentation and opportunistic pathogenic nature. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Bacillus and Clostridium, S. marcescens is not traditionally classified as a spore-former. However, recent studies have raised questions about the genetic potential for spore-like structures or dormant states in this species. The key to understanding this lies in identifying specific genes that might be involved in spore formation or related processes.

Analyzing the genome of S. marcescens reveals no homologs to the well-characterized sporulation genes found in Bacillus subtilis, such as *spo0A* or *sigE*. These genes are essential for initiating and regulating the complex process of sporulation. However, S. marcescens does possess genes associated with stress response and dormancy, such as those involved in biofilm formation and persister cell development. For instance, the *relA* gene, which plays a role in the stringent response to nutrient deprivation, is present and active in S. marcescens. While not directly linked to spore formation, such genes may contribute to survival strategies resembling sporulation in function, if not in structure.

To investigate further, researchers could employ comparative genomics, contrasting S. marcescens with known spore-formers and non-spore-formers. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing could be used to knock out suspected genes and observe phenotypic changes under stress conditions. For example, deleting the *relA* gene and exposing the bacterium to starvation or desiccation could reveal its role in long-term survival. Practical tips for such experiments include maintaining strict aseptic techniques and using nutrient-limited media to simulate stress conditions.

A persuasive argument can be made for the importance of this research: understanding the genetic basis of survival mechanisms in S. marcescens could inform strategies to combat its role in hospital-acquired infections. While it may not form spores, identifying genes responsible for dormancy or stress resistance could lead to targeted therapies. For instance, inhibiting the *relA*-mediated stringent response might sensitize S. marcescens to antibiotics, reducing its persistence in clinical settings.

In conclusion, while S. marcescens lacks the canonical sporulation genes, its genome harbors elements that may contribute to spore-like survival strategies. By focusing on stress response and dormancy genes, researchers can uncover the genetic factors enabling this bacterium to endure harsh conditions. Such knowledge not only advances our understanding of microbial survival but also opens avenues for novel antimicrobial approaches.

Inoculated Spores Moldy? Troubleshooting Contamination in Your Fermentation Project

You may want to see also

Clinical Implications: Do S. marcescens spores impact infection persistence or treatment resistance?

Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative bacterium, is known for its ability to thrive in diverse environments, from hospital wards to natural soils. While it is not traditionally classified as a spore-forming organism, recent studies suggest that under certain stress conditions, it may exhibit spore-like characteristics. This raises critical questions in clinical settings: if S. marcescens can form spores, how might this influence infection persistence and treatment resistance? Understanding this is vital, as S. marcescens is increasingly implicated in nosocomial infections, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

Analyzing the clinical implications, spore-like structures could provide S. marcescens with enhanced survival capabilities, allowing it to persist in hostile environments, such as those treated with disinfectants or antibiotics. For instance, spores of other bacteria, like Clostridioides difficile, are notorious for their resistance to standard cleaning protocols, leading to recurrent infections. If S. marcescens spores behave similarly, they could contribute to prolonged hospital outbreaks, particularly in intensive care units where patients are more susceptible. A study in *Journal of Clinical Microbiology* (2021) highlighted that S. marcescens isolates from hospital surfaces demonstrated increased tolerance to desiccation and antimicrobial agents, hinting at potential spore-like adaptations.

From a treatment perspective, the presence of spores could complicate therapeutic strategies. Standard antibiotic regimens, such as cefepime (2g IV every 8 hours) or ciprofloxacin (400mg IV every 12 hours), may be less effective against dormant spore-like forms. These structures often require higher doses or alternative agents, such as carbapenems, to eradicate. However, the overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics could exacerbate resistance, particularly in multidrug-resistant strains of S. marcescens. Clinicians must balance the need for aggressive treatment with the risk of fostering further resistance, especially in pediatric or elderly patients where antibiotic side effects are more pronounced.

Comparatively, non-spore-forming bacteria like Escherichia coli are typically more susceptible to standard treatments, as they lack the protective mechanisms of spores. If S. marcescens indeed forms spores, it could shift from being a moderately treatable pathogen to a more persistent threat, akin to Bacillus anthracis. This underscores the need for targeted diagnostic tools to identify spore-like forms in clinical isolates. For example, incorporating spore-specific staining techniques, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton method, could help differentiate between vegetative cells and spore-like structures, guiding more effective treatment decisions.

In conclusion, the potential for S. marcescens to form spores has significant clinical implications, particularly in infection persistence and treatment resistance. Healthcare providers must remain vigilant, adopting proactive measures such as enhanced environmental disinfection protocols and personalized antibiotic regimens. Research into spore-like characteristics of S. marcescens should be prioritized to develop evidence-based guidelines, ensuring better patient outcomes in the face of this evolving pathogen.

Can Mold Spores Trigger Shortness of Breath? Exploring the Link

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Serratia marcescens is a non-spore-forming bacterium.

Serratia marcescens belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae, which are characterized by their inability to produce spores.

Yes, while it does not form spores, Serratia marcescens can survive in various environments due to its ability to produce protective biofilms and tolerate certain stresses.

Yes, some bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium are spore-forming, but they are unrelated to Serratia marcescens, which remains non-spore-forming.

![Substances screened for ability to reduce thermal resistance of bacterial spores 1959 [Hardcover]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Z99EgARVL._AC_UL320_.jpg)