Fungi are a diverse group of organisms that play crucial roles in ecosystems, from decomposing organic matter to forming symbiotic relationships with plants. One of the most fascinating aspects of fungi is their reproductive strategies, which often involve the production of spores. Spores are microscopic, lightweight structures that allow fungi to disperse widely and survive in harsh conditions. Unlike plants and animals, fungi do not rely on seeds or offspring for reproduction; instead, they release spores into the environment, which can germinate under favorable conditions to form new fungal individuals. This method of reproduction is highly efficient and enables fungi to colonize diverse habitats, making spores a fundamental feature of their life cycle. Understanding how fungi reproduce by spores not only sheds light on their biology but also highlights their ecological significance and adaptability.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Fungi primarily reproduce through spores. |

| Types of Spores | Asexual (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) and sexual (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores). |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Wind, water, insects, animals, and human activities. |

| Survival Capabilities | Spores are highly resistant to harsh conditions (e.g., heat, cold, desiccation). |

| Germination | Spores germinate under favorable conditions (e.g., moisture, nutrients). |

| Role in Life Cycle | Essential for propagation, dispersal, and survival of fungal species. |

| Diversity | Fungi produce spores in various structures (e.g., sporangia, asci, basidia). |

| Ecological Importance | Key role in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and ecosystem balance. |

| Human Impact | Spores can cause allergies, diseases, and food spoilage but are also used in biotechnology (e.g., antibiotics, fermentation). |

| Ubiquity | Fungi and their spores are found in almost every environment on Earth. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Types of fungal spores

Fungi are masters of survival, and their reproductive strategies reflect this. One of their most remarkable adaptations is the production of spores, microscopic units designed for dispersal and dormancy. These spores are not one-size-fits-all; they come in a variety of types, each tailored to specific environmental conditions and reproductive needs. Understanding these types sheds light on the diversity and resilience of fungal life.

Sporangiospores are a prime example of fungal ingenuity. Produced within a structure called a sporangium, these spores are common in zygomycetes, a group of fungi often found in soil and decaying matter. When conditions are right, the sporangium bursts open, releasing thousands of spores into the air. This explosive dispersal mechanism ensures that even a small fungus can colonize vast areas. For instance, *Rhizopus stolonifer*, the mold responsible for black bread mold, relies on sporangiospores to spread rapidly across damp, sugary surfaces. To prevent such fungi from taking over your kitchen, maintain low humidity and promptly refrigerate perishable foods.

In contrast, conidia are asexual spores produced at the ends of specialized hyphae called conidiophores. These spores are characteristic of ascomycetes and deuteromycetes, groups that include common molds like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*. Conidia are highly resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions such as drought or extreme temperatures. Their production is often triggered by environmental stress, making them a key survival tool. For example, *Aspergillus niger*, a fungus used in food production, releases conidia that can remain dormant for years before germinating under favorable conditions. If you’re cultivating fungi for industrial purposes, controlling light and nutrient levels can optimize conidia production.

Zygospores represent a different reproductive strategy, one focused on long-term survival rather than rapid dispersal. Formed through the fusion of two compatible hyphae, zygospores are thick-walled and highly resistant to environmental extremes. This type of spore is typical in zygomycetes and is often found in soil. Zygospores can remain dormant for decades, waiting for the right conditions to germinate. For gardeners, this means that fungal spores in the soil can persist through multiple seasons, ready to emerge when moisture and temperature align. To manage soil fungi, rotate crops and avoid overwatering to disrupt their life cycle.

Finally, basidiospores are the hallmark of basidiomycetes, a group that includes mushrooms, puffballs, and rusts. These spores are produced on club-shaped structures called basidia and are released into the air in a manner similar to pollen. Basidiospores are lightweight and can travel long distances, making them effective colonizers of new habitats. For instance, the spores of *Agaricus bisporus*, the common button mushroom, are dispersed by wind and can germinate in nutrient-rich soil. If you’re cultivating mushrooms, ensure proper ventilation to facilitate spore dispersal and colonization.

Each type of fungal spore is a testament to the adaptability of fungi. From the explosive release of sporangiospores to the resilience of zygospores, these structures enable fungi to thrive in virtually every ecosystem on Earth. By understanding their unique characteristics, we can better manage fungal growth in agriculture, industry, and even our homes. Whether you’re a gardener, a food scientist, or simply curious about the natural world, recognizing the diversity of fungal spores offers valuable insights into the hidden kingdom of fungi.

Bacillus Cereus Spores: Heat Sensitivity and Food Safety Concerns

You may want to see also

Sporulation process in fungi

Fungi are masters of survival, and their ability to reproduce through spores is a key strategy. The sporulation process is a complex, highly regulated sequence that ensures the fungus’s genetic continuity in diverse environments. Unlike simple cell division, sporulation involves the formation of specialized structures designed to withstand harsh conditions, disperse widely, and germinate when conditions are favorable. This process is not just a means of reproduction but a testament to fungi’s adaptability and resilience.

Consider the steps involved in sporulation, which vary across fungal species but share common principles. In *Aspergillus*, for example, the process begins with the formation of a structure called a vesicle, which develops into a sterigma. From this, conidia (asexual spores) are produced in chains, ready for dispersal. In contrast, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast) undergoes sporulation under nutrient-limited conditions, forming four haploid spores within a protective ascus. Each step is tightly controlled by environmental cues, such as nutrient availability, pH, and temperature, ensuring sporulation occurs only when necessary.

One of the most fascinating aspects of sporulation is its efficiency in dispersal. Fungal spores are lightweight and often equipped with structures like wings or hydrophobic surfaces, allowing them to travel via air, water, or animal vectors. For instance, the spores of *Penicillium* are carried by air currents, enabling them to colonize new substrates rapidly. This dispersal mechanism is critical for fungi, which lack mobility in their vegetative state. Practical tip: To prevent fungal contamination in food storage, maintain low humidity (below 60%) and temperatures below 4°C, as these conditions inhibit spore germination.

Comparatively, sporulation in fungi is akin to seed production in plants, but with a key difference: fungal spores are more resilient. While plant seeds require specific conditions to germinate, fungal spores can remain dormant for years, surviving extreme temperatures, desiccation, and even radiation. This durability is achieved through the accumulation of protective compounds like melanin and trehalose during spore maturation. For researchers or hobbyists culturing fungi, understanding this resilience is crucial—sterilizing equipment at 121°C for 15–20 minutes ensures spore inactivation.

In conclusion, the sporulation process in fungi is a marvel of biological engineering, combining precision, adaptability, and efficiency. By studying this process, we gain insights into fungal ecology, disease control, and biotechnological applications. Whether you’re a gardener battling powdery mildew or a scientist developing antifungal drugs, understanding sporulation is essential. Practical takeaway: Regularly inspect plants for early signs of fungal growth, such as white powdery patches, and apply fungicides preventively during humid seasons to disrupt the sporulation cycle.

Exploring the Mystery: Are Gas Giants New to Spore's Universe?

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for spore release

Fungi are masters of adaptation, and their reproductive strategies reflect this. One of the most fascinating aspects of fungal reproduction is the release of spores, a process heavily influenced by environmental cues. These triggers act as signals, prompting fungi to disperse their genetic material and ensure survival in diverse ecosystems. Understanding these environmental factors is crucial for fields like agriculture, medicine, and ecology, where fungal growth and spread can have significant impacts.

Light and Darkness: The Photoperiodic Dance

Light plays a pivotal role in regulating spore release in many fungal species. Some fungi, like certain molds, are photophobic, releasing spores in darkness. This adaptation allows them to avoid desiccation and UV damage during the day. Conversely, other fungi, such as some mushroom species, are photophilic, using light as a cue to initiate spore discharge. This photoperiodic sensitivity ensures spores are released when conditions are optimal for dispersal and germination.

Humidity: The Moisture Trigger

Moisture is another critical environmental factor. High humidity levels often signal favorable conditions for spore germination and subsequent fungal growth. Many fungi have evolved to release spores when humidity reaches a certain threshold, increasing the chances of successful colonization. This is particularly evident in damp environments like forests and decaying organic matter, where fungi thrive.

Nutrient Availability: Fueling Reproduction

The presence of specific nutrients can also act as a trigger for spore release. Some fungi are highly sensitive to nutrient availability, particularly carbohydrates and nitrogen sources. When these nutrients are abundant, fungi may accelerate spore production and release, capitalizing on the favorable conditions for growth and reproduction. This strategy ensures that spores are dispersed when resources are plentiful, increasing the likelihood of successful establishment in new environments.

Temperature Fluctuations: A Thermal Cue

Temperature changes can serve as a subtle yet effective trigger for spore release. Some fungi are adapted to release spores in response to specific temperature ranges. For instance, certain species may initiate spore discharge when temperatures drop, a mechanism that could be linked to seasonal changes and the preparation for winter dormancy. Others might respond to temperature increases, signaling the arrival of warmer seasons conducive to growth.

Mechanical Stimuli: The Power of Touch

Interestingly, physical contact can also induce spore release in some fungi. This mechanism, known as touch-induced sporulation, is observed in various species. When disturbed by rain, wind, or even passing animals, these fungi release spores, ensuring dispersal over a wider area. This adaptation highlights the versatility of fungal reproductive strategies and their ability to exploit various environmental cues for survival and propagation.

In summary, the release of spores in fungi is a complex process orchestrated by a symphony of environmental triggers. From light and humidity to nutrients and temperature, these factors collectively influence the timing and intensity of spore discharge. Understanding these triggers is essential for managing fungal populations, whether in agricultural settings, natural ecosystems, or medical contexts, where controlling fungal growth and spread is crucial. By deciphering these environmental cues, we gain valuable insights into the intricate world of fungal reproduction and its impact on our surroundings.

Can Spores or Pollen Survive in Distilled Water? Exploring the Science

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of spores in fungal survival

Fungi, unlike animals and plants, lack the ability to move freely in search of favorable conditions. Instead, they rely on spores—microscopic, lightweight structures—to disperse and colonize new environments. These spores are not just reproductive units; they are survival capsules, equipped to endure harsh conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, and nutrient scarcity. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores can survive for years in soil, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. This resilience ensures fungal persistence across generations, even in unpredictable ecosystems.

Consider the lifecycle of a fungus: when resources deplete or conditions deteriorate, it produces spores through asexual (e.g., conidia) or sexual (e.g., asci, basidiospores) means. These spores are aerodynamically designed for wind dispersal, traveling miles before settling in new habitats. Once landed, they remain dormant until environmental cues—like moisture or warmth—trigger germination. This adaptive strategy allows fungi to thrive in diverse biomes, from arid deserts to dense forests. For gardeners, understanding this mechanism can inform practices like crop rotation to disrupt fungal spore cycles.

From an evolutionary standpoint, spores are fungi’s answer to environmental unpredictability. Unlike seeds in plants, which require immediate germination, fungal spores can remain viable for decades. This longevity is critical for species survival during catastrophic events, such as wildfires or climate shifts. For example, *Neurospora* spores have been revived from 20-million-year-old amber, showcasing their durability. Such traits make fungi key players in ecosystem recovery, as they decompose organic matter and recycle nutrients post-disturbance.

Practical applications of spore survival mechanisms are vast. In agriculture, fungicides target spore germination to control pathogens like *Botrytis cinerea*, which causes gray mold in crops. However, overuse can lead to resistance, emphasizing the need for integrated pest management. Homeowners can reduce fungal infestations by minimizing spore dispersal—keeping humidity low, ventilating damp areas, and promptly removing decaying organic material. Understanding spore behavior also aids in mycoremediation, where fungi are used to degrade pollutants, leveraging their ability to colonize contaminated sites via spores.

In conclusion, spores are not merely reproductive tools but lifeboats for fungal survival. Their ability to withstand adversity, disperse widely, and remain dormant ensures fungal persistence in dynamic environments. Whether in natural ecosystems or human-managed spaces, recognizing the role of spores empowers us to coexist with fungi—either by harnessing their benefits or mitigating their harms. This knowledge bridges the gap between scientific curiosity and practical application, offering insights into both fungal biology and its real-world implications.

Unveiling the Spore-Producing Structures: A Comprehensive Guide to Identification

You may want to see also

Methods of spore dispersal in fungi

Fungi have evolved diverse strategies to disperse their spores, ensuring survival and propagation across varied environments. One of the most common methods is wind dispersal, where lightweight spores are released into the air and carried over long distances. For instance, the ascomycetes and basidiomycetes produce spores that are aerodynamically designed to float effortlessly, sometimes traveling miles before settling on a new substrate. This method is particularly effective in open environments like forests and grasslands, where air currents are abundant.

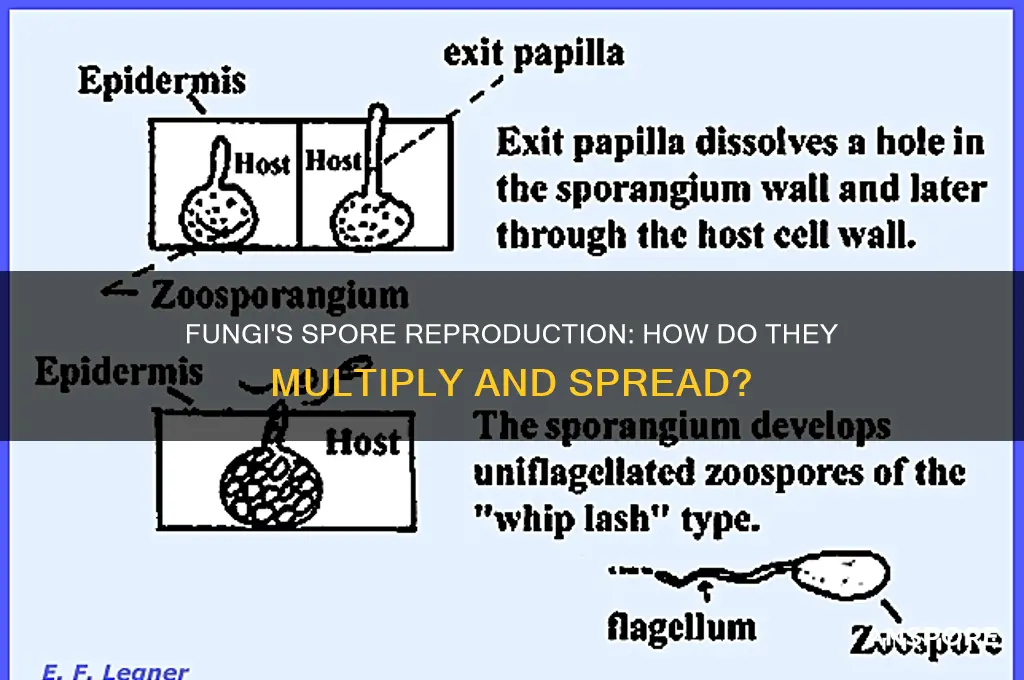

Another ingenious method is water dispersal, employed by fungi in aquatic or damp habitats. Spores of certain species, such as those in the phylum Chytridiomycota, are released into water bodies, where they can be carried by currents to new locations. This strategy is especially useful in stagnant or slow-moving waters, where spores can adhere to surfaces or be ingested by organisms, facilitating colonization. For gardeners or hobbyists cultivating water-loving fungi, ensuring a gentle water flow can enhance spore distribution without causing damage.

Animal-mediated dispersal is a third method, where spores hitch a ride on the bodies of insects, birds, or other animals. Fungi like the oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) produce sticky spores that adhere to insect exoskeletons, while others, such as bird’s nest fungi (*Cyathus* spp.), have cup-like structures that eject spores when raindrops hit them, mimicking a splash cup. To encourage this in a controlled setting, placing fungi near insect pathways or in areas frequented by wildlife can increase dispersal rates.

Finally, active ejection mechanisms showcase fungi’s ability to propel spores with force. The cannonball fungus (*Sphaerobolus stellatus*) uses a pressurized fluid sac to launch spores several meters away, while puffballs (*Lycoperdon* spp.) release clouds of spores when disturbed. These methods are highly efficient in localized environments, ensuring spores land in nearby suitable habitats. For enthusiasts studying these fungi, observing them during humid conditions or after rainfall can provide optimal viewing of these mechanisms in action.

Understanding these dispersal methods not only highlights fungi’s adaptability but also offers practical insights for cultivation, conservation, and disease management. Whether in a laboratory, garden, or natural setting, recognizing how spores travel can enhance efforts to propagate beneficial fungi or control harmful species.

The Last of Us: Unveiling the Truth About Spores in the Show

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, all fungi can reproduce by spores, though some may also use other methods like fragmentation or vegetative reproduction.

Fungi produce spores through specialized structures like sporangia, basidia, or asci, depending on the fungal group.

Fungal spores can be either sexual (formed after meiosis) or asexual (formed through mitosis), depending on the reproductive process.

Fungal spores disperse through air, water, animals, or other environmental factors, allowing fungi to spread to new habitats.

Yes, many fungal spores are highly resilient and can survive extreme temperatures, dryness, and other harsh environmental conditions for extended periods.