The sporophyte is a crucial stage in the life cycle of plants, particularly in vascular plants like ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. It is the diploid phase that follows fertilization, where the sporophyte plant produces spores through a process called sporogenesis. These spores are haploid cells that develop into the gametophyte generation, which in turn produces gametes for sexual reproduction. While the sporophyte is known for its dominant and long-lived form in many plant groups, its primary function is indeed to generate spores, ensuring the continuation of the plant's life cycle. This raises the question: does the sporophyte produce spores, and if so, how does this process contribute to the plant's reproductive success?

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does Sporophyte Produce Spores? | Yes |

| Type of Spores Produced | Diploid (2n) spores |

| Process of Spore Production | Meiosis in sporangia |

| Location of Sporangia | On the sporophyte plant (e.g., leaves, stems, or specialized structures like cones or capsules) |

| Function of Spores | Dispersal and development into gametophyte generation |

| Life Cycle Stage | Part of the alternation of generations in plants |

| Examples of Sporophytes | Ferns, mosses, gymnosperms (e.g., pines), and angiosperms (flowering plants) |

| Contrast with Gametophyte | Gametophyte produces gametes (sperm and eggs), while sporophyte produces spores |

| Dominant Generation | In vascular plants (ferns, gymnosperms, angiosperms), the sporophyte is the dominant generation |

| Genetic Composition | Diploid (2n), formed from the fusion of two haploid gametes |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporophyte Life Cycle: Role in alternation of generations, producing spores for gametophyte development

- Spore Formation: Meiosis in sporophyte creates haploid spores for dispersal

- Types of Spores: Differentiation into microspores (male) and megaspores (female)

- Sporangia Function: Structures where sporophyte produces and stores spores

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like light, moisture, and temperature influence spore release

Sporophyte Life Cycle: Role in alternation of generations, producing spores for gametophyte development

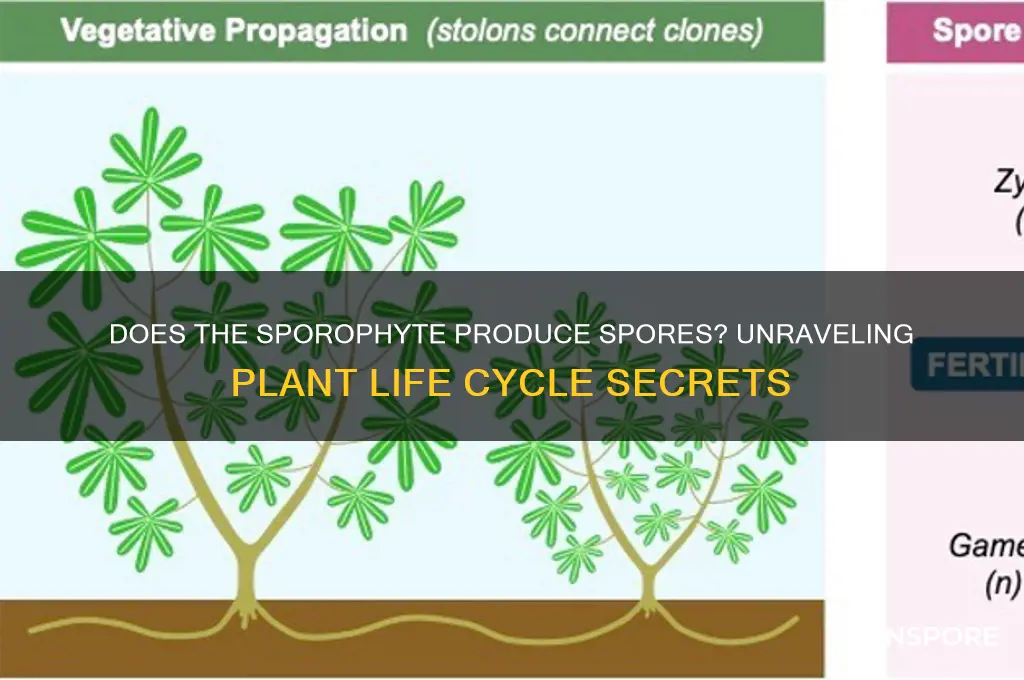

The sporophyte phase is a cornerstone of the alternation of generations, a life cycle exhibited by plants, algae, and certain fungi. This phase is characterized by the production of spores, which are essential for the development of the gametophyte generation. In vascular plants, such as ferns and seed plants, the sporophyte is the dominant, long-lived stage, while the gametophyte is typically smaller and shorter-lived. The sporophyte's primary role is to ensure the continuation of the species by generating spores through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid cells.

Consider the life cycle of a fern as an illustrative example. The sporophyte fern plant produces spore cases, or sporangia, on the undersides of its fronds. Within these sporangia, spores are formed via meiosis. When released, these spores germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes, known as prothalli. The prothallus is a critical but often overlooked stage, as it produces both sperm and eggs. Fertilization occurs when sperm from one prothallus swims to the egg of another, typically aided by water. This union results in a diploid zygote, which develops into a new sporophyte, thus completing the cycle.

From an analytical perspective, the sporophyte's spore production is a highly efficient mechanism for genetic diversity. Meiosis introduces variation through crossing over and independent assortment, ensuring that each spore is genetically unique. This diversity is crucial for the survival of plant species, as it allows populations to adapt to changing environments. For instance, in a forest ecosystem, ferns with varied spore genetics may have differing resistances to pests or diseases, increasing the overall resilience of the fern population.

For those interested in cultivating plants that exhibit alternation of generations, understanding the sporophyte's role is key. In horticulture, propagating ferns from spores requires specific conditions: a humid environment, indirect light, and a sterile medium. Spores should be sown thinly on the surface of the medium and kept consistently moist. Germination can take several weeks, and the resulting prothalli are delicate, requiring careful maintenance. Once the sporophyte begins to develop, it can be transplanted into a more typical growing environment.

In conclusion, the sporophyte's production of spores is not merely a biological process but a strategic evolutionary adaptation. By generating genetically diverse spores, the sporophyte ensures the longevity and adaptability of its species. Whether observed in the wild or cultivated in a garden, this phase of the life cycle highlights the intricate balance between stability and variation in the natural world. Understanding and appreciating this process enriches both scientific knowledge and practical skills in plant propagation.

Using Grub Control with Milky Spore: Compatibility and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Spore Formation: Meiosis in sporophyte creates haploid spores for dispersal

In the life cycle of plants, the sporophyte generation plays a pivotal role in spore formation, a process essential for the continuation of species. The sporophyte, a diploid phase, undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores, which are then dispersed to grow into the gametophyte generation. This mechanism ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, crucial for survival in varying environments. For instance, ferns and mosses rely heavily on this process, with spores being lightweight and easily carried by wind or water, allowing them to colonize new areas efficiently.

To understand spore formation, consider the steps involved in meiosis within the sporophyte. Meiosis is a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid cells. In plants, this occurs in specialized structures like sporangia. For example, in angiosperms, meiosis takes place in the anthers (male) and ovules (female) to produce pollen grains and embryo sacs, respectively. These haploid spores are then dispersed, either through biotic means (like insects) or abiotic means (like wind), to reach suitable habitats for growth. Practical tip: Observing fern sori under a magnifying glass can reveal the intricate arrangement of sporangia where meiosis occurs, offering a tangible connection to this process.

From a comparative perspective, spore formation in sporophytes differs significantly from seed production in higher plants. While seeds contain a fully developed embryo and stored nutrients, spores are essentially single cells that must develop into gametophytes before reproduction can occur. This distinction highlights the evolutionary advantage of seeds in more complex plants, providing greater protection and resources for the developing embryo. However, spores remain the primary dispersal unit in lower plants like bryophytes and pteridophytes, showcasing the efficiency of this ancient reproductive strategy.

Persuasively, the study of spore formation through meiosis in sporophytes underscores the elegance of plant reproductive systems. By producing haploid spores, plants maximize genetic recombination, increasing the likelihood of offspring adapting to changing conditions. For educators and enthusiasts, demonstrating this process through hands-on activities, such as growing ferns from spores or dissecting sporangia, can deepen appreciation for the complexity of plant life cycles. Caution: When handling spores, ensure proper ventilation, as their small size can pose respiratory risks if inhaled in large quantities.

In conclusion, spore formation via meiosis in the sporophyte is a fundamental process that drives plant diversity and dispersal. By creating haploid spores, plants ensure genetic variability and the ability to colonize new environments. Whether in a classroom, laboratory, or natural setting, exploring this process provides valuable insights into the resilience and adaptability of plant life. Practical takeaway: For those interested in horticulture or botany, understanding spore formation can enhance techniques in plant propagation and conservation efforts, particularly for endangered species reliant on spore dispersal.

Can You Extract Psilocybin Spores from Your Mushrooms? A Guide

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Differentiation into microspores (male) and megaspores (female)

Sporophytes, the diploid phase in the life cycles of plants and certain algae, indeed produce spores as a fundamental part of their reproductive strategy. Among these spores, a critical differentiation occurs: microspores and megaspores. Microspores develop into male gametophytes, while megaspores develop into female gametophytes. This division is essential for sexual reproduction in heterosporous plants, such as seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms), ensuring genetic diversity and species survival.

Analytical Perspective:

The production of microspores and megaspores is a highly regulated process, driven by hormonal and environmental cues. In angiosperms, for instance, microsporogenesis occurs within the anthers, where microspores give rise to pollen grains. Megasporogenesis, on the other hand, takes place in the ovule, where one of the four megaspores typically survives to form the female gametophyte. This asymmetry in development highlights the efficiency of resource allocation, as the female gametophyte requires more energy to support the eventual embryo. Understanding this differentiation is crucial for plant breeding and agricultural advancements, as it directly impacts seed production and crop yield.

Instructive Approach:

To observe this process, botanists often use staining techniques and microscopy. For example, acetocarmine staining can highlight the nuclei of spores during meiosis, making it easier to distinguish microspores from megaspores. In gymnosperms like pine trees, microspores are produced in pollen cones, while megaspores develop in ovulate cones. Educators can demonstrate this by dissecting cones and examining their sporophylls under a stereoscope. For students, this hands-on approach reinforces the concept of spore differentiation and its role in plant reproduction.

Comparative Analysis:

While heterosporous plants produce both microspores and megaspores, homosporous plants (e.g., ferns and mosses) produce only one type of spore. This distinction underscores the evolutionary advantage of heterospory, which allows for more specialized reproductive structures and greater adaptability to diverse environments. For instance, the larger size of megaspores provides ample resources for the developing female gametophyte, a trait particularly beneficial in arid or nutrient-poor conditions. In contrast, the smaller, more numerous microspores facilitate efficient pollen dispersal, increasing the likelihood of fertilization.

Descriptive Insight:

Imagine a pine forest in spring, where pollen cones release clouds of microspores, carried by the wind to reach ovulate cones. Within these ovulate cones, megaspores undergo meiosis, and one develops into a multicellular female gametophyte. This vivid example illustrates the ecological significance of spore differentiation, as it ensures the continuation of plant species across generations. The interplay between microspores and megaspores is not just a biological process but a cornerstone of forest ecosystems, influencing everything from soil health to wildlife habitats.

Practical Takeaway:

For gardeners and farmers, understanding spore differentiation can optimize plant care. For example, ensuring adequate moisture and temperature during the sporophyte phase can enhance spore production in crops like corn or wheat. Additionally, recognizing the signs of successful pollination—such as the development of seeds from fertilized megaspores—can guide decisions about irrigation and pest control. By appreciating the roles of microspores and megaspores, cultivators can foster healthier, more productive plants, ultimately contributing to food security and biodiversity.

Microban's Effectiveness Against C. Diff Spores: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sporangia Function: Structures where sporophyte produces and stores spores

Sporangia are the unsung heroes of the plant kingdom, serving as the factories where sporophytes produce and store spores. These specialized structures are critical for the life cycle of ferns, mosses, and other spore-producing plants, ensuring their survival and propagation. Within the sporangia, spores develop through a process called sporogenesis, which involves the division of cells to create haploid spores. These spores are then released into the environment, where they can germinate under favorable conditions, giving rise to the next generation of plants.

Consider the fern as a prime example. On the underside of its fronds, you’ll find clusters of sporangia called sori. Each sporangium is a tiny, capsule-like structure that houses hundreds of spores. When mature, the sporangium dries out, and its wall splits open, dispersing the spores to the wind. This mechanism is not just efficient but also adaptive, allowing ferns to colonize diverse habitats, from shady forests to rocky crevices. For gardeners cultivating ferns, understanding this process can optimize spore collection for propagation—simply place a sheet of paper under the sori and gently tap the frond to release the spores.

From an evolutionary standpoint, sporangia represent a remarkable adaptation to life on land. Unlike aquatic plants that rely on water to transport gametes, spore-producing plants use sporangia to create lightweight, durable spores that can travel vast distances. This innovation enabled plants to thrive in terrestrial environments, laying the foundation for the diversity of plant life we see today. For educators, illustrating this concept with a comparison between aquatic algae and land-dwelling ferns can highlight the significance of sporangia in plant evolution.

Practical applications of sporangia extend beyond biology classrooms. In agriculture, understanding sporangial function is crucial for managing plant diseases caused by spore-producing pathogens, such as rusts and mildews. For instance, farmers can reduce the spread of wheat rust by monitoring sporangial development and applying fungicides at critical stages. Similarly, in horticulture, knowing when sporangia are mature can aid in the controlled pollination of ferns or the prevention of unwanted spore dispersal in greenhouses.

In conclusion, sporangia are not merely storage units but dynamic structures that drive the reproductive success of sporophytes. Their role in spore production and dispersal underscores their importance in both natural ecosystems and human endeavors. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or educator, appreciating the function of sporangia offers valuable insights into the intricate mechanisms of plant life.

Are Mildew Spores Dangerous? Understanding Health Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: Factors like light, moisture, and temperature influence spore release

Sporophytes, the spore-producing phase in the life cycle of plants like ferns and mosses, don't release spores randomly. Environmental cues act as precise triggers, ensuring dispersal occurs under optimal conditions for germination and survival. Light, moisture, and temperature are the primary conductors of this intricate dance, each playing a distinct role in signaling the sporophyte to release its reproductive units.

Light, particularly its intensity and duration, acts as a crucial zeitgeber, synchronizing spore release with favorable conditions. Many fern species, for instance, exhibit peak spore discharge during early morning hours when light intensity is moderate. This timing coincides with cooler temperatures and higher humidity, creating a microclimate conducive to spore hydration and dispersal. Studies have shown that red and far-red light wavelengths can significantly influence spore release in certain species, highlighting the specificity of this light-mediated response.

Moisture, both in the air and on the sporophyte itself, is another critical factor. Dry conditions can inhibit spore release, as dehydration damages the delicate structures involved in dispersal. Conversely, high humidity often triggers the opening of sporangia, the spore-containing structures, allowing spores to be released and carried by air currents. For example, in some mosses, a thin film of water is necessary for the explosive discharge of spores, a mechanism that propels them over greater distances.

Understanding these environmental triggers has practical applications. Horticulturists can manipulate light exposure and humidity levels to control spore release in cultivated plants, ensuring successful propagation. Additionally, this knowledge aids in predicting and managing the spread of spore-borne pathogens, which often rely on specific environmental cues for dispersal.

Temperature acts as a fine-tuning mechanism, influencing the timing and rate of spore release. Generally, warmer temperatures accelerate the maturation of spores and increase the frequency of discharge. However, extreme heat can be detrimental, desiccating spores and hindering their viability. Certain plant species have evolved temperature-sensitive mechanisms to prevent spore release during unfavorable conditions. For instance, some ferns delay spore discharge until temperatures drop below a certain threshold, ensuring dispersal occurs during cooler, more humid periods.

By orchestrating spore release through these environmental triggers, sporophytes maximize the chances of their offspring's success. This intricate interplay between light, moisture, and temperature ensures that spores are dispersed when conditions are optimal for germination, growth, and establishment of the next generation. Recognizing these environmental cues not only deepens our understanding of plant reproduction but also empowers us to harness this knowledge for practical applications in horticulture, conservation, and disease management.

Can Rothia Mucilaginosa Form Spores? Exploring Its Reproductive Capabilities

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the sporophyte is the diploid phase in the life cycle of plants and algae that produces spores through meiosis.

The sporophyte produces haploid spores, which develop into the gametophyte generation in the plant life cycle.

In vascular plants like ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms, the sporophyte is the dominant and long-lived phase that produces spores.

![The Development of the Sporophyte of Sphaerocarpos Donnellii / by Eliza Margaret Ritchie 1900 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)