*Rothia mucilaginosa*, a Gram-positive bacterium commonly found in the human oral cavity and upper respiratory tract, is primarily known for its commensal role in the microbiome. However, its ability to form spores remains a topic of scientific inquiry. Unlike well-known spore-forming bacteria such as *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*, *Rothia mucilaginosa* has not been conclusively demonstrated to produce spores under standard laboratory conditions. Current research suggests that this bacterium relies on other mechanisms, such as biofilm formation and metabolic adaptability, to survive in diverse environments. While some studies have explored its resilience in harsh conditions, there is no definitive evidence to support spore formation in *R. mucilaginosa*. Further investigation is needed to fully understand its survival strategies and whether spore-like structures or alternative dormant states might exist.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Formation | No, Rothia mucilaginosa is not capable of forming spores. |

| Gram Staining | Gram-positive |

| Morphology | Cocci or coccobacilli, often seen in pairs or clusters (diplococci). |

| Cell Wall Composition | Contains peptidoglycan and teichoic acids. |

| Metabolism | Facultative anaerobe, capable of both aerobic and anaerobic growth. |

| Optimal Growth Temperature | 35-37°C (mesophilic). |

| Habitat | Normal flora of the human oral cavity and upper respiratory tract. |

| Pathogenicity | Opportunistic pathogen, rarely causes infections in immunocompromised individuals. |

| Antibiotic Susceptibility | Generally susceptible to penicillin, cephalosporins, and vancomycin. |

| Biochemical Tests | Positive for catalase, negative for oxidase. |

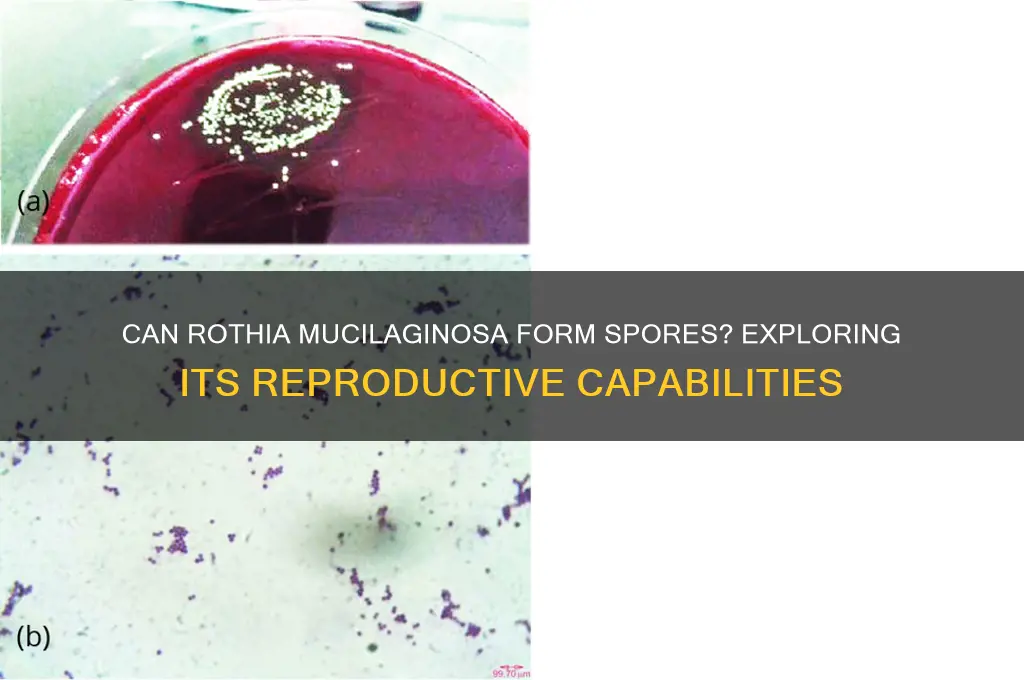

| Colony Characteristics | Small, convex, smooth, and cream-colored colonies on blood agar. |

| Genome | Non-spore-forming, consistent with its inability to produce spores. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Conditions: Optimal environmental factors triggering Rothia mucilaginosa spore formation

- Spore Morphology: Structural characteristics of Rothia mucilaginosa spores under microscopy

- Genetic Basis: Genes and pathways involved in Rothia mucilaginosa sporulation processes

- Survival Mechanisms: Role of spores in Rothia mucilaginosa's environmental persistence

- Clinical Relevance: Impact of Rothia mucilaginosa spore formation on human health and disease

Sporulation Conditions: Optimal environmental factors triggering Rothia mucilaginosa spore formation

Rothia mucilaginosa, a Gram-positive bacterium commonly found in the human oral cavity, has been a subject of interest in microbial research. While it is not traditionally known as a spore-forming bacterium, recent studies suggest that under specific environmental conditions, it may exhibit sporulation capabilities. Understanding the optimal factors that trigger spore formation in R. mucilaginosa is crucial for both clinical and industrial applications, as spores are highly resistant forms that can survive harsh conditions.

Environmental Triggers for Sporulation

Sporulation in R. mucilaginosa is influenced by nutrient deprivation, particularly the depletion of carbon and nitrogen sources. When grown in minimal media with limited glucose (e.g., concentrations below 0.1% w/v) and ammonium sulfate (below 0.05% w/v), the bacterium responds by initiating spore formation as a survival mechanism. Additionally, pH levels play a critical role; slightly alkaline conditions (pH 7.5–8.0) have been observed to enhance sporulation efficiency compared to neutral or acidic environments. Temperature is another key factor, with optimal sporulation occurring at 30–35°C, mirroring the bacterium’s natural habitat in the oral microbiome.

Oxygen and Osmotic Stress

While R. mucilaginosa is generally aerobic, sporulation is favored under microaerophilic conditions, where oxygen levels are reduced (approximately 5–10% O₂). This suggests that mild oxygen limitation acts as a stressor, prompting the bacterium to enter a dormant state. Osmotic stress, induced by high salt concentrations (e.g., 2–4% NaCl), further enhances sporulation by mimicking desiccation conditions. However, excessive salt levels (>5% NaCl) inhibit growth and sporulation, highlighting the need for precise environmental control.

Practical Applications and Considerations

For researchers aiming to induce sporulation in R. mucilaginosa, a stepwise approach is recommended. Begin by culturing the bacterium in rich medium (e.g., tryptic soy broth) for 24–48 hours, then transfer to sporulation medium (minimal salts, low glucose, and ammonium sulfate) for 5–7 days. Regularly monitor spore formation using phase-contrast microscopy or staining techniques like the Schaeffer-Fulton method. Caution should be exercised when handling spores, as their resistance to heat, chemicals, and radiation poses biosafety challenges, particularly in clinical settings.

Comparative Insights and Future Directions

Compared to well-studied spore-formers like Bacillus subtilis, R. mucilaginosa’s sporulation process is less efficient and more sensitive to environmental fluctuations. This underscores the need for further research to optimize conditions and understand the genetic mechanisms involved. Exploring the role of sporulation in R. mucilaginosa’s pathogenesis and its potential applications in biotechnology, such as probiotic formulations or biofilm control, could open new avenues for this understudied bacterium.

Mastering Spore Syringe Creation: A Step-by-Step DIY Guide

You may want to see also

Spore Morphology: Structural characteristics of Rothia mucilaginosa spores under microscopy

Rothia mucilaginosa, a Gram-positive bacterium commonly found in the human oral cavity, has been a subject of interest in microbiological studies. While it is primarily known for its role in oral health and occasional pathogenicity, the question of its spore-forming capability remains a point of investigation. Under microscopy, the structural characteristics of Rothia mucilaginosa spores reveal intriguing details that shed light on their morphology and potential functions.

Observation and Analysis:

When examined under a high-resolution microscope, Rothia mucilaginosa spores exhibit a distinct oval to spherical shape, typically measuring 0.5–1.0 μm in diameter. The spore wall is composed of multiple layers, including an outer exosporium, a thick peptidoglycan cortex, and an inner spore membrane. Notably, the exosporium appears as a thin, electron-dense layer that provides resistance to environmental stressors such as heat and desiccation. Unlike the highly refractile spores of Bacillus species, Rothia mucilaginosa spores display a smoother surface with minimal ornamentation, suggesting a less complex sporulation process.

Comparative Perspective:

In comparison to well-known spore-formers like Bacillus subtilis, Rothia mucilaginosa spores lack the pronounced proteinaceous coat layers and appendages that facilitate attachment and germination. This structural simplicity aligns with the bacterium's classification as a facultative anaerobe with limited environmental resilience. While Rothia mucilaginosa does not form spores as robust as those of obligate spore-formers, its sporulation process appears to be an adaptive mechanism for survival in the dynamic oral microbiome rather than a means of long-term persistence in harsh environments.

Practical Implications:

For microbiologists and clinicians, understanding the spore morphology of Rothia mucilaginosa is crucial for distinguishing it from other spore-forming bacteria in diagnostic settings. When identifying spores under microscopy, look for the characteristic smooth surface and uniform size, which differentiate Rothia mucilaginosa from more ornate spore structures. Additionally, this knowledge aids in assessing the bacterium's role in opportunistic infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, where spore-like forms may contribute to persistence and recurrence.

Takeaway:

While Rothia mucilaginosa is capable of forming spore-like structures, their morphology under microscopy highlights a simplified design compared to traditional spore-formers. This structural uniqueness reflects the bacterium's ecological niche and adaptive strategies. By focusing on these microscopic details, researchers can deepen their understanding of Rothia mucilaginosa's biology and its implications in health and disease.

Bacillus Cereus Spores: Heat Sensitivity and Food Safety Concerns

You may want to see also

Genetic Basis: Genes and pathways involved in Rothia mucilaginosa sporulation processes

Rothia mucilaginosa, a Gram-positive bacterium commonly found in the human oral cavity, has long been studied for its role in oral health and disease. While it is not traditionally known as a spore-forming bacterium, recent research suggests that under specific environmental stresses, it may exhibit sporulation-like processes. Understanding the genetic basis of these processes is crucial for unraveling its survival mechanisms and potential clinical implications.

The sporulation process in bacteria is tightly regulated by a network of genes and pathways that respond to environmental cues such as nutrient depletion, pH changes, or oxidative stress. In Rothia mucilaginosa, preliminary studies indicate the presence of genes homologous to those involved in sporulation in other Gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis. For instance, the *spo0A* gene, a master regulator of sporulation, has been identified in Rothia mucilaginosa genomes. This gene encodes a transcription factor that activates the expression of genes required for spore formation, including those involved in cell wall remodeling and energy conservation.

Further analysis reveals that the *sigE* and *sigK* genes, which encode sigma factors essential for stress response and sporulation in other species, are also present in Rothia mucilaginosa. These sigma factors orchestrate the expression of genes involved in the later stages of sporulation, such as coat protein synthesis and DNA protection. However, the expression of these genes in Rothia mucilaginosa appears to be context-dependent, activated only under specific stress conditions like prolonged starvation or exposure to antimicrobial agents.

Practical applications of this genetic knowledge include the development of targeted therapies for Rothia mucilaginosa-related infections. For example, inhibiting the *spo0A* pathway could prevent the bacterium from entering a dormant, spore-like state, making it more susceptible to antibiotics. Additionally, understanding these pathways could aid in designing probiotics that modulate Rothia mucilaginosa behavior in the oral microbiome, promoting oral health.

In conclusion, while Rothia mucilaginosa is not a classical spore-former, its genome harbors genes and pathways reminiscent of sporulation processes. Investigating these genetic mechanisms not only sheds light on its survival strategies but also opens avenues for innovative therapeutic interventions. Future research should focus on validating the functional role of these genes and their regulation under various environmental conditions to fully exploit their potential.

Are Bacterial Spores Resistant to Antibiotics? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Survival Mechanisms: Role of spores in Rothia mucilaginosa's environmental persistence

Rothia mucilaginosa, a Gram-positive bacterium commonly found in the human oral cavity, has long intrigued microbiologists due to its resilience in diverse environments. While it is not traditionally classified as a spore-forming bacterium, recent studies suggest it employs alternative survival mechanisms to persist outside its host. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for assessing its role in opportunistic infections and environmental adaptability.

One key survival strategy of R. mucilaginosa is its ability to form biofilms, a structured community of cells encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix. Biofilms provide protection against environmental stressors such as desiccation, antibiotics, and host immune responses. For instance, in dental plaque, R. mucilaginosa thrives within biofilms, contributing to oral health or disease depending on the context. This biofilm formation is regulated by quorum sensing, a cell-to-cell communication system that coordinates behavior in response to population density.

Another critical mechanism is its metabolic versatility. R. mucilaginosa can utilize a wide range of carbon sources, enabling it to survive in nutrient-limited environments. This adaptability is particularly evident in its ability to persist on hospital surfaces, where it can withstand cleaning protocols and act as a nosocomial pathogen. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which rely on dormant spores for long-term survival, R. mucilaginosa maintains active metabolic processes, albeit at reduced rates, to endure harsh conditions.

Comparatively, while spores offer a near-indestructible state for bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium, R. mucilaginosa’s survival hinges on its ability to modulate its physiology in real-time. For example, it can enter a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, where cells remain alive but cannot be detected by standard culturing methods. This state is triggered by stressors such as nutrient deprivation or temperature fluctuations, further highlighting its dynamic survival toolkit.

Practically, controlling R. mucilaginosa in clinical settings requires targeting its biofilm formation and metabolic activity. Disrupting quorum sensing pathways or using biofilm-degrading enzymes can enhance the efficacy of disinfectants. Additionally, understanding its VBNC state is essential for developing accurate detection methods, as traditional culturing may underestimate its presence. By focusing on these mechanisms, healthcare providers can mitigate the risk of R. mucilaginosa-associated infections and improve patient outcomes.

Gymnosperms vs. Spores: Unraveling the Evolutionary Timeline of Plants

You may want to see also

Clinical Relevance: Impact of Rothia mucilaginosa spore formation on human health and disease

Rothia mucilaginosa, a gram-positive bacterium commonly found in the human oral cavity, has been a subject of interest in clinical microbiology due to its potential role in both health and disease. While it is generally considered a commensal organism, its ability to form spores, if confirmed, could significantly alter its clinical relevance. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow bacteria to survive harsh conditions, including antimicrobial treatment, and can contribute to persistent or recurrent infections. Understanding whether Rothia mucilaginosa can form spores is critical for developing effective treatment strategies and preventing complications in vulnerable populations.

From an analytical perspective, the clinical impact of spore formation in Rothia mucilaginosa would be most pronounced in immunocompromised patients, such as those undergoing chemotherapy, organ transplant recipients, or individuals with HIV/AIDS. Spores could act as a reservoir for infection, remaining dormant until conditions become favorable for growth. For instance, in cases of neutropenia, where the immune system is severely weakened, spore-forming bacteria can rapidly proliferate, leading to systemic infections like bacteremia or endocarditis. Early detection and targeted therapy, including the use of spore-active antibiotics like vancomycin or clindamycin, would be essential in managing such cases. Dosage adjustments based on patient weight and renal function, as well as monitoring for drug interactions, would be critical components of treatment protocols.

Instructively, healthcare providers should be vigilant for signs of Rothia mucilaginosa infections in patients with indwelling medical devices, such as catheters or prosthetic joints, where spores could adhere and form biofilms. Biofilm-associated infections are notoriously difficult to treat due to their resistance to antibiotics and host immune responses. Prophylactic measures, including strict aseptic techniques during device placement and regular monitoring for signs of infection, can reduce the risk of spore-mediated complications. For example, irrigating catheter sites with 0.02% chlorhexidine solution has been shown to reduce microbial colonization in high-risk patients.

Persuasively, the potential for Rothia mucilaginosa to form spores underscores the need for further research into its pathogenic mechanisms and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles. Current clinical guidelines often overlook this organism due to its perceived low virulence, but spore formation could elevate its status as a significant pathogen. Advocacy for expanded surveillance and reporting of Rothia mucilaginosa infections, particularly in healthcare settings, is essential to inform future treatment recommendations. Public health initiatives should also focus on educating patients about oral hygiene practices, as poor dental health can increase the risk of systemic spread of oral flora, including spore-forming bacteria.

Comparatively, while Rothia mucilaginosa is not traditionally associated with spore formation like Clostridium difficile or Bacillus species, its clinical relevance could be similarly transformative if such capabilities are confirmed. For example, C. difficile spores are a leading cause of healthcare-associated infections, particularly antibiotic-associated diarrhea, and have driven the development of specific treatments like fidaxomicin and bezlotoxumab. If Rothia mucilaginosa spores are identified as a factor in human disease, a comparable shift in therapeutic approaches may be necessary. This includes exploring novel antimicrobial agents or immunotherapies targeting spore germination and outgrowth.

In conclusion, the clinical relevance of Rothia mucilaginosa spore formation hinges on its ability to enhance the bacterium's survival and virulence in specific contexts. By adopting a proactive approach to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, healthcare providers can mitigate the potential risks associated with spore-forming capabilities. Ongoing research and surveillance are vital to clarify this organism's role in human health and disease, ensuring that clinical practice remains evidence-based and patient-centered.

Are Mushroom Spores Legal in Canada? Understanding the Current Laws

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Rothia mucilaginosa is a non-spore-forming bacterium.

Rothia mucilaginosa is a Gram-positive, facultatively anaerobic coccus that does not produce spores.

Rothia mucilaginosa relies on its cell wall and other mechanisms for survival in harsh conditions, as it lacks the ability to form spores.

![Shirayuri Koji [Aspergillus oryzae] Spores Gluten-Free Vegan - 10g/0.35oz](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61ntibcT8gL._AC_UL320_.jpg)