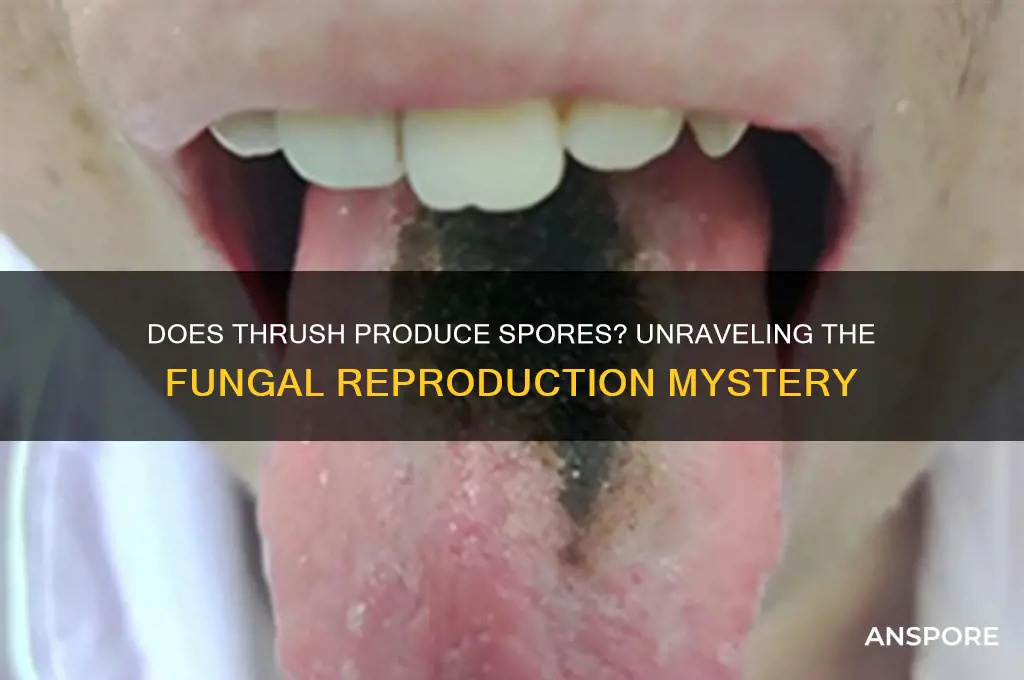

Thrush, a common fungal infection caused by the yeast *Candida albicans*, is often associated with symptoms like itching, redness, and white patches in the mouth or genital areas. While many fungi reproduce through spore formation, *Candida albicans* primarily reproduces through a process called budding, where new cells sprout from the parent cell. However, under certain environmental stresses or conditions, *Candida* can also produce spores, specifically chlamydospores, which are thick-walled, resistant structures that allow the fungus to survive harsh environments. Understanding whether and how thrush-causing fungi produce spores is crucial for comprehending their lifecycle, resilience, and potential treatment strategies.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Thrush spore formation process

Thrush, a common fungal infection caused by Candida species, is often misunderstood in terms of its reproductive mechanisms. While many fungi are known for producing spores as a means of dispersal and survival, Candida, the primary culprit behind thrush, does not form spores in the traditional sense. Instead, it relies on other methods to propagate and persist in its environment. This distinction is crucial for understanding how thrush spreads and how it can be effectively managed.

The reproductive process of Candida involves budding, where a small outgrowth (bud) forms on the parent cell, eventually detaching to become a new cell. This asexual method allows Candida to multiply rapidly under favorable conditions, such as warm, moist environments like the oral cavity or genital area. Unlike spore-forming fungi, which release airborne spores for long-distance dispersal, Candida’s budding process is localized, making direct contact or proximity a key factor in transmission. For instance, thrush in the mouth can spread through kissing or sharing utensils, while genital thrush may be transmitted sexually.

Understanding the absence of spore formation in Candida has practical implications for prevention and treatment. Since spores are not involved, reducing direct contact with infected individuals or surfaces is paramount. For oral thrush, this includes disinfecting items like toothbrushes and dentures, while genital thrush prevention involves safe sexual practices. Treatment typically focuses on antifungal medications, such as fluconazole (a single 150 mg dose for adults) or topical creams like clotrimazole, which target the fungal cells directly. Maintaining good hygiene and addressing underlying conditions, such as diabetes or weakened immunity, are also essential to prevent recurrence.

Comparatively, spore-forming fungi like Aspergillus or Penicillium pose different challenges due to their airborne spores, which can infiltrate the body through inhalation. Candida’s non-spore-forming nature means it is less likely to cause systemic infections in healthy individuals, though immunocompromised individuals remain at higher risk. This highlights the importance of tailoring prevention strategies to the specific biology of the pathogen. For example, while air filtration systems might be useful for spore-forming fungi, they are unnecessary for managing thrush.

In summary, while thrush does not produce spores, its efficient budding process ensures rapid proliferation in suitable environments. This knowledge informs targeted prevention and treatment strategies, emphasizing hygiene, direct contact reduction, and antifungal therapy. By focusing on these specifics, individuals can effectively manage and mitigate the risk of thrush, whether in oral or genital forms.

Pressure Cookers and Spores: Can Heat Destroy These Resilient Microorganisms?

You may want to see also

Types of spores produced by thrush

Thrush, a common fungal infection caused by Candida species, primarily affects mucous membranes, leading to symptoms like white patches in the mouth or genital discomfort. While Candida is well-known for its yeast form, it also produces spores under specific conditions. These spores, known as chlamydospores, are thick-walled, resilient structures that allow the fungus to survive harsh environments, such as dryness or temperature extremes. Understanding the types of spores produced by thrush is crucial for comprehending its persistence and recurrence, as these spores can remain dormant until conditions become favorable for growth.

Chlamydospores are the primary spore type associated with Candida species, including *Candida albicans*, the most common cause of thrush. These spores are typically formed in response to nutrient deprivation or other environmental stressors. Unlike the yeast form, which reproduces asexually by budding, chlamydospores are produced through a process called sporulation. They are larger and more durable, often appearing as terminal or intercalary cells in hyphae, the filamentous structures of the fungus. This adaptability ensures Candida’s survival in diverse settings, from the human body to external surfaces.

In clinical settings, the presence of chlamydospores can complicate thrush treatment. Antifungal medications like fluconazole (typically dosed at 150 mg for adults) or topical agents such as nystatin are effective against the yeast form but may struggle to eradicate spores. Chlamydospores’ thick walls make them resistant to many antifungals, necessitating prolonged or combination therapy. For recurrent thrush, healthcare providers often recommend strategies to disrupt spore survival, such as maintaining good oral hygiene, avoiding broad-spectrum antibiotics, and managing underlying conditions like diabetes.

Comparatively, other fungi like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium* produce spores (conidia) that are airborne and play a role in dissemination. Candida’s chlamydospores, however, are not airborne and rely on direct contact for transmission. This distinction highlights the localized nature of thrush infections and the importance of targeting spores in treatment. For instance, in infants with oral thrush, caregivers should sterilize pacifiers and bottles to prevent spore reintroduction, while adults with genital thrush should wash clothing and bedding in hot water to eliminate spores.

In summary, thrush-causing Candida species produce chlamydospores, resilient structures that ensure survival in adverse conditions. These spores differ from the yeast form in morphology, function, and resistance to treatment. Clinicians and patients must consider spore persistence when managing thrush, employing strategies like prolonged antifungal use and environmental decontamination. By understanding the unique role of chlamydospores, individuals can more effectively prevent and treat this persistent infection.

How to Defeat a Spore Lizard: Effective Strategies and Tips

You may want to see also

Conditions for thrush spore production

Thrush, a common fungal infection caused by Candida species, is often misunderstood in terms of its reproductive mechanisms. While Candida does not produce spores in the traditional sense like molds or other fungi, it reproduces through budding, where a small daughter cell forms on the parent cell and eventually detaches. However, certain conditions can influence the proliferation and dispersal of Candida cells, mimicking spore-like behavior in terms of spread and persistence. Understanding these conditions is crucial for managing and preventing thrush outbreaks.

Optimal Environmental Conditions for Candida Proliferation

Candida thrives in warm, moist environments, making areas like the mouth, genital tract, and skin folds prime locations for overgrowth. Temperature plays a critical role, with the fungus flourishing between 30°C and 37°C (86°F to 98.6°F). Humidity levels above 60% further encourage growth, as Candida requires moisture to maintain its cellular structure. pH levels are equally important; Candida prefers slightly acidic to neutral environments, typically between pH 4.0 and 7.0. These conditions not only support budding but also enhance the dispersal of cells, increasing the risk of infection spread.

Dietary and Host Factors Influencing Candida Growth

Dietary choices significantly impact Candida proliferation. High sugar intake, for instance, provides the fungus with its primary energy source, accelerating growth and budding. Similarly, excessive carbohydrate consumption can elevate blood glucose levels, creating an ideal environment for Candida. Host factors, such as a weakened immune system, hormonal imbalances (e.g., during pregnancy or due to oral contraceptive use), and antibiotic use, disrupt the natural microbial balance, allowing Candida to dominate. For example, antibiotics reduce beneficial bacteria in the gut and mouth, indirectly promoting Candida overgrowth.

Practical Tips to Mitigate Candida Proliferation

To minimize conditions conducive to Candida growth, maintain good hygiene, especially in skin folds and mucous membranes. Keep these areas dry and clean, using antifungal powders if necessary. Dietary modifications, such as reducing sugar and refined carbohydrate intake, can deprive Candida of its fuel source. Probiotics, particularly strains like Lactobacillus acidophilus, help restore microbial balance. For recurrent thrush, antifungal medications like fluconazole (150 mg single dose for adults) or clotrimazole (topical application for 1–2 weeks) may be prescribed. Always consult a healthcare provider for personalized treatment.

Comparative Analysis: Candida vs. Spore-Producing Fungi

Unlike spore-producing fungi such as Aspergillus or Penicillium, Candida lacks the ability to form spores. However, its resilience and adaptability allow it to survive harsh conditions, such as temperature fluctuations and nutrient deprivation, through biofilm formation. Biofilms act as protective matrices, enabling Candida cells to persist and disperse more effectively. While not spores, these biofilms contribute to the fungus’s tenacity and recurrence, making thrush challenging to eradicate. Understanding this distinction highlights the importance of targeting biofilms in treatment strategies.

Can Animals Produce Spores? Unraveling the Biology Behind Reproduction

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of spores in thrush lifecycle

Thrush, a common fungal infection caused by Candida species, primarily exists in its yeast form under normal conditions. However, certain Candida species, such as *Candida albicans*, can undergo a morphological transition to produce spores under specific environmental stresses. These spores, known as chlamydospores, play a critical role in the organism's survival and persistence. Unlike the yeast form, which is more susceptible to environmental changes, chlamydospores are highly resistant to adverse conditions, including temperature extremes, desiccation, and antimicrobial agents. This adaptability ensures the fungus can endure in harsh environments, waiting for favorable conditions to revert to the yeast form and resume active growth.

The formation of chlamydospores is a strategic response to stress, triggered by factors like nutrient deprivation, pH changes, or exposure to antifungal agents. This process, termed dimorphism, involves the thickening of cell walls and accumulation of storage materials, enhancing the spore's durability. For instance, in clinical settings, chlamydospores can survive on medical equipment and surfaces for extended periods, contributing to nosocomial infections. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for healthcare professionals, as it underscores the importance of rigorous disinfection protocols to prevent thrush outbreaks, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

From a practical standpoint, the spore-forming ability of Candida complicates treatment strategies. Standard antifungal medications, such as fluconazole, are effective against the yeast form but less so against chlamydospores. This resistance necessitates the use of broader-spectrum antifungals like amphotericin B or echinocandins in severe or recurrent cases. Additionally, maintaining good hygiene and environmental cleanliness can reduce spore persistence, lowering the risk of reinfection. For individuals prone to thrush, such as those with diabetes or HIV, regular monitoring and proactive management of underlying conditions are essential to disrupt the lifecycle facilitated by spores.

Comparatively, the role of spores in thrush contrasts with other fungal infections like aspergillosis, where airborne spores directly cause disease. In thrush, spores primarily serve as a survival mechanism rather than a direct pathogenic agent. This distinction highlights the need for tailored prevention and treatment approaches. For example, while air filtration systems are critical in managing aspergillosis, thrush control focuses on surface disinfection and personal hygiene. Recognizing these differences enables more effective management of fungal infections based on their unique lifecycle characteristics.

In conclusion, spores are a pivotal yet often overlooked aspect of the thrush lifecycle, enabling Candida to withstand hostile environments and evade eradication efforts. Their formation under stress conditions underscores the fungus's resilience, posing challenges for both treatment and prevention. By targeting both the yeast and spore forms through comprehensive strategies—including appropriate antifungal therapy, environmental control, and patient education—healthcare providers can more effectively manage thrush and reduce its recurrence. This dual-pronged approach is essential for breaking the cycle of infection and improving patient outcomes.

Spore's Effectiveness Against the Wolf of Saturn Six: A Detailed Analysis

You may want to see also

Health risks of thrush spores

Thrush, a common fungal infection caused by Candida species, primarily affects mucous membranes, leading to symptoms like white patches in the mouth or genital discomfort. While Candida does not produce spores in the same way as mold or other fungi, it can form yeast cells and hyphae, which contribute to its persistence and spread. Understanding the health risks associated with these fungal elements is crucial for prevention and management.

One of the primary health risks of Candida’s cellular structures is their ability to colonize and invade tissues. In immunocompromised individuals, such as those with HIV/AIDS, diabetes, or undergoing chemotherapy, Candida can enter the bloodstream, causing systemic candidiasis. This condition is life-threatening, with a mortality rate of up to 40% in severe cases. The yeast cells and hyphae adhere to medical devices like catheters, forming biofilms that shield them from antifungal treatments, making infections harder to eradicate.

For healthy individuals, the risks are generally localized but still significant. Oral thrush can impair eating and speaking, particularly in infants and the elderly, leading to malnutrition or dehydration. Genital thrush causes itching, burning, and pain during intercourse, affecting quality of life. Recurrent infections, often triggered by antibiotic use or hormonal changes, can become chronic, requiring prolonged treatment with antifungals like fluconazole (150 mg single dose for uncomplicated cases) or topical agents like clotrimazole.

Preventing exposure to Candida’s persistent forms is key. Practical tips include maintaining good oral hygiene, avoiding excessive sugar intake (which fuels Candida growth), and using probiotics to support a healthy microbiome. For those with recurrent infections, rotating antifungal treatments and addressing underlying conditions like diabetes can reduce risk. Regular monitoring of blood glucose levels and prompt treatment of infections are essential for vulnerable populations.

In summary, while Candida does not produce spores, its yeast cells and hyphae pose serious health risks, particularly in systemic infections. Awareness, early intervention, and targeted prevention strategies are vital to managing these risks effectively.

Can You Still Play Spore? Exploring the Game's Current Status

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, thrush (a fungal infection caused by Candida species) does not produce spores. Candida fungi reproduce primarily through budding or pseudohyphal growth.

Thrush-causing fungi, such as Candida albicans, reproduce asexually through budding, where a small outgrowth (bud) forms and eventually detaches to become a new cell.

No, spores are not involved in the spread of thrush. Thrush is typically transmitted through direct contact or overgrowth of existing Candida in the body, not via airborne spores.

While Candida species (responsible for thrush) do not produce spores, other fungi like Aspergillus or Penicillium do produce spores. However, these are unrelated to thrush infections.

No, thrush cannot be airborne like spore-producing fungi. It is a localized infection and does not spread through the air; it requires direct contact or internal overgrowth to occur.