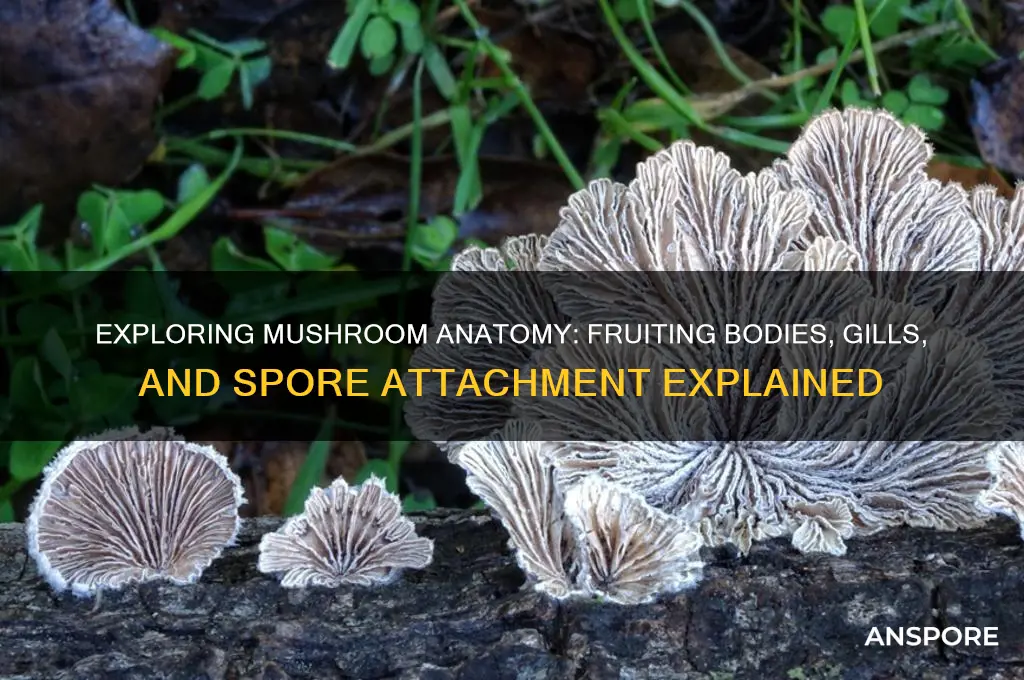

Fungi in the phylum Basidiomycota are characterized by their unique reproductive structures, which include fruiting bodies with spores attached to gills. These gills, typically found on the underside of mushroom caps, serve as the primary site for spore production and dispersal. The spores, produced on specialized cells called basidia, are released into the environment, allowing the fungus to propagate and colonize new habitats. This distinctive feature not only distinguishes Basidiomycota from other fungal groups but also plays a crucial role in their ecological functions, such as nutrient cycling and symbiotic relationships with plants. Understanding the structure and function of these fruiting bodies and gills provides valuable insights into the biology and diversity of these fascinating organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Division/Phylum | Basidiomycota |

| Subkingdom | Dikarya |

| Common Name | Gilled mushrooms, Agaricomycetes |

| Fruiting Body Structure | Spores attached to gills (lamellae) beneath the cap (pileus) |

| Spore Formation | Basidiospores produced on basidia (club-shaped structures on gills) |

| Gills Arrangement | Radiating from the stem (stipe) and attached to the underside of cap |

| Examples | Button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus), shiitake (Lentinula edodes) |

| Ecological Role | Saprotrophic (decomposers) or mycorrhizal (symbiotic with plants) |

| Reproduction | Sexual (via basidiospores) and asexual (fragmentation in some species) |

| Habitat | Forests, grasslands, decaying wood, soil |

| Economic Importance | Food (edible mushrooms), medicine, ecosystem services |

| Distinguishing Feature | Presence of gills as the spore-bearing surface |

| Taxonomic Class | Agaricomycetes (most gilled mushrooms belong to this class) |

Explore related products

$15.6

What You'll Learn

- Gill Structure and Function: Gills support spores, aiding in mushroom reproduction through efficient spore dispersal mechanisms

- Spore Attachment Methods: Spores adhere to gills via sterigmata, ensuring secure positioning for release

- Fruiting Body Development: Fruiting bodies mature, gills expand, and spores develop for dispersal

- Gill Arrangement Types: Gills can be free, attached, or decurrent, influencing spore distribution patterns

- Spore Dispersal Mechanisms: Air currents and water carry spores from gills, facilitating fungal propagation

Gill Structure and Function: Gills support spores, aiding in mushroom reproduction through efficient spore dispersal mechanisms

Mushrooms with gills are nature's ingenious solution to the challenge of spore dispersal. These delicate, radiating structures are not merely decorative; they are the launchpads for the next generation of fungi. Each gill is a thin, papery sheet lined with basidia—microscopic, club-shaped cells that produce and release spores. This design maximizes surface area, allowing a single mushroom to release millions of spores with minimal energy expenditure. For instance, the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*) can release up to 16 billion spores per fruiting body, a testament to the efficiency of this system.

To understand the mechanics of spore dispersal, consider the gill's role in aerodynamics. As air currents pass over the mushroom, they create a slight vacuum beneath the gills, lifting spores into the air. This process, known as "ballistospore discharge," ensures spores travel farther and with greater precision than if they were simply dropped. For optimal spore collection or observation, place a piece of dark paper beneath a mature mushroom cap overnight. By morning, you’ll see a distinct spore print—a radial pattern reflecting the gill arrangement. This simple experiment not only demonstrates gill function but also helps identify mushroom species based on spore color and arrangement.

While gills are marvels of efficiency, their structure is fragile, requiring specific environmental conditions to function optimally. High humidity is critical, as dry air can cause spores to stick to the basidia, reducing dispersal. In nature, mushrooms often fruit in damp, shaded areas to maintain this moisture. For cultivators, maintaining humidity levels between 85–95% during fruiting stages is essential. Additionally, avoid handling gills directly, as oils from human skin can disrupt spore release. Instead, use a small brush or air puffs to gently clean or examine them.

Comparing gilled mushrooms to their non-gilled counterparts highlights the evolutionary advantage of this structure. Puffballs, for example, rely on a single opening to release spores, often requiring external forces like raindrops or animal contact. In contrast, gilled mushrooms actively disperse spores through their intricate architecture, increasing the likelihood of colonization in new areas. This efficiency is why gilled species dominate forest floors and are more commonly encountered in foraging expeditions. By studying gill structure, we gain insights into fungal survival strategies and their role in ecosystems.

Finally, the gill's role in mushroom reproduction has practical implications for conservation and agriculture. Understanding spore dispersal mechanisms can inform strategies for protecting endangered fungi or controlling pathogenic species. For instance, knowing that spores are released in the early morning can guide timing for spore sampling or fungicide application. Similarly, in mushroom cultivation, optimizing airflow and humidity around gills can significantly increase yield. Whether you’re a mycologist, forager, or hobbyist, appreciating the gill's function transforms how we interact with and protect these vital organisms.

Are Laccaria Spores White? Unveiling the Truth About Their Color

You may want to see also

Spore Attachment Methods: Spores adhere to gills via sterigmata, ensuring secure positioning for release

Spores in certain fungi are not merely scattered haphazardly but are meticulously attached to gills via structures called sterigmata. These microscopic, peg-like extensions act as anchors, ensuring each spore remains securely positioned until optimal conditions trigger its release. This attachment method is a marvel of biological engineering, combining precision and efficiency to maximize spore dispersal.

Consider the process as a natural assembly line. Sterigmata form at the tips of basidia, the spore-producing cells, and act as temporary docking stations for spores. Each basidium typically supports four sterigmata, corresponding to the four haploid spores produced through meiosis. This one-to-one relationship guarantees that every spore is individually tethered, preventing clumping or premature detachment. The sterigma’s slender, elongated shape further optimizes spore alignment, positioning them for aerodynamic release when disturbed by wind, water, or passing animals.

To visualize this, imagine a row of spores suspended like beads on a thread, each bead perfectly spaced and ready to detach at the slightest provocation. This arrangement is not accidental but a result of evolutionary fine-tuning. For instance, in the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), sterigmata ensure spores are released in a controlled manner, increasing the likelihood of reaching new substrates. Without this mechanism, spores might aggregate, reducing their dispersal range and viability.

Practical observation of this process can be achieved through simple microscopy. A 40x–100x magnification of a gill’s surface reveals the orderly arrangement of spores on sterigmata, resembling a row of soldiers at attention. For educators or hobbyists, this exercise underscores the elegance of fungal reproduction and can be paired with discussions on adaptation and ecological roles.

In summary, sterigmata are not mere appendages but critical tools in the fungal life cycle. Their role in spore attachment exemplifies nature’s ingenuity, ensuring that each spore is poised for successful dispersal. Understanding this mechanism not only deepens appreciation for fungal biology but also highlights the precision underlying seemingly simple natural processes.

Pollen Grains vs. Spores: Unraveling Their Developmental Origins and Differences

You may want to see also

Fruiting Body Development: Fruiting bodies mature, gills expand, and spores develop for dispersal

The development of fruiting bodies in fungi is a fascinating process that culminates in the expansion of gills and the maturation of spores, ready for dispersal. This intricate journey begins with the colonization of a substrate by mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. As resources become available and environmental conditions align—typically involving adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrient levels—the mycelium initiates the formation of a primordium, the embryonic stage of the fruiting body. Over time, this structure differentiates into distinct parts, including the stipe (stem) and the pileus (cap), with gills developing beneath the cap. These gills serve as the spore-bearing surface, and their expansion increases the surface area available for spore production, maximizing dispersal potential.

Analyzing this process reveals a delicate balance of biological and environmental factors. For instance, the expansion of gills is not merely a physical growth but a strategic adaptation to optimize spore release. As the fruiting body matures, the gills increase in surface area, allowing for the attachment of millions of spores. Each spore is a microscopic unit of life, capable of surviving harsh conditions until it finds a suitable environment to germinate. The timing of gill expansion is critical; premature expansion risks spore loss, while delayed expansion reduces dispersal efficiency. This precision highlights the evolutionary sophistication of fungi, which have mastered the art of timing in their reproductive cycles.

From a practical standpoint, understanding fruiting body development is essential for mycologists, foragers, and even gardeners. For example, mushroom cultivators manipulate environmental conditions—such as humidity (maintained at 85–95%) and temperature (typically 20–25°C)—to encourage primordia formation and subsequent fruiting body development. For foragers, recognizing the stages of gill expansion can indicate the optimal time for harvesting, as mature gills signal peak spore development. However, caution is advised: consuming mushrooms with fully developed gills may result in a less palatable texture due to spore release. Thus, timing is as crucial in the kitchen as it is in nature.

Comparatively, the development of fruiting bodies in fungi contrasts with the reproductive strategies of plants and animals. While plants rely on flowers and seeds, and animals on mating and gestation, fungi employ a decentralized, spore-based system. This approach allows fungi to colonize diverse habitats, from forest floors to decaying wood, with remarkable efficiency. The gills, unique to certain fungal groups like agarics, provide a specialized mechanism for spore dispersal, akin to the role of pollen in plants. However, unlike pollen, which requires pollinators, fungal spores are dispersed passively by wind, water, or animals, showcasing the adaptability of fungi to their environments.

In conclusion, the maturation of fruiting bodies, the expansion of gills, and the development of spores represent a finely tuned reproductive strategy in fungi. This process is not only a marvel of biology but also a practical consideration for those who study, cultivate, or consume mushrooms. By observing and manipulating the conditions that drive fruiting body development, we can better appreciate the role of fungi in ecosystems and harness their potential in agriculture, medicine, and cuisine. Whether you’re a scientist, a forager, or a hobbyist, understanding this lifecycle offers insights into the hidden world of fungi and their indispensable contributions to life on Earth.

Can Your Dryer Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores from Clothes?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gill Arrangement Types: Gills can be free, attached, or decurrent, influencing spore distribution patterns

The arrangement of gills in fungi is a critical factor in spore dispersal, a process as intricate as it is essential for the organism's lifecycle. Gills, the thin, blade-like structures on the underside of mushroom caps, serve as the primary site for spore production. Their attachment to the stem—whether free, attached, or decurrent—dictates how spores are released and distributed. Understanding these gill arrangements offers insights into fungal ecology and aids in accurate species identification.

Consider the free gill arrangement, where gills are unattached to the stem. This design allows for maximum air circulation beneath the cap, facilitating efficient spore release. Species like the Agaricus bisporus (common button mushroom) exemplify this type. Here, spores are dispersed primarily through air currents, making free gills ideal for fungi in open environments. For foragers, recognizing free gills can help distinguish edible species from toxic look-alikes, as many Amanita species, known for their deadly toxicity, often have free gills.

In contrast, attached gills connect directly to the stem, creating a sealed environment beneath the cap. This arrangement reduces air circulation but ensures spores are released in a more controlled manner. The Boletus genus, known for its porous undersides rather than gills, demonstrates a similar principle. While not a gill-bearing fungus, its attachment mechanism highlights how structure influences function. For mycologists, studying attached gills can reveal adaptations to specific habitats, such as humid forests where controlled spore release is advantageous.

Decurrent gills, which extend downward along the stem, represent a unique adaptation. This arrangement increases the surface area for spore production, enhancing dispersal efficiency. Species like the Lactarius indigo (blue milk mushroom) showcase this feature. Decurrent gills are particularly useful in dense environments where air movement is limited. For hobbyists, identifying decurrent gills can be a key trait in mushroom classification, though caution is advised: some decurrent species, like certain Lactarius varieties, are inedible or mildly toxic.

Practical tips for observing gill arrangements include using a hand lens to examine the point of attachment and noting the cap’s distance from the stem. Foragers should avoid consuming mushrooms with ambiguous gill types, as misidentification can be dangerous. Mycologists can further analyze spore distribution by placing a mushroom cap on paper overnight to capture spore prints, revealing patterns influenced by gill arrangement. Whether for study or safety, understanding gill types is indispensable in the world of fungi.

Using Milky Spore in Gardens: Benefits, Application, and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Spore Dispersal Mechanisms: Air currents and water carry spores from gills, facilitating fungal propagation

Fungi with gills, such as mushrooms, have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to disperse their spores, ensuring the survival and propagation of their species. The gills, located on the underside of the fruiting body, serve as the primary site for spore production and release. Each gill is lined with countless basidia, the spore-bearing cells, which eject spores into the surrounding environment. This process, known as ballistospore discharge, propels spores away from the gill surface with remarkable force, often reaching speeds of up to 1 mm per second. However, this initial launch is only the first step in the journey of spore dispersal.

Air currents play a pivotal role in transporting spores over vast distances, a mechanism that is both passive and highly effective. Once released, spores are lightweight and easily carried by even the gentlest breeze. For example, a single mushroom can release millions of spores daily, and under optimal conditions, these spores can travel kilometers, colonizing new habitats and decomposing organic matter. To maximize this aerial dispersal, fungi often time their spore release to coincide with periods of higher wind activity, such as late morning or early afternoon. Gardeners and mycologists can capitalize on this by placing mushroom beds in open, windy areas to enhance spore distribution naturally.

Water, too, serves as a critical medium for spore dispersal, particularly in humid environments or near bodies of water. Raindrops falling on the gills dislodge spores, which are then carried away by runoff or absorbed into the soil. This method is especially advantageous for fungi in forested areas, where water flow through the understory can transport spores to nutrient-rich substrates. For those cultivating fungi, mimicking this process by gently misting mushroom beds can aid in spore release and local propagation. However, excessive moisture can lead to mold or bacterial contamination, so balance is key—aim for a light mist rather than a soaking.

Comparing air and water dispersal reveals distinct advantages for each. Air currents facilitate long-distance travel, enabling fungi to colonize distant or isolated habitats, while water dispersal is more localized but ensures spores reach moist, fertile environments ideal for germination. Fungi often employ both strategies, increasing their chances of successful reproduction. For instance, the common oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) thrives in both airy woodland edges and damp, decaying logs, showcasing the adaptability of these dispersal mechanisms.

In practical terms, understanding these mechanisms can inform conservation and cultivation efforts. Foraging enthusiasts should avoid trampling mushroom beds in windy conditions, as this disrupts spore release. Similarly, in controlled environments like mushroom farms, optimizing airflow and humidity levels can significantly boost yield. By observing and working with these natural processes, we can foster healthier fungal ecosystems and harness their benefits more effectively. Whether in the wild or in cultivation, the interplay of air and water in spore dispersal underscores the ingenuity of fungal survival strategies.

Unveiling Yeast Reproduction: Do They Form Spores to Multiply?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

This describes the reproductive structure of certain fungi, such as mushrooms, where the fruiting body (the visible part of the fungus) produces spores on gills, which are thin, blade-like structures located under the cap.

Basidiomycetes, a major group of fungi, commonly have this structure. Examples include mushrooms, toadstools, and bracket fungi.

Spores on gills are exposed to air, allowing them to disperse easily via wind, water, or animals. Once dispersed, spores can germinate and grow into new fungal organisms.

No, not all fungi have gills. Some, like puffballs, produce spores internally, while others, such as truffles, rely on animals for spore dispersal. Gills are specific to certain groups like Agaricomycetes.