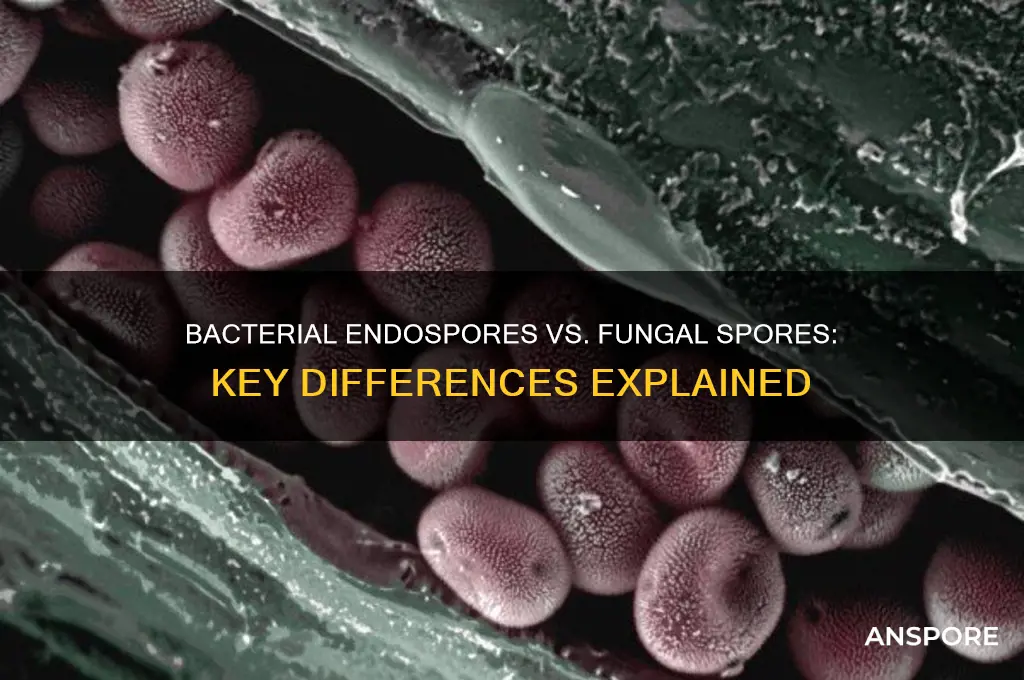

Bacterial endospores and fungal spores are both resilient structures produced by microorganisms to survive harsh environmental conditions, but they differ significantly in their structure, formation, and function. Bacterial endospores, formed by certain bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are highly resistant, dormant structures containing a copy of the bacterial genome and minimal cellular components, encased in multiple protective layers, including a thick spore coat and cortex. They are metabolically inactive and can withstand extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, and desiccation for extended periods. In contrast, fungal spores, produced by fungi such as molds and yeasts, are reproductive or dispersal structures that retain metabolic activity and are typically involved in propagation or survival. Fungal spores lack the extreme resistance of bacterial endospores and are generally less durable, though they can still survive adverse conditions. Additionally, fungal spores are often produced in larger quantities and are more diverse in morphology and function compared to the uniform, highly specialized bacterial endospores. These distinctions highlight the unique adaptations of each type of spore to their respective microbial lifestyles.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin | Bacterial endospores are formed by certain Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium) as a survival mechanism. Fungal spores are produced by fungi for reproduction and dispersal. |

| Function | Endospores serve as dormant, highly resistant structures to withstand harsh conditions. Fungal spores are primarily for reproduction, dispersal, and colonization of new environments. |

| Structure | Endospores have a core containing DNA, surrounded by a spore coat, cortex, and sometimes an exosporium. Fungal spores have a cell wall and may contain stored nutrients, but lack the layered structure of endospores. |

| Resistance | Endospores are highly resistant to heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals. Fungal spores are generally less resistant but can tolerate environmental stresses to varying degrees. |

| Size | Endospores are typically smaller (0.5–1.5 μm in diameter). Fungal spores vary widely in size depending on the species (e.g., yeast spores are smaller, while mold spores can be larger). |

| Reproduction | Endospores do not directly reproduce; they germinate into vegetative bacterial cells under favorable conditions. Fungal spores germinate and grow into new fungal individuals. |

| Location | Endospores are formed within the bacterial cell. Fungal spores are produced externally on specialized structures like sporangia, asci, or basidia. |

| Genetic Content | Endospores contain a copy of the bacterial genome. Fungal spores may contain haploid or diploid nuclei, depending on the fungal life cycle. |

| Germination Time | Endospores can remain dormant for years and germinate slowly under specific conditions. Fungal spores germinate more rapidly when exposed to suitable environmental cues. |

| Environmental Role | Endospores are primarily survival structures and do not contribute to ecosystem processes until germination. Fungal spores play active roles in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and ecosystem dynamics. |

| Shape and Morphology | Endospores are typically oval or spherical. Fungal spores exhibit diverse shapes (e.g., round, oval, filamentous) depending on the species. |

| Metabolic Activity | Endospores are metabolically inactive. Fungal spores may retain some metabolic activity, especially during dispersal and early germination stages. |

Explore related products

$9.25 $11.99

What You'll Learn

- Resistance Mechanisms: Bacterial endospores resist heat, radiation, chemicals; fungal spores resist desiccation, UV light

- Structure Differences: Endospores have thick protein coats; fungal spores have cell walls with chitin

- Formation Process: Endospores form inside bacteria; fungal spores form via meiosis or mitosis

- Survival Duration: Endospores survive centuries; fungal spores survive years to decades

- Germination Triggers: Endospores require nutrients; fungal spores need moisture and warmth

Resistance Mechanisms: Bacterial endospores resist heat, radiation, chemicals; fungal spores resist desiccation, UV light

Bacterial endospores and fungal spores are both survival structures, but their resistance mechanisms are tailored to distinct environmental challenges. Bacterial endospores, formed by certain bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*, are renowned for their ability to withstand extreme conditions. These structures resist heat up to 100°C for hours, ionizing radiation doses exceeding 1,000 kGy, and harsh chemicals like ethanol and formaldehyde. This resilience is attributed to their multi-layered structure, including a thick protein coat and a highly dehydrated core, which minimizes chemical reactivity and DNA damage. In contrast, fungal spores, produced by organisms such as *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, excel in resisting desiccation and UV light. Their cell walls contain chitin and melanin, which provide structural stability and protect against DNA-damaging UV radiation. While bacterial endospores are extreme survivalists in catastrophic environments, fungal spores thrive in prolonged arid conditions and sunlight exposure.

To illustrate these differences, consider practical scenarios. Bacterial endospores can survive autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, a process routinely used to sterilize medical equipment. This makes them a significant concern in healthcare settings, as they can cause infections like tetanus or botulism if not eradicated. Fungal spores, however, are more likely to persist in dry environments, such as soil or indoor air, where they can remain dormant for years. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores are commonly found in water-damaged buildings, posing risks to individuals with compromised immune systems. Understanding these resistance mechanisms is crucial for developing targeted eradication strategies, such as using higher temperatures for bacterial endospores or HEPA filters to capture fungal spores.

From an analytical perspective, the resistance mechanisms of these spores reflect their evolutionary adaptations. Bacterial endospores prioritize protection against sudden, intense stressors like heat and radiation, which are common in environments like hot springs or radioactive soils. Their ability to remain dormant for centuries underscores their role as a last-resort survival strategy. Fungal spores, on the other hand, are adapted to endure chronic, low-level stressors like desiccation and UV light, which are prevalent in surface environments. This distinction highlights how each spore type has evolved to address specific ecological niches, ensuring the survival of their respective organisms in diverse conditions.

For those seeking to mitigate the risks posed by these spores, practical tips can be derived from their resistance profiles. To eliminate bacterial endospores, ensure sterilization processes meet or exceed 121°C for at least 15 minutes, and use sporicidal chemicals like hydrogen peroxide or bleach for surface disinfection. For fungal spores, focus on humidity control (keeping indoor humidity below 60%) and UV-C light filtration systems, which can inactivate spores in air and water. Additionally, regular cleaning of HVAC systems and prompt remediation of water damage can prevent fungal spore proliferation. By tailoring interventions to the specific resistance mechanisms of each spore type, individuals and industries can effectively manage their risks.

In conclusion, the resistance mechanisms of bacterial endospores and fungal spores are a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. While bacterial endospores are engineered to withstand extreme, short-term stressors, fungal spores are optimized for long-term survival in harsh, dry conditions. Recognizing these differences not only deepens our understanding of microbial survival strategies but also informs practical approaches to control and eradication. Whether in a laboratory, hospital, or home, addressing these spores requires strategies that align with their unique vulnerabilities, ensuring safety and efficacy in diverse environments.

Do Algae Reproduce by Spores? Unveiling Aquatic Plant Reproduction Secrets

You may want to see also

Structure Differences: Endospores have thick protein coats; fungal spores have cell walls with chitin

Bacterial endospores and fungal spores, though both survival structures, differ fundamentally in their composition and architecture. Endospores are encased in a thick protein coat, primarily composed of keratin-like proteins, which provides exceptional resistance to heat, desiccation, and chemicals. This multi-layered structure, including an outer exosporium, a spore coat, and a cortex rich in peptidoglycan, ensures durability in harsh environments. In contrast, fungal spores rely on a cell wall fortified with chitin, a polysaccharide also found in arthropod exoskeletons. This chitinous layer offers structural integrity but lacks the extreme resilience of the endospore’s protein coat, making fungal spores more susceptible to environmental stressors.

To understand the practical implications, consider their survival strategies. Bacterial endospores, such as those formed by *Clostridium botulinum*, can withstand temperatures exceeding 100°C for extended periods, a feat attributed to their proteinaceous armor. This makes them challenging to eliminate in food processing, necessitating methods like autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes. Fungal spores, like those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, while hardy, are less resistant to heat and typically require temperatures above 60°C for inactivation. Their chitin-based cell walls, though robust, are more vulnerable to mechanical disruption and certain antifungal agents, such as chitinase enzymes, which degrade their structural integrity.

From an evolutionary perspective, these structural differences reflect distinct survival priorities. Bacterial endospores prioritize longevity and resistance, enabling them to persist in soil, water, and even outer space for millennia. Fungal spores, on the other hand, emphasize dispersal and rapid germination, leveraging their chitinous walls to withstand brief exposure to adverse conditions while remaining primed for growth upon encountering favorable environments. This trade-off between durability and adaptability underscores the divergent roles these structures play in their respective life cycles.

For those working in microbiology, agriculture, or food safety, understanding these structural nuances is critical. For instance, in sterilizing laboratory equipment, the presence of bacterial endospores demands more rigorous protocols than fungal spores. Similarly, in agriculture, managing fungal pathogens may involve targeting their chitin-rich cell walls with specific fungicides, whereas bacterial contaminants require more extreme measures. By recognizing these differences, professionals can tailor strategies to effectively control or eliminate these resilient forms of life.

Storing Extra Spores in Syringes: Best Practices and Tips

You may want to see also

Formation Process: Endospores form inside bacteria; fungal spores form via meiosis or mitosis

Bacterial endospores and fungal spores are both survival structures, but their formation processes reveal stark differences in complexity and cellular mechanisms. Endospores are formed entirely within the bacterial cell, acting as a protective shell that encapsulates the bacterium’s genetic material and a minimal set of enzymes. This process, known as sporulation, is triggered by nutrient deprivation and involves a series of asymmetric cell divisions, culminating in the creation of a highly resistant spore. In contrast, fungal spores are produced through either meiosis (in sexual reproduction) or mitosis (in asexual reproduction), depending on the species and environmental conditions. These spores are external structures, often formed at the tips of specialized hyphae or within fruiting bodies, and are designed for dispersal rather than immediate survival within the parent cell.

To illustrate, consider *Bacillus subtilis*, a bacterium that forms endospores when starved of nutrients. The process begins with the bacterium replicating its DNA and dividing asymmetrically to create a smaller cell (the forespore) within the larger mother cell. The forespore is then engulfed by the mother cell, which synthesizes multiple protective layers, including a cortex rich in peptidoglycan and a proteinaceous coat. This internal formation ensures the endospore remains a self-contained unit, capable of withstanding extreme conditions like heat, radiation, and desiccation. Conversely, fungi like *Aspergillus* produce spores through mitosis, where the nucleus divides, and the resulting cells are packaged into conidia—external spores that are easily dispersed by wind or water. This external formation prioritizes propagation over the immediate survival of the parent organism.

The distinction in formation processes has practical implications for control and eradication. Endospores, due to their internal and multilayered structure, are notoriously difficult to eliminate, requiring high temperatures (e.g., autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes) or strong chemical agents like bleach. Fungal spores, while still resilient, are generally more susceptible to environmental factors such as UV light, desiccation, and antifungal agents. For instance, surface disinfection with a 70% ethanol solution can effectively inactivate many fungal spores, whereas bacterial endospores would require more aggressive measures. Understanding these differences is crucial for industries like food safety, healthcare, and agriculture, where controlling microbial contamination is paramount.

From an evolutionary perspective, the internal formation of endospores reflects bacteria’s need to survive in harsh, unpredictable environments. By encapsulating their genetic material within a protective shell, bacteria ensure their long-term survival even when the parent cell perishes. Fungal spores, on the other hand, are adapted for dispersal and colonization, reflecting fungi’s role as decomposers and symbionts in diverse ecosystems. This divergence in strategy highlights the distinct ecological niches these microorganisms occupy. For example, bacterial endospores can remain dormant in soil for decades, while fungal spores rapidly colonize new substrates, such as decaying plant matter or living hosts.

In summary, the formation of bacterial endospores and fungal spores underscores their unique survival strategies. Endospores are internally produced, highly resistant structures designed for long-term survival, while fungal spores are externally formed and optimized for dispersal and rapid colonization. Recognizing these differences not only advances our understanding of microbial biology but also informs practical approaches to managing these organisms in various settings. Whether in a laboratory, hospital, or agricultural field, tailoring strategies to the specific formation and function of these spores can lead to more effective control and utilization of these remarkable microbial structures.

How Ferns Disperse Spores: Unveiling the Ancient Reproduction Process

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Survival Duration: Endospores survive centuries; fungal spores survive years to decades

Bacterial endospores and fungal spores are both remarkable survival structures, but their longevity in harsh conditions differs dramatically. Endospores, produced by certain bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*, can persist for centuries, even millennia, under extreme conditions such as desiccation, radiation, and high temperatures. For instance, viable endospores of *Bacillus* species have been isolated from 25-million-year-old amber and 10,000-year-old sediments, showcasing their unparalleled resilience. This extraordinary survival capability is attributed to their multilayered protective coat, low water content, and DNA repair mechanisms. In contrast, fungal spores, while highly adaptable, typically survive for years to decades. For example, *Aspergillus* spores can persist in soil for up to 20 years, but their survival is more dependent on environmental factors like humidity and temperature. This stark difference in survival duration highlights the unique evolutionary strategies of these microorganisms.

To understand the practical implications, consider the challenges in sterilizing environments where these spores are present. Endospores require extreme measures, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, to ensure complete inactivation. Even then, their resistance can complicate processes in industries like food preservation and medical sterilization. Fungal spores, while less resilient, still pose challenges in indoor environments, where they can cause allergies and infections if not managed properly. For instance, *Stachybotrys* spores, known for their role in "sick building syndrome," can survive on damp surfaces for years, necessitating thorough mold remediation. This comparison underscores the need for tailored strategies to address each type of spore effectively.

From an evolutionary perspective, the extended survival of endospores reflects their role as a last-resort mechanism for bacterial persistence in unpredictable environments. Their ability to remain dormant for centuries allows them to outlast adverse conditions, ensuring the species' continuity. Fungal spores, on the other hand, are more geared toward rapid dispersal and colonization, with survival durations optimized for exploiting transient opportunities. This difference is evident in their ecological roles: bacterial endospores are often found in nutrient-poor soils and extreme habitats, while fungal spores thrive in diverse ecosystems, from forests to human-built environments. Understanding these adaptations can inform strategies for controlling spore-related issues, from agricultural pest management to public health interventions.

For those dealing with spore contamination, whether in a laboratory, hospital, or home, the survival duration of these structures is a critical factor. Endospores require rigorous decontamination protocols, such as the use of sporicidal agents like hydrogen peroxide or chlorine dioxide, to ensure eradication. Fungal spores, while less resilient, may necessitate repeated cleaning and environmental adjustments, such as reducing humidity levels below 60%, to prevent regrowth. Practical tips include using HEPA filters to capture airborne spores and regularly inspecting areas prone to moisture accumulation. By recognizing the distinct survival capabilities of endospores and fungal spores, individuals can implement more effective and targeted control measures, minimizing the risk of recurrence.

In summary, the survival duration of bacterial endospores and fungal spores is a testament to their unique evolutionary strategies. While endospores can endure for centuries, fungal spores are limited to years or decades. This difference has profound implications for sterilization, environmental management, and public health. By understanding these distinctions, we can develop more effective strategies to control and mitigate the risks associated with these resilient microorganisms. Whether in a scientific, industrial, or domestic setting, this knowledge empowers us to tackle spore-related challenges with precision and confidence.

Surviving Extremes: Can Spores Withstand Heat, Drying, and Disinfection?

You may want to see also

Germination Triggers: Endospores require nutrients; fungal spores need moisture and warmth

Bacterial endospores and fungal spores, though both dormant survival structures, awaken under distinct conditions. Endospores, the resilient forms of certain bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*, remain inert until they detect specific nutrients. These nutrients act as molecular keys, unlocking the metabolic processes necessary for germination. In contrast, fungal spores, such as those from molds and yeasts, require a combination of moisture and warmth to transition from dormancy to active growth. This fundamental difference in germination triggers reflects their evolutionary adaptations to diverse environments.

Consider the practical implications of these triggers. For endospores, nutrient availability is critical. In laboratory settings, researchers often use nutrient-rich media containing amino acids, purines, or pyrimidines to induce germination. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* endospores typically require a concentration of 10–20 mM of L-valine for effective germination. In natural environments, endospores may remain dormant in soil or water for years, waiting for organic matter to provide the necessary nutrients. This specificity ensures that endospores only activate when conditions are favorable for survival and proliferation.

Fungal spores, however, are more responsive to environmental cues like humidity and temperature. For example, mold spores often germinate at relative humidity levels above 70% and temperatures between 20–30°C (68–86°F). Homeowners combating mold growth must address these factors by reducing indoor humidity with dehumidifiers and maintaining cooler temperatures. Similarly, agricultural practices often involve controlling moisture levels in soil and storage facilities to prevent fungal spore germination in crops. This sensitivity to moisture and warmth allows fungal spores to thrive in environments where water and heat are abundant, such as damp basements or decaying organic matter.

The distinct germination triggers of endospores and fungal spores also influence their ecological roles. Endospores, with their nutrient-dependent awakening, are often associated with nutrient-limited environments like soil or aquatic systems. Their ability to persist in harsh conditions makes them key players in nutrient cycling and ecosystem resilience. Fungal spores, on the other hand, dominate environments where moisture and warmth are consistent, such as forests or food storage areas. Their rapid germination in response to these cues enables fungi to decompose organic material efficiently, contributing to nutrient recycling in ecosystems.

Understanding these triggers has practical applications in fields like medicine, food safety, and environmental management. For instance, sterilizing medical equipment requires conditions that not only kill vegetative bacteria but also destroy endospores, which are notoriously resistant to heat and chemicals. High-pressure steam sterilization at 121°C (250°F) for 15–30 minutes is commonly used to achieve this. Conversely, preventing fungal growth in food storage involves controlling humidity and temperature, such as storing grains at moisture levels below 14% and temperatures under 15°C (59°F). By targeting the specific germination triggers of these spores, we can develop more effective strategies to manage their presence in various contexts.

How Spores Impact Different Steel Types: A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bacterial endospores are highly resistant, dormant structures formed within a bacterial cell, while fungal spores are reproductive or dispersal structures produced externally by fungi.

Bacterial endospores are extremely resistant to heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals, whereas fungal spores are generally less resistant but can survive in specific environmental conditions like soil or air.

Bacterial endospores serve as a survival mechanism during harsh conditions, allowing bacteria to remain dormant until favorable conditions return, while fungal spores primarily function for reproduction and dispersal to new environments.