Algae, a diverse group of photosynthetic organisms, exhibit a wide range of reproductive strategies, and one common method is through the production of spores. These spores, often referred to as algal spores or zoospores, are specialized cells capable of developing into new individuals under favorable conditions. Unlike plants that typically reproduce via seeds, many algae species release spores as a means of dispersal and propagation. This reproductive approach allows algae to thrive in various environments, from aquatic ecosystems to damp terrestrial habitats, ensuring their survival and widespread distribution across the globe. The process of spore formation and release is a fascinating aspect of algal biology, contributing to their ecological success and adaptability.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Algae can reproduce both sexually and asexually. |

| Asexual Reproduction | Some algae reproduce asexually via spores (e.g., zygotes or aplanospores). |

| Sexual Reproduction | Involves the fusion of gametes, but not always resulting in spores. |

| Types of Spores | Zygospores, aplanospores, hypnospores, and akinetes (depending on species). |

| Function of Spores | Spores serve as dormant, resistant structures for survival in harsh conditions. |

| Species Variation | Not all algae reproduce via spores; methods vary widely among species. |

| Examples | Green algae (e.g., Chlamydomonas) and red algae may produce spores. |

| Environmental Factors | Sporulation is often triggered by environmental stress or nutrient depletion. |

| Ecological Role | Spores aid in dispersal and long-term survival in diverse habitats. |

| Latest Research | Ongoing studies focus on spore formation mechanisms and genetic control in algae. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: How algae cells form spores through mitosis or meiosis for reproduction

- Types of Spores: Classification of spores (e.g., zoospores, aplanospores, hypnospores) in algae

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like light, temperature, and nutrients that induce spore formation

- Dispersal Mechanisms: How algae spores spread via water, wind, or animals to new habitats

- Survival Strategies: Role of spores in algae survival during harsh conditions (e.g., drought, cold)

Sporulation Process: How algae cells form spores through mitosis or meiosis for reproduction

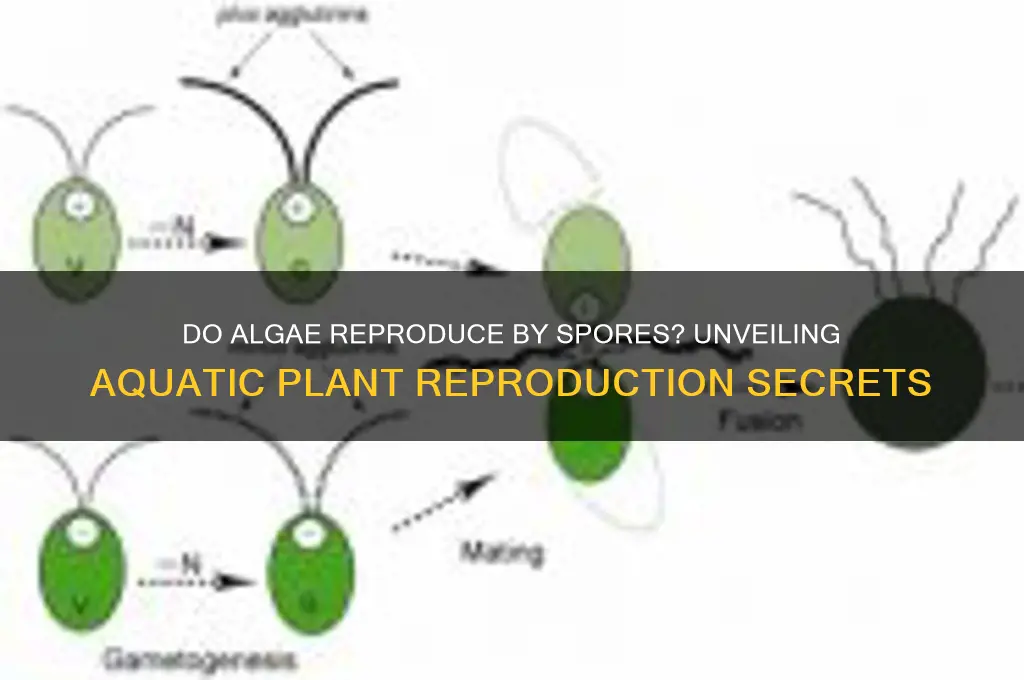

Algae, a diverse group of photosynthetic organisms, employ various reproductive strategies, including the formation of spores. The sporulation process is a critical mechanism through which algae cells produce spores, ensuring survival and dispersal in diverse environments. This process can occur through either mitosis or meiosis, each serving distinct purposes in the algae's life cycle.

The Mitosis Pathway: Asexual Sporulation

In favorable conditions, many algae species reproduce asexually via mitosis to form spores called mitospores or conidia. This process begins with a single algal cell undergoing repeated mitotic divisions, resulting in the production of genetically identical daughter cells. These cells then develop into spores, often encased in protective walls to withstand harsh conditions. For example, *Chlamydomonas*, a green alga, forms zoospores equipped with flagella for motility, allowing them to seek out optimal habitats. Asexual sporulation is rapid and efficient, enabling algae populations to expand quickly in nutrient-rich environments. To encourage this process in laboratory settings, maintain a temperature range of 20–25°C and provide a light intensity of 50–100 μmol photons/m²/s, as these conditions optimize cell division and spore formation.

The Meiosis Pathway: Sexual Sporulation

Under stress or in response to environmental cues, algae often shift to sexual reproduction, employing meiosis to form meiospores, such as zygotes or tetrads. Meiosis involves the fusion of gametes, followed by genetic recombination, producing spores with unique genetic combinations. This diversity enhances the population's resilience to changing conditions. For instance, *Ulva* (sea lettuce) releases gametes that fuse to form a zygote, which develops into a resistant spore capable of surviving desiccation and temperature extremes. To induce sexual sporulation, manipulate environmental factors such as nutrient depletion or temperature shifts (e.g., reducing temperature to 15°C for 48 hours). This triggers the transition from vegetative growth to reproductive stages.

Comparative Analysis: Mitosis vs. Meiosis in Sporulation

While mitosis ensures rapid proliferation of genetically identical spores, meiosis fosters genetic diversity through recombination. Mitosis is ideal for stable environments where adaptation is less critical, whereas meiosis is advantageous in unpredictable habitats, enabling algae to evolve and survive. For instance, in aquaculture, asexual sporulation is favored for consistent biomass production, while sexual sporulation is harnessed for breeding programs to develop stress-tolerant strains. Understanding these pathways allows researchers to manipulate algal growth for applications like biofuel production or wastewater treatment.

Practical Tips for Observing Sporulation

To observe sporulation in algae, start by culturing a species like *Chlorella* or *Spirulina* in a nutrient-rich medium (e.g., BG-11 broth). For mitosis, maintain optimal growth conditions and monitor cell density daily using a hemocytometer. For meiosis, introduce stress by reducing nitrogen levels or altering light cycles. Stain samples with 0.1% calcofluor white to visualize spore walls under a fluorescence microscope. Document changes in cell morphology and spore formation over 7–14 days to track the sporulation process. This hands-on approach provides valuable insights into algae's reproductive strategies and their ecological significance.

Takeaway: The Dual Role of Sporulation

The sporulation process in algae, whether through mitosis or meiosis, is a testament to their adaptability. By forming spores, algae ensure both rapid proliferation and genetic diversity, balancing stability and evolution. This dual strategy underscores their success in diverse ecosystems, from freshwater ponds to marine environments. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, understanding sporulation opens doors to harnessing algae's potential in biotechnology, ecology, and beyond.

Are Pine Cones Spores? Unraveling Nature's Seed Dispersal Mysteries

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Classification of spores (e.g., zoospores, aplanospores, hypnospores) in algae

Algae, a diverse group of photosynthetic organisms, employ various reproductive strategies, and spores play a pivotal role in their life cycles. Among the myriad types of spores, zoospores, aplanospores, and hypnospores stand out due to their distinct characteristics and ecological significance. Each type is adapted to specific environmental conditions, ensuring the survival and propagation of algal species across diverse habitats.

Zoospores: The Swimmers of Algal Reproduction

Zoospores are perhaps the most dynamic of algal spores, equipped with flagella that enable them to swim through water. This motility is a critical adaptation for species in aquatic environments, allowing them to disperse efficiently in search of favorable conditions. For instance, species like *Chlamydomonas* rely on zoospores to colonize new areas rapidly. However, their reliance on water for movement limits their effectiveness in drier environments. Zoospores are typically short-lived, prioritizing quick dispersal over long-term survival. To observe zoospores in action, researchers often use microscopes to track their movement patterns, which can vary based on factors like temperature and nutrient availability.

Aplanospores: The Dormant Travelers

In contrast to zoospores, aplanospores lack flagella and are non-motile. This characteristic makes them less immediately dispersive but more resilient in harsh conditions. Aplanospores are often produced when environmental stressors, such as nutrient depletion or temperature extremes, threaten the parent organism. For example, *Ulothrix* species form aplanospores as a survival mechanism during unfavorable seasons. These spores can remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for conditions to improve. Their thick cell walls provide protection against desiccation and predation, making them ideal for terrestrial or ephemeral water bodies. Cultivating algae that produce aplanospores often involves simulating stress conditions in controlled environments to induce spore formation.

Hypnospores: The Long-Term Survivors

Hypnospores represent the pinnacle of algal spore resilience, designed for long-term survival in extreme environments. These spores are characterized by their ability to withstand desiccation, freezing temperatures, and even exposure to UV radiation. Species like *Zygnema* produce hypnospores as a response to prolonged stress, ensuring genetic continuity across generations. Unlike zoospores and aplanospores, hypnospores are rarely produced under normal conditions, requiring specific triggers such as prolonged drought or salinity changes. Their robust structure and metabolic dormancy make them challenging to study, but they are invaluable for understanding algal survival strategies. For practical applications, hypnospores are often used in biotechnology to study stress tolerance mechanisms.

Comparative Analysis and Practical Implications

While zoospores excel in dispersal, aplanospores and hypnospores prioritize survival under stress. Each spore type reflects the evolutionary adaptations of algae to their environments. For researchers and cultivators, understanding these distinctions is crucial for optimizing algal growth and preservation. For instance, inducing zoospore production can enhance algal spread in aquaculture, while hypnospore studies can inform conservation efforts in arid regions. By classifying and studying these spores, we gain insights into algal ecology and unlock potential applications in biotechnology, agriculture, and environmental science. Whether you’re a scientist or an enthusiast, recognizing the unique roles of zoospores, aplanospores, and hypnospores is key to appreciating the complexity of algal reproduction.

Are Spores Inactive Bacteria? Unveiling Their Dormant Survival Mechanism

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: Factors like light, temperature, and nutrients that induce spore formation

Algae, like many organisms, have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to respond to environmental cues, ensuring their survival and proliferation. Among these cues, light, temperature, and nutrient availability play pivotal roles in triggering spore formation, a critical reproductive strategy. Understanding these environmental triggers can provide insights into algae’s adaptability and inform applications in biotechnology, ecology, and aquaculture.

Light: The Master Regulator of Spore Formation

Light is perhaps the most influential environmental factor in inducing spore formation in algae. Different wavelengths and intensities act as signals for algae to transition from vegetative growth to reproductive phases. For instance, red light (660 nm) often promotes sporulation in species like *Chlamydomonas reinhardtii*, while blue light (450 nm) can inhibit it. In natural settings, seasonal changes in daylight duration and intensity trigger spore formation, preparing algae for dispersal or dormancy. For laboratory cultures, researchers manipulate light cycles—typically 12 hours of light followed by 12 hours of darkness—to optimize spore production. Practical tip: Use LED grow lights with adjustable spectra to mimic natural conditions and enhance spore yield in controlled environments.

Temperature: A Delicate Balance for Sporulation

Temperature acts as a fine-tuned trigger, with specific ranges inducing spore formation in various algal species. For example, *Ulva* (sea lettuce) initiates spore production at temperatures between 18°C and 22°C, while higher temperatures (above 25°C) can inhibit sporulation. Conversely, some cold-tolerant species, like *Chlamydomonas nivalis*, form spores in response to freezing temperatures as a survival mechanism. In aquaculture, maintaining water temperatures within 2-3°C of the optimal range for the target species can significantly increase spore viability. Caution: Sudden temperature fluctuations can stress algae, leading to reduced spore formation or viability, so gradual acclimation is key.

Nutrients: The Fuel for Spore Development

Nutrient availability, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus, directly influences spore formation in algae. Nitrogen depletion, for instance, is a well-known trigger for sporulation in species like *Dunaliella salina*. When nitrogen levels drop below 0.1 mg/L, cells redirect resources toward spore production. Similarly, phosphorus limitation can induce sporulation in *Chlorella*, though the threshold varies by species. In practical applications, nutrient-limited media—achieved by reducing nitrogen or phosphorus concentrations by 70-90%—can be used to induce spore formation in algal cultures. Takeaway: Nutrient manipulation is a powerful tool for controlling reproductive cycles in algae, with precise adjustments yielding predictable results.

Comparative Analysis: Synergistic Effects of Environmental Triggers

While light, temperature, and nutrients each play distinct roles, their combined effects often determine the success of spore formation. For example, *Ulva* requires both optimal temperature (20°C) and high light intensity (100 μmol/m²/s) to maximize spore production, with nutrient availability acting as a secondary modulator. In contrast, *Chlamydomonas* can sporulate under low light conditions if temperatures are favorable and nutrients are scarce. This interplay highlights the importance of holistic environmental management in both natural and artificial systems. Practical tip: Monitor and adjust all three factors simultaneously for consistent spore yields, especially in large-scale algal cultivation.

By understanding and manipulating light, temperature, and nutrient availability, researchers and practitioners can effectively induce spore formation in algae. These environmental triggers not only reveal the adaptive strategies of algae but also offer practical tools for optimizing algal production in biotechnology, biofuel research, and ecological restoration. Whether in a laboratory or a natural setting, precise control of these factors ensures successful sporulation, unlocking the full reproductive potential of these versatile organisms.

Mold Spores: Are They Truly Everywhere in Our Environment?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dispersal Mechanisms: How algae spores spread via water, wind, or animals to new habitats

Algae, often overlooked in the grand tapestry of life, employ ingenious strategies to disperse their spores and colonize new habitats. Unlike plants with seeds, algae rely on microscopic spores that are lightweight and easily transported. These spores are not just passive travelers; they are designed to withstand harsh conditions, ensuring survival during their journey. Understanding how these spores move—whether through water, wind, or animals—reveals the adaptability and resilience of algae in diverse ecosystems.

Water serves as the primary highway for algal spore dispersal, particularly in aquatic environments. For instance, phytoplankton, microscopic algae in oceans and lakes, release spores that drift with currents, tides, and waves. This passive transport allows them to reach nutrient-rich areas or new bodies of water. In freshwater systems, spores of filamentous algae like *Spirogyra* attach to water droplets or small organisms, hitching a ride to distant locations. Even in terrestrial habitats, rainwater can splash spores from one moist surface to another, facilitating their spread. To maximize this mechanism, algae often produce spores in high quantities, increasing the likelihood of successful dispersal.

Wind, though less dominant than water, plays a crucial role in dispersing algal spores, especially for species in damp terrestrial environments. Algae like *Zygnema* and *Klebsormidium*, which thrive on moist soil or rocks, release spores that are lightweight and aerodynamic. These spores can be carried over short distances by gentle breezes or lifted into the atmosphere during storms, traveling miles before settling in new habitats. Interestingly, some algae produce spores with sticky coatings or filamentous structures that enhance their adherence to surfaces, ensuring they don’t blow away prematurely. For gardeners or land managers, this highlights the importance of monitoring wind patterns when dealing with algal blooms or invasive species.

Animals, both large and small, act as unwitting carriers of algal spores, contributing to their dispersal in unexpected ways. Aquatic animals like fish, amphibians, and crustaceans can transport spores on their bodies or in their digestive systems as they move between water bodies. Terrestrial animals, including insects and birds, may pick up spores while foraging in moist environments and deposit them elsewhere. For example, snails and slugs are known to carry algal spores on their slimy trails, leaving behind a path of potential new colonies. This symbiotic relationship underscores the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the role of animals in shaping algal distribution.

In practical terms, understanding these dispersal mechanisms can inform strategies for managing algal populations, whether for conservation or control. For instance, in aquaculture, preventing the spread of harmful algal blooms might involve limiting water flow between ponds or treating water to reduce spore viability. In landscaping, avoiding overwatering and managing windbreaks can minimize the spread of unwanted algal species. By studying these mechanisms, we gain insights into the remarkable ways algae ensure their survival and proliferation, even in the most challenging environments.

Can Your AC Unit Spread Mold Spores in Your Home?

You may want to see also

Survival Strategies: Role of spores in algae survival during harsh conditions (e.g., drought, cold)

Algae, despite their simplicity, have evolved remarkable survival strategies to endure harsh environmental conditions. One of their most effective mechanisms is the production of spores, which serve as resilient, dormant structures capable of withstanding extreme stressors such as drought, cold, and desiccation. These spores are not merely reproductive units but also act as survival capsules, ensuring the continuity of algal species in environments that would otherwise be inhospitable. For instance, desiccation-tolerant algae like *Chlamydomonas* form thick-walled zygospores that can remain viable for years, reactivating when conditions improve.

The process of spore formation in algae is a highly regulated response to environmental cues. When conditions deteriorate—such as water scarcity or freezing temperatures—algae initiate sporulation, a process that involves cellular differentiation and the accumulation of protective compounds like trehalose and lipids. These compounds act as cryoprotectants and desiccants, shielding the spore’s genetic material and metabolic machinery. For example, in snow algae, spores accumulate carotenoids to protect against UV radiation and freezing temperatures, allowing them to survive in polar and alpine regions. This adaptive strategy highlights the precision with which algae tailor their survival mechanisms to specific environmental challenges.

Comparatively, the role of spores in algal survival contrasts with other microbial survival strategies, such as cyst formation in bacteria or dormancy in fungi. While bacterial cysts and fungal spores share similarities with algal spores in terms of dormancy, algal spores often exhibit greater resilience due to their unique cellular composition and metabolic shutdown. For instance, algal spores can tolerate water loss to levels as low as 1-10% of their dry weight, a feat unmatched by most other microorganisms. This extreme tolerance underscores the evolutionary advantage of sporulation as a survival strategy in algae.

Practical applications of algal spore survival strategies are emerging in biotechnology and agriculture. By understanding how algae protect their spores, scientists are developing methods to enhance crop resilience to drought and cold. For example, genetic engineering of crops to express algal cryoprotectant proteins could improve their survival in freezing conditions. Additionally, algal spores are being explored as bioindicators for environmental monitoring, as their presence or absence can signal changes in water availability or temperature. To harness these benefits, researchers recommend studying spore-forming algae under controlled stress conditions, such as exposing *Dunaliella* species to gradual desiccation to observe sporulation dynamics.

In conclusion, the role of spores in algal survival during harsh conditions is a testament to the ingenuity of nature’s solutions. By forming spores, algae not only ensure their persistence but also contribute to ecosystem stability in extreme environments. Whether in the scorching deserts or icy tundras, these microscopic organisms demonstrate that survival is a matter of preparation, adaptation, and resilience. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, exploring the mechanisms of algal sporulation offers valuable insights into both fundamental biology and applied sciences.

Discovering Plants with Spores: Unveiling Nature's Unique Reproduction Methods

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all algae reproduce by spores. While many algae species, such as certain green algae and red algae, use spores as part of their life cycle, others reproduce through methods like fragmentation, budding, or the release of motile reproductive cells (zoospores).

Spores in algae are specialized cells produced during the reproductive phase of their life cycle. They are often resistant to harsh conditions and can disperse to new environments. Once conditions are favorable, spores germinate and grow into new algal individuals, ensuring survival and propagation of the species.

Algal spores and plant spores share similarities in function, as both are used for reproduction and dispersal. However, they differ in structure and origin. Algal spores are typically produced by unicellular or simple multicellular organisms, while plant spores are part of the life cycle of more complex, multicellular plants like ferns and mosses.

Yes, many algae species have complex life cycles that include both sexual and asexual reproduction involving spores. Asexual spores (e.g., zoospores) are produced through mitosis, while sexual spores (e.g., zygotes) result from the fusion of gametes. This dual reproductive strategy enhances genetic diversity and adaptability.