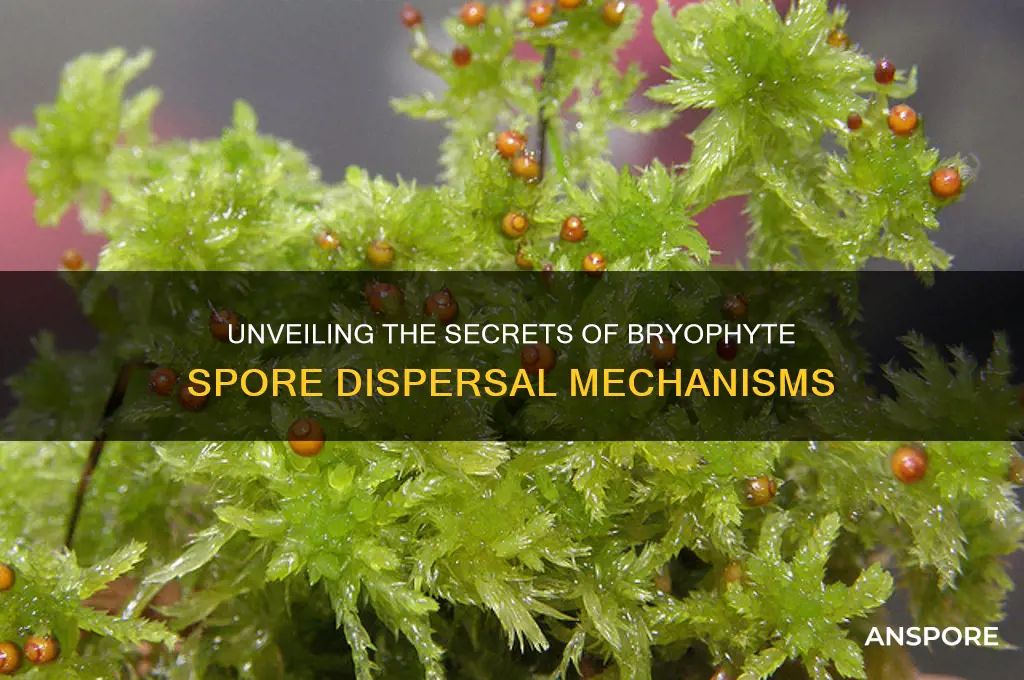

Bryophytes, which include mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, rely on diverse mechanisms for spore dispersal to ensure their survival and propagation. Unlike vascular plants, bryophytes lack true roots, stems, and leaves, and their spores are typically produced in specialized structures called sporangia. Dispersal methods vary widely among species but often involve a combination of abiotic and biotic factors. Abiotic mechanisms include wind, which is a primary disperser due to the lightweight nature of spores, and water, particularly in aquatic or humid environments. Additionally, some bryophytes utilize ballistic mechanisms, where spores are forcibly ejected from the sporangium. Biotic dispersal can occur through animals, such as insects or small mammals, that inadvertently carry spores on their bodies. Environmental factors like humidity, temperature, and substrate type also influence dispersal efficiency. Understanding these dispersal strategies is crucial for studying bryophyte ecology, distribution, and conservation in diverse ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Wind, water, animals, and explosive spore discharge |

| Wind Dispersal | Spores are lightweight and easily carried by air currents |

| Water Dispersal | Spores can be transported by rain splash or flowing water |

| Animal Dispersal | Spores adhere to animal fur or feathers and are carried to new locations |

| Explosive Discharge | Spores are forcibly ejected from capsule-like structures (sporangia) |

| Spore Size | Typically small (5–50 µm) to facilitate dispersal |

| Surface Adaptations | Spores may have hydrophobic or sticky surfaces to aid dispersal |

| Environmental Factors | Humidity, temperature, and substrate type influence dispersal success |

| Distance of Dispersal | Ranges from a few meters (water/animal) to kilometers (wind) |

| Seasonal Patterns | Dispersal often peaks during dry, windy conditions |

| Ecological Significance | Ensures colonization of new habitats and genetic diversity |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Wind dispersal mechanisms

Bryophytes, including mosses and liverworts, have evolved ingenious strategies to disperse their spores over vast distances, and wind plays a pivotal role in this process. Unlike vascular plants, bryophytes lack true roots, stems, and leaves, relying instead on external factors for spore dissemination. Wind dispersal mechanisms in bryophytes are finely tuned to exploit air currents, ensuring that spores reach new habitats efficiently. These mechanisms often involve specialized structures that enhance spore release and transport, maximizing the chances of successful colonization.

One of the most effective wind dispersal mechanisms in bryophytes is the use of sporophytes with elongated seta (stalks). These structures elevate the spore capsules above the ground, positioning them to catch even the slightest breeze. For example, in species like *Sphagnum*, the sporophyte’s capsule dries out and splits open, releasing spores that are carried away by wind. The height of the seta is critical; studies show that spores released from taller seta travel significantly farther, increasing the likelihood of reaching suitable environments. To optimize this mechanism, bryophytes often time spore release to coincide with dry, windy conditions, ensuring maximum dispersal efficiency.

Another innovative wind dispersal strategy is the explosive spore discharge seen in some liverworts. Species like *Marchantia* have capsule structures that build up internal pressure, eventually bursting open and ejecting spores with force. This mechanism propels spores into the air, where they can be caught by wind currents. While this method requires more energy from the plant, it ensures that spores are dispersed even in still air. Researchers estimate that explosive discharge can launch spores up to 15 cm vertically, significantly enhancing their wind capture potential. This technique highlights the balance bryophytes strike between energy investment and dispersal success.

Practical observations reveal that spore size and shape also play a crucial role in wind dispersal. Bryophyte spores are typically small, measuring between 5 to 50 micrometers in diameter, which allows them to remain suspended in air currents for longer periods. Additionally, some spores have wing-like structures or rough surfaces that increase their aerodynamic properties, aiding in wind transport. For instance, spores of *Polytrichum* mosses have a rough outer layer that reduces air resistance, enabling them to travel farther. Gardeners and conservationists can leverage this knowledge by planting bryophytes in open, windy areas to encourage natural dispersal and colonization.

In conclusion, wind dispersal mechanisms in bryophytes are a testament to their adaptability and resourcefulness. From elevated sporophytes to explosive discharge and aerodynamically optimized spores, these strategies ensure that bryophytes can thrive in diverse environments. Understanding these mechanisms not only deepens our appreciation of bryophyte biology but also provides practical insights for conservation and cultivation efforts. By mimicking natural conditions, such as ensuring adequate airflow and timing spore release, we can support the successful dispersal and growth of these remarkable plants.

Does O157:H7 Strain of E. coli Produce Spores? Facts Revealed

You may want to see also

Water transport in aquatic habitats

In aquatic habitats, water serves as both the medium and the mechanism for bryophyte spore dispersal, a process finely tuned by evolutionary adaptations. Unlike terrestrial bryophytes that rely on wind or animals, aquatic species harness water currents to distribute spores over varying distances. For instance, *Fontinalis antipyretica*, a common aquatic moss, releases spores that are carried downstream, colonizing new substrates along riverbeds and lake floors. This passive transport is highly efficient in flowing waters, where currents act as conveyor belts for microscopic spores. However, in stagnant environments, dispersal relies on water turbulence caused by wind or aquatic organisms, highlighting the adaptability of these plants to diverse water conditions.

To maximize dispersal success, aquatic bryophytes often produce spores with specific densities and surface properties. Spores of *Sphagnum* species, for example, are lightweight and hydrophobic, allowing them to float on the water’s surface and travel greater distances. In contrast, heavier spores of submerged liverworts like *Pellia* species sink quickly, ensuring they settle near the parent plant in nutrient-rich sediments. This variation in spore characteristics underscores a strategic trade-off: floating spores increase dispersal range but risk landing in unsuitable habitats, while sinking spores prioritize proximity to known favorable conditions.

Practical observations reveal that water velocity and depth significantly influence dispersal patterns. In fast-moving streams, spores can travel up to 100 meters within minutes, while in shallow ponds, dispersal is limited to a few meters unless disturbed by external factors. For hobbyists cultivating aquatic bryophytes, mimicking natural water flow conditions can enhance spore distribution in aquariums or garden ponds. A simple tip is to use a gentle water pump to create currents, ensuring spores reach desired substrates without being trapped in stagnant zones.

Comparatively, aquatic bryophytes face fewer barriers to dispersal than their terrestrial counterparts, which must contend with physical obstacles like trees or buildings. Water’s fluidity provides a continuous pathway, but it also poses challenges, such as dilution of spore concentration over large areas. This trade-off necessitates high spore production rates, with some species releasing millions of spores per season to compensate for potential losses. Such prolific reproduction ensures that even a small fraction of spores successfully germinate, maintaining population viability.

In conclusion, water transport in aquatic habitats is a dynamic and specialized process that leverages the unique properties of water and spores. By understanding these mechanisms, enthusiasts and researchers can better cultivate and study aquatic bryophytes, appreciating their role in freshwater ecosystems. Whether in a natural stream or a controlled aquarium, the interplay of water currents, spore characteristics, and environmental factors shapes the dispersal and survival of these fascinating plants.

Hydrogen Peroxide's Efficacy Against Clostridium Spores: A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Animal-aided spore dispersal methods

Animals play a surprisingly intimate role in the life cycle of bryophytes, those humble yet resilient mosses and liverworts. While wind and water are often the first dispersal methods that come to mind, animals offer a targeted, efficient, and often accidental service. From the tiniest insects to larger mammals, these creatures become unwitting couriers, carrying spores to new habitats and ensuring the survival and spread of these ancient plants.

Bryophyte spores are microscopic, lightweight, and often equipped with structures like elaters or wings that aid in wind dispersal. However, relying solely on wind is a gamble, especially in dense vegetation or sheltered environments. This is where animals step in, quite literally, as they brush against, ingest, or carry spores on their bodies.

The Hitchhiker's Guide to Spore Dispersal:

Imagine a tiny springtail, no larger than a pinhead, hopping through a mossy patch. As it moves, spores adhere to its body, hitching a ride to a new location. This is external dispersal, a common method employed by various invertebrates. Slugs and snails, with their slimy trails, also act as spore carriers, leaving behind a microscopic trail of potential new growth. Even larger animals, like birds and mammals, can inadvertently transport spores on their feathers, fur, or feet, dispersing them over greater distances.

Think of a bird nesting in a mossy tree, its feathers becoming a mobile spore bank as it flies to different locations.

Internal Journeys: A Digestive Detour:

Some animals take spore dispersal a step further, ingesting them directly. This might seem counterintuitive, but many spores are remarkably resilient and can survive the digestive tract of certain animals. Earthworms, for example, consume organic matter containing spores, which then pass through their digestive system unharmed and are deposited in their castings, ready to germinate in nutrient-rich soil.

Mutual Benefits: A Symbiotic Relationship?

While the primary benefit of animal-aided dispersal lies with the bryophytes, some animals might also gain advantages. For instance, certain insects may find shelter or food within moss cushions, inadvertently aiding in spore dispersal while fulfilling their own needs. This hints at a potential mutualistic relationship, where both parties benefit from the interaction.

Further research is needed to fully understand the complexities of these interactions and the extent to which animals actively contribute to bryophyte success.

Practical Implications:

Understanding animal-aided spore dispersal has practical applications in conservation and restoration efforts. By identifying key animal dispersers in specific habitats, we can develop strategies to promote their presence and activity, thereby enhancing bryophyte diversity and ecosystem health. This could involve creating suitable habitats for disperser species, such as maintaining diverse vegetation structures and minimizing disturbance.

Do Fungi Produce Spores? Unveiling Their Reproduction Secrets

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Explosive capsule discharge techniques

Bryophytes, such as mosses and liverworts, have evolved ingenious mechanisms to disperse their spores, ensuring the survival and spread of their species. Among these, explosive capsule discharge techniques stand out as a fascinating adaptation. This method involves the rapid release of spores from specialized structures, often triggered by environmental cues like changes in humidity or temperature. The force generated can propel spores over significant distances, sometimes up to several meters, maximizing their chances of reaching new habitats.

To understand the mechanics, consider the structure of a bryophyte sporophyte. The capsule, where spores develop, is typically attached to a seta (stalk) and features a lid-like structure called the operculum. As the capsule dries, it undergoes turgor changes, creating internal tension. When conditions are optimal, the operculum suddenly separates, releasing the spores in a burst of energy. This process is akin to a miniature explosion, hence the term "explosive discharge." For example, in the genus *Sphagnum*, the capsule walls twist and contract, acting like a spring to eject spores with remarkable force.

Practical observation of this phenomenon can be enhanced by placing mature bryophyte capsules under a microscope or using high-speed photography to capture the moment of discharge. Researchers have noted that the timing and efficiency of this mechanism are influenced by environmental factors, such as air moisture and light exposure. For instance, spores are more likely to be released during dry, sunny periods when the capsule walls are maximally stressed. This ensures that spores are dispersed under conditions favorable for their survival and germination.

While explosive capsule discharge is highly effective, it is not without limitations. The success of spore dispersal depends on the capsule's orientation and the surrounding microenvironment. Capsules positioned in shaded or obstructed areas may not achieve optimal discharge angles, reducing dispersal range. Additionally, the energy required for this mechanism limits its use to sporophytes with sufficient resources, often those in nutrient-rich habitats. Despite these constraints, the technique remains a testament to the evolutionary ingenuity of bryophytes.

Incorporating this knowledge into conservation efforts or botanical studies can yield practical benefits. For instance, understanding the timing and conditions of spore release can inform the collection of bryophyte samples for research or restoration projects. By mimicking natural triggers, such as controlled drying cycles, scientists can optimize spore harvesting. This approach not only aids in the study of bryophyte ecology but also supports efforts to preserve these vital components of ecosystems worldwide.

Psilocybe Cubensis Spores: Surviving Extreme Cold Conditions Explained

You may want to see also

Human activities impact on dispersal

Human activities have significantly altered the natural dispersal patterns of bryophyte spores, often with unintended consequences. Urbanization, for instance, introduces artificial surfaces like concrete and asphalt, which can act as barriers to spore movement. Unlike natural substrates such as soil or bark, these surfaces lack the moisture retention and texture needed for spores to adhere and germinate. As a result, urban areas may experience reduced bryophyte diversity, particularly in species reliant on wind or water dispersal. A study in *Journal of Bryology* (2018) found that urban green spaces with higher anthropogenic disturbance had 30% fewer bryophyte species compared to undisturbed areas.

Agricultural practices, particularly the use of herbicides and intensive tilling, further disrupt bryophyte spore dispersal. Herbicides like glyphosate, applied at rates of 1–2 liters per hectare, can directly kill bryophytes or reduce the viability of their spores. Tilling, while beneficial for crop growth, destroys the microhabitats bryophytes depend on for colonization. For example, *Sphagnum* mosses, which rely on water dispersal, are particularly vulnerable in drained peatlands converted for agriculture. Farmers can mitigate this by creating buffer zones with undisturbed vegetation, which act as spore reservoirs, and reducing herbicide use near sensitive habitats.

Climate change, driven by human activities, exacerbates these challenges by altering environmental conditions critical for spore dispersal. Rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns can desynchronize the release and landing of spores, reducing germination success. For instance, *Marchantia polymorpha*, a liverwort that disperses spores via splash cups, requires consistent moisture for spore release. Prolonged droughts, increasingly common in regions like the Mediterranean, can render this mechanism ineffective. Conservation efforts should focus on restoring hydrological cycles in affected areas, such as rewetting peatlands or implementing rainwater harvesting systems.

Finally, habitat fragmentation due to infrastructure development isolates bryophyte populations, limiting gene flow and reducing their resilience to environmental changes. Roads, for example, act as physical barriers to spore dispersal, particularly for species with limited dispersal ranges. A comparative study in *Ecology and Evolution* (2020) showed that bryophyte populations near highways had 40% lower genetic diversity compared to those in contiguous forests. To counteract this, ecologists recommend constructing wildlife corridors or "bryophyte bridges" using natural substrates like logs or soil patches to reconnect fragmented habitats.

In summary, human activities disrupt bryophyte spore dispersal through urbanization, agriculture, climate change, and habitat fragmentation. Practical solutions include reducing herbicide use, restoring hydrological cycles, and creating corridors for spore movement. By addressing these specific impacts, we can preserve bryophyte biodiversity and the ecosystem services they provide, such as soil stabilization and carbon sequestration.

Hydra Reproduction: Do They Form Spores or Use Other Methods?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bryophyte spores are often dispersed by wind due to their lightweight nature and the elevated position of the sporophytes. The spores are released from the capsule and carried over long distances by air currents, aiding in colonization of new habitats.

Yes, water is a significant dispersal agent for bryophyte spores, especially in moist environments. Spores can be carried by raindrop splash, flowing water, or even in thin water films, allowing them to reach new locations.

Yes, animals can aid in bryophyte spore dispersal. Small creatures like insects, snails, or mammals may inadvertently carry spores on their bodies as they move through habitats, facilitating their spread.

Some bryophytes, particularly certain liverworts, have sporophytes that dry out and burst open, explosively releasing spores into the air. This mechanism enhances dispersal over short to medium distances.

Human activities such as deforestation, urbanization, and pollution can disrupt natural spore dispersal patterns. However, humans can also aid dispersal unintentionally by transporting spores on clothing, footwear, or vehicles across regions.