Fungi are a diverse group of organisms that play crucial roles in ecosystems, primarily as decomposers and symbionts. One of their most distinctive features is their reproductive strategy, which often involves the production of spores. Spores are microscopic, single-celled or multicellular structures that serve as a means of dispersal and survival in adverse conditions. Unlike plants and animals, fungi do not produce seeds; instead, they rely on spores to propagate and colonize new environments. These spores can be produced through both asexual and sexual reproduction, depending on the fungal species and environmental conditions. Understanding whether and how fungi produce spores is essential for studying their life cycles, ecological roles, and applications in fields such as agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do Fungi Produce Spores? | Yes |

| Types of Spores | Asexual (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) and Sexual (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores) |

| Function of Spores | Reproduction, dispersal, and survival in harsh conditions |

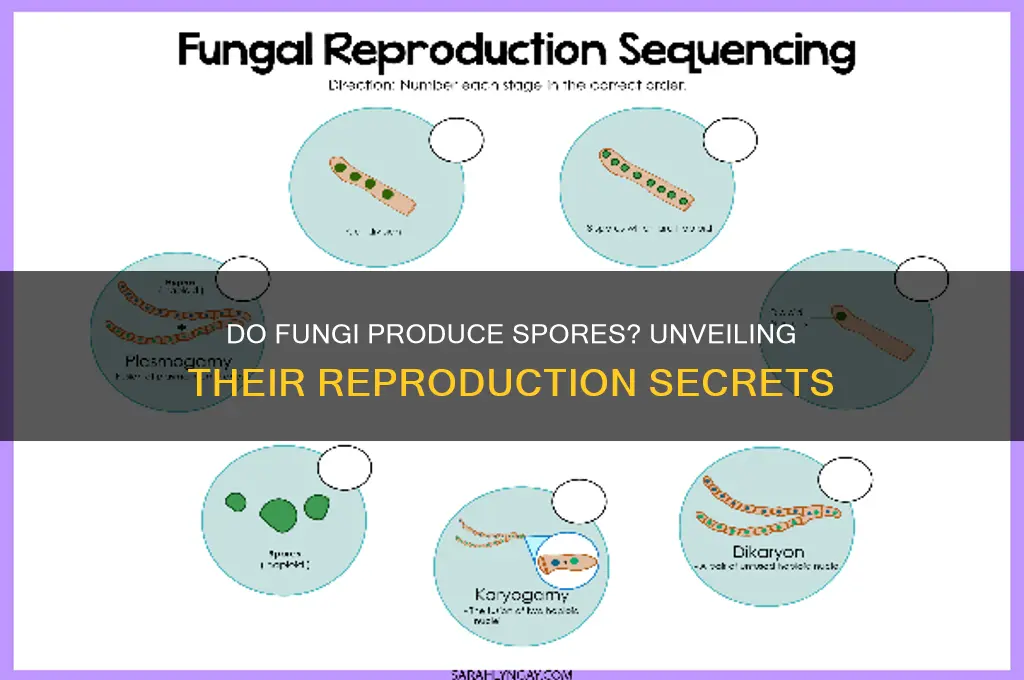

| Sporulation Process | Asexual: via mitosis (e.g., budding, fragmentation); Sexual: via meiosis (e.g., fusion of gametes) |

| Dispersal Methods | Wind, water, animals, or mechanical means (e.g., bursting sporangia) |

| Dormancy | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions return |

| Examples of Spore-Producing Fungi | Molds (e.g., Aspergillus), mushrooms (e.g., Agaricus), yeasts (e.g., Saccharomyces) |

| Ecological Role | Decomposers, symbionts, pathogens; essential in nutrient cycling and ecosystem balance |

| Human Impact | Beneficial (e.g., food, medicine) and detrimental (e.g., crop diseases, allergies) |

| Latest Research | Advances in understanding spore genetics, dispersal mechanisms, and applications in biotechnology |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Types of Spores Produced by Fungi

Fungi are prolific spore producers, and these microscopic structures are fundamental to their life cycles. The diversity of fungal spores is remarkable, each type serving distinct purposes in reproduction, dispersal, and survival. Understanding the various spore types provides insight into the adaptive strategies of fungi, which have enabled their success in nearly every ecosystem on Earth.

Spores as Survival Capsules: A Comparative Analysis

Fungi produce spores tailored to specific environmental challenges. For instance, zygospores, formed by zygomycetes, are thick-walled and resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions like drought or extreme temperatures. In contrast, ascospores, produced by sac fungi (Ascomycota), are often ejected forcibly from ascus sacs, ensuring rapid dispersal. Basidiomycetes, such as mushrooms, produce basidiospores on specialized structures called basidia. These spores are lightweight and easily carried by wind, maximizing their reach. Each spore type reflects the fungus’s ecological niche, whether it thrives in soil, on decaying matter, or as a pathogen.

Practical Applications of Spore Knowledge

Knowing spore types is not just academic—it has practical implications. For example, conidia, asexual spores produced by molds like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, are common allergens and can cause respiratory issues in sensitive individuals. Understanding their dispersal mechanisms helps in designing better ventilation systems or allergen control measures. Similarly, teliospores, produced by rust fungi, are critical in agricultural pest management, as they overwinter and initiate infections in crops. Farmers can use this knowledge to time fungicide applications effectively, reducing crop losses.

The Role of Spores in Fungal Reproduction

Spores are the primary means of fungal reproduction, but their methods vary. Oospores, produced by oomycetes (water molds), are zygotic spores formed through sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic diversity. In contrast, sporangiospores, produced by molds like *Rhizopus*, are asexual and allow rapid colonization of new substrates. This dual reproductive strategy—sexual for diversity and asexual for speed—highlights fungi’s adaptability. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, recognizing spore types can improve yield; for instance, using basidiospore syringes for inoculation ensures consistent growth in mycelium cultures.

Environmental Impact and Human Interaction

Fungal spores play a dual role in ecosystems and human activities. Chlamydospores, thick-walled resting spores produced by fungi like *Candida* and *Fusarium*, can survive in soil for years, posing risks to plant health and food safety. However, spores also have benefits; mycorrhizal fungi, which produce vesicular-arbuscular spores, enhance nutrient uptake in plants, improving soil fertility. For gardeners, incorporating mycorrhizal inoculants can boost plant growth, especially in nutrient-poor soils. Understanding spore types allows for informed decisions, whether mitigating fungal threats or harnessing their benefits.

In summary, the types of spores produced by fungi are as varied as their functions, each adapted to specific ecological roles. From survival to reproduction, these microscopic structures underpin fungal success and influence human activities, from agriculture to health. Recognizing their differences empowers us to coexist with fungi more effectively, whether as adversaries or allies.

Are Mold Spores Alive? Unveiling the Truth About Fungal Life

You may want to see also

Methods of Fungal Spore Dispersal

Fungi are prolific spore producers, releasing trillions into the environment daily. These microscopic units are essential for fungal survival, serving as both reproductive agents and dispersal mechanisms. Understanding how these spores travel reveals the ingenuity of fungal adaptation.

Wind: The Invisible Highway

The most common method of fungal spore dispersal is wind. Fungi like puffballs and certain molds have evolved lightweight, aerodynamic spores that can be carried over vast distances. A single puffball, for instance, can release billions of spores in a single discharge, relying on air currents to scatter them far and wide. This strategy ensures colonization of new habitats, even across continents. However, wind dispersal is unpredictable, and many spores may land in unsuitable environments.

Water: A Liquid Highway for Aquatic Fungi

Aquatic fungi, such as those found in rivers and lakes, utilize water as their primary dispersal medium. Spores released into the water column are carried downstream, eventually settling on submerged surfaces or reaching new aquatic ecosystems. This method is particularly effective for fungi that thrive in moist environments, as water provides both transport and a suitable landing site. For example, the water mold *Saprolegnia* disperses its spores through water, often infecting fish and other aquatic organisms.

Animals: Unwitting Couriers

Fungi have also evolved to exploit animals as dispersal agents. Spores can attach to the fur, feathers, or skin of passing creatures, hitching a ride to new locations. Some fungi, like the bird's nest fungus, produce spore-filled "eggs" that are inadvertently carried away by insects. Others, such as certain species of slime molds, produce sticky spores that adhere to the legs of insects, ensuring widespread distribution. This symbiotic relationship benefits the fungus by expanding its range while often providing no harm or even a food source for the animal.

Explosive Mechanisms: Nature's Fireworks

Some fungi employ more dramatic methods of spore dispersal. The aptly named "gunpowder fungus" (*Peziza*) uses a spring-loaded mechanism to eject spores at high speeds, propelling them several centimeters into the air. Similarly, the "earthstar" fungus (*Geastrum*) opens its star-shaped body, exposing spore sacs that are then dispersed by raindrop impact. These explosive methods ensure rapid and efficient spore release, increasing the likelihood of successful colonization. While less common than wind or water dispersal, these mechanisms highlight the diversity of fungal strategies.

Human Activity: An Unintended Ally

In modern times, human activities have become a significant factor in fungal spore dispersal. Agriculture, forestry, and global trade inadvertently transport spores across continents, introducing fungi to new ecosystems. For example, the movement of soil, plants, and wood products can carry fungal pathogens, leading to outbreaks in previously unaffected areas. Understanding this human-mediated dispersal is crucial for managing fungal diseases in agriculture and natural ecosystems. By recognizing our role in spore dispersal, we can implement measures to mitigate the spread of harmful fungi while appreciating the resilience and adaptability of these organisms.

Mastering Zetsubou Spore: Sliding Under the Plane Explained

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers for Spore Production

Fungi are master responders to their environment, and spore production is no exception. This asexual reproductive strategy is not a constant process but a carefully timed response to specific cues. Understanding these environmental triggers is crucial for fields like agriculture, where managing fungal pathogens relies on predicting spore release, and mycology, where cultivating specific fungi requires mimicking their natural conditions.

Fungal spore production is a complex dance with the environment, choreographed by a multitude of factors. Light, a fundamental environmental cue, plays a pivotal role. Many fungi exhibit photoperiodism, where spore production is synchronized with specific light-dark cycles. For instance, certain molds like *Penicillium* species are known to sporulate more prolifically under continuous light, while others, like some *Aspergillus* strains, prefer alternating light and dark periods. This sensitivity to light quality and duration allows fungi to time their spore release for optimal dispersal and germination conditions.

Moisture, another critical factor, acts as both a trigger and a medium for spore development. While excessive moisture can lead to fungal growth, a specific humidity threshold often initiates sporulation. For example, the common bread mold *Rhizopus stolonifer* requires high humidity (around 90-95%) for optimal spore production. Conversely, some fungi, like certain species of *Trichoderma*, are triggered to sporulate when moisture levels decrease, a strategy that ensures spore dispersal during drier conditions when competition for resources might be lower.

Understanding these environmental triggers allows for targeted interventions. In agricultural settings, manipulating light exposure and humidity levels can disrupt the sporulation cycles of pathogenic fungi, reducing disease spread. Conversely, in controlled environments like laboratories or mushroom farms, mimicking these natural cues can optimize spore production for research or cultivation purposes.

Temperature acts as a fine-tuning mechanism, influencing the timing and intensity of spore production. Most fungi have an optimal temperature range for sporulation, often correlating with their ecological niche. For example, thermophilic fungi like *Thermomyces lanuginosus* sporulate best at temperatures exceeding 50°C, while mesophilic fungi like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker's yeast) prefer temperatures around 25-30°C. Deviations from these optimal ranges can either delay or inhibit sporulation altogether.

Nutrient availability also plays a crucial role. While fungi can sporulate under nutrient-limited conditions, the presence of specific nutrients can significantly enhance spore production. For instance, nitrogen-rich environments often stimulate sporulation in many fungal species. Conversely, nutrient depletion can trigger sporulation as a survival mechanism, allowing fungi to disperse and seek new resources.

By deciphering the language of environmental cues, we gain a powerful tool for managing fungal populations. From controlling plant diseases to cultivating beneficial fungi, understanding the intricate relationship between environment and spore production opens doors to innovative solutions in agriculture, biotechnology, and beyond.

Freezing Athlete's Foot Spores: Effective Treatment or Myth?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of Spores in Fungal Reproduction

Fungi are masters of survival, and their reproductive strategy revolves around spores—tiny, resilient structures designed to disperse and endure. Unlike seeds in plants, fungal spores are unicellular or multicellular units capable of developing into new individuals under favorable conditions. This adaptability allows fungi to colonize diverse environments, from forest floors to human habitats, ensuring their persistence across generations.

Consider the lifecycle of *Aspergillus*, a common mold. When conditions are optimal, it produces spores in structures called conidiophores. These spores are lightweight and easily airborne, allowing them to travel vast distances. Upon landing in a suitable environment—say, a damp wall—they germinate, forming hyphae that penetrate the substrate and establish a new colony. This process highlights the spore’s dual role: as a dispersal agent and a survival mechanism during harsh conditions.

Spores are not just passive carriers of genetic material; they are engineered for longevity. Some fungal spores, like those of *Cladosporium*, can remain dormant for years, withstanding extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation. This resilience is achieved through thick cell walls composed of chitin and melanin, which protect the spore’s internal structures. For instance, *Cryptococcus neoformans* spores are known to survive in bird droppings, a trait that aids their transmission to new hosts.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore behavior is crucial for managing fungal infections and infestations. For example, in healthcare settings, *Aspergillus* spores pose a risk to immunocompromised patients. HEPA filters and regular cleaning protocols are employed to reduce spore counts in the air. Similarly, in agriculture, controlling spore dispersal of pathogens like *Botrytis cinerea* involves adjusting humidity levels and applying fungicides at critical stages of crop growth.

In conclusion, spores are the cornerstone of fungal reproduction, combining dispersal efficiency with remarkable durability. Their ability to adapt to diverse conditions ensures fungi’s ecological dominance. Whether in natural ecosystems or human environments, managing spore behavior requires targeted strategies informed by their unique biology. By studying spores, we gain insights into fungal resilience and develop effective methods to harness or control their impact.

Organo Gold Spores: A Natural Remedy to Lower Blood Sugar?

You may want to see also

Comparing Fungal Spores to Plant Seeds

Fungi and plants both rely on reproductive structures to ensure their survival and propagation, yet their methods differ significantly. While plants produce seeds, fungi generate spores, each adapted to their respective environments and life cycles. This comparison highlights the unique strategies these organisms employ to thrive in diverse ecosystems.

Analytical Perspective:

Fungal spores and plant seeds serve analogous purposes but exhibit distinct characteristics. Spores are typically unicellular and lightweight, designed for wind or water dispersal, enabling fungi to colonize new habitats rapidly. In contrast, seeds are multicellular, encased in protective coats, and often require specific conditions (e.g., soil, moisture) to germinate. For instance, a single mushroom can release millions of spores in a day, whereas a tree might produce thousands of seeds annually. This disparity underscores the efficiency of spores in maximizing dispersal versus the seeds' focus on survival and establishment.

Instructive Approach:

To understand their differences, consider their roles in reproduction. Fungal spores are akin to microscopic survival pods, capable of lying dormant for years until conditions are favorable. They can be as small as 10 micrometers, allowing them to travel vast distances. Plant seeds, however, are larger and more resource-intensive, often relying on animals or wind for dispersal. For gardeners, this means fungal spores can quickly invade new areas, while seeds require careful planting and nurturing. To control fungal growth, maintain dry conditions, as spores thrive in moisture. For seeds, ensure proper soil depth and sunlight for successful germination.

Comparative Insight:

While both spores and seeds are reproductive units, their structures and functions diverge. Spores are often haploid, produced via asexual or sexual reproduction, and can germinate directly into new fungal structures. Seeds, on the other hand, are diploid, formed from the fusion of gametes, and develop into embryos surrounded by nutrient-rich endosperm. This comparison reveals how fungi prioritize quantity and adaptability, whereas plants invest in quality and resilience. For example, a spore can grow into a new fungus within days, while a seed may take weeks or months to sprout, depending on the species.

Descriptive Takeaway:

Imagine a forest floor: fungal spores drift invisibly through the air, settling on decaying logs and soil, quickly forming mycelium networks. Nearby, a tree scatters its seeds, each a miniature package of life, waiting for the right moment to take root. This juxtaposition illustrates the elegance of nature's design. Spores embody efficiency and ubiquity, while seeds symbolize potential and longevity. Both are essential to their ecosystems, yet their strategies reflect the contrasting worlds of fungi and plants. By studying these differences, we gain insight into the intricate balance of life on Earth.

Fossilized Spores: Unlocking the Mystery of Regeneration Potential

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all fungi produce spores. While most fungi reproduce via spores, some fungi, like certain yeasts, primarily reproduce through budding or fission.

Fungi produce spores through specialized structures like sporangia, basidia, or asci, depending on the fungal group. Spores are formed via meiosis or mitosis and are released into the environment for dispersal.

Fungal spores serve as a means of reproduction and dispersal. They allow fungi to survive harsh conditions, spread to new environments, and colonize new substrates.

Some fungal spores can be harmful to humans, especially to those with weakened immune systems or respiratory conditions. Inhalation of certain spores, like those from *Aspergillus* or *Histoplasma*, can cause infections or allergies.

Fungal spores are highly resilient and can survive for extended periods, ranging from months to years, depending on environmental conditions such as temperature, humidity, and substrate availability.