Fungi are classified based on a variety of characteristics, including their spore-producing structures, which play a crucial role in their reproduction and identification. Spores, the primary means of fungal dispersal and survival, are produced in specialized structures such as sporangia, asci, or basidia, depending on the fungal group. The classification of fungi into major divisions, such as Zygomycota, Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and others, relies heavily on the type, arrangement, and development of these spore-bearing structures. For instance, Ascomycetes produce spores within sac-like asci, while Basidiomycetes form spores on club-shaped basidia. Additionally, factors like spore color, shape, and wall structure further aid in taxonomic categorization. Understanding how fungi are classified through their spores not only highlights their evolutionary relationships but also provides insights into their ecological roles and practical applications.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Type | Fungi are classified based on the type of spores they produce, including asexual spores (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) and sexual spores (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores). |

| Asexual Spores | Produced via mitosis; examples include conidia (e.g., in Aspergillus), sporangiospores (e.g., in Zygomycota), and arthrospores (e.g., in Schizosaccharomyces). |

| Sexual Spores | Produced via meiosis; examples include zygospores (e.g., in Zygomycota), ascospores (e.g., in Ascomycota), and basidiospores (e.g., in Basidiomycota). |

| Spore Morphology | Shape, size, color, and wall structure (e.g., smooth, ornamented) are key characteristics used for classification. |

| Spore Dispersal | Methods include wind, water, animals, or explosive discharge (e.g., in puffballs). |

| Spore Formation Structures | Spores are produced in specific structures like conidiophores, sporangia, asci, or basidia, which are taxonomically significant. |

| Genetic Basis | Modern classification combines spore characteristics with molecular data (e.g., DNA sequencing) for accurate taxonomy. |

| Ecological Role | Spore characteristics often correlate with ecological niches, such as saprotrophic, parasitic, or symbiotic lifestyles. |

| Kingdom Classification | Fungi are primarily classified into phyla based on spore types: Chytridiomycota (zoospores), Zygomycota (zygospores), Ascomycota (ascospores), and Basidiomycota (basidiospores). |

| Reproductive Strategies | Classification reflects reproductive modes: asexual reproduction (e.g., conidia) vs. sexual reproduction (e.g., ascospores, basidiospores). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore morphology: Shape, size, color, and structure of spores used for fungal classification

- Spore dispersal methods: Mechanisms like wind, water, or animals for spore distribution

- Sporulation types: Classification based on spore-bearing structures (e.g., asci, basidia)

- Sexual vs. asexual spores: Differentiation between meiospores and mitospores in fungal taxonomy

- Spore wall composition: Chemical and physical properties aiding in fungal identification

Spore morphology: Shape, size, color, and structure of spores used for fungal classification

Fungal spores are remarkably diverse in shape, a critical trait for classification. From the smooth, spherical spores of *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast) to the elongated, cylindrical spores of *Aspergillus* species, morphology provides a visual fingerprint. For instance, *Rust fungi* produce dicotyledonous spores with intricate, thorn-like projections, while *Smut fungi* generate thick-walled, darkly pigmented spores. Observing these shapes under a microscope at 400x–1000x magnification allows mycologists to differentiate species with precision. A single spore’s silhouette can reveal its genus, ecological role, and even its pathogenic potential.

Size matters in spore classification, often correlating with dispersal mechanisms and habitat adaptation. Spores range from 1–100 micrometers, with *Cryptococcus neoformans* producing unusually large (5–10 μm) capsules, aiding in immune evasion. In contrast, *Fusarium* species generate smaller (3–5 μm) spores, optimized for wind dispersal. Measuring spore size requires calibrated micrometers or software like ImageJ, ensuring accuracy within 0.1 μm. Larger spores tend to settle quickly, favoring soil-dwelling fungi, while smaller spores remain airborne, suiting plant pathogens. This size-function relationship is a cornerstone of ecological classification.

Color is not merely aesthetic; it serves diagnostic purposes. Spores of *Penicillium* are blue-green due to penicillin production, while *Alternaria* spores appear dark brown from melanin. Pigmentation often indicates UV resistance or spore maturity. For example, immature *Ustilago* spores are pale, darkening as they mature. Color analysis uses spectrophotometry or simple color charts under standardized lighting. However, caution is advised: environmental factors like humidity can alter spore hue, necessitating controlled conditions for accurate identification.

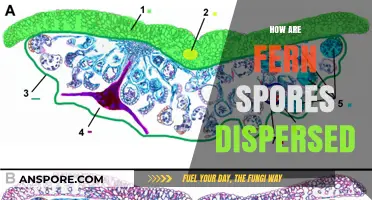

Spore structure—wall thickness, septation, and ornamentation—is a taxonomic goldmine. *Zygomycota* spores lack septa, while *Ascomycetes* often feature multicellular, septate spores. Ornamentation, such as the echinulated (spiny) spores of *Cladosporium*, aids in adhesion and protection. Structural analysis employs scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to reveal details invisible to light microscopes. For instance, *Basidiomycota* spores have a distinctive germ pore, a critical identifier. Understanding these structural nuances requires training but rewards with unparalleled taxonomic clarity.

Practical tips for spore morphology analysis include using lactophenol cotton blue stain to highlight cell walls and maintaining a spore atlas for reference. Always document observations with high-resolution imaging and note environmental conditions, as these influence spore characteristics. While morphology is powerful, it should complement molecular methods like DNA sequencing for robust classification. Mastery of spore morphology transforms a microscope into a key to the fungal kingdom.

Can You See Truffle Spores? Unveiling the Mystery of Fungal Reproduction

You may want to see also

Spore dispersal methods: Mechanisms like wind, water, or animals for spore distribution

Fungi have evolved diverse strategies to disperse their spores, ensuring survival and propagation across varied environments. Among the most common mechanisms are wind, water, and animal-mediated dispersal, each tailored to specific fungal species and ecological niches. Wind dispersal, for instance, is highly effective for lightweight spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, which can travel vast distances in air currents. These spores are often produced in large quantities to increase the likelihood of reaching suitable substrates. In contrast, water dispersal is favored by aquatic or semi-aquatic fungi like *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis*, the chytrid fungus responsible for amphibian declines. Their spores are released into water bodies, where currents carry them to new hosts or habitats. Animal-mediated dispersal, seen in species like *Cordyceps*, relies on insects or other organisms to transport spores, often after the fungus has manipulated the host’s behavior. This method ensures targeted delivery to specific environments, enhancing colonization success.

Analyzing these mechanisms reveals their adaptability to fungal lifestyles. Wind dispersal is ideal for saprotrophic fungi that decompose organic matter across wide areas, while water dispersal suits fungi dependent on aquatic ecosystems. Animal-mediated dispersal is particularly strategic for parasitic or entomopathogenic fungi, which require direct contact with hosts. For example, *Cordyceps* spores attach to ants or other insects, eventually infecting and manipulating them to release spores in optimal locations. This precision contrasts with the scattergun approach of wind dispersal, highlighting how fungi optimize energy expenditure based on their ecological roles. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on fungal biology but also informs efforts to control pathogenic species or harness beneficial fungi in agriculture and medicine.

To observe spore dispersal in action, consider a simple experiment: place a moldy piece of bread in a sealed container with a damp cotton ball to maintain humidity. Over days, note the spread of fungal colonies, which often indicates wind-like dispersal within the confined space. For water dispersal, submerge a spore-bearing fungal sample in a container of water and observe how currents distribute spores. Animal-mediated dispersal can be simulated by introducing insects to spore-covered surfaces and tracking their movement. These experiments underscore the efficiency of each mechanism and its relevance to fungal survival. Practical tips include using a magnifying glass to observe spores and maintaining sterile conditions to avoid contamination.

Comparatively, wind dispersal is the most widespread but least targeted, while water and animal-mediated methods offer greater precision at the cost of limited range. Wind-dispersed spores, such as those of *Fusarium*, often have aerodynamic shapes or are produced in dry, lightweight structures like conidia. Water-dispersed spores, like those of *Blastocladiella*, are typically denser and may have sticky coatings to adhere to surfaces. Animal-mediated spores, such as those of *Ophiocordyceps*, are often durable and equipped with hooks or adhesives to attach to hosts. These adaptations reflect the trade-offs fungi make between dispersal range and accuracy, depending on their reproductive strategies.

In conclusion, spore dispersal methods are a testament to fungal ingenuity, each mechanism finely tuned to the species’ ecological needs. Wind dispersal maximizes reach, water dispersal leverages fluid dynamics, and animal-mediated dispersal ensures targeted delivery. By studying these processes, we gain insights into fungal ecology and potential applications, from biocontrol agents to models for drug delivery systems. Whether through experiments or field observations, exploring these mechanisms offers a deeper appreciation of fungi’s role in ecosystems and their impact on human endeavors.

Can Moss Spores Make You Sick? Uncovering Potential Health Risks

You may want to see also

Sporulation types: Classification based on spore-bearing structures (e.g., asci, basidia)

Fungi reproduce through spores, and the structures that bear these spores are key to their classification. These spore-bearing structures, such as asci and basidia, are not merely reproductive tools but also diagnostic features that mycologists use to categorize fungi into distinct groups. Understanding these structures provides a window into the evolutionary relationships and ecological roles of different fungal species.

Consider the asci, sac-like structures found in the Ascomycota phylum, often referred to as sac fungi. Each ascus typically contains eight spores, called ascospores, which are formed through a process called ascogenesis. For example, the yeast *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* produces asci during its sexual reproduction phase. These structures are not just microscopic curiosities; they are critical in industries like baking and brewing, where the controlled sporulation of yeast ensures consistent fermentation. To observe asci, a simple wet mount under a 40x microscope objective can reveal their distinctive shape and spore arrangement, offering a practical way to identify Ascomycota species in a laboratory setting.

In contrast, basidia are club-shaped structures characteristic of the Basidiomycota phylum, which includes mushrooms, puffballs, and rusts. Each basidium typically bears four spores, called basidiospores, attached to sterigmata. The mushroom *Agaricus bisporus* (the common button mushroom) is a prime example of a basidiomycete. Unlike asci, basidia often require more advanced staining techniques, such as cotton blue or methyl blue, to clearly visualize the spores and sterigmata under a microscope. This distinction in spore-bearing structures highlights the diversity within fungal reproduction strategies and underscores the importance of structural analysis in classification.

A comparative analysis of asci and basidia reveals not only their morphological differences but also their ecological implications. Ascomycota fungi, with their asci, are often pioneers in nutrient-poor environments, breaking down complex organic matter. Basidiomycota, on the other hand, are typically wood decomposers and mycorrhizal symbionts, playing a crucial role in forest ecosystems. For instance, the basidiomycete *Laccaria bicolor* forms mutualistic relationships with tree roots, enhancing nutrient uptake. Recognizing these spore-bearing structures allows ecologists to predict fungal functions in their habitats, guiding conservation and agricultural practices.

To classify fungi based on spore-bearing structures, follow these steps: first, prepare a spore mount using a sterile blade to collect fungal tissue and a drop of water or mounting medium on a microscope slide. Second, examine the slide under a compound microscope, noting the presence of asci, basidia, or other structures. Third, consult a mycological key or database to match your observations with known species. Caution: avoid inhaling spore-laden air during collection, as some fungal spores can cause allergies or respiratory issues. By mastering this technique, you can contribute to the accurate identification and classification of fungi, bridging the gap between laboratory observation and field application.

Why Cheats Don't Work in Spore on Steam: Troubleshooting Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sexual vs. asexual spores: Differentiation between meiospores and mitospores in fungal taxonomy

Fungal classification hinges on spore production, a fundamental process that reveals reproductive strategies and evolutionary relationships. At the core of this system lies the distinction between meiospores and mitospores, products of sexual and asexual reproduction, respectively. Meiospores, such as ascospores and basidiospores, arise from meiosis, a genetic recombination process that generates diversity. Mitospores, including conidia and sporangiospores, result from mitosis, a cell division method that produces genetically identical offspring. This differentiation is critical for taxonomists, as it reflects not only reproductive mechanisms but also ecological adaptations and phylogenetic placement.

Consider the lifecycle of *Aspergillus*, a ubiquitous mold. Under favorable conditions, it produces conidia (mitospores) rapidly, allowing for quick colonization of new substrates. However, when stressed or in the presence of a compatible mate, it shifts to sexual reproduction, forming ascospores (meiospores) within a specialized structure called an ascocarp. This dual strategy highlights the adaptive advantage of both systems: asexual spores for efficiency and sexual spores for resilience and genetic innovation. For mycologists, identifying these spore types is essential for accurate classification and understanding fungal ecology.

To differentiate between meiospores and mitospores, examine their origin and structure. Meiospores are typically produced in multicellular fruiting bodies (e.g., asci or basidia) and exhibit complex morphologies, such as septation or appendages. Mitospores, in contrast, are often unicellular, dry, and produced singly or in chains. For instance, the conidia of *Penicillium* are smooth, green, and borne on specialized stalks, while the ascospores of *Saccharomyces* are round and encased in asci. Laboratory techniques, such as staining and microscopy, can further aid identification, with meiospores often showing genetic markers of recombination.

A practical tip for field mycologists: observe the environmental context. Mitospores dominate in stable, nutrient-rich environments, where rapid proliferation is advantageous. Meiospores are more common in fluctuating or stressful conditions, where genetic diversity enhances survival. For example, *Fusarium* species produce abundant macroconidia (mitospores) in soil but form microconidia and chlamydospores (survival structures) under drought. This ecological insight complements morphological analysis, providing a holistic view of fungal taxonomy.

In conclusion, the distinction between meiospores and mitospores is not merely academic—it shapes our understanding of fungal diversity and function. By recognizing their unique roles, taxonomists can unravel evolutionary histories and predict ecological behaviors. Whether studying plant pathogens, decomposers, or symbionts, this knowledge is indispensable. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, mastering this differentiation opens doors to deeper exploration of the fungal kingdom.

Can Mitosis Produce Spores? Unraveling the Role of Cell Division

You may want to see also

Spore wall composition: Chemical and physical properties aiding in fungal identification

The spore wall, a critical structure in fungal biology, is not merely a protective barrier but a treasure trove of taxonomic information. Its composition, a complex blend of chemicals and physical attributes, offers a unique fingerprint for identifying fungal species. This intricate layer, often just nanometers thick, is a testament to the diversity and adaptability of fungi, with its makeup varying significantly across different taxa.

Chemical Complexity Unveiled: The chemical composition of spore walls is a fascinating aspect of fungal biology. Primarily composed of polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids, these components are not randomly arranged. For instance, the inner layer of many fungal spores contains chitin, a polysaccharide also found in insect exoskeletons, providing structural integrity. The outer layer, however, may feature melanins, which offer protection against UV radiation and extreme temperatures. This dual-layer system is not universal; some fungi, like the *Aspergillus* species, have additional layers with unique chemical signatures, such as the presence of galactomannan, a polysaccharide with immunomodulatory properties. These chemical variations are not just structural adaptations but also serve as diagnostic markers for species identification.

Physical Attributes as Taxonomic Tools: Beyond chemistry, the physical properties of spore walls are equally informative. The wall's thickness, for example, varies widely, from the thin-walled spores of *Saccharomyces* yeasts to the robust, multi-layered walls of *Neurospora* spores. This variation is not arbitrary; it often correlates with the fungus's ecological niche and life cycle. Thick-walled spores may indicate a need for long-term survival in harsh environments, while thin walls could suggest rapid germination in favorable conditions. Additionally, the wall's surface texture, observed under electron microscopy, reveals patterns unique to specific fungal groups. These physical characteristics, when combined with chemical analysis, provide a comprehensive profile for accurate fungal classification.

Practical Applications in Identification: In the laboratory, techniques like Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy are employed to analyze spore wall composition. These methods can identify functional groups and molecular bonds, offering a non-destructive way to study spores. For instance, FTIR can detect the presence of specific polysaccharides, while Raman spectroscopy is sensitive to the vibrational modes of molecules, providing information about lipid content. By comparing these spectral signatures to known databases, mycologists can rapidly identify fungal species, even from limited spore samples. This is particularly useful in clinical settings, where quick identification of pathogenic fungi is crucial for effective treatment.

A Comparative Approach to Classification: The study of spore wall composition allows for a comparative analysis of fungal diversity. By examining the walls of closely related species, mycologists can identify subtle differences that have significant taxonomic implications. For example, within the genus *Penicillium*, species like *P. chrysogenum* and *P. camemberti* have distinct spore wall compositions, reflecting their different ecological roles and geographic distributions. This comparative approach not only aids in identification but also provides insights into fungal evolution and adaptation. As more species are analyzed, patterns emerge, allowing for the development of predictive models that can assist in the classification of newly discovered fungi.

In the realm of fungal identification, the spore wall is a microscopic marvel, offering a wealth of information through its chemical and physical properties. Its study is not just an academic exercise but a practical tool with real-world applications, from taxonomy to medicine. As analytical techniques advance, our ability to decipher the secrets of spore walls will only improve, further enhancing our understanding of the fungal kingdom.

Preventing Contamination: Do Spores Compromise Mushroom Grow Room Success?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungi are classified based on spore characteristics such as structure, color, shape, and method of dispersal. Key classifications include Zygomycota (zygospores), Ascomycota (ascospores), Basidiomycota (basidiospores), and Deuteromycota (conidia or other spores).

Spores are critical in fungal classification as they are reproductive structures that define taxonomic groups. Their morphology, production method, and life cycle stage help distinguish between fungal phyla, classes, and species.

No, fungal spores vary widely. For example, ascospores are produced in sac-like structures (asci), basidiospores form on club-shaped structures (basidia), and conidia are asexual spores. These differences are fundamental in classifying fungi into distinct groups.