Ferns, ancient and diverse plants, reproduce not through seeds but via spores, which are microscopic, single-celled structures produced in structures called sporangia on the undersides of their fronds. The dispersal of these spores is a fascinating and critical process for the survival and propagation of fern species. Unlike seeds, which are often dispersed by animals or wind, fern spores rely primarily on wind currents for dispersal due to their lightweight nature. Additionally, some ferns have evolved mechanisms to enhance dispersal, such as the spring-like indusia that catapult spores or the positioning of sporangia on the fronds to maximize exposure to air currents. Understanding how fern spores are dispersed provides insights into their ecological success and adaptability across diverse environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Wind, Water, Animals, and Explosive Sporangia |

| Wind Dispersal | Spores are lightweight and can travel long distances via air currents. |

| Water Dispersal | Spores can be carried by rain splashes or flowing water in aquatic environments. |

| Animal Dispersal | Spores may adhere to animal fur or feathers and be transported to new locations. |

| Explosive Sporangia | Some ferns have sporangia that burst open, propelling spores into the air. |

| Spore Size | Typically small (20–50 µm) to facilitate dispersal by wind. |

| Spore Shape | Often spherical or elliptical to optimize aerodynamic dispersal. |

| Surface Features | Spores may have wings, hairs, or other structures to aid in wind dispersal. |

| Seasonal Timing | Spores are usually released during dry, windy conditions for maximum dispersal. |

| Distance Traveled | Can range from a few meters to several kilometers depending on wind conditions. |

| Environmental Factors | Humidity, temperature, and wind speed influence dispersal efficiency. |

| Adaptations for Dispersal | Thin spore walls, hydrophobic surfaces, and lightweight structures. |

| Role of Indusia | Some ferns have indusia (protective coverings) that open to release spores effectively. |

| Human Impact | Deforestation and habitat fragmentation can reduce spore dispersal ranges. |

| Ecological Significance | Essential for fern colonization, genetic diversity, and ecosystem dynamics. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Wind dispersal mechanisms

Fern spores are remarkably lightweight, often measuring just 30 to 50 micrometers in diameter—smaller than a grain of salt. This minuscule size is no accident; it’s a key adaptation for wind dispersal. When released from the undersides of fern leaves, these spores can be carried aloft by the slightest breeze, traveling distances far beyond their parent plant. This mechanism ensures ferns colonize new habitats efficiently, even in dense forests where sunlight is scarce.

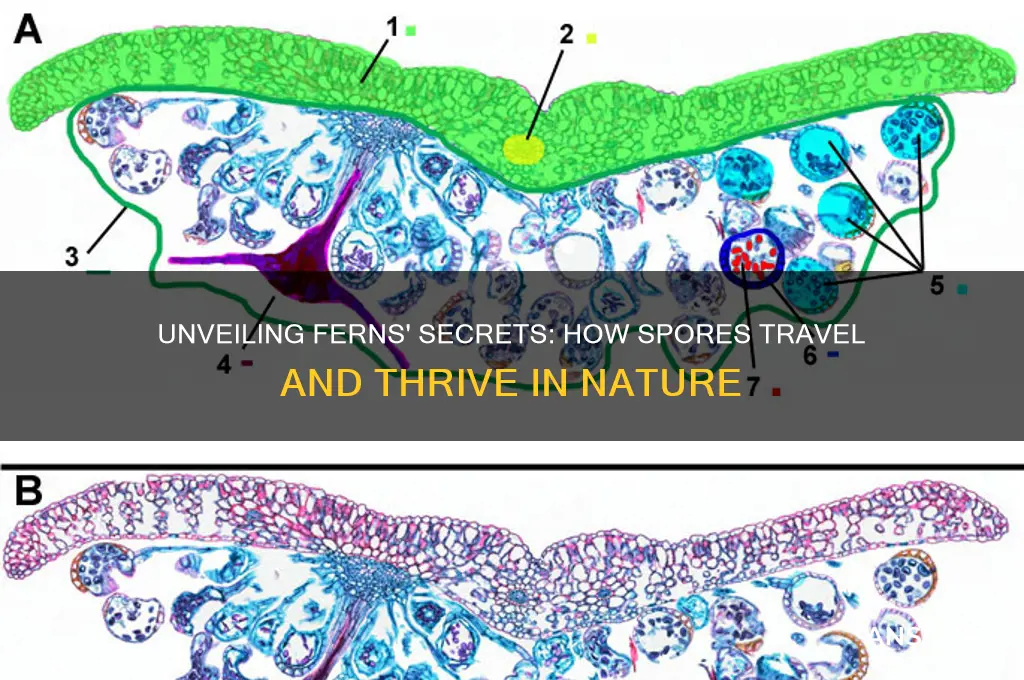

Consider the structure of a fern's sporangium, the sac-like structure where spores develop. Located on the underside of fronds, these sporangia are often clustered into sori, which resemble tiny dots or lines. When mature, the sporangia dry out and contract, creating tension that propels spores into the air. This natural "spring-loading" system maximizes dispersal efficiency, as spores are ejected in a cloud rather than released singly. For gardeners or enthusiasts cultivating ferns, ensuring good air circulation around plants can mimic this natural process, aiding spore release.

Wind dispersal isn’t just about size or ejection force; it’s also about timing. Many fern species release spores during dry, windy periods to capitalize on air currents. For instance, the *Pteris* genus often sheds spores in late summer or early fall, aligning with seasonal winds. This synchronization increases the likelihood of spores reaching suitable environments, such as moist, shaded areas where ferns thrive. If you’re collecting spores for propagation, monitor weather conditions and gather them on dry, breezy days for optimal results.

A comparative look at wind-dispersed plants reveals ferns’ unique strategy. Unlike dandelions, which use feathery pappus to stay airborne, or maple trees, which rely on winged seeds, ferns depend solely on spore mass and ejection mechanics. This simplicity is both a strength and a limitation. While it allows ferns to disperse widely with minimal energy investment, it also makes them reliant on external conditions like wind speed and direction. In urban or indoor settings, a small fan placed near potted ferns can simulate wind, encouraging spore dispersal and potentially increasing the chances of successful colonization.

Finally, the success of wind dispersal lies in numbers. A single fern can produce millions of spores annually, compensating for the low probability of any individual spore finding ideal conditions. This strategy mirrors the "lottery ticket" approach seen in other plant species, where sheer volume outweighs precision. For conservationists or hobbyists, understanding this principle underscores the importance of protecting diverse habitats. Even if most spores fail to germinate, the few that succeed can establish new fern populations, ensuring the species’ survival in changing environments.

Toxin Damage vs. Procs: What Really Pops Spores?

You may want to see also

Water transport in aquatic ferns

Aquatic ferns, such as those in the genus *Azolla* and *Salvinia*, have evolved unique adaptations to thrive in water-logged environments. Unlike their terrestrial counterparts, these ferns rely heavily on water as a medium for spore dispersal. Their spores are often lightweight and hydrophobic, allowing them to float on the water’s surface until they reach a suitable substrate for germination. This passive transport mechanism is highly efficient in aquatic ecosystems, where water currents act as both carrier and disperser. For instance, *Azolla* spores can travel significant distances in slow-moving rivers or ponds, ensuring colonization of new habitats with minimal energy expenditure.

To understand the role of water transport in aquatic fern spore dispersal, consider the structure of their sporangia. These spore-producing organs are typically located on the undersides of floating fronds, positioned to release spores directly into the water. The spores themselves are often coated with a waxy layer that enhances buoyancy and protects them from waterlogging. This design is a testament to the ferns’ evolutionary ingenuity, as it maximizes the chances of successful dispersal in their aquatic niche. For gardeners or researchers cultivating aquatic ferns, ensuring a calm water surface and minimal disturbance can optimize spore release and dispersal.

A comparative analysis of aquatic and terrestrial fern dispersal strategies highlights the importance of water transport. While terrestrial ferns rely on wind or animals for spore dispersal, aquatic ferns harness the natural movement of water. This specialization reduces competition for dispersal agents and aligns with their habitat’s dynamics. For example, in a controlled aquatic environment like a garden pond, introducing gentle water currents using a small pump can mimic natural conditions and enhance spore dispersal. However, care must be taken to avoid strong currents that could damage the delicate fronds or wash spores away too quickly.

Practical tips for observing or aiding water transport in aquatic ferns include monitoring water pH and nutrient levels, as these factors influence spore viability and germination. A pH range of 6.0 to 7.5 is ideal for most aquatic ferns, and maintaining clean, debris-free water ensures unobstructed spore movement. For educational or experimental purposes, placing a fine mesh over the water surface can capture floating spores for closer examination without disrupting their natural dispersal. This hands-on approach not only deepens understanding of aquatic fern biology but also fosters appreciation for their ecological role in water ecosystems.

In conclusion, water transport is a cornerstone of spore dispersal in aquatic ferns, shaped by their anatomical and physiological adaptations. By leveraging water currents and optimizing spore buoyancy, these plants ensure their survival and propagation in challenging environments. Whether in a natural setting or a managed aquatic garden, understanding and supporting these mechanisms can enhance the success of aquatic ferns while offering valuable insights into plant ecology and evolution.

Do Mold Spores Dry Out? Understanding Their Survival and Persistence

You may want to see also

Animal-aided spore dispersal methods

Ferns, ancient plants with a reproductive strategy honed over millions of years, rely on spores for propagation. While wind is the primary disperser, animals play a surprising role in this process, often in subtle yet effective ways. This animal-aided dispersal, though less studied than wind dispersal, offers ferns a targeted and efficient means of colonizing new habitats.

Some animals, through their daily activities, inadvertently become spore couriers. Small mammals, like rodents and shrews, scurrying through underbrush, can pick up spores on their fur. These spores, often sticky or barbed, adhere to the animal's coat and are transported to new locations as the animal forages or seeks shelter. This method, while passive, can be particularly effective in dense forest environments where wind dispersal is limited.

A more direct form of animal-aided dispersal involves birds and insects. Birds, attracted to the vibrant colors or structures of certain fern species, may perch on or near spore-bearing structures, inadvertently brushing against them and dislodging spores. These spores, lightweight and easily airborne, can then be carried on the bird's feathers or in its wake as it flies to new areas. Similarly, insects, such as beetles and ants, may crawl over fern fronds, picking up spores that are later deposited in their nests or foraging sites. This targeted dispersal can lead to the establishment of fern colonies in specific microhabitats, such as tree cavities or ant mounds.

To encourage animal-aided spore dispersal in a garden or natural setting, consider the following: plant fern species known to attract birds or insects, such as those with colorful spores or unique frond structures. Create habitats that support small mammals and insects, like log piles or brush heaps, to increase the likelihood of spore transfer. Avoid excessive use of pesticides, as these can harm the very animals that aid in spore dispersal. By fostering a diverse ecosystem, you can enhance the natural processes that contribute to fern propagation.

While animal-aided spore dispersal may not be as widespread as wind dispersal, its impact on fern populations is significant, particularly in localized ecosystems. This method highlights the intricate relationships between plants and animals, demonstrating how even small interactions can have profound effects on biodiversity. Understanding and supporting these processes can contribute to the conservation of fern species and the overall health of their habitats. By recognizing the role of animals in spore dispersal, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and interconnectedness of the natural world.

Are Spore Syringes Legal in Florida? Understanding the Current Laws

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gravity's role in short-distance spread

Fern spores, being lightweight and numerous, are naturally predisposed to short-distance dispersal by gravity. When mature sporangia on the underside of fern fronds rupture, spores are released and immediately begin their descent. This process, known as *ballistic dispersal*, combines the force of the sporangium’s explosion with the pull of gravity to propel spores downward. However, gravity’s role becomes most pronounced once spores leave the frond. Unlike wind or water, which can carry spores over longer distances, gravity ensures that a significant portion of spores settle within a few meters of the parent plant. This localized dispersal is critical for ferns in dense, shaded environments where competition for space is fierce.

To understand gravity’s efficiency in short-distance spread, consider the mechanics of spore release. Sporangia are often clustered in structures called sori, which are positioned on the lower surface of the frond. When spores are ejected, their initial trajectory is influenced by the sporangium’s orientation and the force of the rupture. Gravity then takes over, pulling spores downward in a predictable arc. This ensures that spores land in a ring-like pattern around the parent plant, typically within a radius of 1 to 3 meters. For gardeners or conservationists, this means that ferns planted in clusters will naturally propagate outward in a gradual, controlled manner, making them ideal for ground cover or understory planting.

While gravity is reliable, it is not without limitations. Spores that land on unsuitable surfaces—such as bare rock or water—may fail to germinate. To maximize the success of gravity-driven dispersal, ensure the surrounding soil is rich in organic matter and retains moisture, as fern spores require a damp substrate to develop into gametophytes. Additionally, avoid placing ferns in areas with heavy foot traffic or frequent disturbance, as this can disrupt the delicate spore layer and reduce germination rates. For optimal results, mimic natural conditions by planting ferns in shaded, humid environments with loamy soil.

A comparative analysis highlights gravity’s role in contrast to other dispersal mechanisms. While wind can carry spores over vast distances, it is unpredictable and often results in spores landing in inhospitable areas. Water dispersal, though effective in certain habitats, is limited to ferns growing near streams or wetlands. Gravity, however, offers consistency and precision, ensuring that spores remain within the immediate vicinity of the parent plant. This makes it particularly advantageous for ferns in stable, resource-rich environments where establishing a strong local presence is more valuable than colonizing new territories.

In practical terms, understanding gravity’s role in fern spore dispersal can inform conservation and cultivation efforts. For instance, when reintroducing ferns to a degraded habitat, plant individuals in staggered rows to create overlapping zones of spore settlement. This approach maximizes ground coverage while minimizing gaps. Similarly, in home gardens, place ferns on elevated surfaces like retaining walls or tiered planters to increase the vertical range of spore dispersal. By working with gravity rather than against it, you can enhance the natural propagation of ferns and create thriving, self-sustaining populations.

Starting with Complexity: Can You Begin Spore with Advanced Creatures?

You may want to see also

Human impact on spore distribution

Fern spores, naturally dispersed by wind, water, and animals, have evolved to travel vast distances, ensuring species survival. However, human activities are reshaping these ancient dispersal patterns in unprecedented ways. Urbanization, deforestation, and climate change fragment habitats, isolating fern populations and reducing genetic diversity. For instance, the construction of roads and buildings disrupts wind currents, hindering the passive dispersal of spores that rely on air movement. Similarly, the loss of waterways due to land development limits water-based dispersal, particularly for species like the royal fern (*Osmunda regalis*), which thrives in wetland environments. These disruptions threaten the resilience of fern populations, making them more vulnerable to environmental changes.

Consider the role of invasive species, a direct consequence of human actions such as global trade and horticulture. Non-native plants introduced to new regions often outcompete indigenous ferns for resources, altering the ecosystem dynamics that once supported spore dispersal. For example, the spread of Japanese knotweed (*Fallopia japonica*) in North America has crowded out native ferns, reducing their ability to release spores effectively. Additionally, invasive animals like rats and deer can inadvertently carry spores to unsuitable habitats, further skewing natural distribution patterns. Addressing this issue requires strict biosecurity measures, such as inspecting imported plants and restoring native vegetation to reclaim invaded areas.

Climate change, driven by human activities, exacerbates these challenges by altering temperature and precipitation patterns. Ferns, often adapted to specific microclimates, struggle to disperse spores in environments where seasonal cues are disrupted. For instance, warmer winters may cause spores to germinate prematurely, reducing their viability. Conversely, prolonged droughts can desiccate spores before they are dispersed. To mitigate these effects, conservationists recommend creating "spore corridors"—connected green spaces that facilitate dispersal between fragmented habitats. Planting fern species with overlapping dispersal seasons can also enhance genetic exchange, ensuring populations remain robust in the face of climate variability.

Finally, human recreational activities, while seemingly benign, can inadvertently impact spore distribution. Hiking, off-road vehicles, and even gardening can disturb soil and vegetation, releasing spores prematurely or transporting them to unsuitable locations. For example, spores clinging to shoes or tires can be carried miles away, colonizing areas where they may not thrive. To minimize this, hikers and gardeners should clean equipment and footwear before entering new areas. Additionally, designating protected zones where human activity is restricted can preserve undisturbed habitats, allowing natural dispersal mechanisms to function unimpeded. By adopting these practices, individuals can play a role in safeguarding fern biodiversity for future generations.

Do Eubacteria Organisms Form Spores? Exploring Their Reproductive Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fern spores are primarily dispersed by wind, taking advantage of their lightweight and small size to travel long distances.

Yes, water can aid in fern spore dispersal, especially in rainy environments, as spores may be carried by raindrop splashes or flowing water.

While less common, animals can inadvertently disperse fern spores by brushing against the spore-bearing structures (sporangia) and carrying them on their fur or feathers.

Fern spores are typically small, lightweight, and often have a hydrophobic surface, which helps them float in the air and resist sticking to surfaces, aiding in wind dispersal.

Some ferns have specialized structures like elastic annuli on their sporangia, which can explosively release spores into the air, increasing the distance and efficiency of dispersal.