Moss spores are produced through a specialized reproductive process in the life cycle of mosses, which are non-vascular plants belonging to the division Bryophyta. Unlike flowering plants, mosses reproduce via alternation of generations, involving both a gametophyte (haploid) and sporophyte (diploid) stage. Spores are generated during the sporophyte phase, which grows from the fertilized egg on the gametophyte. The sporophyte consists of a stalk (seta) and a capsule (sporangium) where meiosis occurs, producing haploid spores. These spores are then released through an opening at the capsule’s apex, often aided by a peristome structure that regulates spore dispersal. Once released, spores can germinate under suitable conditions to develop into new gametophytes, continuing the life cycle. This process ensures the widespread distribution and survival of moss species in diverse environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sporophyte Structure | Mosses produce spores via a sporophyte, which grows from the gametophyte. |

| Capsule (Spore Case) | Spores develop within a capsule at the tip of the sporophyte seta. |

| Operculum | A cap-like structure (operculum) covers the capsule opening. |

| Peristome | Ring of teeth-like structures (peristome) controls spore release. |

| Meiosis | Spores are produced through meiosis, resulting in haploid cells. |

| Spore Type | Mosses typically produce a single type of spore (isosporous). |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are released through wind or water, aided by the peristome. |

| Gametophyte Dependency | Spores germinate into protonemata or gametophytes, requiring moisture. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Spore production is part of the alternation of generations in mosses. |

| Environmental Triggers | Spore release is often triggered by dry conditions or maturity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporophyte Structure: Moss sporophytes have sporangia where spores develop via meiosis

- Meiosis Process: Spores form through meiosis, creating haploid cells in the sporangium

- Sporangium Development: The sporangium matures, producing spores via cell division

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are released through sporangium dehiscence, aided by wind or water

- Environmental Triggers: Sporulation is influenced by light, moisture, and seasonal changes

Sporophyte Structure: Moss sporophytes have sporangia where spores develop via meiosis

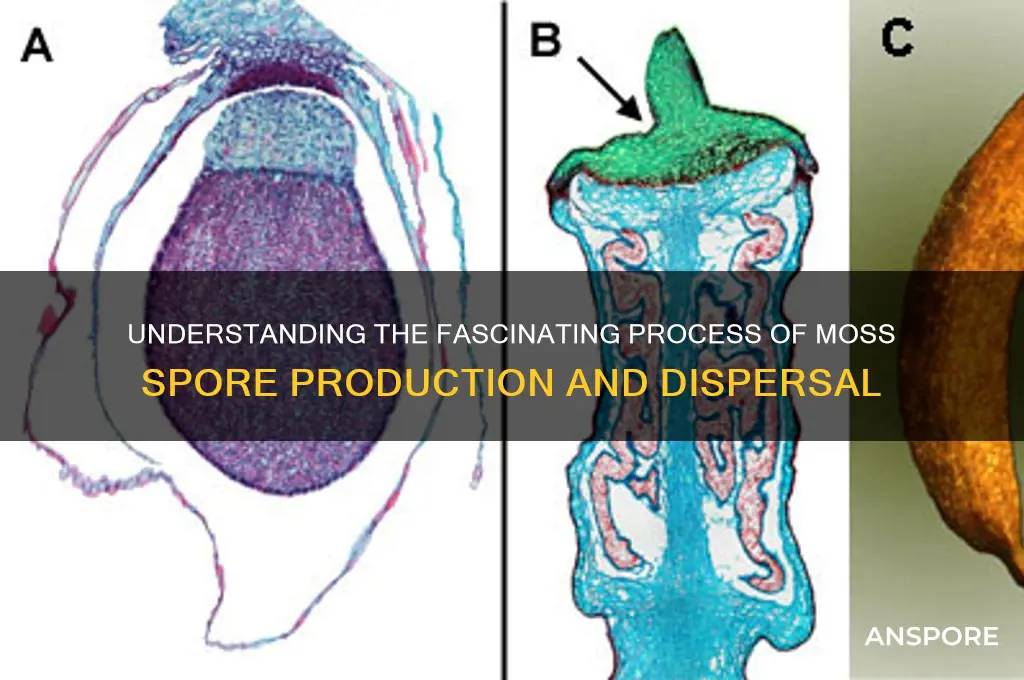

Moss sporophytes, the spore-producing structures of mosses, are fascinating examples of nature's ingenuity in reproduction. These structures are typically found atop a slender stalk, known as a seta, which elevates the sporangium to facilitate spore dispersal. The sporangium, a critical component of the sporophyte, is where the magic of spore production occurs. Within this protective capsule, spores develop through the process of meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid spores. This reduction is essential for the moss's life cycle, allowing for genetic diversity and adaptation to varying environments.

To understand the sporophyte structure, imagine a tiny, elongated capsule, often spherical or oval, perched atop the seta. The sporangium's wall is composed of multiple layers, each serving a specific function. The outer layer, or jacket, provides structural support and protection, while the inner layers are involved in spore development and release. As the spores mature within the sporangium, they undergo meiosis, a complex process that ensures each spore receives a unique combination of genetic material. This genetic diversity is crucial for the survival and evolution of moss species, enabling them to thrive in diverse habitats, from damp forests to arid deserts.

The development of spores via meiosis within the sporangium is a highly regulated process, influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and light. Optimal conditions for spore development typically range between 15-25°C (59-77°F) and require a relative humidity of 60-80%. Under these conditions, the sporophyte can produce thousands of spores, each with the potential to grow into a new moss plant. However, it is essential to note that not all spores will successfully germinate, as factors like predation, competition, and environmental stress can significantly impact their survival.

A comparative analysis of moss sporophytes reveals interesting variations across species. For instance, some mosses have sporangia that are more elongated, while others are nearly spherical. These differences can affect spore dispersal mechanisms, with elongated sporangia often associated with wind dispersal and spherical ones with splash or insect dispersal. Understanding these variations can provide valuable insights into the ecology and evolution of mosses, highlighting the importance of sporophyte structure in shaping their reproductive strategies.

In practical terms, observing moss sporophytes can be a rewarding experience for botanists, hobbyists, and educators alike. To study sporophyte structure, collect samples from diverse habitats, ensuring a representative range of species. Use a magnifying glass or microscope to examine the sporangia, noting their shape, size, and surface features. For a more in-depth analysis, consider staining techniques to visualize the internal structure, including the spore mother cells and developing spores. By engaging with moss sporophytes, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and beauty of these often-overlooked organisms, fostering a greater understanding of the natural world and our place within it.

Casting Plague Spores in MTG: Do You Need Two Targets?

You may want to see also

Meiosis Process: Spores form through meiosis, creating haploid cells in the sporangium

Moss spores are the result of a precise and intricate process rooted in meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid cells. This process is essential for the life cycle of mosses, ensuring genetic diversity and the continuation of the species. Within the sporangium, a specialized structure located at the tip of the moss plant’s sporophyte, meiosis occurs, giving rise to spores that will eventually develop into new gametophyte plants.

To understand this process, consider the steps involved in meiosis. First, the diploid cells within the sporangium undergo DNA replication, doubling their genetic material. Next, these cells enter meiosis I, where homologous chromosomes pair up, exchange genetic material through crossing over, and then separate, reducing the chromosome number from 2n to n. This is followed by meiosis II, which divides the sister chromatids, resulting in four haploid spores. Each spore is now genetically unique, carrying a distinct combination of traits from the parent plant.

The sporangium plays a critical role in this process, acting as a protective chamber where meiosis occurs. Its structure is optimized to facilitate spore development and dispersal. For instance, the sporangium’s wall often contains specialized cells that dry out and split open when mature, releasing the spores into the environment. This mechanism ensures that spores are dispersed efficiently, increasing the likelihood of successful colonization in new habitats.

Practical observation of this process can be achieved by examining mature moss sporophytes under a microscope. Look for the capsule-like sporangium at the tip of the seta (stalk). As the sporangium matures, it becomes translucent, allowing you to observe the haploid spores within. For educational purposes, collecting moss samples from moist, shaded environments and observing them over several weeks can provide insight into the timing and conditions required for spore production.

In comparison to other plant reproductive strategies, mosses rely entirely on spores for dispersal and survival, making meiosis a critical adaptation. Unlike seed-producing plants, which protect their embryos with nutrient-rich seeds, moss spores are lightweight and easily carried by wind or water. This strategy, while vulnerable to environmental conditions, allows mosses to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from dense forests to rocky outcrops. Understanding the meiosis process in mosses not only highlights their unique biology but also underscores the importance of genetic diversity in plant evolution.

Can Spores Survive Anaerobic Conditions? Exploring Their Resilience and Limits

You may want to see also

Sporangium Development: The sporangium matures, producing spores via cell division

The sporangium, a critical structure in the life cycle of mosses, undergoes a remarkable transformation as it matures, ultimately leading to the production of spores through a precise process of cell division. This development is a cornerstone of moss reproduction, ensuring the dispersal and survival of the species. As the sporangium reaches maturity, it becomes a hub of cellular activity, where the intricate dance of mitosis and meiosis gives rise to the next generation of moss plants.

The Maturation Process: A Step-by-Step Guide

Imagine a tiny, capsule-like structure, the sporangium, perched atop a slender seta (stalk) of a moss plant. As it matures, the sporangium's walls thicken, providing a protective environment for the developing spores. This process begins with the enlargement of spore mother cells within the sporangium. These cells, through the process of meiosis, divide to form haploid spores, each containing half the genetic material of the parent plant. This reduction in chromosome number is crucial for sexual reproduction in mosses.

Cell Division: The Heart of Spore Production

Meiosis is not the only cellular process at play here. Following meiosis, the spores undergo a series of mitotic divisions, increasing their numbers exponentially. This rapid cell division is a fascinating aspect of moss biology, as it allows for the production of numerous spores from a single spore mother cell. The sporangium, now a bustling factory of cellular activity, ensures that each spore is equipped with the necessary genetic material and resources for survival.

A Comparative Perspective: Mosses vs. Other Plants

In contrast to flowering plants, which produce seeds containing embryonic plants, mosses rely on spores for reproduction. This distinction highlights the unique evolutionary path of mosses, which have developed a sophisticated mechanism for spore production within the sporangium. While seeds offer a more protected and nutrient-rich environment for embryonic development, moss spores are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions until they find a suitable environment to germinate.

Practical Implications and Takeaways

Understanding sporangium development is not just an academic exercise; it has practical applications in horticulture and conservation. For instance, knowing the optimal conditions for sporangium maturation can aid in the cultivation of mosses for landscaping or ecological restoration. Additionally, studying the cellular processes within the sporangium can provide insights into plant biology, potentially leading to advancements in agriculture and biotechnology. By appreciating the intricacies of moss spore production, we gain a deeper respect for the diversity and adaptability of plant life.

Lysol's Effectiveness: Can It Eliminate Stubborn Bacterial Spores?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are released through sporangium dehiscence, aided by wind or water

Moss spores are not merely ejected into the environment; their release is a precise, orchestrated event. The sporangium, a capsule atop the sporophyte, undergoes dehiscence—a process where it splits open along a line of weakness called the suture. This mechanism ensures spores are expelled efficiently, often in response to environmental cues like humidity or temperature changes. For instance, some moss species time their dehiscence to coincide with dry, windy conditions, maximizing dispersal range. Understanding this process reveals the adaptability of mosses in leveraging their environment for survival.

Wind and water are the unsung heroes of spore dispersal, each playing a distinct role. Wind, with its unpredictable yet far-reaching nature, carries lightweight spores over vast distances, increasing the chances of colonization in new habitats. To aid this, moss spores are often equipped with elaters—spring-like structures that help them catch air currents. In contrast, water dispersal is more localized but equally effective, particularly in humid or aquatic environments. Spores released near water bodies can be carried downstream, colonizing moist substrates along the way. This dual strategy ensures mosses can thrive in diverse ecosystems, from arid rock faces to lush rainforests.

Consider the practical implications of these dispersal mechanisms for gardeners or ecologists. If cultivating moss in a garden, positioning moss-covered rocks or soil in elevated, windy areas can enhance spore spread. Alternatively, placing moss near water features like ponds or streams encourages water-mediated dispersal. For conservation efforts, understanding these mechanisms helps in predicting moss colonization patterns, aiding in habitat restoration projects. For example, reintroducing moss spores upstream can facilitate their natural dispersal to degraded areas downstream.

A comparative analysis highlights the efficiency of sporangium dehiscence versus other spore release methods. Unlike ferns, which rely on gradual spore release through ostioles, mosses employ a rapid, explosive mechanism. This ensures a higher concentration of spores is released at once, increasing the likelihood of successful germination. Additionally, the reliance on wind and water contrasts with seed plants, which often depend on animals for dispersal. Mosses’ simpler yet effective strategy underscores their evolutionary success in colonizing diverse, often harsh environments.

Finally, the interplay between sporangium dehiscence and environmental factors offers a fascinating example of nature’s ingenuity. For instance, some moss species have sporangia that twist or dry out in specific ways to enhance spore ejection. This biomechanical precision, combined with the passive yet powerful forces of wind and water, ensures moss spores reach optimal germination sites. By studying these mechanisms, scientists can draw inspiration for engineering solutions, such as designing micro-dispersal systems for agricultural or ecological applications. In essence, the humble moss spore’s journey is a testament to the elegance of natural design.

Can Mold Spores Survive on Metal Surfaces? Facts and Insights

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: Sporulation is influenced by light, moisture, and seasonal changes

Moss sporulation is a finely tuned response to environmental cues, with light acting as a critical catalyst. In nature, mosses often thrive in shaded habitats, but it’s the shift in light quality—specifically the increase in red to far-red light ratios—that signals the transition from gametophyte to sporophyte growth. This change mimics the canopy gaps created by falling leaves or branches, indicating an opportunity for spore dispersal. Laboratory studies have shown that exposure to 16 hours of light per day, particularly in the 660 nm (red) spectrum, accelerates sporulation in species like *Physcomitrium patens*. For hobbyists cultivating moss, strategically placing grow lights with adjustable spectrums can replicate these conditions, ensuring sporophytes develop within 4–6 weeks under optimal settings.

Moisture, while essential for moss survival, plays a paradoxical role in sporulation. While gametophytes require consistent moisture to photosynthesize and grow, sporophytes often need a brief drying period to initiate spore release. This mechanism prevents spores from germinating prematurely in the same damp environment where the parent moss resides. Field observations reveal that species like *Sphagnum* mosses, prevalent in peatlands, sporulate most effectively after a 24–48 hour dry spell following heavy rainfall. Gardeners aiming to encourage sporulation should mimic this cycle by allowing the moss substrate to dry slightly before rehydrating, ensuring the sporophytes mature without rotting.

Seasonal changes act as a temporal regulator, aligning sporulation with the most favorable conditions for spore survival and dispersal. In temperate regions, many moss species sporulate in late spring or early summer, capitalizing on warmer temperatures and increased airflow. For instance, *Bryum argenteum* typically releases spores in June, coinciding with longer daylight hours and moderate humidity. In contrast, tropical mosses may sporulate year-round but show peak activity during the wet season. For those studying or cultivating moss, tracking local phenology—such as the first flowering of nearby plants—can serve as a natural calendar to predict and prepare for sporulation events.

The interplay of these environmental triggers underscores the adaptability of mosses to diverse ecosystems. Light, moisture, and seasonal cues do not act in isolation but form a complex network that fine-tunes the timing and success of sporulation. For example, a sudden increase in light combined with a brief dry period in early summer creates the ideal window for spore release in *Ceratodon purpureus*. By understanding these relationships, researchers and enthusiasts can manipulate environments to study sporulation dynamics or propagate rare species. Practical applications include using shade cloths to control light exposure in moss gardens or monitoring humidity levels with hygrometers to replicate natural drying cycles.

Ultimately, mastering the environmental triggers of moss sporulation requires observation, experimentation, and patience. Whether in a laboratory or a backyard terrarium, mimicking the nuanced conditions of light, moisture, and seasonality can unlock the reproductive potential of these resilient plants. For instance, a simple setup involving LED grow lights, a misting schedule, and a seasonal diary can transform a casual moss collection into a thriving sporulation study. By respecting the ecological rhythms that govern mosses, enthusiasts can not only witness the beauty of sporulation but also contribute to the conservation and propagation of these vital organisms.

Do Points Really Matter in Spore's Tribal Stage? Exploring Gameplay

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Moss spores are produced in structures called sporangia, which develop on the sporophyte generation of the moss life cycle.

The production of moss spores is triggered by environmental factors such as changes in light, humidity, and temperature, which signal the sporophyte to mature and release spores.

Spores are produced at the tip of the sporophyte, a stalk-like structure that grows from the gametophyte (the leafy, green part of the moss).

Moss spores are dispersed through wind, water, or animals. The sporangium dries out and splits open, releasing the spores into the environment.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)