Fungal spores are formed through a variety of reproductive processes, depending on the fungal species and its life cycle. In general, spores are produced either asexually, through processes like budding, fragmentation, or the formation of specialized structures such as conidia, or sexually, via the fusion of gametes and subsequent meiosis. Asexual spores, like conidia, are typically produced on the tips or sides of specialized hyphae called conidiophores, while sexual spores, such as ascospores or basidiospores, develop within protective structures like asci or basidia, respectively. These spores serve as a means of dispersal, allowing fungi to colonize new environments, survive harsh conditions, and propagate their genetic material. The formation of spores is a critical aspect of the fungal life cycle, ensuring their survival and adaptability in diverse ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Reproduction | Both sexual and asexual |

| Asexual Spores | Formed through mitosis (e.g., conidia, spores, chlamydospores) |

| Sexual Spores | Formed through meiosis (e.g., asci, basidiospores, zygospores) |

| Location of Formation | Specialized structures like sporangia, asci, basidia, or directly on hyphae |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Wind, water, insects, animals, or passive release |

| Environmental Triggers | Nutrient depletion, stress, or specific environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity) |

| Resistance | Many spores are resistant to harsh conditions (e.g., desiccation, heat, chemicals) |

| Germination | Spores remain dormant until favorable conditions trigger germination |

| Genetic Diversity | Sexual spores increase genetic diversity; asexual spores maintain clonal populations |

| Examples of Structures | Sporangiospores (in Zygomycota), conidia (in Ascomycota and Deuteromycota), basidiospores (in Basidiomycota) |

| Ecological Role | Essential for fungal survival, dispersal, and colonization of new habitats |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Asexual Sporulation: Fungi produce spores like conidia via mitosis, often on specialized structures

- Sexual Sporulation: Meiosis forms spores (e.g., asci, basidiospores) in reproductive structures

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like light, nutrients, and stress induce spore formation

- Spore Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, animals, or explosive release aid spore spread

- Morphological Development: Spores develop from hyphal cells, maturing in distinct shapes and sizes

Asexual Sporulation: Fungi produce spores like conidia via mitosis, often on specialized structures

Fungi employ a remarkable strategy for survival and propagation through asexual sporulation, a process that hinges on the production of spores like conidia via mitosis. Unlike sexual reproduction, which involves the fusion of gametes, asexual sporulation is a rapid and efficient method of replication. This process occurs predominantly on specialized structures such as conidiophores, which serve as the launching pads for these microscopic survival units. Understanding this mechanism not only sheds light on fungal biology but also highlights its implications in agriculture, medicine, and ecology.

Consider the lifecycle of *Aspergillus*, a common fungus found in soil and decaying matter. When environmental conditions are favorable, *Aspergillus* develops conidiophores, tall, stalk-like structures that bear conidia at their tips. These conidia are formed through mitosis, ensuring each spore carries an exact genetic copy of the parent fungus. This uniformity is both a strength and a limitation—while it allows for rapid colonization of new habitats, it restricts genetic diversity, which can be crucial for adapting to changing environments. For instance, in a controlled laboratory setting, researchers can manipulate humidity and nutrient levels to optimize conidia production, a technique often used in biotechnology to produce enzymes or antibiotics.

The formation of conidia is not merely a biological curiosity but a process with practical implications. In agriculture, fungal spores like conidia can act as both allies and adversaries. Beneficial fungi, such as *Trichoderma*, produce conidia that colonize plant roots, enhancing nutrient uptake and protecting against pathogens. Conversely, harmful fungi like *Botrytis cinerea* (gray mold) release conidia that devastate crops, causing significant economic losses. Farmers can mitigate these risks by monitoring environmental conditions—conidia production peaks in high humidity and moderate temperatures—and applying fungicides strategically. For example, spraying sulfur-based fungicides at a concentration of 2-3 grams per liter of water can effectively suppress conidia formation in susceptible crops.

A closer examination of the structures involved reveals the precision of fungal design. Conidiophores are not just simple stalks; they are highly specialized organs with distinct regions like the stipe (support structure) and vesicle (spore-bearing head). The vesicle, in turn, gives rise to sterigmata, tiny projections upon which conidia develop. This intricate architecture ensures efficient spore dispersal, often aided by wind or water. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms at home, mimicking these conditions can enhance spore production. A simple setup involving a humidifier to maintain 80-90% humidity and a sterile growth medium can encourage conidiophore development in species like *Penicillium*.

In conclusion, asexual sporulation through mitosis is a testament to fungal adaptability and resilience. By producing conidia on specialized structures, fungi ensure their survival across diverse environments. Whether harnessed for biotechnological applications or managed in agricultural settings, understanding this process empowers us to work with—or against—these microscopic powerhouses. Practical tips, such as controlling humidity and using targeted fungicides, underscore the tangible impact of this knowledge in everyday scenarios.

Do Clorox Wipes Effectively Kill C. Diff Spores? Find Out Here

You may want to see also

Sexual Sporulation: Meiosis forms spores (e.g., asci, basidiospores) in reproductive structures

Fungal spores are not merely dust-like particles; they are the products of intricate reproductive strategies. Among these, sexual sporulation stands out as a sophisticated process where meiosis plays a pivotal role. Unlike asexual methods, which clone the parent organism, sexual sporulation introduces genetic diversity by combining genetic material from two parents. This diversity is crucial for fungi to adapt to changing environments, resist pathogens, and exploit new ecological niches.

Consider the formation of asci in Ascomycetes, commonly known as sac fungi. Here, two haploid cells—often from different mating types—fuse to form a diploid zygote. This zygote undergoes meiosis, a reductive division that halves the chromosome number, producing four haploid nuclei. These nuclei are then packaged into spore-like structures called ascospores within a sac-like ascus. Each ascus typically contains eight ascospores, which are later released to germinate under favorable conditions. This process ensures genetic recombination, making each ascospore genetically unique.

Basidiomycetes, or club fungi, employ a similar yet distinct mechanism. In this group, meiosis occurs within a specialized structure called the basidium. Two haploid mycelia fuse to form a dikaryotic cell, where two nuclei coexist without fusing. As the basidium matures, the nuclei pair up, undergo meiosis, and migrate into four basidiospores. These spores are often borne on slender projections called sterigmata, giving the basidium its club-like appearance. This method not only ensures genetic diversity but also allows for efficient spore dispersal, often aided by wind or water.

Practical applications of understanding sexual sporulation extend beyond academic curiosity. For instance, in agriculture, knowing the life cycle of pathogenic fungi like *Magnaporthe oryzae* (rice blast fungus) can inform fungicide timing. Since sexual spores are often more resilient and genetically diverse, targeting them during their formation or release can mitigate crop damage. Similarly, in mycoremediation—using fungi to degrade pollutants—encouraging sexual sporulation can enhance fungal adaptability to toxic environments.

In summary, sexual sporulation through meiosis is a cornerstone of fungal evolution and survival. Whether in the ascus of a yeast or the basidium of a mushroom, this process underscores the elegance of nature’s design. By studying these mechanisms, we not only deepen our understanding of fungal biology but also unlock practical solutions for agriculture, ecology, and biotechnology.

Mold Spores in Rain: Unseen Passengers and Their Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: Factors like light, nutrients, and stress induce spore formation

Fungal spore formation is not a random event but a highly regulated process influenced by environmental cues. Among these, light, nutrients, and stress act as critical triggers, each playing a unique role in signaling the fungus to initiate sporulation. Light, for instance, is detected by photoreceptors in fungi, which can either promote or inhibit spore formation depending on the species and wavelength. Blue light, in particular, has been shown to stimulate sporulation in *Aspergillus nidulans* by activating the light-sensitive protein LreA, leading to the expression of genes involved in conidiation. Conversely, red light may suppress sporulation in some fungi, highlighting the specificity of light responses.

Nutrient availability is another pivotal factor, with fungi often transitioning to spore formation when resources become scarce. For example, nitrogen limitation triggers sporulation in *Neurospora crassa* by activating the transcription factor NIT2, which upregulates genes necessary for spore development. Similarly, carbon starvation can induce sporulation in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, where the Snf1 kinase pathway senses low glucose levels and initiates the formation of ascospores. These nutrient-driven responses ensure fungal survival during unfavorable conditions, allowing spores to disperse and colonize new environments when resources become available again.

Stress, whether abiotic or biotic, also serves as a potent environmental trigger for spore formation. Osmotic stress, caused by high salt concentrations, induces sporulation in *Magnaporthe oryzae*, the rice blast fungus, as a protective mechanism. Similarly, oxidative stress, often triggered by reactive oxygen species (ROS), can activate sporulation pathways in *Candida albicans*, enabling it to withstand harsh conditions. Even mechanical stress, such as physical disruption of the fungal colony, has been observed to accelerate spore production in some species, demonstrating the adaptability of fungi to diverse stressors.

Understanding these environmental triggers has practical implications, particularly in agriculture and medicine. For instance, manipulating light exposure or nutrient levels could control fungal sporulation in crop fields, reducing the spread of pathogens like *Botrytis cinerea*, which causes gray mold. In clinical settings, identifying stress-induced sporulation pathways could lead to new antifungal strategies by targeting the mechanisms fungi use to survive under stress. By harnessing this knowledge, we can develop more effective methods to manage fungal growth and mitigate its impact on human health and ecosystems.

In conclusion, light, nutrients, and stress are not mere environmental factors but precise regulators of fungal spore formation. Their interplay with fungal physiology underscores the sophistication of these organisms in responding to their surroundings. Whether through photoreceptor activation, nutrient-sensing pathways, or stress-induced signaling, fungi have evolved diverse strategies to ensure their survival and propagation. This understanding not only deepens our appreciation of fungal biology but also opens avenues for practical applications in controlling fungal populations and combating fungal diseases.

Can Mold Spores Thrive in Paint? Uncovering the Hidden Risks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, animals, or explosive release aid spore spread

Fungal spores are not just miniature replicas of their parent organisms; they are highly specialized structures designed for survival and dispersal. Once formed, their journey to new habitats relies on a variety of mechanisms, each tailored to maximize reach and efficiency. Wind, water, animals, and even explosive release play pivotal roles in this process, ensuring that fungi can colonize diverse environments, from dense forests to arid deserts.

Consider the role of wind, the most common dispersal agent for fungal spores. Fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* produce lightweight, dry spores that can be carried over vast distances by air currents. These spores are often equipped with structures like wings or hairs, increasing their aerodynamic potential. For instance, the spores of *Claviceps purpurea*, the ergot fungus, are so lightweight that a single sneeze could disperse them across an entire field. To harness this mechanism, farmers and gardeners should avoid working in windy conditions when managing fungal infections, as this can inadvertently spread spores to healthy plants.

Water, though less universal than wind, is equally effective for fungi thriving in moist environments. Aquatic fungi like *Saprolegnia* release spores that float on water surfaces, drifting until they encounter a suitable substrate. Even terrestrial fungi, such as those in the genus *Phycomyces*, can utilize rain splashes to disperse their spores. A practical tip for controlling water-dispersed fungi is to ensure proper drainage in gardens and greenhouses, reducing standing water that could facilitate spore movement.

Animals, both large and small, act as unwitting carriers of fungal spores. Spores can adhere to fur, feathers, or even the feet of insects, traveling significant distances before being deposited in new locations. For example, the spores of *Geastrum* (earthstar fungi) are dispersed by insects attracted to their pungent odor. To minimize animal-mediated dispersal, maintain clean environments and use barriers like nets to protect crops from spore-carrying pests.

Perhaps the most dramatic dispersal mechanism is explosive release, employed by fungi like *Pilobolus*, which can eject spores up to 2 meters with an internal pressure of 1.5 megapascals. This method ensures rapid and targeted dispersal, often onto nearby vegetation. While this mechanism is less common, it highlights the ingenuity of fungal adaptations. For enthusiasts studying such fungi, observing spore discharge under a microscope can provide fascinating insights into the physics of fungal survival strategies.

In conclusion, fungal spore dispersal is a multifaceted process, leveraging natural forces and biological interactions to ensure widespread propagation. Understanding these mechanisms not only deepens our appreciation of fungal ecology but also equips us with practical tools to manage fungal populations in agriculture, horticulture, and beyond. Whether through wind, water, animals, or explosive release, fungi have mastered the art of spreading their influence far and wide.

Pine Tree Reproduction: Do They Use Spores or Seeds?

You may want to see also

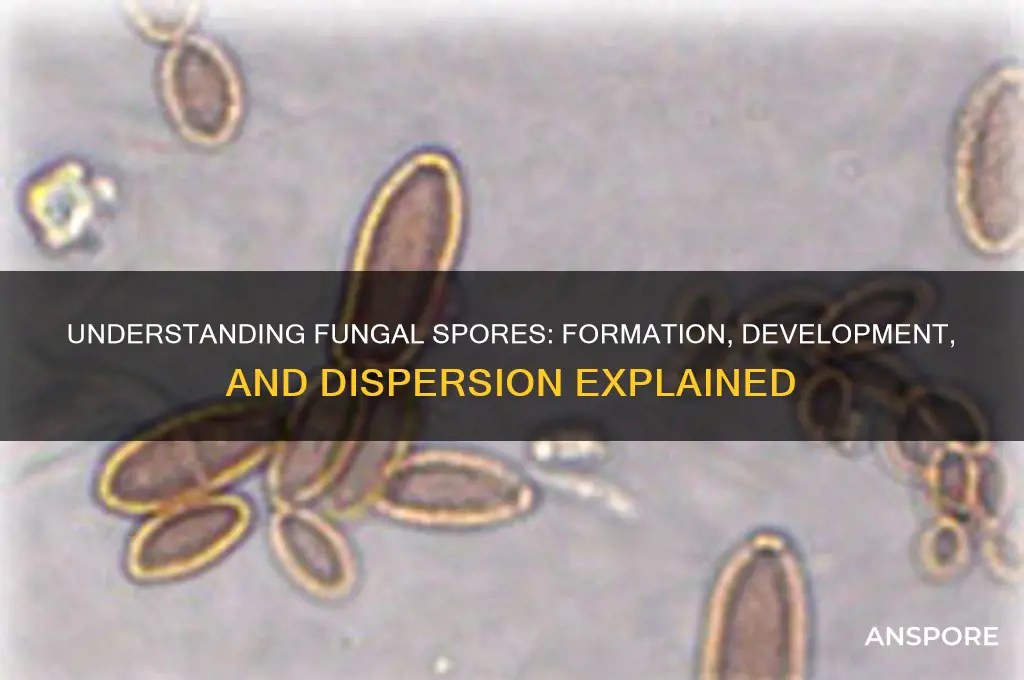

Morphological Development: Spores develop from hyphal cells, maturing in distinct shapes and sizes

Fungal spores are not born equal; their diversity begins at the cellular level. Hyphal cells, the building blocks of fungal structures, undergo a metamorphosis to form spores, each with a unique destiny. This transformation is a masterpiece of morphological development, where shape and size become the signatures of spore identity. Imagine a single hyphal cell, once part of a uniform network, now swelling, constricting, or branching to create a spore that will defy its original form. This process is not random but a precise, genetically orchestrated event, ensuring that each spore type—whether it’s a smooth, round conidia or a complex, multi-celled ascospore—is tailored for its role in survival and dispersal.

To understand this development, consider the steps a hyphal cell undergoes. First, it receives a signal—environmental stress, nutrient depletion, or a genetic trigger—prompting it to differentiate. The cell wall thickens, and internal structures reorganize. For example, in *Aspergillus*, a hyphal cell may form a specialized structure called a sterigma, which supports the developing conidium. As the spore matures, it accumulates storage compounds like lipids and carbohydrates, essential for withstanding harsh conditions. The final shape—oval, cylindrical, or even star-shaped—is dictated by the species and its ecological niche. A *Penicillium* spore, for instance, is smooth and green, optimized for wind dispersal, while a *Neurospora* ascospore is dark and resilient, designed for long-term dormancy.

The size of spores is equally critical, often correlating with their dispersal mechanism and survival strategy. Small spores, like those of *Fusarium* (2–5 μm), are easily carried by air currents, maximizing their reach. Larger spores, such as those of *Coprinus* (10–20 μm), may rely on water or insects for transport but carry more resources for germination. This size variation is not arbitrary; it’s a balance between mobility and self-sufficiency. For practical applications, understanding spore size can inform control measures—smaller spores may require HEPA filters for removal, while larger ones can be trapped by coarse screens.

A comparative analysis reveals the elegance of this system. In basidiomycetes, like mushrooms, spores develop externally on club-shaped basidia, their size and shape optimized for ballistic ejection. In contrast, ascomycetes, like yeasts and molds, produce spores internally within sac-like asci, often with intricate appendages for adhesion. This diversity is not just evolutionary flair; it’s a survival toolkit. For instance, the elongated spores of *Claviceps* (ergot fungus) are adapted to infect grass florets, while the spherical spores of *Candida* facilitate rapid colonization of host tissues.

In conclusion, the morphological development of fungal spores from hyphal cells is a testament to nature’s ingenuity. By maturing into distinct shapes and sizes, spores are equipped for their specific roles—whether it’s traveling across continents or surviving extreme conditions. For researchers and practitioners, understanding this process offers insights into fungal ecology, disease control, and biotechnology. For example, knowing that *Botrytis cinerea* produces small, airborne spores can guide the timing of fungicide applications in vineyards. Similarly, recognizing the large, sticky spores of *Puccinia* (rust fungi) can inform strategies for preventing crop infections. This knowledge transforms spores from microscopic curiosities into actionable targets for management and innovation.

Exploring Spore: Can Player-Created Races Engage in Combat?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungal spores are formed through specialized reproductive structures such as sporangia, asci, or basidia, depending on the fungal species. They develop via mitosis or meiosis, with asexual spores (e.g., conidia) produced by mitosis and sexual spores (e.g., asci or basidiospores) produced by meiosis.

Fungal spore formation is triggered by environmental factors such as nutrient depletion, changes in temperature, humidity, or light. These conditions signal the fungus to enter a reproductive phase to ensure survival and dispersal.

No, fungal spores are formed differently depending on the fungal group. For example, molds produce spores in structures called sporangia, while yeasts may bud or form ascospores. The method varies based on whether the fungus reproduces asexually or sexually.

Fungal spores disperse through various mechanisms, including wind, water, insects, or animals. Some spores are lightweight and easily carried by air currents, while others may stick to surfaces or be ingested and spread by organisms.