Spores are microscopic, reproductive structures produced by various organisms, including plants, fungi, and some bacteria, as a means of asexual or sexual reproduction. They are highly resilient and can survive in harsh environmental conditions, allowing them to disperse widely and germinate when favorable conditions return. In plants, spores are typically created through the process of sporogenesis, which occurs in specialized structures like sporangia. For example, ferns produce spores on the undersides of their leaves, while mosses release spores from capsules. Fungi, such as mushrooms, generate spores in structures like gills or pores, which are then dispersed by wind or water. The creation of spores involves cell division, often through meiosis in sexual reproduction, resulting in genetically diverse offspring. This adaptability and durability make spores a crucial mechanism for the survival and propagation of many species across diverse ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process | Spores are typically created through a process called sporulation, which is a specialized form of cell division in certain organisms, primarily fungi, bacteria, and plants. |

| Type of Spores | Spores can be classified into different types based on their origin and function, such as endospores (bacterial), conidia (fungal), zygotes (fungal), meiospores (plant), and mitospores (fungal/plant). |

| Function | Spores serve as a means of reproduction, survival, and dispersal in adverse environmental conditions (e.g., heat, desiccation, chemicals). |

| Structure | Spores are often dormant, highly resistant, and have a protective outer layer (e.g., spore coat in bacteria, cell wall in fungi) to withstand harsh conditions. |

| Formation in Bacteria | Endospores are formed within a bacterial cell through a process involving DNA replication, septum formation, and engulfment of one cell by another, resulting in a resistant spore. |

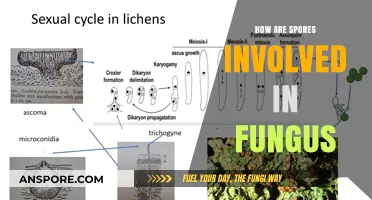

| Formation in Fungi | Spores are produced via sexual (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores) or asexual (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) reproduction, often involving specialized structures like sporangia or asci. |

| Formation in Plants | Spores are produced in plants via meiosis in structures like sporangia (e.g., ferns, mosses) and are released for dispersal and germination. |

| Germination | Spores remain dormant until favorable conditions trigger germination, where they develop into new organisms. |

| Dispersal | Spores are dispersed through air, water, or animals, allowing them to colonize new environments. |

| Resistance Mechanisms | Spores exhibit resistance through reduced metabolic activity, thick protective layers, and DNA repair mechanisms to survive extreme conditions. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: Cells undergo sporulation, a complex process to form spores under stress or nutrient depletion

- Types of Spores: Spores vary (e.g., endospores, conidia) based on organism and environmental adaptation mechanisms

- Genetic Regulation: Specific genes control sporulation, triggered by environmental cues and intracellular signals

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like starvation, temperature, and pH induce spore formation in microorganisms

- Spore Structure: Spores have protective layers (e.g., exosporium, cortex) for survival in harsh conditions

Sporulation Process: Cells undergo sporulation, a complex process to form spores under stress or nutrient depletion

Under stress or nutrient depletion, certain bacteria, such as *Bacillus subtilis* and *Clostridium botulinum*, initiate a survival mechanism known as sporulation. This process transforms a vegetative cell into a highly resilient spore capable of enduring extreme conditions like heat, radiation, and desiccation. Unlike replication, sporulation is not about growth but about preservation. The cell asymmetrically divides, forming a smaller forespore within the larger mother cell. This forespore eventually develops a protective coat and becomes metabolically dormant, ensuring long-term survival until favorable conditions return.

The sporulation process is tightly regulated by a genetic cascade involving sigma factors, proteins that direct RNA polymerase to transcribe specific genes. For instance, in *Bacillus subtilis*, the master regulator Spo0A activates genes necessary for the initial stages of sporulation. As the process progresses, different sigma factors take over, ensuring the precise timing and execution of each step. This intricate regulation highlights the cell’s ability to respond dynamically to environmental cues, prioritizing survival over immediate metabolic needs.

One of the most remarkable aspects of sporulation is the formation of the spore’s protective layers. The cortex, composed of modified peptidoglycan, provides structural integrity, while the coat, made of over 70 proteins, acts as a barrier against enzymes and chemicals. In some species, an additional layer called the exosporium offers further protection. These layers are assembled with precision, demonstrating the cell’s capacity to engineer complex structures under duress. For example, the coat proteins self-assemble in a defined order, a process akin to building a suit of armor from the inside out.

Practical applications of sporulation extend beyond microbiology. Understanding this process has led to advancements in food preservation, as spores of bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* are resistant to traditional canning methods. To ensure safety, food manufacturers use high-pressure processing or temperatures exceeding 121°C (250°F) for at least 3 minutes to destroy spores. Conversely, sporulation is harnessed in biotechnology to produce enzymes and vaccines, as spores can serve as stable delivery vehicles. For instance, *Bacillus* spores are used in probiotics due to their ability to survive the gastrointestinal tract.

While sporulation is a survival strategy for bacteria, it poses challenges for human health and industry. Spores of pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* can persist in hospital environments, causing recurrent infections. Effective disinfection requires spore-specific agents such as hydrogen peroxide or chlorine dioxide. In agriculture, spore-forming bacteria can contaminate soil and crops, necessitating targeted treatments. By studying sporulation, scientists aim to develop inhibitors that disrupt spore formation, offering new avenues for antimicrobial therapy and contamination control.

Understanding Moss Spores: Are They Diplohaplontic? A Detailed Look

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Spores vary (e.g., endospores, conidia) based on organism and environmental adaptation mechanisms

Spores are not a one-size-fits-all solution for survival; they are as diverse as the organisms that produce them. This diversity is a testament to the intricate ways life adapts to environmental challenges. From the resilient endospores of bacteria to the airborne conidia of fungi, each type of spore is a specialized structure designed to ensure the continuation of its species under specific conditions. Understanding these variations sheds light on the remarkable strategies organisms employ to endure and thrive in diverse ecosystems.

Consider endospores, the hardiest of bacterial survival mechanisms. Produced by genera like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, these spores are formed within the bacterial cell through a process called sporulation. Endospores are metabolically dormant and encased in multiple protective layers, including a tough outer coat and a cortex rich in peptidoglycan. This design allows them to withstand extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, and desiccation. For instance, endospores can survive boiling temperatures for hours, making them a challenge in food preservation and sterilization processes. Their ability to remain viable for centuries underscores their role as a long-term survival strategy in harsh environments.

In contrast, conidia represent a different spore type, primarily associated with fungi. These asexual spores are produced externally on specialized structures like conidiophores. Unlike endospores, conidia are not dormant but remain metabolically active, ready to germinate when conditions are favorable. Their lightweight structure and aerodynamic shape enable dispersal through air currents, facilitating colonization of new habitats. For example, the conidia of *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* are ubiquitous in indoor and outdoor environments, playing roles in both decomposition and food spoilage. While less resilient than endospores, conidia’s rapid production and dispersal make them effective for quick adaptation to changing environments.

The distinction between endospores and conidia highlights how spore types are tailored to specific ecological niches. Endospores prioritize durability, ensuring survival in extreme conditions, while conidia emphasize dispersal and rapid colonization. Other spore types, such as zygospores in fungi or spores in plants like ferns, further illustrate this adaptability. Zygospores, formed through sexual reproduction, are thick-walled and dormant, suited for long-term survival in soil. Fern spores, on the other hand, are lightweight and dispersed by wind, enabling them to reach new habitats and germinate into gametophytes.

Practical implications of spore diversity are vast. In healthcare, understanding endospores is crucial for effective sterilization techniques, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes to ensure their destruction. In agriculture, managing conidia dispersal can help control fungal diseases in crops. For hobbyists cultivating plants like ferns, knowing the optimal conditions for spore germination—such as a humid environment and indirect light—can enhance propagation success. By recognizing the unique characteristics and functions of different spore types, we can better navigate their impact on health, industry, and the natural world.

Does Lumber Direct Sell Milky Spore Powder or Granules?

You may want to see also

Genetic Regulation: Specific genes control sporulation, triggered by environmental cues and intracellular signals

Sporulation, the process by which certain organisms form spores, is a highly regulated genetic program essential for survival in harsh conditions. At its core, this process is governed by specific genes that respond to environmental cues and intracellular signals, orchestrating a complex cascade of events. For instance, in *Bacillus subtilis*, the master regulator gene *spo0A* is activated when nutrients are scarce, triggering the expression of genes necessary for spore formation. This genetic switch highlights the precision with which organisms adapt to their surroundings.

Consider the role of environmental cues in initiating sporulation. In fungi like *Aspergillus*, high temperatures and nutrient depletion activate genes such as *brlA*, which directs the development of spore-forming structures. Similarly, in plants, drought or salinity can induce the expression of genes involved in pollen or seed spore formation, ensuring species survival. These examples illustrate how external stressors act as signals, fine-tuning genetic responses to optimize spore production. For practical applications, understanding these triggers can inform agricultural strategies, such as breeding crops with enhanced stress-responsive sporulation genes.

Intracellular signals also play a critical role in regulating sporulation. In yeast, the MAP kinase pathway is activated by pheromones, leading to the expression of genes required for spore wall synthesis. This internal signaling ensures that sporulation occurs only when conditions are optimal, such as during mating. Similarly, in bacteria, the accumulation of signaling molecules like Spo0A~P acts as a threshold mechanism, ensuring that sporulation genes are activated only when a critical concentration is reached. This internal regulation prevents wasteful energy expenditure and ensures survival under stress.

To harness the potential of sporulation in biotechnology, researchers can manipulate these genetic pathways. For example, overexpressing *spo0A* in *Bacillus* can enhance spore yield, beneficial for probiotic production. In plants, CRISPR-based editing of sporulation genes could improve crop resilience to climate change. However, caution is necessary; altering these pathways can disrupt normal growth cycles. For instance, constitutive activation of sporulation genes in yeast can lead to reduced vegetative growth. Thus, precise control and thorough testing are essential when engineering sporulation mechanisms.

In summary, genetic regulation of sporulation is a finely tuned process driven by environmental and intracellular signals. By understanding and manipulating these pathways, scientists can unlock new possibilities in agriculture, biotechnology, and medicine. Whether enhancing crop resilience or optimizing microbial production, the key lies in deciphering the genetic code that governs spore creation. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of life’s survival strategies but also empowers us to innovate sustainably.

Can Dawn Dish Soap Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores in Your Home?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers: Factors like starvation, temperature, and pH induce spore formation in microorganisms

Microorganisms, when faced with harsh environmental conditions, often resort to spore formation as a survival strategy. This process, known as sporulation, is triggered by specific environmental factors that signal impending danger to the organism's survival. Among these triggers, starvation, temperature fluctuations, and pH changes play a pivotal role in inducing spore formation. For instance, when nutrients become scarce, bacteria like *Bacillus subtilis* initiate a complex genetic program that leads to the development of endospores, which can withstand extreme conditions for extended periods.

Consider the impact of temperature on spore formation. In *Bacillus* species, exposure to temperatures above 45°C (113°F) or below 10°C (50°F) can accelerate sporulation. This temperature-induced response is not arbitrary; it is a finely tuned mechanism that ensures the organism’s survival in environments where temperature extremes are common, such as soil or hot springs. Similarly, pH levels outside the optimal range (typically 6.5–7.5 for most bacteria) can trigger sporulation. For example, a sudden drop in pH to levels below 5.0 can prompt *Clostridium* species to form spores, protecting their genetic material from acid-induced damage.

Starvation, perhaps the most universal trigger, forces microorganisms to conserve energy and resources. When essential nutrients like carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus are depleted, cells redirect their metabolic pathways toward spore formation. This process involves the synthesis of a thick, protective spore coat and the dehydration of the cell’s interior, reducing metabolic activity to near-zero levels. For practical purposes, researchers often induce sporulation in laboratory settings by culturing bacteria in nutrient-depleted media, such as sporulation agar, which mimics starvation conditions.

While these environmental triggers are well-documented, their interplay adds another layer of complexity. For instance, combined stress from starvation and high temperatures can accelerate sporulation more effectively than either factor alone. This synergistic effect highlights the adaptability of microorganisms in responding to multiple environmental challenges simultaneously. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for industries like food preservation, where controlling sporulation can prevent contamination by spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium botulinum*.

In conclusion, environmental triggers such as starvation, temperature, and pH are not mere stressors but precise signals that induce spore formation in microorganisms. By manipulating these factors, scientists can study sporulation mechanisms, develop antimicrobial strategies, and even harness spores for biotechnological applications. Whether in nature or the lab, these triggers underscore the resilience and ingenuity of microbial life in the face of adversity.

Do Marijuana Tinctures Contain Spores? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: Spores have protective layers (e.g., exosporium, cortex) for survival in harsh conditions

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of certain plants, fungi, and bacteria, owe their survival in harsh environments to intricate protective layers. These layers, akin to a suit of armor, shield the spore’s genetic material from desiccation, radiation, and extreme temperatures. For instance, the exosporium, the outermost layer in some bacterial spores (like *Bacillus anthracis*), acts as a barrier against chemicals and enzymes, while the cortex, rich in peptidoglycan, provides structural integrity and resists mechanical stress. Together, these layers ensure spores can endure conditions that would destroy most life forms, sometimes remaining viable for centuries.

Consider the process of spore creation in fungi, such as *Aspergillus*. During sporulation, the fungus constructs a spore wall composed of chitin and other polymers, which confers rigidity and resistance to environmental stressors. In plants like ferns, spores develop a wall with layers like the exine and intine, which protect against UV radiation and dehydration. Each layer serves a specific function, demonstrating nature’s precision in engineering survival mechanisms. For practical application, understanding these structures can inform preservation techniques for agricultural seeds or medical sterilization methods targeting spore-forming pathogens.

To illustrate the importance of these layers, compare bacterial spores to fungal spores. Bacterial spores, such as those of *Clostridium botulinum*, have a spore coat and cortex that make them highly resistant to heat and disinfectants, necessitating extreme measures like autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes to ensure destruction. In contrast, fungal spores often rely on thicker cell walls and melanin pigments for protection, which can be less resistant to heat but more resilient to UV light. This comparison highlights how spore structure dictates survival strategies and informs targeted eradication methods.

For those working in fields like microbiology or agriculture, knowing spore structure is crucial. For example, gardeners can enhance seed longevity by storing them in cool, dry conditions (below 10°C and 40% humidity) to mimic the natural dormancy state of spores. Similarly, healthcare professionals must use spore-specific disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide or chlorine compounds to eliminate bacterial spores in medical settings. By leveraging this knowledge, individuals can optimize preservation techniques or develop more effective sterilization protocols, ensuring safety and efficiency in various applications.

In conclusion, the protective layers of spores are not just passive shields but active contributors to their longevity and resilience. From the exosporium’s chemical resistance to the cortex’s structural strength, each layer plays a vital role in safeguarding genetic material. Whether you’re a scientist studying microbial survival or a farmer preserving seeds, understanding these structures empowers you to work with—or against—spores more effectively. This knowledge bridges the gap between theoretical biology and practical problem-solving, offering actionable insights for diverse fields.

Propagating Spore Plants from Cuttings: Is It Possible and How?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In plants, spores are typically created through a process called sporogenesis, which occurs in specialized structures like sporangia. This process involves the division of cells within the sporangium, resulting in the formation of haploid spores. These spores can then develop into new individuals under favorable conditions.

Fungi create spores through various methods, including asexual and sexual reproduction. Asexual spores, such as conidia, are produced by mitosis and can be found on specialized structures like conidiophores. Sexual spores, like asci and basidiospores, are formed through meiosis and are often found in fruiting bodies such as mushrooms and truffles.

Yes, certain bacteria, such as Bacillus and Clostridium species, can create spores through a process called sporulation. This process involves the formation of a protective endospores within the bacterial cell, which allows the bacterium to survive harsh environmental conditions. Sporulation is a complex, multi-step process that involves the replication of DNA, the formation of a spore membrane, and the synthesis of protective layers around the spore.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)