Spores play a crucial role in the life cycle and survival of fungi, serving as their primary means of reproduction and dispersal. These microscopic, single-celled structures are produced in vast quantities and are highly resilient, enabling fungi to withstand harsh environmental conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, and nutrient scarcity. Once released, spores can travel through air, water, or by attaching to animals, eventually landing in new habitats where they germinate under favorable conditions. This dispersal mechanism allows fungi to colonize diverse ecosystems, from soil and decaying matter to living organisms, ensuring their widespread presence and ecological significance. Additionally, spores contribute to the persistence of fungal species over time, acting as a dormant stage that can remain viable for extended periods until conditions are optimal for growth and reproduction.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Role in Reproduction | Spores are the primary means of asexual and sexual reproduction in fungi. They allow fungi to disperse and colonize new environments. |

| Types of Spores | Fungi produce various types of spores, including conidia (asexual spores), sporangiospores (produced in sporangia), zygospores (sexual spores from zygotes), ascospores (from asci in Ascomycetes), and basidiospores (from basidia in Basidiomycetes). |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Spores are dispersed through air, water, animals, or insects. Some fungi use active mechanisms like forcible discharge (e.g., in Pilobolus), while others rely on passive dispersal. |

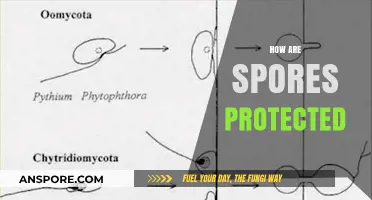

| Dormancy and Survival | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and lack of nutrients. This ensures fungal survival in unfavorable environments. |

| Germination | Under favorable conditions (moisture, nutrients, temperature), spores germinate, producing hyphae that grow into new fungal colonies. |

| Genetic Diversity | Sexual spores (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores) result from genetic recombination, increasing fungal genetic diversity and adaptability. |

| Ecological Importance | Spores play a crucial role in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and symbiotic relationships (e.g., mycorrhizae, lichens). |

| Pathogenicity | Many fungal pathogens (e.g., Aspergillus, Candida) use spores to infect hosts, spreading diseases in plants, animals, and humans. |

| Size and Structure | Spores are typically microscopic (1–100 µm), often single-celled, and may have protective walls (e.g., melanin) to enhance durability. |

| Environmental Impact | Fungal spores are ubiquitous in the environment, contributing to ecosystems as decomposers, pathogens, or mutualistic partners. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation: Fungi produce spores through asexual or sexual reproduction for survival and dispersal

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, animals, and insects aid in spreading fungal spores to new habitats

- Dormancy and Survival: Spores remain dormant in harsh conditions, reviving when the environment becomes favorable

- Germination Process: Spores germinate upon landing in suitable environments, growing into new fungal structures

- Types of Spores: Fungi produce diverse spores (e.g., conidia, zygospores) for different reproductive strategies

Spore Formation: Fungi produce spores through asexual or sexual reproduction for survival and dispersal

Fungi are masters of survival, and their secret weapon is spore formation. These microscopic structures are the result of either asexual or sexual reproduction, each with distinct advantages. Asexual spores, like conidia, are produced rapidly and in vast quantities, ensuring quick colonization of new environments. Sexual spores, such as zygospores and ascospores, combine genetic material from two parents, promoting diversity and adaptability. This dual strategy allows fungi to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from lush forests to arid deserts.

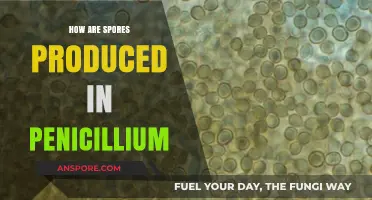

Consider the process of spore formation as a survival toolkit. Asexual reproduction, often triggered by favorable conditions, enables fungi to exploit resources swiftly. For instance, *Penicillium* molds release conidia into the air, which can travel long distances before germinating on suitable substrates. In contrast, sexual reproduction is a more deliberate process, typically occurring under stress or nutrient scarcity. The fusion of gametes in species like *Neurospora* results in hardy spores capable of enduring harsh conditions, such as extreme temperatures or drought. This adaptability underscores the evolutionary brilliance of fungal spore formation.

To understand the practical implications, imagine a gardener battling powdery mildew, a fungal disease caused by asexual spores. These spores can remain dormant on plant debris, only to germinate when conditions are right. To combat this, gardeners should remove infected leaves and apply fungicides preventatively. Conversely, sexual spores, like those of rust fungi, require specific environmental cues to develop, making them less frequent but more resilient. Farmers dealing with rust diseases must monitor weather patterns and crop health to disrupt the sexual spore cycle effectively.

The dispersal mechanisms of spores further highlight their role in fungal survival. Wind, water, and animals act as vectors, carrying spores to new habitats. For example, puffballs release clouds of spores when disturbed, while truffles rely on animals to dig them up and disperse their spores through feces. This diversity in dispersal methods ensures that fungi can colonize even the most inaccessible niches. By studying these mechanisms, scientists can develop strategies to control harmful fungi or harness beneficial ones, such as mycorrhizal fungi that enhance plant growth.

In conclusion, spore formation is not just a reproductive process but a strategic survival mechanism. Whether through rapid asexual proliferation or resilient sexual diversity, fungi leverage spores to endure and expand. Understanding these processes empowers us to manage fungal interactions in agriculture, medicine, and ecology. From the gardener battling mildew to the scientist studying mycorrhizae, the principles of spore formation offer practical insights into the fungal world.

Galactic Adventures: Essential for Spore Mods or Optional Upgrade?

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, animals, and insects aid in spreading fungal spores to new habitats

Fungal spores are nature's hitchhikers, relying on external forces to travel far and wide. Wind, water, animals, and insects serve as their primary dispersal mechanisms, each playing a unique role in transporting spores to new habitats. This process is crucial for fungal survival, colonization, and ecosystem function.

Wind: The Invisible Carrier

Wind dispersal is one of the most common methods for spreading fungal spores. Lightweight and often equipped with structures like wings or threads, spores can be carried over vast distances. For example, the ascospores of *Aspergillus* fungi are easily lofted by air currents, while the basidiospores of mushrooms like *Coprinus comatus* are launched into the wind from their gills. To maximize wind dispersal, fungi often release spores in dry, open environments. Gardeners and farmers should note that windy conditions can exacerbate fungal infections in crops, so monitoring weather patterns and applying fungicides preemptively can mitigate risks.

Water: The Liquid Highway

Water acts as both a transport medium and a habitat for certain fungal spores. Aquatic fungi, such as those in the genus *Achlya*, release spores that float on water surfaces or are carried by currents. Even terrestrial fungi benefit from water dispersal during rain events, as splashing droplets can eject spores from their substrates. For instance, the spores of *Phytophthora*, a water mold responsible for blights like potato late blight, are spread through irrigation systems and rainwater. Homeowners can reduce water-borne fungal spread by ensuring proper drainage and avoiding overwatering plants.

Animals and Insects: Unwitting Couriers

Animals and insects play a dual role in spore dispersal. Some fungi, like the deer truffle (*Elaphomyces*), produce spores that adhere to animal fur or feathers, hitching rides to new locations. Others, such as the insect-pollinated *Ophiocordyceps*, rely on insects to carry spores directly to their hosts. For example, ants infected by *Ophiocordyceps* climb vegetation before dying, releasing spores that can infect other ants below. Gardeners can encourage beneficial insects like bees, which inadvertently carry spores of mycorrhizal fungi, by planting pollinator-friendly flowers.

Practical Takeaways

Understanding these dispersal mechanisms allows for better management of fungal populations. Wind-dispersed spores highlight the need for strategic crop spacing and windbreaks, while water-dispersed spores emphasize the importance of water control. Recognizing the role of animals and insects encourages practices like biodiversity promotion and pest management. By working with these natural processes, we can harness the benefits of fungi while minimizing their negative impacts.

Does E. Coli Form Spores? Unraveling the Bacterial Survival Myth

You may want to see also

Dormancy and Survival: Spores remain dormant in harsh conditions, reviving when the environment becomes favorable

Spores are the ultimate survival capsules of the fungal world, designed to endure conditions that would annihilate most life forms. When faced with extreme temperatures, desiccation, or nutrient scarcity, fungi don't perish—they pause. Spores enter a state of dormancy, a metabolic hibernation that suspends growth and reproduction. This dormancy is not passive; it’s a strategic retreat, a calculated wait for the right moment to reawaken. For example, *Aspergillus* spores can survive temperatures as low as -20°C and as high as 100°C, showcasing their resilience in environments where most organisms would fail.

Consider the desert fungus *Eurotium*, which thrives in arid conditions by producing spores that remain dormant for decades, waiting for the rare rainfall that signals favorable growth conditions. This ability to time their revival is not random but is triggered by specific environmental cues, such as moisture levels, temperature shifts, or nutrient availability. For gardeners or farmers, understanding this mechanism can be practical: fungal spores in soil can remain dormant for years, only to sprout when conditions improve, potentially causing sudden outbreaks of mold or beneficial mycelium, depending on the species.

The dormancy of spores is a marvel of evolutionary engineering, a testament to nature’s ingenuity in ensuring survival against all odds. Unlike seeds, which require specific conditions to germinate, spores are versatile, capable of reviving in a wide range of environments. This adaptability is why fungi are among the first colonizers of barren landscapes, from volcanic ash to post-fire forests. For instance, *Neurospora* spores can revive after exposure to UV radiation, a trait that has made them a subject of study in astrobiology, exploring life’s potential beyond Earth.

To harness this survival strategy, industries are exploring spore dormancy for preservation purposes. In pharmaceuticals, spores of *Bacillus* (a bacterium often studied alongside fungi due to similar spore mechanisms) are used to create probiotics that remain viable for years without refrigeration. Similarly, in agriculture, spore-based biofungicides are applied to crops, lying dormant until pathogens appear, at which point they activate to protect the plants. This application underscores the practical value of understanding spore dormancy, turning a survival mechanism into a tool for human benefit.

In essence, spore dormancy is not just a passive response to adversity but an active strategy that ensures fungal longevity and adaptability. Whether in the lab, the field, or the wild, this mechanism highlights the fungal kingdom’s role as a master of survival, offering lessons in resilience that extend far beyond the microscopic world. By studying and applying these principles, we can unlock new solutions to challenges in conservation, agriculture, and biotechnology, proving that even in dormancy, spores are anything but dormant in their impact.

Bryophytes and Their Spore-Based Life Cycle: Unveiling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination Process: Spores germinate upon landing in suitable environments, growing into new fungal structures

Spores are the microscopic, resilient units fungi use to propagate, akin to seeds in plants. When a spore lands in an environment with adequate moisture, nutrients, and temperature, it initiates germination—a transformative process that bridges dormancy and growth. This activation is not random; it’s a precise response to environmental cues, ensuring the fungus thrives only where survival is likely. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores require water activity above 0.78 to germinate, while *Penicillium* can manage with levels as low as 0.80. Understanding these thresholds is crucial for both harnessing fungi in biotechnology and controlling them in food preservation or medicine.

The germination process begins with the spore absorbing water, swelling, and rupturing its protective coat. This triggers metabolic activity, as stored nutrients like lipids and carbohydrates are mobilized to fuel growth. In *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, germination involves the rapid synthesis of RNA and proteins, preparing the spore to develop into a hyphal structure or yeast cell. Interestingly, some fungi, like *Neurospora crassa*, exhibit a two-stage germination: first, the emergence of a germ tube, followed by its extension into a mycelium. This phased approach ensures resources are allocated efficiently, reducing the risk of premature failure in suboptimal conditions.

From a practical standpoint, controlling spore germination is essential in industries like agriculture and healthcare. For example, farmers use fungicides targeting spore germination to prevent crop diseases, while bakers exploit yeast spore germination to leaven bread. In medicine, antifungal drugs like fluconazole disrupt the germination process by inhibiting ergosterol synthesis in fungal cell membranes. Conversely, researchers in mycoremediation encourage spore germination in polluted soils, leveraging fungi’s ability to degrade toxins. Each application hinges on manipulating the environmental factors that trigger germination, underscoring its central role in fungal ecology and human endeavors.

Comparatively, spore germination in fungi is more adaptable than seed germination in plants. While plant seeds often require specific light or temperature signals, fungal spores can germinate in complete darkness and across a broader temperature range. This flexibility reflects fungi’s evolutionary success in colonizing diverse habitats, from deep-sea vents to arid deserts. For instance, *Xeromyces bisporus* spores germinate in environments with as little as 0.61 water activity, enabling them to thrive in dried foods. Such adaptability highlights why fungi are both a challenge to control and a resource to exploit, depending on the context.

In conclusion, the germination of fungal spores is a finely tuned process that balances survival and proliferation. By responding to environmental cues with precision, spores ensure fungi colonize only the most favorable niches. Whether viewed through the lens of biology, industry, or ecology, this process exemplifies fungi’s resilience and versatility. For anyone working with fungi—whether combating pathogens or cultivating mushrooms—mastering the dynamics of spore germination is key to success. After all, it’s not just about growth; it’s about strategic growth in the right place at the right time.

Effective Mold Removal: Clean Safely Without Spreading Spores

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Fungi produce diverse spores (e.g., conidia, zygospores) for different reproductive strategies

Fungi are masters of survival, and their reproductive strategies reflect this adaptability. Central to their success are spores, specialized cells designed for dispersal and dormancy. However, not all spores are created equal. Fungi produce a diverse array of spore types, each tailored to specific environmental conditions and reproductive goals. Understanding these variations sheds light on the remarkable versatility of fungal life cycles.

For instance, conidia are asexual spores produced at the ends of specialized hyphae. These spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or insects, allowing fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* to colonize new environments rapidly. Their production is a quick and efficient means of reproduction, ideal for exploiting transient nutrient sources. In contrast, zygospores are the product of sexual reproduction, formed when two compatible hyphae fuse. These thick-walled spores, characteristic of zygomycetes, are highly resistant to harsh conditions, enabling them to survive in extreme environments until favorable conditions return. This duality—rapid asexual reproduction versus resilient sexual spores—highlights the strategic diversity of fungal spore types.

Consider the ascospores of sac fungi (Ascomycota), which are produced within sac-like structures called asci. These spores are ejected forcefully, a mechanism that ensures widespread dispersal. This method is particularly effective in environments where wind is a dominant force, such as forests or open fields. Similarly, basidiospores, produced by club fungi (Basidiomycota), are borne on specialized structures called basidia. These spores are often associated with mushrooms and play a critical role in decomposing organic matter. Each spore type is not just a means of reproduction but a solution to specific ecological challenges, whether it’s rapid colonization, long-term survival, or efficient dispersal.

Practical applications of this knowledge are vast. For example, in agriculture, understanding conidia production in *Trichoderma* species can inform the development of biocontrol agents to combat plant pathogens. Conversely, the resilience of zygospores explains why certain fungi persist in soil for decades, a factor to consider in crop rotation strategies. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, recognizing the role of basidiospores in fruiting body formation can optimize growing conditions. Even in medicine, the study of fungal spores helps in diagnosing infections, as different spore types may indicate specific fungal pathogens.

A comparative analysis reveals that spore types are not just adaptations but evolutionary innovations. While conidia and basidiospores prioritize dispersal and rapid growth, zygospores and ascospores emphasize survival under stress. This diversity ensures that fungi can thrive in virtually every ecosystem on Earth, from the Arctic to tropical rainforests. For instance, the black mold *Stachybotrys* produces conidia that thrive in damp indoor environments, while the desert fungus *Eurotium* relies on ascospores to endure arid conditions. Such examples underscore the importance of spore diversity in fungal ecology.

In conclusion, the variety of fungal spores is a testament to the ingenuity of nature. Each spore type—conidia, zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores—serves a unique purpose, reflecting the fungus’s reproductive strategy and environmental niche. By studying these differences, we gain insights into fungal biology, improve agricultural practices, and address health challenges. Whether you’re a scientist, farmer, or enthusiast, understanding spore types is key to unlocking the secrets of the fungal kingdom.

Can Dish Soap Effectively Kill Mold Spores? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungi produce spores through specialized structures like sporangia, basidia, or asci, depending on the fungal group. Spores are formed via asexual (mitosis) or sexual (meiosis) reproduction, allowing fungi to disperse and survive in various environments.

Spores serve as a dormant, resistant form that helps fungi survive harsh conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, or lack of nutrients. Once conditions improve, spores germinate and grow into new fungal individuals.

Fungal spores are dispersed through air, water, animals, or insects. Some fungi use wind to carry lightweight spores, while others rely on water splashes or animal contact. This dispersal mechanism ensures fungi colonize new habitats and spread widely.