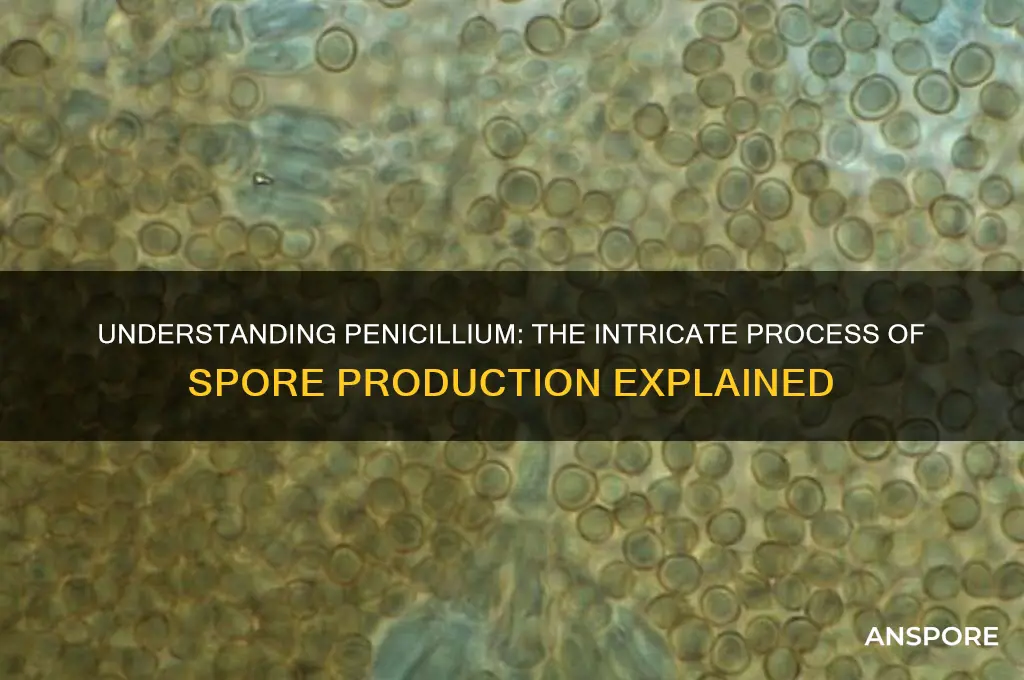

Penicillium, a genus of ascomycetous fungi, produces spores through a specialized reproductive process essential for its life cycle and dispersal. The production of spores in Penicillium occurs primarily via asexual means, through structures called conidiophores. These conidiophores are long, filamentous structures that develop from the vegetative mycelium and bear chains or clusters of asexual spores known as conidia. Conidia are typically unicellular, non-motile, and encased in a protective wall, allowing them to survive harsh environmental conditions. The formation of conidiophores and conidia is influenced by environmental factors such as light, temperature, and nutrient availability. Once mature, the conidia are released into the environment, where they can disperse through air currents, water, or other vectors, enabling the fungus to colonize new habitats and propagate its species. This efficient spore production mechanism is a key factor in the widespread distribution and ecological success of Penicillium.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sporulation Process | Asexual reproduction via conidiogenesis (formation of conidia/spores). |

| Structure Involved | Penicilli (brush-like structures) on the apex of conidiophores. |

| Conidiophore Development | Arises from vegetative hyphae, elongates, and branches. |

| Phialides Formation | Sterile branches (metulae) produce phialides (spore-bearing cells). |

| Conidia Production | Phialides produce conidia (spores) in basipetal succession. |

| Conidia Characteristics | Unicellular, dry, and easily dispersed by air currents. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Conidia are released into the air for dissemination. |

| Environmental Triggers | Sporulation is influenced by nutrient depletion and environmental cues. |

| Genetic Regulation | Controlled by genes like brlA (initiates sporulation). |

| Ecological Role | Aids in survival, dispersal, and colonization of new habitats. |

Explore related products

$9.25 $11.99

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation initiation: Environmental triggers like nutrient depletion or stress activate sporulation genes in Penicillium

- Conidiophore development: Specialized hyphae grow vertically, forming structures for spore production

- Phialide formation: Conidiophores branch into phialides, the spore-producing cells

- Conidiospore creation: Phialides produce chains of asexual spores (conidia) via budding or blastic processes

- Spore maturation & release: Conidia mature, dry out, and disperse via air currents for colonization

Sporulation initiation: Environmental triggers like nutrient depletion or stress activate sporulation genes in Penicillium

Penicillium, a genus of fungi renowned for its role in antibiotic production, initiates sporulation in response to specific environmental cues. When nutrients become scarce, the fungus detects this depletion through intricate signaling pathways. For instance, nitrogen limitation triggers the activation of the LaeA gene, a global regulator of secondary metabolism and sporulation. This gene acts as a molecular switch, redirecting the fungus’s energy from vegetative growth to reproductive structures. Similarly, carbon starvation induces the expression of BrlA, a key transcription factor that initiates the developmental cascade leading to spore formation. These genetic responses are finely tuned, ensuring survival in adverse conditions.

Stress, another potent trigger, accelerates sporulation in Penicillium. Oxidative stress, caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS), activates stress-responsive genes like Skn7, which in turn upregulates sporulation pathways. Temperature fluctuations, particularly shifts to lower temperatures (e.g., 20–25°C), also stimulate spore development. For example, in *Penicillium chrysogenum*, exposure to mild heat stress (37°C for 2 hours) enhances conidiation by promoting the accumulation of VelB, a protein essential for spore morphogenesis. These stress-induced mechanisms highlight the fungus’s adaptability, transforming adversity into a reproductive opportunity.

Understanding these triggers has practical implications for optimizing spore production in industrial settings. To induce sporulation in Penicillium cultures, researchers often manipulate nutrient availability by reducing nitrogen levels to 0.05% (w/v) in the growth medium. Additionally, controlled exposure to mild stressors, such as 10 mM hydrogen peroxide for 30 minutes, can mimic oxidative stress and accelerate spore formation. However, caution is advised: excessive stress or nutrient deprivation can lead to cellular damage or dormancy. Balancing these factors is critical for maximizing yield without compromising fungal health.

Comparatively, Penicillium’s sporulation response contrasts with that of bacteria, which often form endospores under stress. While bacterial endospores are highly resistant and dormant, Penicillium spores remain metabolically active, ready to germinate when conditions improve. This distinction underscores the fungus’s strategy: prioritizing rapid dispersal over long-term survival. By leveraging environmental cues, Penicillium ensures its persistence in dynamic ecosystems, making it a fascinating subject for both biological research and biotechnological applications.

Can Spores Contaminate Your Grow? Prevention and Solutions Explained

You may want to see also

Conidiophore development: Specialized hyphae grow vertically, forming structures for spore production

Specialized hyphae in *Penicillium* species undergo a remarkable transformation to facilitate spore production, a process pivotal for the fungus's survival and dissemination. These hyphae, known as conidiophores, are the architectural marvels behind the fungus's reproductive strategy. Imagine a microscopic construction project where these cellular structures grow vertically, reaching towards the air, to create a platform for spore development. This vertical growth is not merely a random occurrence but a highly regulated process, ensuring the efficient production and dispersal of spores.

The development of conidiophores is a multi-step journey. It begins with the initiation of specialized cells, which then elongate and branch, forming a complex network. This growth is not haphazard; it follows a precise pattern, with each branch contributing to the overall structure. As the conidiophore matures, it becomes a towering edifice, often with multiple levels or stories, each bearing spore-producing cells. This vertical arrangement is strategic, allowing for the optimal release of spores into the surrounding environment.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Conidiophore Construction:

- Initiation: The process starts with the activation of specific genes, triggering the transformation of ordinary hyphae into conidiophore-forming cells.

- Elongation: These cells rapidly grow in length, pushing upwards, defying the typical horizontal growth pattern of hyphae.

- Branching: As the structure ascends, it branches out, creating a tree-like framework. Each branch is a potential site for spore formation.

- Spore Production: At the tips of these branches, spores, known as conidia, develop. These spores are the fungus's offspring, ready to be dispersed.

The vertical growth of conidiophores is a critical adaptation, ensuring that spores are elevated, increasing their chances of being carried away by air currents. This strategy is particularly effective in *Penicillium*, allowing it to colonize new environments and survive in various conditions. For instance, in a laboratory setting, understanding this process is crucial for culturing and studying the fungus, where controlled conditions can mimic its natural habitat, promoting conidiophore development and spore collection for research.

In the world of fungi, *Penicillium* stands out for its efficient spore production, thanks to the intricate development of conidiophores. This process, a blend of cellular growth and architectural precision, showcases the fungus's ability to thrive and adapt. By studying these specialized structures, scientists gain insights into fungal biology, with potential applications in biotechnology and medicine, where spore production is a key area of interest.

Are Spores Genetically Identical? Exploring the Science Behind Spore Diversity

You may want to see also

Phialide formation: Conidiophores branch into phialides, the spore-producing cells

Penicillium, a genus of fungi renowned for its role in antibiotic production, employs a sophisticated mechanism for spore dispersal. Central to this process is the formation of phialides, specialized cells that emerge from conidiophores, the fungal structures responsible for asexual reproduction. This intricate branching system is a marvel of microbial engineering, optimizing spore production and release.

The Phialide Factory: A Microscopic Assembly Line

Imagine a tree-like structure, but on a microscopic scale. The conidiophore, akin to the trunk, branches out into smaller structures called metulae, which further divide into phialides. These phialides, resembling tiny flasks, are the spore-producing powerhouses. Within each phialide, a single spore, known as a conidium, develops. This assembly line-like process ensures a high yield of spores, crucial for the fungus's survival and propagation.

A Delicate Balance: Factors Influencing Phialide Development

The formation of phialides is a finely tuned process, influenced by various environmental cues. Optimal conditions, including temperature, humidity, and nutrient availability, are essential for conidiophore growth and subsequent phialide development. For instance, Penicillium species often thrive in environments with temperatures ranging from 20°C to 28°C and relative humidity levels above 70%. Deviations from these conditions can hinder phialide formation, impacting spore production.

The Art of Spore Release: A Mechanical Marvel

Once mature, the conidia are ready for dispersal. The phialides play a critical role in this stage, employing a unique mechanism for spore release. As the conidium develops within the phialide, it accumulates turgor pressure, eventually leading to its forceful ejection. This process, known as 'ballistic spore discharge,' can propel spores over short distances, increasing the chances of colonization in new environments.

Practical Implications: Harnessing Phialide Formation

Understanding phialide formation has practical applications, particularly in the production of penicillin. By optimizing growth conditions to enhance conidiophore development and phialide formation, pharmaceutical manufacturers can increase the yield of penicillin-producing Penicillium strains. This knowledge also aids in the development of strategies to control fungal growth in various industries, such as food production and agriculture, where fungal contamination can be detrimental.

In summary, phialide formation is a critical aspect of Penicillium's life cycle, showcasing the fungus's remarkable adaptability and efficiency. From the intricate branching of conidiophores to the precise mechanics of spore release, this process is a testament to the complexity of microbial life. By studying and harnessing these mechanisms, we can unlock new possibilities in medicine, industry, and our understanding of the natural world.

Can Rubbing Alcohol Effectively Kill Bacterial Spores? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Conidiospore creation: Phialides produce chains of asexual spores (conidia) via budding or blastic processes

Penicillium, a genus of fungi renowned for its role in antibiotic production, employs a fascinating mechanism for spore creation. At the heart of this process lies the phialide, a specialized cell that serves as the factory for conidiospores, the asexual spores of Penicillium. These phialides are not merely passive producers; they are dynamic structures that generate spores through either budding or blastic processes, each method contributing to the fungus’s prolific reproductive strategy.

To visualize this, imagine a microscopic assembly line. Phialides, often flask-shaped, extend from the fungus’s conidiophores (spore-bearing structures). Within each phialide, a spore begins to form at the tip, either by budding, where the spore gradually emerges as an outgrowth, or through a blastic process, where the spore is forcibly ejected. This distinction is crucial: budding results in spores that remain attached in chains, while blastic processes often produce spores that are more immediately dispersed. Both methods ensure that Penicillium can efficiently colonize new environments, a key survival trait for this ubiquitous fungus.

For those cultivating Penicillium in laboratory settings, understanding this process is essential. Optimal conditions for conidiospore production include a temperature range of 20–25°C and a relative humidity of 80–90%. Researchers often use nutrient-rich agar plates supplemented with glucose to encourage conidiophore development. A practical tip: gently agitating the culture can enhance spore release, mimicking natural dispersal mechanisms. However, caution must be exercised to avoid contamination, as Penicillium’s rapid growth can outcompete other microorganisms but also risks overrunning the medium.

Comparatively, the conidiospore creation in Penicillium contrasts with the spore production of other fungi, such as those forming zygospores or basidiospores, which involve sexual reproduction. Penicillium’s reliance on asexual spores highlights its adaptability and efficiency in diverse environments, from soil to decaying organic matter. This asexual strategy allows for rapid proliferation, a trait exploited in industrial applications like antibiotic production, where consistent and abundant spore formation is critical.

In conclusion, the role of phialides in conidiospore creation is a testament to Penicillium’s evolutionary ingenuity. By mastering the budding and blastic processes, this fungus ensures its survival and dominance in various ecosystems. Whether you’re a mycologist, a biotechnologist, or simply curious about fungal biology, appreciating this mechanism provides insights into both natural processes and practical applications, from medicine to agriculture.

Hydrogen Peroxide's Effectiveness Against C. Diff Spores: What Research Shows

You may want to see also

Spore maturation & release: Conidia mature, dry out, and disperse via air currents for colonization

Penicillium, a genus of fungi renowned for its role in antibiotic production, employs a sophisticated process to ensure the survival and dispersal of its offspring. The final stage of this reproductive journey is the maturation and release of conidia, the asexual spores that serve as the primary agents of colonization. This phase is a delicate balance of physiological changes and environmental cues, culminating in the liberation of spores ready to embark on new adventures.

As conidia mature, they undergo a series of transformations that prepare them for life outside the protective confines of the fungal colony. The initial pliable, hydrated state gives way to a more robust, desiccated form, a process akin to a caterpillar metamorphosing into a butterfly. This drying out is not merely a passive event but an active, energy-demanding process, where the fungus invests resources to ensure the spores' viability. The conidia's cell walls thicken, and their internal structures reorganize, creating a resilient shell capable of withstanding the rigors of the external environment.

The maturation process is a critical juncture, as it determines the spores' ability to survive and germinate upon reaching a suitable substrate. Imagine a fleet of tiny, airborne vessels, each equipped with the necessary provisions for a successful journey. These provisions include stored nutrients, protective pigments, and enzymes that enable the spores to recognize and respond to environmental signals. The fungus, in its wisdom, equips each conidium with a unique toolkit, tailored to the challenges it might encounter during its aerial voyage.

Once mature, the conidia are ready for their grand departure. The fungus, ever the strategic disperser, times this release to coincide with optimal conditions for dispersal. As air currents caress the fungal colony, the dry, lightweight conidia are dislodged, rising like a cloud of microscopic balloons. This aerial dispersal is a numbers game, with millions of spores released to increase the odds of successful colonization. The fungus, in essence, employs a shotgun approach, scattering its offspring far and wide, trusting that some will find fertile ground.

In practical terms, understanding this maturation and release process has implications for various fields. For instance, in agriculture, knowing the conditions that favor conidia dispersal can inform strategies to manage fungal pathogens. In biotechnology, manipulating the maturation process could enhance the production of valuable compounds, such as penicillin. Moreover, for enthusiasts cultivating Penicillium species, providing adequate air circulation and humidity control during the maturation phase can optimize spore production, ensuring a bountiful harvest for experimentation or educational purposes. This intricate dance of maturation and release is not just a biological curiosity but a key to unlocking the potential of these remarkable fungi.

Psilocybin Spores in Puerto Rico: Legal Status Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Penicillium produces spores through a process called sporulation, which involves the formation of asexual spores known as conidia. This process occurs on specialized structures called conidiophores.

Spores in Penicillium develop at the tips of conidiophores, which are filamentous structures that grow from the mycelium. The conidia form in chains or clusters at the ends of these structures.

Conidia are formed through a series of cell divisions at the tip of the conidiophore. The cells produced are initially undifferentiated but eventually develop into mature spores, which are then released into the environment.

Spore production in Penicillium is typically triggered by environmental factors such as nutrient depletion, changes in light, temperature, or humidity. These conditions signal the fungus to enter the sporulation phase to ensure survival and dispersal.