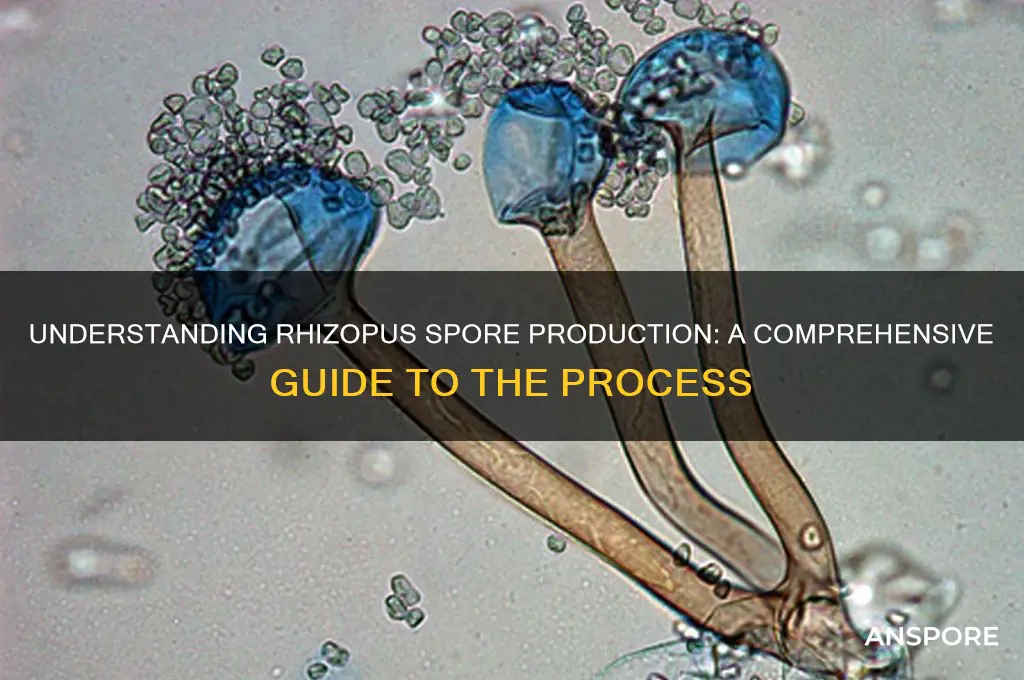

Rhizopus, a common mold belonging to the Zygomycota phylum, produces spores through a specialized reproductive process. Unlike many other fungi, Rhizopus does not form complex fruiting bodies but instead relies on sporangia, which are spherical structures located at the tips of specialized hyphae called sporangiophores. Within these sporangia, haploid spores called sporangiospores are produced through mitosis. The sporangium wall eventually ruptures, releasing the spores into the environment, where they can disperse and germinate under favorable conditions to form new mycelia. This asexual reproductive strategy allows Rhizopus to rapidly colonize substrates and thrive in diverse environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sporangiospore Formation | Spores are produced inside a spherical structure called a sporangium. |

| Sporangiophore Development | A specialized hyphal stalk called a sporangiophore grows from the mycelium. |

| Sporangium Formation | The sporangium develops at the tip of the sporangiophore. |

| Meiosis | Spores are typically haploid, formed via meiosis in the sporangium. |

| Maturation | The sporangium matures, filling with numerous sporangiospores. |

| Release Mechanism | The sporangium wall ruptures, releasing the spores into the environment. |

| Dispersal | Spores are dispersed by air currents, water, or other agents. |

| Germination | Spores can germinate under favorable conditions to form new mycelium. |

| Asexual Reproduction | The process is asexual, as spores are produced without fertilization. |

| Environmental Triggers | Sporulation is often triggered by nutrient depletion or environmental stress. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporangiospore formation process

Sporangiospore formation in *Rhizopus* is a fascinating process that begins with the maturation of a sporangium, a spherical structure at the tip of a specialized hyphal branch called a sporangiophore. This process is triggered under favorable conditions, such as nutrient depletion or environmental stress, prompting the fungus to transition from vegetative growth to reproductive mode. Inside the sporangium, haploid nuclei undergo mitosis, producing numerous nuclei that migrate to the periphery of the structure. Concurrently, the cytoplasm differentiates into discrete protoplasts, each containing a single nucleus. These protoplasts then develop cell walls, transforming into sporangiospores—the primary means of asexual reproduction in *Rhizopus*.

The formation of sporangiospores is a highly coordinated event, involving both nuclear division and cytoplasmic partitioning. As the sporangium matures, its wall becomes thin and translucent, allowing the spores to be easily dispersed upon rupture. This dispersal mechanism is often facilitated by air currents, insects, or other environmental factors, ensuring the widespread distribution of the fungus. Notably, the sporangiospores are multicellular and remain enclosed within the sporangium until it bursts, a process that can be hastened by mechanical disturbance or desiccation. This protective enclosure enhances the spores' survival in adverse conditions, a critical adaptation for a saprophytic organism like *Rhizopus*.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporangiospore formation is essential for controlling *Rhizopus* growth in agricultural and industrial settings. For instance, in bread molds caused by *Rhizopus*, the sporangia and sporangiospores are the primary culprits of contamination. To mitigate this, maintaining low humidity (below 60%) and temperatures below 20°C can inhibit sporangium development. Additionally, regular cleaning of surfaces with fungicides or natural agents like vinegar can disrupt the spore formation process. For laboratory cultures, researchers often manipulate nutrient availability to induce or suppress sporangiospore production, providing insights into the fungus's life cycle.

Comparatively, sporangiospore formation in *Rhizopus* differs from other fungal reproductive strategies, such as conidia production in *Aspergillus* or zygospore formation in zygomycetes. Unlike conidia, which are unicellular and produced directly on conidiophores, sporangiospores are multicellular and enclosed within a sporangium. This distinction highlights the evolutionary adaptations of *Rhizopus* to its ecological niche, favoring rapid dispersal and colonization of nutrient-rich substrates. By studying these differences, scientists can develop targeted strategies to manage fungal growth in various contexts, from food preservation to medical mycology.

In conclusion, the sporangiospore formation process in *Rhizopus* is a remarkable example of fungal reproductive efficiency. From the initial nuclear divisions to the final dispersal of spores, each step is finely tuned to ensure survival and propagation. Whether you're a researcher, farmer, or simply curious about fungi, understanding this process provides valuable insights into the biology of *Rhizopus* and practical tools for managing its impact. By focusing on the specifics of sporangiospore formation, we can appreciate the elegance of nature's design and apply this knowledge to real-world challenges.

Does Bleach Kill Bacterial Spores? Uncovering the Truth Behind Disinfection

You may want to see also

Role of sporangiophores in spore development

Sporangiophores in *Rhizopus* are not merely structural appendages but specialized aerial hyphae that serve as the cradle for spore development. These erect, multinucleated structures emerge from the mycelium, ascending towards the air to maximize spore dispersal. Their primary function is to support sporangia—the sac-like structures where spores are produced. Without sporangiophores, spores would remain trapped within the substrate, limiting the fungus’s ability to colonize new environments. This vertical growth is a strategic adaptation, ensuring that spores are released into air currents for efficient dissemination.

The development of sporangiophores is a tightly regulated process, triggered by environmental cues such as nutrient depletion, light exposure, and humidity changes. Once initiated, the hyphal tip elongates rapidly, forming a sporangiophore that can reach several millimeters in height. At its apex, a globular sporangium develops, within which hundreds to thousands of spores are generated through mitotic divisions. The sporangium’s wall is thin and delicate, designed to rupture upon maturity, releasing the spores into the environment. This synchronized growth and spore production highlight the sporangiophore’s role as both a structural and functional linchpin in *Rhizopus* reproduction.

To visualize the sporangiophore’s role, consider it a biological scaffold—a temporary yet essential structure that facilitates spore maturation and dispersal. Its walls are enriched with enzymes and structural proteins that support the sporangium’s development while remaining flexible enough to allow spore release. For instance, the sporangium’s outer layer often contains chitinases that weaken the wall just before spore dispersal, ensuring a timely and efficient release. This precision in structure and function underscores the sporangiophore’s critical role in the fungal life cycle.

Practical observations of sporangiophores in *Rhizopus* can be made by culturing the fungus on bread or agar plates. Within 24–48 hours, sporangiophores become visible as white, tower-like structures, with sporangia appearing as dark dots at their tips. To study spore release, gently tap the culture or expose it to air currents, and observe the cloud of spores dispersing. This simple experiment illustrates the sporangiophore’s role in elevating spores above the substrate, a key adaptation for airborne dispersal. For educational purposes, time-lapse photography can capture the dynamic growth of sporangiophores, providing a vivid demonstration of their function in spore development.

In summary, sporangiophores are indispensable for *Rhizopus* spore development, acting as both a physical support and a developmental hub. Their strategic growth ensures spores are positioned for optimal dispersal, while their structural adaptations facilitate timely release. Understanding their role not only sheds light on fungal reproduction but also offers insights into controlling *Rhizopus* in food spoilage or harnessing it in biotechnological applications. By focusing on sporangiophores, we gain a deeper appreciation for the elegance and efficiency of fungal reproductive strategies.

Are All Psilocybe Spore Prints Purple? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for spore production

Spores in *Rhizopus*, a common zygomycete fungus, are not merely products of random development but are finely tuned responses to environmental cues. These cues act as triggers, signaling the fungus to initiate sporulation—a critical survival strategy. Among the most potent environmental triggers is nutrient deprivation. When *Rhizopus* exhausts available resources, such as carbon or nitrogen, it shifts from vegetative growth to reproductive mode, producing sporangiospores as a means to disperse and seek new habitats. This response is not just a passive reaction but a highly regulated process, demonstrating the fungus’s adaptability to fluctuating conditions.

Light exposure plays a surprisingly significant role in spore production, though its influence is often overlooked. Studies show that *Rhizopus* exposed to specific wavelengths of light, particularly in the blue spectrum (450–495 nm), accelerates sporulation. This phenomenon is thought to mimic natural daylight cycles, prompting the fungus to prepare for dispersal during optimal conditions. Conversely, prolonged darkness can delay spore formation, highlighting the importance of light as a temporal cue. For cultivators or researchers, manipulating light exposure—such as using LED lights with blue wavelengths for 12–16 hours daily—can enhance spore yield in controlled environments.

Temperature fluctuations act as another critical trigger, with *Rhizopus* favoring a narrow range for sporulation. Optimal temperatures for spore production typically fall between 25°C and 30°C, mirroring the fungus’s preference for warm, humid environments. Below 20°C, sporulation slows significantly, while temperatures above 35°C can inhibit the process altogether. This sensitivity to temperature underscores the fungus’s ecological niche and explains its prevalence in tropical and subtropical regions. Practical applications include maintaining consistent temperatures in laboratory settings to ensure predictable spore development.

Humidity levels are equally vital, as *Rhizopus* thrives in environments with relative humidity above 80%. Dry conditions hinder spore formation, while high humidity facilitates the maturation and release of sporangiospores. This is particularly evident in natural settings, where *Rhizopus* often colonizes decaying organic matter with high moisture content. For artificial cultivation, using humidifiers or sealed chambers can replicate these conditions, ensuring robust spore production. However, excessive moisture can lead to contamination, so balancing humidity with adequate ventilation is crucial.

Finally, pH levels in the substrate can either promote or inhibit sporulation in *Rhizopus*. The fungus prefers a slightly acidic to neutral environment, with optimal sporulation occurring at pH 5.5–7.0. Deviations from this range, particularly toward alkalinity, can disrupt the process. Adjusting pH levels in growth media—using buffers like phosphate or citrate—can optimize conditions for spore production. This precision in environmental control not only enhances laboratory studies but also improves industrial applications, such as enzyme production or biomass cultivation, where *Rhizopus* spores are the starting point.

Wireless Printing on a Hot Spot: Tips and Tricks for Success

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Maturation and release mechanisms

Spores in *Rhizopus*, a common zygomycete fungus, mature and are released through a highly coordinated process that ensures their viability and dispersal. The maturation phase begins with the formation of sporangia, the structures that house the spores. Within these sporangia, sporocytes undergo multiple rounds of division, ultimately producing hundreds to thousands of haploid spores. This process is tightly regulated by environmental cues, such as nutrient availability and humidity, which signal the fungus to prepare for the next life cycle stage.

The release mechanism of *Rhizopus* spores is both efficient and adaptive. As the sporangia mature, the sporangial wall undergoes enzymatic degradation, weakening its structure. This degradation is triggered by the accumulation of mature spores within, creating internal pressure. When conditions are optimal—typically in the presence of air movement or physical disturbance—the sporangial wall ruptures, releasing the spores into the environment. This explosive release ensures widespread dispersal, increasing the chances of colonization in new habitats.

A key factor in spore release is the role of air currents. *Rhizopus* spores are lightweight and easily carried by even gentle breezes, a trait that maximizes their dispersal range. To enhance this process, the fungus often grows in exposed areas, such as on decaying organic matter, where air movement is more likely. For those studying or working with *Rhizopus*, mimicking these conditions—for example, by using a fan in laboratory settings—can facilitate spore collection or experimentation.

Comparatively, the maturation and release mechanisms of *Rhizopus* spores differ from those of other fungi, such as *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, which rely on more gradual release processes. *Rhizopus*’s explosive dispersal is particularly effective in its ecological niche, where rapid colonization of nutrient-rich substrates is essential. This distinction highlights the evolutionary adaptation of *Rhizopus* to its environment, emphasizing the importance of understanding these mechanisms in both biological research and practical applications, such as food spoilage prevention.

In practical terms, controlling spore maturation and release in *Rhizopus* can be crucial in industries like food production, where the fungus is a common contaminant. Maintaining low humidity and minimizing air disturbance in storage areas can inhibit sporangial rupture, reducing the risk of spore dispersal. Additionally, understanding the enzymatic processes involved in sporangial wall degradation opens avenues for developing targeted antifungal agents. By disrupting these mechanisms, it may be possible to prevent spore release and limit fungal growth, offering a novel approach to fungal control.

Patching Galactic Adventures: Essential for Modding Spore or Optional?

You may want to see also

Genetic control of sporulation in Rhizopus

Sporulation in *Rhizopus*, a key process for its survival and dispersal, is tightly regulated by genetic mechanisms. At the heart of this regulation lies the *spo* gene cluster, a set of genes that orchestrate the developmental transition from vegetative growth to spore formation. These genes encode transcription factors, enzymes, and structural proteins essential for spore wall synthesis, maturation, and dormancy. For instance, the *spoK* gene, a central regulator, activates downstream genes like *spsA* and *spsB*, which are involved in spore wall biogenesis. Mutations in these genes often result in sporulation defects, highlighting their critical role in the process.

Understanding the genetic control of sporulation in *Rhizopus* requires a comparative approach. Unlike *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, where sporulation is triggered by nutrient deprivation, *Rhizopus* sporulates in response to environmental cues such as pH changes, light exposure, and surface sensing. This divergence underscores the unique genetic circuitry evolved in *Rhizopus*. For example, the *ras* signaling pathway, which is conserved across fungi, plays a distinct role in *Rhizopus* by integrating environmental signals to activate sporulation genes. This pathway’s sensitivity to external conditions, such as a pH shift from 7.0 to 4.5, triggers a cascade of gene expression leading to spore formation.

Practical applications of this genetic control are emerging in biotechnology. By manipulating sporulation genes, researchers can enhance spore yield in *Rhizopus* strains used for enzyme production or fermentation. For instance, overexpression of the *spoK* gene has been shown to increase spore production by up to 40% in controlled conditions. However, caution is advised when altering these genes, as unintended mutations can disrupt other cellular processes. A step-by-step approach involves: (1) identifying target genes using RNA-seq data, (2) constructing overexpression or knockout strains via CRISPR-Cas9, and (3) optimizing growth conditions (e.g., 28°C, pH 4.5) to maximize sporulation efficiency.

A descriptive analysis of the sporulation process reveals its elegance and complexity. As hyphae sense environmental cues, nuclei undergo mitosis, and septa form to compartmentalize cells. The *spo* genes then activate, directing the synthesis of a thick, melanized spore wall. This wall provides resistance to UV radiation, desiccation, and predators, ensuring spore longevity. Microscopic observation shows that mature spores are typically 5–10 μm in diameter, with a distinct dark pigmentation. This morphological transformation is a testament to the precision of genetic control, where each step is finely tuned to produce viable, resilient spores.

In conclusion, the genetic control of sporulation in *Rhizopus* is a fascinating interplay of environmental sensing and gene regulation. By studying this process, scientists can unlock new biotechnological applications and gain insights into fungal development. Whether for industrial spore production or fundamental research, understanding the *spo* gene cluster and its regulatory pathways is essential. Practical tips, such as monitoring pH and temperature, can significantly enhance sporulation efficiency, making this knowledge both scientifically intriguing and industrially valuable.

Understanding the Meaning and Usage of 'Spor' in Language and Culture

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Rhizopus produces spores through a process called sporulation, which involves the development of sporangiospores within a sporangium at the tip of a sporangiophore.

Spores in Rhizopus form inside a structure called the sporangium, which is located at the end of a long, erect structure known as the sporangiophore.

Rhizopus produces asexual spores called sporangiospores, which are formed through mitosis and are typically multicellular and haploid.

Sporangiophores in Rhizopus are produced from the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, in response to environmental cues such as nutrient availability and humidity.

Yes, under certain conditions, Rhizopus can produce sexual spores called zygospores through a process called zygosporation, which involves the fusion of two compatible hyphae to form a thick-walled zygospore.