Spores in yeast cultures are created through a specialized reproductive process known as sporulation, which is triggered in response to environmental stresses such as nutrient depletion. During sporulation, a diploid yeast cell undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid nuclei, which then develop into spores within a protective ascus. This process involves intricate cellular reorganization, including the formation of prospore membranes and the assembly of spore walls, ensuring the spores are resilient to harsh conditions. Sporulation is crucial for yeast survival, as spores can remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions return, allowing them to germinate and resume vegetative growth. This mechanism highlights yeast's adaptability and is widely studied for its biological and biotechnological significance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Name | Sporulation or Ascospore Formation |

| Yeast Type | Primarily observed in Ascomycetes (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae) |

| Trigger Conditions | Nutrient depletion (e.g., nitrogen starvation), high cell density |

| Cell Type Involved | Diploid yeast cells (haploid cells cannot sporulate) |

| Meiosis Occurrence | Yes, involves meiosis I and II to produce 4 haploid spores |

| Spore Wall Composition | Thick, multilayered (inner prosoptect, outer episporon, exospore) |

| Spore Resistance | Highly resistant to heat, desiccation, and chemicals |

| Timeframe | 5–10 days under optimal conditions |

| Genetic Regulation | Controlled by IME1 gene and SPO genes |

| Environmental Factors | Requires non-fermentable carbon sources (e.g., acetate) |

| Spore Function | Survival in harsh conditions; genetic diversity via mating |

| Spore Release | Ascospore release occurs via ascus rupture (mechanical or enzymatic) |

| Applications | Used in biotechnology, food industry (e.g., brewing), and research |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation initiation conditions: Nutrient depletion, pH changes, and environmental stressors trigger yeast to enter sporulation

- Meiosis process: Yeast undergoes meiosis, reducing chromosome number, essential for spore formation

- Ascus development: Spores develop within an ascus, a protective sac formed during sporulation

- Spore wall formation: Layers of mannoproteins and chitin create a durable spore wall

- Maturation and release: Spores mature, dehydrate, and are released when the ascus ruptures

Sporulation initiation conditions: Nutrient depletion, pH changes, and environmental stressors trigger yeast to enter sporulation

Yeast, a eukaryotic microorganism, employs sporulation as a survival strategy in response to adverse environmental conditions. This process, akin to a microbial hibernation, involves the formation of resilient spores capable of enduring harsh conditions until more favorable circumstances arise. The initiation of sporulation is a complex and tightly regulated process, primarily triggered by three key factors: nutrient depletion, pH changes, and environmental stressors.

Nutrient Depletion: A Critical Signal

The availability of nutrients, particularly nitrogen, plays a pivotal role in yeast sporulation. When nitrogen levels in the culture medium drop below a certain threshold (typically around 10-20 mM ammonium sulfate), yeast cells perceive this as a signal of impending starvation. In response, they activate a cascade of genetic and metabolic changes that redirect resources towards spore formation. This nutrient-sensing mechanism is mediated by the TOR (Target of Rapamycin) signaling pathway, which acts as a molecular switch, shifting the cell's focus from growth and proliferation to survival and sporulation.

PH Changes: A Subtle yet Powerful Trigger

While less understood than nutrient depletion, pH alterations also significantly influence sporulation initiation. A shift towards a more acidic environment (pH 3.5-4.0) has been shown to promote sporulation in certain yeast species, such as *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*. This pH-dependent response is thought to be linked to changes in membrane potential and intracellular signaling, ultimately leading to the activation of sporulation-specific genes. Interestingly, the optimal pH range for sporulation varies among yeast species, highlighting the importance of species-specific adaptations to environmental cues.

Environmental Stressors: A Multifaceted Challenge

Beyond nutrient depletion and pH changes, various environmental stressors can induce sporulation in yeast. These include:

- Temperature stress: Exposure to elevated temperatures (37-42°C) can trigger sporulation in some yeast species, possibly as a means of surviving heat shock.

- Oxidative stress: Reactive oxygen species (ROS), generated by exposure to hydrogen peroxide or other oxidizing agents, can induce sporulation as a protective mechanism against cellular damage.

- Osmotic stress: High salt concentrations or other osmotic stressors can lead to sporulation, enabling yeast to withstand desiccation and other harsh conditions.

The interplay between these stressors and the underlying molecular mechanisms remains an active area of research, with potential applications in biotechnology and food production. For instance, controlled sporulation induction could enhance the shelf life and stress tolerance of yeast-based products, such as bread, beer, and biofuels.

Practical Considerations for Sporulation Induction

To induce sporulation in yeast cultures, researchers and biotechnologists can manipulate the aforementioned conditions. A typical sporulation medium might contain:

- Low nitrogen content: 0.1-0.5% ammonium sulfate or other nitrogen sources

- Acidic pH: Adjusted to 3.5-4.0 using acetic acid or other buffers

- Stress-inducing agents: 0.5-1.0 mM hydrogen peroxide, 1.0-2.0 M sorbitol, or other stressors, depending on the desired outcome

By carefully controlling these parameters, it is possible to optimize sporulation efficiency and yield, ultimately harnessing the unique properties of yeast spores for various applications. As our understanding of sporulation initiation conditions continues to evolve, so too will our ability to manipulate this process for the benefit of science and industry.

Does Stun Spore Work on Bug Types? Exploring Pokémon Battle Mechanics

You may want to see also

Meiosis process: Yeast undergoes meiosis, reducing chromosome number, essential for spore formation

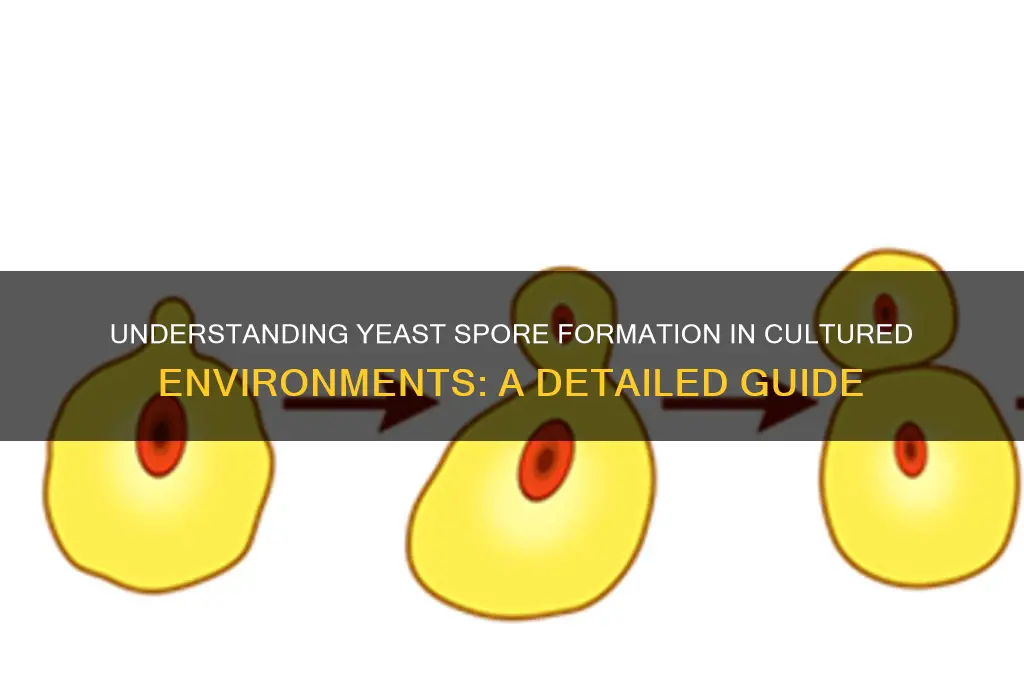

Yeast, a single-celled eukaryote, employs meiosis as a strategic mechanism to ensure genetic diversity and survival under adverse conditions. Unlike mitosis, which maintains the chromosome number, meiosis reduces the chromosome count by half, producing haploid cells. This reduction is pivotal for spore formation, as it allows yeast to generate genetically unique spores capable of withstanding harsh environments. In *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, for instance, diploid cells (2n) undergo meiosis to form four haploid spores (n), each encased in an ascus. This process is not merely a cellular event but a survival tactic, enabling yeast to persist in nutrient-depleted or stressful conditions.

The meiosis process in yeast is tightly regulated and consists of two divisions: Meiosis I and Meiosis II. During Meiosis I, homologous chromosomes pair, exchange genetic material via crossing over, and then segregate, reducing the chromosome number from 2n to n. Meiosis II resembles mitosis, dividing the haploid cells further without chromosome replication. This results in four genetically distinct haploid nuclei, each destined to become a spore. Notably, the efficiency of this process is influenced by environmental cues, such as nutrient availability and temperature. For example, nitrogen starvation triggers the initiation of meiosis in yeast, highlighting the interplay between external conditions and cellular responses.

From a practical standpoint, understanding meiosis in yeast is crucial for industries like brewing and biotechnology. In brewing, sporulation can affect beer quality, as spores may survive pasteurization. To mitigate this, brewers often control fermentation conditions to discourage sporulation. In biotechnology, yeast meiosis is exploited for genetic studies, as it facilitates the mapping of genes and the creation of recombinant strains. For instance, researchers use sporulation to analyze genetic crosses, providing insights into inheritance patterns. This underscores the dual role of meiosis in yeast: a survival mechanism in nature and a tool in applied science.

A comparative analysis reveals that yeast meiosis shares fundamental principles with other eukaryotes but exhibits unique adaptations. Unlike multicellular organisms, yeast undergoes sporulation within a protective ascus, enhancing spore durability. Additionally, yeast’s rapid life cycle allows for quick observation of meiotic stages, making it an ideal model organism. However, yeast lacks the complex cellular differentiation seen in higher eukaryotes, simplifying the study of meiosis. This simplicity, coupled with genetic tractability, positions yeast as a cornerstone in meiosis research, offering a window into the conserved mechanisms of sexual reproduction across species.

In conclusion, the meiosis process in yeast is a finely tuned cellular program that underpins spore formation, blending survival strategy with scientific utility. By reducing the chromosome number and fostering genetic diversity, meiosis ensures yeast’s resilience in challenging environments. Whether in industrial applications or genetic research, this process exemplifies the elegance of nature’s solutions to biological challenges. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, mastering the intricacies of yeast meiosis opens doors to innovation and discovery, bridging the gap between fundamental biology and practical applications.

Can Toxic Mold Spore Penetrate Drywall? Facts and Risks Revealed

You may want to see also

Ascus development: Spores develop within an ascus, a protective sac formed during sporulation

Spores in yeast cultures are not formed through the ascus structure, as this is a characteristic of ascomycete fungi, a group that includes many molds and some yeasts but not the commonly studied Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s or brewer’s yeast). However, understanding ascus development provides insight into spore formation in ascomycetes, which share evolutionary ties with yeast. The ascus, a microscopic sac, is a hallmark of this process, encapsulating spores in a protective environment until conditions favor their release.

Formation of the ascus begins with a diploid cell undergoing meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing four haploid nuclei. These nuclei then migrate into the developing ascus, where they undergo mitosis to form eight haploid nuclei. Each nucleus is enveloped by cytoplasm and a cell wall, resulting in the formation of eight ascospores within the ascus. This protective sac acts as a barrier against environmental stressors, ensuring the survival of spores until germination is feasible.

The development of the ascus is tightly regulated by environmental cues, particularly nutrient deprivation and temperature shifts. For instance, in *Neurospora crassa*, a model ascomycete, sporulation is induced by transferring cultures to a nutrient-poor medium at 25°C. The ascus wall is composed of chitin and glucan, providing structural integrity while remaining permeable to small molecules. This balance ensures spores remain viable yet shielded from harsh conditions.

Practical considerations for observing ascus development include using a hemocytometer and 40x magnification to monitor ascus formation over 48–72 hours. Staining with calcofluor white highlights the chitinous ascus wall under UV light, aiding visualization. For educators or hobbyists, *Sordaria fimicola* is an accessible species for demonstrating ascus development, as its black ascospores are easily visible under a dissecting microscope.

In contrast to yeast’s budding or fission-based reproduction, ascus development exemplifies a distinct survival strategy in fungi. While yeast spores (ascospores in some species) lack the ascus structure, understanding this process underscores the diversity of fungal reproductive mechanisms. By studying ascus development, researchers gain insights into fungal resilience and adaptability, with applications in biotechnology, agriculture, and medicine.

Invisible Spores: Are Our Hands Carrying Hidden Microbial Hitchhikers?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore wall formation: Layers of mannoproteins and chitin create a durable spore wall

Yeast spores, known as ascospores, are encased in a robust spore wall that ensures their survival in harsh conditions. This wall is not a singular structure but a complex, layered composition primarily of mannoproteins and chitin. Mannoproteins, a combination of proteins and mannose-rich oligosaccharides, form the outer layer, providing flexibility and adhesion. Beneath this lies chitin, a tough polysaccharide that confers rigidity and structural integrity. Together, these layers create a durable barrier that protects the spore’s genetic material from environmental stressors like heat, desiccation, and chemicals.

To understand the formation of this wall, consider the process as a precise, step-by-step assembly. During sporulation, yeast cells undergo meiosis, and the resulting spores begin synthesizing mannoproteins and chitin in a coordinated manner. Mannoproteins are first secreted and anchored to the spore’s surface, forming a mesh-like outer layer. Chitin is then deposited beneath, creating a sturdy scaffold. This layered approach ensures the spore wall is both resilient and adaptable, capable of withstanding extreme conditions while maintaining the spore’s viability for years.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore wall formation is crucial for industries like food preservation and biotechnology. For instance, in winemaking, yeast spores with robust walls can survive the fermentation process, influencing the final product’s flavor and quality. To enhance spore durability, researchers have experimented with manipulating mannoprotein and chitin synthesis. For example, increasing mannose availability during sporulation can thicken the outer layer, improving adhesion to surfaces. Conversely, reducing chitin synthesis weakens the wall, making spores more susceptible to degradation—a technique useful in controlled spore release applications.

A comparative analysis reveals that yeast spore walls share similarities with fungal spores, both relying on chitin for strength. However, yeast’s incorporation of mannoproteins is unique, offering advantages like enhanced surface interactions and resistance to enzymatic breakdown. This distinction highlights the evolutionary adaptation of yeast to thrive in diverse environments. By studying these differences, scientists can develop targeted strategies to either preserve or disrupt spore walls, depending on the application.

In conclusion, the spore wall’s layered structure of mannoproteins and chitin is a marvel of biological engineering. Its formation is a tightly regulated process that ensures spore survival and functionality. Whether in industrial settings or natural ecosystems, this durable wall plays a pivotal role in yeast’s lifecycle. By leveraging this knowledge, researchers and practitioners can optimize yeast cultures for specific purposes, from food production to biotechnology, ensuring efficiency and reliability in every application.

Aspirating Fungal Spores from Adherent Cells: Techniques and Considerations

You may want to see also

Maturation and release: Spores mature, dehydrate, and are released when the ascus ruptures

Spores in yeast cultures, particularly in ascomycetes like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, undergo a critical maturation phase within the ascus—a sac-like structure that houses the developing spores. During this stage, the spores accumulate storage compounds such as carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins, which are essential for survival during dormancy. Simultaneously, the spore cell wall thickens, providing structural integrity and protection against environmental stressors like heat, desiccation, and chemicals. This maturation process is tightly regulated by genetic and environmental cues, ensuring the spores are fully prepared for long-term survival outside the ascus.

Dehydration is a key step in spore maturation, reducing water content to levels that inhibit metabolic activity and preserve cellular integrity. This desiccation process is facilitated by the accumulation of compatible solutes, such as glycerol, which act as osmoprotectants and stabilize macromolecules. As the spores dehydrate, they become increasingly resistant to harsh conditions, a trait that is vital for their dispersal and persistence in diverse environments. This phase is not merely a passive drying process but an active, genetically controlled transformation that primes the spores for release.

The release of mature spores occurs when the ascus ruptures, a process triggered by environmental signals such as nutrient depletion or changes in pH. In laboratory cultures, this can be induced by manipulating growth conditions, such as transferring yeast cells to a sporulation medium (e.g., 1% potassium acetate, 0.1% yeast extract, and 0.05% dextrose) and incubating at 25–30°C for 5–7 days. The ascus wall weakens as the spores mature, eventually breaking open to release the spores into the environment. This release mechanism ensures efficient dispersal, allowing spores to colonize new habitats or survive until conditions improve.

Practical considerations for optimizing spore release include monitoring culture conditions closely, as deviations in temperature, pH, or nutrient availability can delay or inhibit ascus rupture. For researchers or biotechnologists, harvesting spores at the right time is crucial; over-incubation can lead to spore germination, while premature harvesting results in immature, non-viable spores. A simple yet effective tip is to observe the culture under a microscope: when most asci appear translucent and spores are clearly visible, the culture is ready for spore collection. This ensures maximum yield and viability for downstream applications, such as fermentation, genetic studies, or preservation.

In comparison to other microbial spore-forming processes, yeast sporulation is uniquely dependent on the ascus structure, which not only nurtures spore development but also controls their release. This contrasts with bacteria like *Bacillus*, where spores are released through lysis of the mother cell. Understanding the maturation and release of yeast spores highlights the elegance of their life cycle, offering insights into survival strategies that have evolved over millennia. By mastering these processes, scientists can harness yeast spores for biotechnology, food production, and even space exploration, where their resilience makes them ideal candidates for long-duration missions.

Exploring Spore's Multiplayer Mode: Cooperative Gameplay and Online Features

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process of spore creation in yeast cultures is called sporulation, a form of sexual reproduction in which haploid cells (spores) are produced within a resistant ascus.

Sporulation in yeast, such as *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, is typically triggered by nutrient deprivation, particularly the lack of nitrogen and a non-fermentable carbon source, which forces the yeast to enter a survival mode.

Under optimal conditions, yeast sporulation usually takes about 5–7 days, during which the cells undergo meiosis, spore wall formation, and maturation into heat-resistant spores.

No, not all yeast species can produce spores. Only certain species, like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, undergo sporulation, while others reproduce primarily through asexual budding.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![One in a Mill Instant Dry Yeast | 1.1 LB (Pack Of 1) [IMPROVED] Fast Acting Self Rising Yeast for Baking Bread, Cake, Pizza Dough Crust | Kosher | Quick Rapid Rise Leavening Agent for Pastries](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71frk5lZTFL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![One in a Mill Instant Dry Yeast | 1.1 LB (Pack Of 2) [IMPROVED] Fast Acting Self Rising Yeast for Baking Bread, Cake, Pizza Dough Crust | Kosher | Quick Rapid Rise Leavening Agent for Pastries](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71sPdf4U+2L._AC_UL320_.jpg)