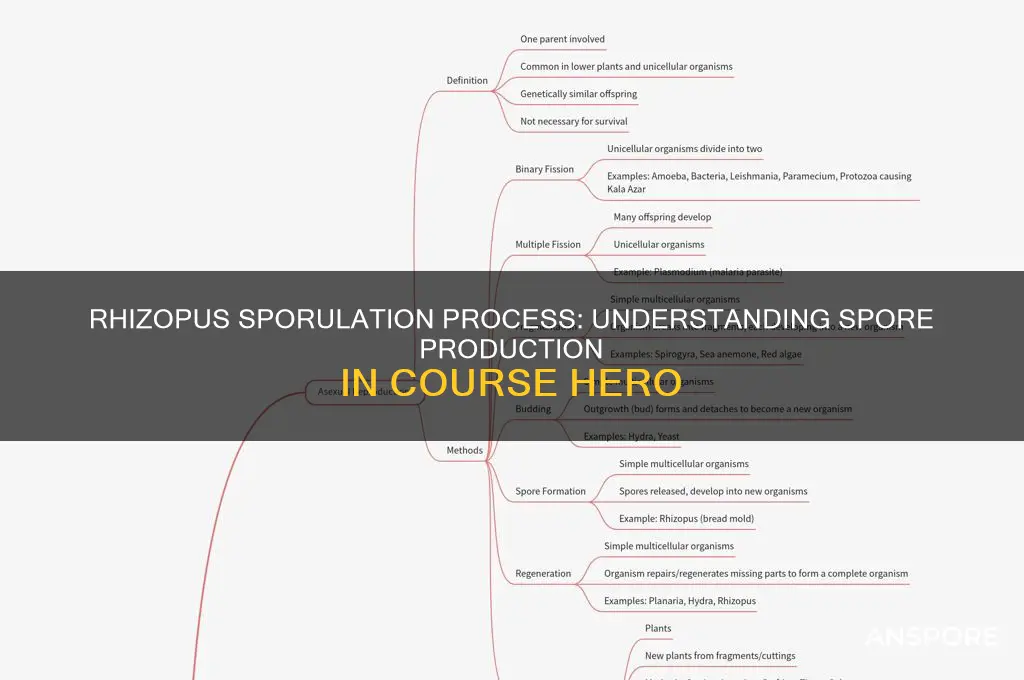

Rhizopus, a common genus of fungi belonging to the Zygomycota phylum, produces spores through a unique and fascinating process. In this organism, spores are primarily generated via asexual reproduction, specifically through the formation of sporangiospores. The process begins with the development of a sporangium, a spherical structure at the tip of a specialized hyphal branch called a sporangiophore. Within the sporangium, hundreds to thousands of haploid spores are produced through mitosis. As the sporangium matures, it eventually ruptures, releasing the spores into the environment. These spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by air currents, allowing Rhizopus to colonize new substrates efficiently. Understanding the mechanisms of spore production in Rhizopus not only sheds light on its life cycle but also highlights its ecological significance as a decomposer and occasional pathogen.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sporangiospore Formation | Spores are produced inside a spherical structure called a sporangium. |

| Sporangiophore Development | A specialized hyphal stalk (sporangiophore) grows upward, bearing the sporangium. |

| Sporangium Maturation | The sporangium matures, filling with haploid spores (sporangiospores). |

| Sporangium Color | The sporangium is typically black or dark due to melanin pigmentation. |

| Spore Release Mechanism | The sporangium wall ruptures, releasing spores into the environment. |

| Spore Dispersal | Spores are dispersed by air currents, water, or physical contact. |

| Spore Germination | Spores germinate under favorable conditions, forming new hyphae. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Sporulation occurs during the asexual phase of the Rhizopus life cycle. |

| Environmental Triggers | Sporulation is often triggered by nutrient depletion or environmental stress. |

| Genetic Basis | Controlled by specific genes regulating sporangium and spore development. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporangiospore formation process in Rhizopus

Sporangiospore formation in *Rhizopus* is a fascinating process that begins with the maturation of the sporangium, a spherical structure at the tip of the sporangiophore. This process is triggered by environmental cues such as nutrient depletion or changes in humidity, signaling the fungus to transition from vegetative growth to reproductive mode. Inside the sporangium, haploid nuclei undergo mitosis, producing numerous nuclei that migrate to the periphery of the structure. Concurrently, cytoplasm accumulates and differentiates into protoplasmic masses, each enveloping a nucleus. These protoplasmic masses then develop cell walls, transforming into sporangiospores—the primary means of asexual reproduction in *Rhizopus*.

The formation of sporangiospores is a highly coordinated event, showcasing the fungus’s adaptability to its environment. Once mature, the sporangium wall ruptures, releasing the spores into the air. This dispersal mechanism is crucial for the fungus’s survival, allowing it to colonize new substrates and escape adverse conditions. Interestingly, the sporangiospores are multicellular and remain connected by cytoplasmic bridges, a feature that distinguishes them from the unicellular spores of other fungi. This multicellular nature enhances their resilience, enabling them to withstand desiccation and other environmental stresses.

To observe this process in a laboratory setting, one can cultivate *Rhizopus* on a nutrient-rich medium such as potato dextrose agar. After 2–3 days of incubation at 25–30°C, sporangiophores will emerge, topped with sporangia. Microscopic examination at 400x magnification reveals the sporangiospores within the sporangium, appearing as densely packed, round structures. For educational purposes, staining with cotton blue or lactophenol blue enhances visibility, allowing students to clearly distinguish the spores from the surrounding tissue.

A comparative analysis highlights the efficiency of sporangiospore formation in *Rhizopus* relative to other fungal reproductive strategies. Unlike the single-celled conidia of *Aspergillus* or the complex zygospores of *Mucor*, sporangiospores combine rapid production with multicellular robustness. This dual advantage ensures both quick dispersal and higher survival rates, making *Rhizopus* a dominant decomposer in nutrient-rich environments like soil and decaying organic matter. Understanding this process not only sheds light on fungal biology but also has practical applications in fields such as food spoilage prevention and biotechnology.

In conclusion, the sporangiospore formation process in *Rhizopus* is a remarkable example of fungal adaptation and efficiency. From the environmental triggers initiating sporangium maturation to the multicellular resilience of the spores, each step is finely tuned for survival and propagation. By studying this process, researchers and students alike gain insights into the intricate mechanisms driving fungal life cycles, with potential applications ranging from education to industry. Whether in a classroom or a lab, observing sporangiospore formation offers a tangible connection to the microscopic world of *Rhizopus*.

Unlocking Rogue and Epic Modes in Spore: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Role of sporangium in spore production

Sporangia in *Rhizopus* serve as the factories for spore production, playing a critical role in the organism's life cycle. These spherical structures, borne at the tips of specialized stalks called sporangiophores, house the developing spores. Within the sporangium, haploid nuclei undergo mitosis, generating numerous nuclei that migrate to the periphery. Here, each nucleus becomes enveloped by a cell wall, forming a mature spore. This process, known as sporogenesis, ensures the production of a large number of spores, each capable of initiating a new fungal colony under favorable conditions.

The sporangium’s structure is optimized for spore dispersal, a key survival strategy for *Rhizopus*. Its thin, delicate walls dry and rupture easily, releasing the spores into the environment. This mechanism, coupled with the sporangium’s elevated position on the sporangiophore, maximizes the potential for wind or physical disturbance to carry spores away. For example, in a laboratory setting, gently tapping a slide containing *Rhizopus* will demonstrate this dispersal, as spores are released in a cloud-like manner. This efficient dispersal system highlights the sporangium’s dual role: not only as a site of spore production but also as a launchpad for their distribution.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the sporangium’s role is essential for controlling *Rhizopus* growth, particularly in contexts like food spoilage or laboratory cultivation. For instance, in bread mold experiments, students can observe sporangia under a microscope at 40x magnification, noting their spherical shape and the dark spores within. To inhibit spore production, maintaining low humidity (below 60%) and temperatures under 25°C can suppress sporangium development. Conversely, for cultivating *Rhizopus*, providing a warm (25–30°C), humid environment on a starch-rich medium will promote robust sporangium formation and spore release.

Comparatively, the sporangium in *Rhizopus* differs from structures like conidia in *Aspergillus* or basidiospores in mushrooms, which are produced directly on hyphae or specialized cells. The sporangium’s encapsulation of spores offers protection during development and aids in coordinated dispersal, a feature particularly advantageous for saprophytic fungi like *Rhizopus* that rely on rapid colonization of nutrient sources. This distinction underscores the sporangium’s unique evolutionary adaptation, balancing spore production and dispersal efficiency.

In conclusion, the sporangium is indispensable in *Rhizopus* spore production, functioning as both a developmental chamber and a dispersal unit. Its structure and location are finely tuned to ensure the survival and propagation of the species. Whether in educational settings, industrial applications, or natural environments, recognizing the sporangium’s role provides actionable insights for studying, controlling, or harnessing *Rhizopus* growth. By focusing on this specific structure, one gains a deeper appreciation for the intricate mechanisms driving fungal reproduction.

Can Bacteria from Spores Survive and Thrive in Extreme Conditions?

You may want to see also

Environmental factors influencing spore development

Spores in *Rhizopus*, a common zygomycete fungus, are not merely products of genetic programming but are significantly shaped by their environment. Temperature, for instance, acts as a critical regulator. Optimal spore development in *Rhizopus* typically occurs between 25°C and 30°C. Below 20°C, sporulation slows dramatically, while temperatures exceeding 35°C can inhibit the process entirely. This thermal sensitivity underscores the fungus’s adaptation to temperate and tropical climates, where it thrives in decaying organic matter.

Humidity and moisture levels are equally pivotal. *Rhizopus* requires a water activity (aw) of at least 0.90 for spore germination and subsequent sporulation. In environments with aw below 0.85, sporulation is severely impaired. This dependency on moisture explains why *Rhizopus* is frequently found in damp substrates like bread, fruits, and soil. However, excessive waterlogging can lead to anaerobic conditions, stifling spore development. Thus, a balance between moisture availability and aeration is essential.

Light exposure, though often overlooked, plays a subtle yet significant role. While *Rhizopus* does not require light for growth, studies indicate that blue light (450–490 nm) can enhance sporulation rates by up to 20%. This photostimulation is thought to activate specific metabolic pathways involved in spore formation. Conversely, prolonged exposure to UV light can be detrimental, damaging DNA and reducing spore viability. Practical applications of this knowledge include controlled light conditions in laboratory cultures to optimize spore yield.

Nutrient availability is another environmental factor that cannot be ignored. *Rhizopus* thrives in carbohydrate-rich environments, with glucose and sucrose concentrations of 1–2% (w/v) promoting robust sporulation. Nitrogen sources, such as ammonium nitrate or peptone, are also crucial, but excessive nitrogen (above 0.5% w/v) can divert metabolic resources toward vegetative growth at the expense of sporulation. This nutrient-dependent shift highlights the fungus’s ability to prioritize survival strategies based on resource availability.

Finally, pH levels influence spore development by affecting enzyme activity and nutrient uptake. *Rhizopus* prefers a slightly acidic to neutral pH range of 5.5–7.0. At pH levels below 5.0 or above 8.0, sporulation declines sharply. For instance, in bread spoilage, the natural pH shift from 5.0 to 6.0 during fermentation creates an ideal environment for *Rhizopus* sporulation. Adjusting pH in experimental setups or industrial processes can thus be a strategic tool to control spore production.

In summary, spore development in *Rhizopus* is a finely tuned response to environmental cues. By manipulating temperature, humidity, light, nutrients, and pH, researchers and practitioners can optimize sporulation for various applications, from biotechnology to food preservation. Understanding these factors not only deepens our knowledge of fungal biology but also empowers practical interventions in managing *Rhizopus* growth.

Exploring Spore Drives: Fact or Fiction in Modern Science?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Life cycle stages of Rhizopus spores

Rhizopus, a common mold found on decaying organic matter, produces spores through a complex yet efficient life cycle. Understanding this cycle is crucial for fields like mycology, agriculture, and food preservation. The process begins with sporulation, where the fungus develops sporangiospores within a spherical structure called a sporangium. These spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by air, ensuring the fungus’s survival and propagation.

The life cycle of Rhizopus spores unfolds in distinct stages. Stage 1: Germination occurs when a mature spore lands on a suitable substrate, such as bread or fruit. Under optimal conditions (25–30°C and high humidity), the spore absorbs water, swells, and germinates within 2–4 hours. Stage 2: Hyphal Growth follows, where the germinated spore develops into a network of thread-like structures called hyphae. These hyphae penetrate the substrate, secreting enzymes to break down nutrients for absorption.

Stage 3: Sporangiophore Formation marks the transition to reproduction. As the fungus matures, specialized hyphae called sporangiophores grow vertically, bearing sporangia at their tips. Each sporangium contains thousands of spores, which mature within 12–24 hours. Stage 4: Sporulation and Dispersal is the final stage, where the sporangium wall ruptures, releasing spores into the environment. This stage is critical for the fungus’s survival, as spores can remain dormant for months until conditions favor germination.

Practical tips for managing Rhizopus growth include maintaining low humidity (below 60%) and storing food in cool, dry environments. For laboratory studies, agar plates with glucose or starch can be used to observe the life cycle under controlled conditions. Understanding these stages not only aids in preventing food spoilage but also highlights the adaptability of Rhizopus in diverse ecosystems.

Tyndallization: Effective Method to Eliminate Bacteria and Spores?

You may want to see also

Sporangiolites and their function in reproduction

Sporangiolites, though often overshadowed by their larger counterparts, sporangia, play a crucial role in the reproductive strategy of *Rhizopus*. These microscopic structures are essentially miniature sporangia, each housing a limited number of spores. Their formation is a testament to the fungus's adaptability, allowing for efficient spore dispersal even in resource-limited conditions.

Unlike the more prominent sporangia that develop at the tips of specialized stalks, sporangiolites emerge directly on the hyphae, the filamentous structures that make up the fungus's body. This direct integration into the hyphal network facilitates rapid spore production and release, ensuring the fungus can capitalize on fleeting opportunities for colonization.

Imagine a sprawling network of threads, each capable of sprouting tiny spore-filled sacs. This is the reality within a *Rhizopus* colony, where sporangiolites act as decentralized spore factories. Their small size and direct attachment to the hyphae allow for a continuous and localized production of spores, increasing the chances of successful dispersal even in confined environments.

This decentralized approach to spore production offers several advantages. Firstly, it maximizes spore output by utilizing the entire hyphal network, not just specialized structures. Secondly, the smaller size of sporangiolites allows for more efficient dispersal, as they can be easily carried by air currents or adhere to passing organisms.

While sporangiolites contribute significantly to *Rhizopus*'s reproductive success, their formation is influenced by environmental cues. Factors like nutrient availability, humidity, and temperature play a crucial role in triggering their development. Understanding these triggers can be valuable for controlling *Rhizopus* growth in agricultural settings, where it can be both a beneficial decomposer and a destructive pathogen.

In essence, sporangiolites represent a sophisticated adaptation in *Rhizopus*, enabling efficient and widespread spore dispersal. Their decentralized production and responsiveness to environmental cues highlight the fungus's remarkable ability to thrive in diverse conditions. By studying these microscopic structures, we gain valuable insights into the intricate reproductive strategies of fungi and their impact on ecosystems.

Exploring Fungal Diversity: Do Tropical Islands Harbor More Spores?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Rhizopus, a type of zygomycete fungus, produces spores through a process called sporangiospore formation. This involves the development of a sporangium, a spherical structure at the end of a stalk, which contains numerous spores.

Spore formation in Rhizopus takes place at the tips of specialized hyphae called sporangiophores. These structures grow upwards, bearing a sporangium at their apex, where the spores are generated and eventually released.

When the spores inside the sporangium mature, the sporangium wall breaks down, allowing the spores to be dispersed. This release can be facilitated by wind, water, or even insects, aiding in the fungus's propagation.

Spores in Rhizopus serve as a means of asexual reproduction and dispersal. They are lightweight and easily carried by air currents, enabling the fungus to colonize new habitats and survive unfavorable environmental conditions.