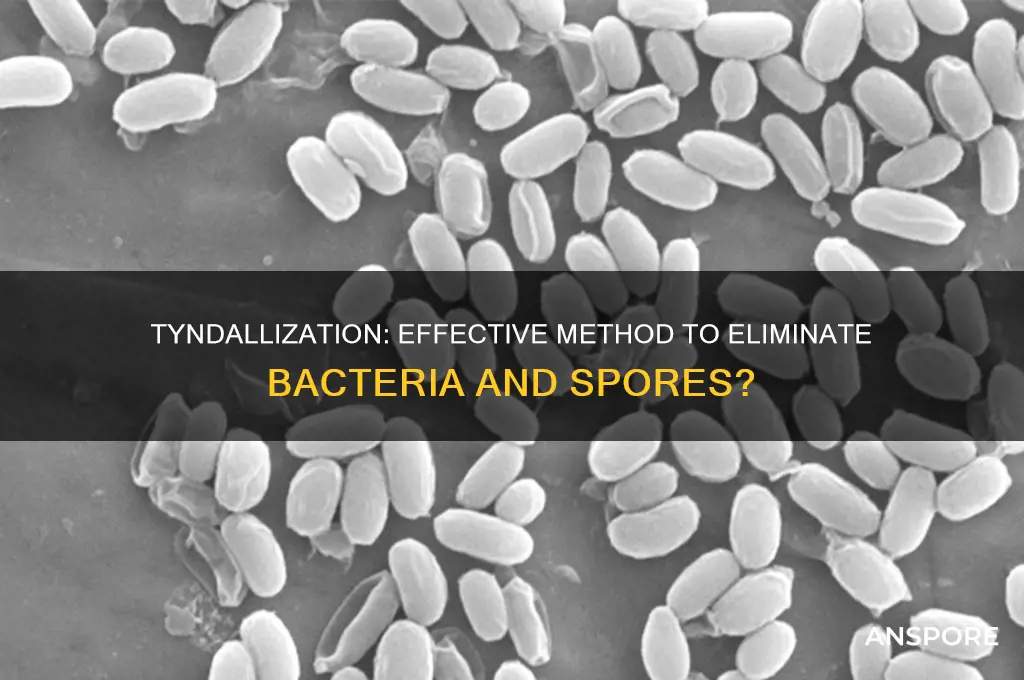

Tyndallization is a thermal sterilization method designed to eliminate both vegetative bacteria and bacterial spores from substances, particularly those that are heat-sensitive and cannot withstand the high temperatures of autoclaving. Unlike traditional autoclaving, which uses a single prolonged exposure to high heat, Tyndallization involves a series of shorter heating cycles at 100°C (boiling point) interspersed with incubation periods at room temperature. This process aims to activate any dormant spores that may survive the initial heating, allowing them to germinate into vegetative forms, which are then more susceptible to destruction in subsequent heating cycles. While effective for many applications, Tyndallization is less reliable than autoclaving and requires careful execution to ensure complete sterilization, as some highly resistant spores may still survive. Its primary advantage lies in its gentleness, making it suitable for heat-sensitive materials where autoclaving would cause degradation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Description | Tyndallization is a sterilization method involving multiple heating cycles at 100°C (boiling) followed by cooling periods. |

| Effect on Bacteria | Effectively removes vegetative (actively growing) bacteria. |

| Effect on Spores | Does not reliably remove bacterial spores. Spores survive the process and may germinate later. |

| Mechanism | Spores are heat-resistant and require higher temperatures (autoclaving at 121°C) or longer exposure for complete inactivation. |

| Applications | Suitable for heat-sensitive materials where autoclaving is not feasible. Often used in food preservation and laboratory settings. |

| Limitations | Not a reliable method for sterilizing materials containing bacterial spores. Requires additional steps or alternative methods for complete sterilization. |

| Comparison to Autoclaving | Less effective than autoclaving, which uses higher temperatures and pressure to kill both bacteria and spores. |

| Safety Considerations | Materials treated by tyndallization may still harbor spores, posing a risk of contamination if not handled properly. |

Explore related products

$26.99

What You'll Learn

- Tyndallization Process Overview: Heat treatment repeated over days to kill bacteria and spores in materials

- Effectiveness Against Spores: Targets spore-forming bacteria by disrupting germination and growth cycles effectively

- Comparison to Autoclaving: Less intense than autoclaving but suitable for heat-sensitive substances

- Applications in Food Preservation: Used in canning and preserving heat-sensitive foods safely

- Limitations and Risks: Inconsistent results if not performed correctly; requires precise temperature control

Tyndallization Process Overview: Heat treatment repeated over days to kill bacteria and spores in materials

The Tyndallization process is a method of sterilization that relies on a series of heat treatments to eliminate bacteria and spores from materials, particularly those that cannot withstand the high temperatures of autoclaving. Unlike traditional autoclaving, which uses a single, intense heat treatment, Tyndallization employs a more gradual approach, spreading the process over several days. This method is particularly useful for heat-sensitive substances like culture media, certain foods, and some laboratory materials that might degrade under continuous high heat.

The process begins with the material being heated to 100°C (212°F) for 30 minutes, a temperature sufficient to kill vegetative bacteria but not spores. After cooling, the material is incubated at room temperature for 24 hours, allowing any surviving spores to germinate into vegetative cells. This cycle is repeated two more times, ensuring that any spores that germinate during the incubation periods are subsequently destroyed in the next heating step. The total process spans three days, with each heating and incubation cycle playing a critical role in achieving sterilization.

One of the key advantages of Tyndallization is its ability to sterilize materials without the need for specialized equipment like autoclaves, making it accessible in settings with limited resources. However, it is not suitable for all materials, as repeated heating can alter the properties of certain substances. For example, heat-labile nutrients in culture media may degrade, and some foods may lose texture or flavor. Therefore, careful consideration of the material’s compatibility with the process is essential.

Despite its effectiveness, Tyndallization is not as rapid or foolproof as autoclaving. The longer duration and multiple steps increase the risk of contamination if aseptic techniques are not strictly followed. Additionally, it is less effective against highly resistant spores, such as those of *Clostridium botulinum*. Practitioners must weigh these limitations against the benefits when choosing this method for sterilization.

In practical applications, Tyndallization is often used in microbiology laboratories for preparing culture media and in food preservation, particularly for canned goods. For instance, home canners might use a similar process to sterilize low-acid foods, though commercial operations typically prefer more efficient methods. When implementing Tyndallization, it’s crucial to monitor temperature and time meticulously, as deviations can compromise the outcome. This method, though labor-intensive, remains a valuable tool in situations where autoclaving is impractical or unavailable.

Windblown Spores: A Land-Based Reproductive Adaptation Strategy Explored

You may want to see also

Effectiveness Against Spores: Targets spore-forming bacteria by disrupting germination and growth cycles effectively

Spores, the resilient survival forms of certain bacteria, pose a unique challenge in sterilization processes. Tyndallization, a thermal sterilization method, tackles this challenge head-on by exploiting the very mechanism that makes spores so hardy: their germination cycle. Unlike methods that rely on continuous high heat, Tyndallization uses intermittent heating, allowing spores to partially activate before destroying them during subsequent heat treatments.

This multi-stage approach effectively disrupts the germination and growth cycles of spore-forming bacteria. The initial heating step at 100°C (212°F) for 30 minutes kills vegetative cells and triggers spore germination. Subsequent incubations at room temperature encourage further spore activation, making them vulnerable to the final heating stages. This repeated cycle of heating and incubation ensures that even the most resistant spores are eliminated.

Imagine a battlefield where the enemy hides in impenetrable bunkers. Tyndallization acts like a cunning strategist, luring the enemy out of their shelters with a false sense of security before launching a decisive attack. By mimicking the conditions necessary for spore germination, Tyndallization exposes these resilient forms to their ultimate demise.

This method is particularly effective against spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum*, a common culprit in foodborne illnesses. While autoclaving, a more aggressive sterilization method, can achieve similar results, Tyndallization offers a gentler alternative suitable for heat-sensitive materials like certain foods and beverages.

It's important to note that Tyndallization requires meticulous execution. Precise temperature control and adherence to the specific heating and incubation times are crucial for success. Deviations can lead to incomplete sterilization, leaving behind viable spores. Therefore, while Tyndallization is a powerful tool against spore-forming bacteria, it demands careful application to ensure its effectiveness.

Are Spores a Fungus? Unraveling the Microscopic Mystery

You may want to see also

Comparison to Autoclaving: Less intense than autoclaving but suitable for heat-sensitive substances

Tyndallization and autoclaving are both sterilization methods, but they differ significantly in intensity and application. Autoclaving uses high-pressure steam at 121°C (250°F) for 15–20 minutes to kill bacteria, spores, and other microorganisms. This method is highly effective but can degrade heat-sensitive materials like certain proteins, plastics, or culture media. Tyndallization, on the other hand, employs a series of heating steps at 100°C (212°F) over several days, interspersed with incubation periods. This gentler approach is less likely to damage heat-sensitive substances, making it a preferred choice for specific applications.

Consider a laboratory scenario where you need to sterilize a nutrient broth containing heat-labile enzymes. Autoclaving could denature these enzymes, rendering the broth ineffective. Tyndallization, however, allows the broth to retain its enzymatic activity while still achieving sterilization. The process involves heating the broth to 100°C for 30 minutes, cooling it, and repeating this cycle three times over 24–48 hours. This method exploits the fact that spores germinate into vegetative cells during the incubation periods, which are then killed in the subsequent heating steps.

While tyndallization is less intense, it requires careful execution to ensure effectiveness. For instance, improper sealing of containers or insufficient heating can lead to contamination. Additionally, the longer processing time (up to 48 hours) may not be feasible for time-sensitive workflows. However, for applications involving heat-sensitive substances like vaccines, antibiotics, or certain biological samples, tyndallization offers a viable alternative to autoclaving.

In practice, tyndallization is often used in microbiology labs for sterilizing culture media or in the pharmaceutical industry for heat-sensitive products. For example, a vaccine formulation containing temperature-sensitive antigens might undergo tyndallization to maintain its efficacy. To optimize results, ensure containers are properly sealed, use a water bath or steam source for uniform heating, and monitor temperature closely. While not as rapid as autoclaving, tyndallization’s ability to preserve heat-sensitive materials makes it an indispensable tool in specific contexts.

Growing Mushrooms Without Spores: Alternative Methods for Cultivation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Applications in Food Preservation: Used in canning and preserving heat-sensitive foods safely

Tyndallization is a thermal process that effectively reduces bacterial and spore contamination in heat-sensitive foods without damaging their quality. Unlike traditional sterilization methods that rely on continuous high heat, Tyndallization uses intermittent heating at 100°C (212°F) over several days. This process exploits the germination cycle of spores, which are more heat-resistant than their vegetative forms. By repeating the heating cycle, dormant spores that survive the first treatment are activated, only to be destroyed in subsequent rounds. This makes it ideal for preserving foods like dairy products, fermented vegetables, and certain fruits, where prolonged exposure to high temperatures would alter texture, flavor, or nutritional value.

For home canners and small-scale food producers, Tyndallization offers a practical alternative to pressure canning or chemical preservatives. The process begins with heating the food to 100°C for 30 minutes, followed by a cooling period of 24 hours. This cycle is repeated two to three times, ensuring that both bacteria and spores are eliminated. For example, when preserving heat-sensitive items like yogurt or sauerkraut, this method retains their probiotic cultures while ensuring safety. It’s crucial, however, to maintain strict hygiene during the cooling phases to prevent recontamination, as the food is not fully sterilized until the final cycle is complete.

One of the key advantages of Tyndallization is its ability to preserve the sensory and nutritional qualities of foods that would otherwise degrade under harsher preservation methods. For instance, delicate fruits like strawberries or raspberries can be safely canned without turning mushy or losing their vibrant color. Similarly, dairy-based products like cheese or milk retain their texture and flavor profiles. However, this method is not suitable for low-acid foods like meats or vegetables unless combined with other preservation techniques, such as adding vinegar or salt, to prevent the growth of pathogens during the cooling intervals.

Despite its benefits, Tyndallization requires careful execution to ensure effectiveness. The process is time-consuming, typically spanning three to four days, and demands precise temperature control. Home preservers should use a reliable thermometer and follow a strict schedule to avoid incomplete sterilization. Additionally, while Tyndallization reduces spore counts significantly, it does not guarantee absolute sterility, making proper storage conditions essential. Foods preserved this way should be stored in a cool, dark place and consumed within a reasonable timeframe to maintain safety and quality.

In summary, Tyndallization is a valuable tool for preserving heat-sensitive foods safely, offering a balance between microbial control and quality retention. Its application in canning and fermentation processes highlights its versatility, particularly for artisanal or specialty food producers. By understanding its mechanisms and limitations, users can harness this method to extend the shelf life of delicate products while preserving their unique characteristics. Whether for homemade jams, cultured dairy, or pickled vegetables, Tyndallization provides a scientifically grounded approach to food preservation that respects both tradition and innovation.

Are Spore Syringes Illegal? Understanding Legal Boundaries and Risks

You may want to see also

Limitations and Risks: Inconsistent results if not performed correctly; requires precise temperature control

Tyndallization, a process often hailed for its ability to eliminate bacteria and spores, is not without its pitfalls. One of its most critical limitations lies in the precision required to achieve consistent results. Unlike autoclaving, which relies on a single high-pressure steam cycle, Tyndallization involves multiple heating steps at 100°C (212°F) over several days. Each step must be executed flawlessly to ensure that vegetative bacteria are killed and spores, which survive the initial heat, are activated and subsequently destroyed in the following cycles. A single misstep—such as inadequate heating time or improper cooling—can render the process ineffective, leaving harmful spores intact.

Consider the practical implications of this precision requirement. For instance, if a laboratory technician fails to maintain the exact temperature of 100°C during any of the heating phases, spores may remain dormant and unscathed. Similarly, if the cooling period between cycles is rushed or incomplete, spores may not germinate, evading destruction in the next heating phase. This inconsistency is particularly problematic in industries like food preservation or pharmaceutical manufacturing, where even a small number of surviving spores can lead to contamination or product spoilage.

To mitigate these risks, strict adherence to protocol is essential. Each heating cycle should last 30 minutes at 100°C, followed by a cooling period of at least 24 hours to allow spores to germinate. This process is repeated three times, totaling 72 hours. Even minor deviations, such as a temperature fluctuation of just 2°C or a cooling period shortened by a few hours, can compromise the outcome. For this reason, Tyndallization is often reserved for situations where autoclaving is impractical, such as heat-sensitive materials, rather than being a first-line method.

The risks extend beyond mere inconsistency. In medical or pharmaceutical applications, incomplete sterilization can have severe consequences. For example, if Tyndallization is used to sterilize culture media for bacterial research, surviving spores could contaminate experiments, leading to inaccurate results. In food processing, residual spores could cause botulism or other foodborne illnesses if not eliminated. These risks underscore the need for rigorous training and monitoring when employing Tyndallization, as well as the importance of validating the process through spore testing.

Ultimately, while Tyndallization offers a viable alternative to autoclaving in specific scenarios, its success hinges on meticulous execution. Laboratories and industries must weigh the benefits of using this method against the potential for error and the critical nature of the application. For those who choose to employ Tyndallization, investing in calibrated equipment, standardized protocols, and ongoing staff training is non-negotiable. Only through such diligence can the risks of inconsistent results be minimized, ensuring the process fulfills its intended purpose.

Peracetic Acid's Power: Can It Effectively Inactivate Spores?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Tyndallization is a sterilization method that uses intermittent heating to kill bacteria and their spores. It involves heating the material to 100°C (boiling point) for 20-30 minutes, allowing it to cool, and repeating this process over several days. This cycle targets spores that may survive the first heating by activating them and then destroying them in subsequent heatings.

Yes, Tyndallization is effective at removing both vegetative bacteria and bacterial spores. However, it is less reliable than autoclaving and requires precise timing and temperature control. It is particularly useful for heat-sensitive materials that cannot withstand the high temperatures and pressures of autoclaving.

Yes, Tyndallization has limitations. It is time-consuming, requiring multiple heating cycles over several days. It may not be as effective as autoclaving for complete sterilization, especially if not performed correctly. Additionally, it is not suitable for all materials, as repeated heating can degrade heat-sensitive substances.