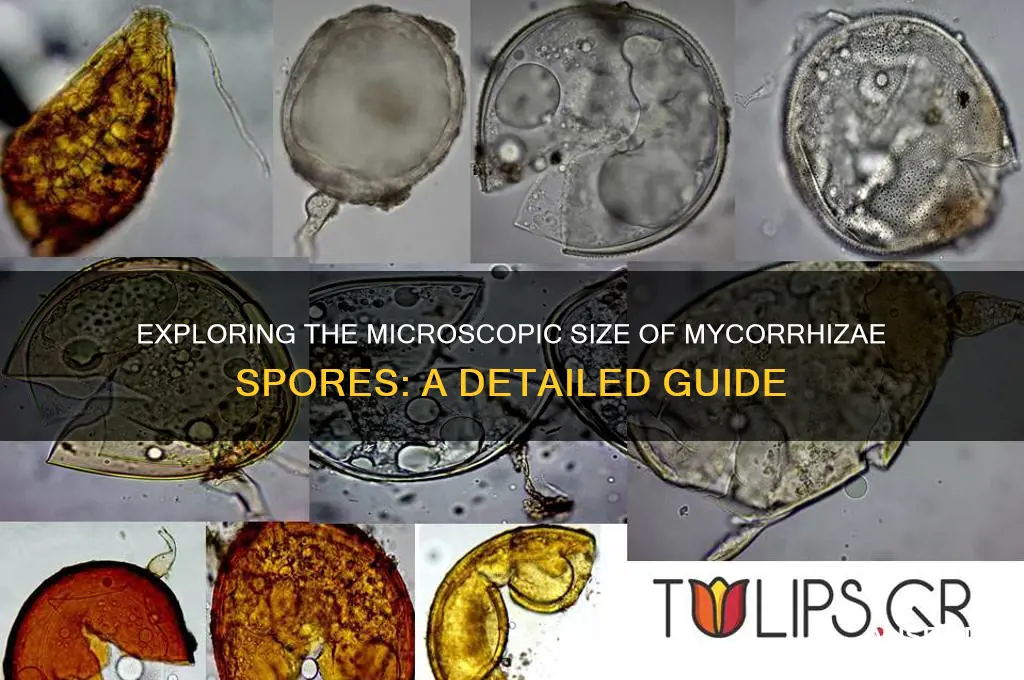

Mycorrhizae spores, the reproductive units of symbiotic fungi that form mutualistic relationships with plant roots, vary significantly in size depending on the species. Typically, these spores range from 10 to 100 micrometers (μm) in diameter, though some can be as small as 5 μm or as large as 200 μm. This size diversity reflects the wide array of mycorrhizal fungi, including arbuscular (AM), ectomycorrhizal (ECM), and ericoid types. Despite their microscopic scale, these spores play a crucial role in soil ecosystems, facilitating nutrient exchange between fungi and plants. Their size influences dispersal mechanisms, germination rates, and interactions with soil particles, making spore dimensions a key factor in understanding mycorrhizal ecology and function.

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

Spore size variability across mycorrhizal types

Mycorrhizal spores, the reproductive units of symbiotic fungi, exhibit significant size variability across different types, reflecting their ecological roles and evolutionary adaptations. For instance, arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi, which form extensive hyphal networks in plant roots, typically produce spores ranging from 10 to 500 micrometers in diameter. These larger spores are often multinucleate and thick-walled, enabling them to survive harsh soil conditions and disperse over long distances. In contrast, ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi, commonly associated with forest trees, produce smaller spores, usually between 5 and 50 micrometers. This size difference correlates with their dispersal strategies: ECM spores are often wind-dispersed and require lighter structures, while AM spores rely on soil organisms or water for movement.

Analyzing spore size variability reveals insights into mycorrhizal function. Larger AM spores act as energy reserves, storing lipids and carbohydrates that support fungal growth upon germination. This is particularly crucial in nutrient-poor soils, where rapid colonization of plant roots is essential. Conversely, the smaller size of ECM spores aligns with their role in forming dense, external hyphal sheaths around plant roots, which facilitate nutrient exchange in nutrient-rich environments. For researchers, measuring spore size using microscopy techniques (e.g., light or scanning electron microscopy) can help identify mycorrhizal types and assess soil health, as spore abundance and size distribution correlate with fungal diversity and ecosystem function.

Practical applications of understanding spore size variability extend to agriculture and restoration ecology. For example, when inoculating crops with AM fungi, selecting spore sizes appropriate for the soil type and crop root architecture can enhance colonization success. Larger spores may be more effective in coarse, sandy soils, where they are less likely to be washed away, while smaller spores might perform better in fine-textured soils with higher water retention. Similarly, in reforestation projects, matching ECM spore size to the dispersal mechanisms of the target ecosystem—such as wind patterns in open forests versus animal vectors in dense woodlands—can improve fungal establishment and tree survival rates.

A comparative study of spore size across mycorrhizal types highlights evolutionary trade-offs. Orchids, which form specialized mycorrhizae with fungi, often have minute spores (less than 1 micrometer), reflecting their dependence on fungal partners for germination and early seedling nutrition. This contrasts sharply with AM and ECM fungi, whose larger spores enable independent survival. Such comparisons underscore the importance of spore size as an adaptive trait, shaped by the specific demands of each mycorrhizal symbiosis. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, documenting spore size variability across ecosystems can contribute to global databases, aiding in the prediction of fungal responses to climate change and land-use shifts.

In conclusion, spore size variability across mycorrhizal types is a critical yet often overlooked aspect of fungal biology. By examining this variability through analytical, practical, and comparative lenses, we gain a deeper understanding of how fungi adapt to their environments and support plant health. Whether for scientific research, agricultural improvement, or ecological restoration, recognizing the significance of spore size can guide more effective strategies for harnessing the power of mycorrhizal symbioses.

Exploring the Microscopic Size of Bacterial Endospores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Measurement techniques for mycorrhizae spores

Mycorrhizae spores, critical for soil health and plant symbiosis, vary in size across species, typically ranging from 10 to 100 micrometers (μm) in diameter. Accurate measurement is essential for research, agriculture, and ecological studies, yet their small size and diverse morphology present unique challenges. Techniques for quantifying spore dimensions must balance precision with practicality, often leveraging advancements in microscopy and image analysis.

Microscopy Techniques: The Foundation of Spore Measurement

Light microscopy remains a cornerstone for mycorrhizae spore measurement, offering a cost-effective and accessible approach. Calibrated eyepiece micrometers or stage micrometers enable direct measurement of spore diameter under magnification. For greater precision, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) provides high-resolution images, revealing surface details and precise dimensions down to the nanometer scale. However, SEM is resource-intensive and requires sample preparation, limiting its use to specialized applications.

Image Analysis Software: Automating Precision

Advancements in digital image analysis have revolutionized spore measurement. Software tools like ImageJ or specialized mycology programs allow researchers to analyze microscope images, automatically calculating spore size, shape, and volume. These tools reduce human error and increase throughput, making them ideal for large datasets. For instance, thresholding algorithms can isolate spores from background debris, while machine learning models can classify species based on size distributions.

Flow Cytometry: High-Throughput Screening

Flow cytometry offers a rapid alternative for measuring spore size, particularly in agricultural settings. By suspending spores in a liquid medium, this technique measures light scattering and fluorescence, correlating these signals with spore dimensions. While less precise than microscopy for individual spores, flow cytometry excels in analyzing population-level size distributions, enabling quick assessments of spore viability and density in soil samples.

Practical Considerations and Limitations

Choosing the right measurement technique depends on the research question and available resources. For field studies, portable digital microscopes paired with smartphone apps provide a lightweight, cost-effective solution. In contrast, laboratory-based research may prioritize SEM or flow cytometry for detailed analysis. Regardless of method, standardization is critical—consistent sample preparation, calibration, and reporting protocols ensure comparability across studies.

Future Directions: Integrating Technology

Emerging technologies like microfluidics and artificial intelligence hold promise for spore measurement. Microfluidic devices can isolate and measure individual spores with minimal sample preparation, while AI-driven image analysis could automate species identification based on size and morphology. As these tools evolve, they will enhance our ability to study mycorrhizae spores, unlocking new insights into their ecological roles and agricultural applications.

Ketoconazole's Effectiveness: Can It Eliminate Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Ecological impact of spore dimensions

Mycorrhizal spores, typically ranging from 20 to 100 micrometers in diameter, play a pivotal role in soil ecosystems. Their size is not arbitrary; it directly influences their dispersal, survival, and colonization efficiency. Smaller spores, such as those of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), are more easily transported by wind and water, increasing their reach across diverse habitats. Larger spores, like those of ectomycorrhizal fungi, often rely on animal vectors or root exudates for dispersal, limiting their range but enhancing their ability to penetrate soil matrices. This size-driven dispersal mechanism ensures that mycorrhizal fungi can colonize a variety of ecosystems, from arid deserts to dense forests, fostering plant health and soil stability.

The ecological impact of spore dimensions extends to their interaction with soil particles and microbial communities. Smaller spores can navigate through finer soil pores, increasing their chances of encountering host plant roots. For instance, AMF spores, averaging 40–60 micrometers, are adept at colonizing crops like wheat and maize, improving nutrient uptake and drought resistance. Larger spores, such as those of the genus *Pisolithus* (50–100 micrometers), are better suited for coarser soils and woody plants, forming robust symbiotic relationships with trees like pines and oaks. This size-specific adaptation ensures that mycorrhizal fungi can thrive in diverse soil textures, enhancing ecosystem resilience.

Spore size also influences their survival in adverse conditions. Larger spores often contain more lipid reserves, enabling them to withstand desiccation and nutrient scarcity. For example, ectomycorrhizal spores can remain dormant in soil for years, waiting for favorable conditions to germinate. Smaller spores, while more vulnerable to environmental stressors, compensate with higher production rates, ensuring population persistence. This trade-off between size and survival strategy highlights the evolutionary precision of mycorrhizal fungi, allowing them to dominate soil ecosystems globally.

Practical applications of understanding spore dimensions are evident in agriculture and restoration ecology. Farmers can select mycorrhizal inoculants based on spore size to match soil type and crop needs. For sandy soils, smaller AMF spores are ideal, while clay-rich soils benefit from larger ectomycorrhizal spores. In reforestation projects, using spore size as a criterion ensures that introduced fungi can effectively colonize tree roots, accelerating ecosystem recovery. For instance, applying *Rhizophagus irregularis* (spore size: 30–50 micrometers) to degraded lands can enhance phosphorus uptake in young trees, promoting growth.

In conclusion, the dimensions of mycorrhizal spores are a critical determinant of their ecological role. From dispersal and soil penetration to survival and application in agriculture, spore size shapes the dynamics of plant-fungal interactions. By leveraging this knowledge, ecologists and farmers can optimize mycorrhizal contributions to ecosystem health and productivity. Understanding spore dimensions is not just an academic exercise—it’s a practical tool for fostering sustainable landscapes.

Do Dried Spores Die? Unraveling the Survival Mystery of Spores

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Species-specific spore size ranges

Mycorrhizal spores, the reproductive units of symbiotic fungi, exhibit species-specific size ranges that are critical for their ecological roles and identification. For instance, *Glomus intraradices*, a common arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, produces spores ranging from 80 to 200 micrometers in diameter. In contrast, *Pisolithus arhizus*, an ectomycorrhizal species, forms significantly larger spores, often exceeding 1 millimeter. These size variations are not arbitrary; they reflect adaptations to dispersal mechanisms, soil environments, and host plant interactions. Understanding these ranges is essential for researchers and practitioners in ecology, agriculture, and forestry, as spore size influences germination rates, colonization efficiency, and fungal community dynamics.

Analyzing spore size data reveals patterns that correlate with mycorrhizal types. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) typically produce smaller spores, averaging 50 to 300 micrometers, which are well-suited for soil penetration and root colonization. Ectomycorrhizal fungi (ECM), on the other hand, often generate larger spores, ranging from 500 micrometers to several millimeters, facilitating above-ground dispersal via wind or animals. These differences highlight evolutionary strategies: AMF prioritize soil-based persistence, while ECM fungi invest in long-distance dispersal to reach new hosts. Such distinctions are vital for selecting appropriate fungal species in restoration projects or agricultural inoculants.

For practical applications, knowing species-specific spore size ranges aids in laboratory and field techniques. When isolating spores from soil samples, sieving methods must be tailored to target sizes—for example, using 30–50 micrometer meshes for AMF spores and larger meshes for ECM spores. In inoculant production, spore size influences dosage rates; smaller AMF spores may require higher concentrations (e.g., 10^6 spores per gram of soil) compared to larger ECM spores (e.g., 10^4 spores per gram). This precision ensures effective fungal establishment and maximizes benefits for plant growth and nutrient uptake.

A comparative study of spore sizes across mycorrhizal species also sheds light on their ecological niches. For example, *Amanita muscaria*, an ECM fungus, produces spores around 10 micrometers in length, optimized for wind dispersal in forest ecosystems. Conversely, *Rhizophagus irregularis*, an AMF, forms spores up to 250 micrometers, suited for persistence in disturbed soils. These adaptations underscore the importance of spore size in fungal survival strategies. By studying these ranges, scientists can predict how different mycorrhizal species respond to environmental changes, such as climate shifts or land-use alterations.

In conclusion, species-specific spore size ranges are a cornerstone of mycorrhizal biology, offering insights into fungal ecology and practical applications. From laboratory techniques to field interventions, understanding these ranges enables more effective use of mycorrhizal fungi in agriculture, restoration, and research. Whether isolating spores, formulating inoculants, or studying fungal communities, this knowledge ensures precision and success in harnessing the power of these symbiotic organisms.

Do All Cells Produce Spores? Unraveling the Truth Behind Cellular Reproduction

You may want to see also

Role of spore size in dispersal

Mycorrhizal spores, typically ranging from 10 to 100 micrometers in diameter, exhibit a size diversity that directly influences their dispersal mechanisms. Smaller spores, such as those of *Glomus* species (20–40 μm), are more easily carried by wind, enhancing their ability to colonize distant habitats. Larger spores, like those of *Pisolithus arhizus* (up to 100 μm), rely more on animal vectors or water for dispersal due to their reduced aerodynamic efficiency. This size variation is not arbitrary but a strategic adaptation to environmental conditions, ensuring species survival across diverse ecosystems.

Consider the role of spore size in wind dispersal, a critical factor for mycorrhizae in open environments. Spores below 50 μm are optimal for wind transport, as they remain suspended longer in air currents. For instance, *Rhizophagus irregularis* spores, averaging 30 μm, are frequently found in agricultural soils far from their origin, demonstrating their wind-dispersal prowess. In contrast, larger spores require higher wind speeds or additional forces, limiting their range. Land managers can leverage this knowledge by selecting smaller-spored mycorrhizal species for soil inoculation in wind-exposed areas, ensuring broader colonization.

Water dispersal favors intermediate-sized spores, typically 40–70 μm, which balance buoyancy and resistance to degradation. In wetland ecosystems, *Hebeloma* spores (50–60 μm) are commonly transported via surface runoff, colonizing new root systems downstream. However, spores smaller than 40 μm risk rapid sedimentation, while those larger than 70 μm may not remain suspended long enough for effective dispersal. When restoring riparian zones, practitioners should prioritize mycorrhizal species with this size range to maximize spore movement through water channels.

Animal-mediated dispersal, or zoochory, often involves larger spores that adhere to fur, feathers, or digestive tracts. *Amanita* spores, averaging 80–100 μm, are frequently dispersed by rodents and birds, as their size facilitates attachment to animal surfaces. This mechanism is particularly effective in forested areas where animal activity is high. Conservationists can enhance mycorrhizal networks in fragmented habitats by introducing larger-spored species alongside wildlife corridors, ensuring spores are carried between isolated patches.

Understanding spore size is not merely academic—it has practical implications for agriculture, ecology, and restoration. For example, in no-till farming systems, selecting mycorrhizal inoculants with smaller spores can improve soil colonization via wind dispersal, reducing the need for mechanical incorporation. Conversely, in reforestation projects, larger spores may be more effective if animal vectors are abundant. By tailoring spore size to dispersal pathways, practitioners can optimize mycorrhizal establishment, fostering healthier ecosystems and more productive crops.

Buying Spores in Massachusetts: Legalities, Sources, and Cultivation Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A typical mycorrhizal spore ranges in size from 10 to 100 micrometers (μm) in diameter, depending on the fungal species.

No, mycorrhizal spore size varies widely among different fungal species, with some being as small as 10 μm and others exceeding 100 μm.

No, mycorrhizal spores are microscopic and cannot be seen with the naked eye; a microscope is required to observe them.

Spore size can influence factors like dispersal, germination, and colonization efficiency, but it does not directly determine the overall function of mycorrhizae.

Mycorrhizal spores are generally larger than many other fungal spores, such as those of molds or rust fungi, which are often smaller than 10 μm.