The question of whether all cells produce spores is a fascinating one, delving into the diverse reproductive strategies of living organisms. Spores are specialized cells produced by certain organisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and plants, as a means of reproduction, dispersal, and survival in harsh conditions. However, not all cells have the ability to produce spores. This capability is largely dependent on the organism's evolutionary lineage and ecological niche. For instance, while many fungi and bacteria rely on spore formation for propagation and endurance, animal and most plant cells do not produce spores, instead utilizing other methods like mitosis, meiosis, or seed production for reproduction and survival. Understanding which cells produce spores and why provides valuable insights into the adaptability and diversity of life on Earth.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do all cells produce spores? | No, not all cells produce spores. |

| Types of cells that produce spores | Primarily prokaryotic cells (bacteria) and some eukaryotic cells (fungi, plants, and a few protists). |

| Purpose of spore production | Survival in harsh conditions (e.g., heat, cold, desiccation, lack of nutrients). |

| Examples of spore-producing organisms | Bacteria (endospores), fungi (conidia, zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores), plants (pollen, seeds), and some protists (e.g., algae). |

| Characteristics of spores | Highly resistant, dormant, and metabolically inactive; can remain viable for extended periods. |

| Cells that do not produce spores | Animal cells, most plant cells (except reproductive structures like pollen and seeds), and many protists. |

| Mechanism of spore formation | Involves specialized cellular processes like endospore formation in bacteria or meiosis in fungi and plants. |

| Environmental triggers for spore production | Nutrient depletion, temperature extremes, pH changes, and other stressful conditions. |

| Role in reproduction | Spores can serve as reproductive units in fungi and plants, ensuring dispersal and survival of the species. |

| Comparison with vegetative cells | Spores are more resilient than vegetative cells, which are actively growing and metabolizing. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation in Bacteria: Certain bacteria form endospores for survival in harsh conditions, not all bacterial cells do this

- Fungal Spores: Fungi like molds and yeasts produce spores, but not all fungal cells are spore-forming

- Plant Spores: Plants like ferns and mosses produce spores, but not all plant cells are involved

- Animal Cells: Animal cells do not produce spores; reproduction is through mitosis or meiosis only

- Protist Spores: Some protists form spores, but not all protist species or cells have this ability

Sporulation in Bacteria: Certain bacteria form endospores for survival in harsh conditions, not all bacterial cells do this

Not all cells produce spores, and this distinction is particularly evident when examining the microbial world. While some organisms, like fungi and certain plants, rely on spore formation for reproduction and dispersal, the process is not universal. In the bacterial domain, sporulation is a specialized survival strategy employed by a select group of species. This mechanism, known as endospore formation, is a remarkable adaptation that allows bacteria to endure extreme environmental conditions.

The Art of Bacterial Sporulation:

Imagine a bacterial cell transforming into a highly resistant, dormant structure, capable of withstanding the harshest of environments. This is the essence of sporulation in bacteria. When faced with adverse conditions such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or desiccation, certain bacterial species initiate a complex developmental process. The cell divides asymmetrically, forming a smaller cell, the forespore, within the larger mother cell. Through a series of intricate morphological and biochemical changes, the forespore matures into an endospore, a structure with an incredibly resilient coat and a condensed, dehydrated core.

A Survival Strategy:

Endospores are not a means of reproduction but rather a survival tactic. They are metabolically inactive, with their DNA protected by multiple layers, including a thick spore coat and a cortex rich in peptidoglycan. This dormant state enables endospores to endure conditions that would be lethal to the vegetative bacterial cell. For instance, *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species can form endospores that survive boiling temperatures, radiation, and prolonged desiccation. These spores can remain viable for years, even decades, until they encounter favorable conditions for germination and return to their active, reproductive state.

Selective Sporulation:

It is crucial to emphasize that sporulation is not a universal bacterial trait. Only a limited number of bacterial genera, primarily within the Firmicutes phylum, have the genetic capacity for endospore formation. This process is highly regulated and energy-intensive, requiring specific environmental cues and a series of intricate cellular events. The ability to form endospores provides these bacteria with a competitive advantage in unpredictable and harsh ecosystems, ensuring their long-term survival.

Practical Implications:

Understanding bacterial sporulation has significant implications in various fields. In medicine, recognizing the sporulation capacity of pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* is essential for effective disinfection and sterilization protocols. In the food industry, controlling spore-forming bacteria is critical for food safety and preservation. Moreover, studying sporulation mechanisms can inspire the development of preservation techniques for heat-sensitive materials and even inform astrobiology, as endospores' resilience raises questions about the potential for microbial life in extreme extraterrestrial environments.

In summary, while not all cells produce spores, certain bacteria have evolved the remarkable ability to form endospores, a strategy that ensures their survival in the face of adversity. This process is a testament to the diversity and adaptability of microbial life, offering valuable insights for both scientific research and practical applications.

Can Cyndaquil Learn Spore? Exploring Moveset Possibilities in Pokémon

You may want to see also

Fungal Spores: Fungi like molds and yeasts produce spores, but not all fungal cells are spore-forming

Fungi, a diverse kingdom of organisms, have evolved sophisticated mechanisms for survival and propagation, with spore production being a hallmark of many species. Molds and yeasts, for instance, are well-known for their ability to generate spores, which serve as resilient, dormant structures capable of withstanding harsh environmental conditions. These spores can remain viable for extended periods, only germinating when conditions become favorable, such as the presence of moisture and nutrients. This adaptive strategy ensures the longevity and dispersal of fungal species across various ecosystems.

However, it is crucial to understand that not all fungal cells are involved in spore formation. Fungal colonies consist of a network of thread-like structures called hyphae, which are responsible for nutrient absorption and growth. Within these hyphae, only specific cells, often located at the tips or in specialized structures like sporangia, differentiate into spores. This differentiation is a highly regulated process, influenced by factors such as nutrient availability, pH, and temperature. For example, in the mold *Aspergillus*, spore formation occurs in structures called conidiophores, where chains of spores (conidia) develop and are eventually released into the environment.

The process of spore formation in fungi is not only a survival mechanism but also a key factor in their ecological impact. Fungal spores are ubiquitous in the environment, and their ability to disperse over long distances contributes to the spread of fungi in various habitats. This is particularly relevant in agriculture, where fungal spores can cause diseases in crops, and in indoor environments, where mold spores can affect air quality and human health. Understanding which fungal cells produce spores and under what conditions is essential for developing strategies to control fungal growth and mitigate their negative effects.

From a practical standpoint, controlling fungal spore production is a critical aspect of managing fungal infections and contamination. In medical settings, antifungal treatments often target the spore-forming cells or the conditions that trigger spore production. For instance, maintaining low humidity levels can inhibit mold growth and spore formation in indoor spaces. In agriculture, fungicides are applied to crops to prevent spore germination and the subsequent development of fungal diseases. Additionally, understanding the spore-forming capabilities of different fungal species can guide the selection of appropriate control measures, ensuring targeted and effective interventions.

In conclusion, while spore production is a defining feature of many fungi, it is a specialized process limited to specific cells within the fungal colony. This distinction highlights the complexity of fungal biology and the importance of targeted approaches in managing fungal growth. By focusing on the conditions and cellular mechanisms that drive spore formation, researchers and practitioners can develop more effective strategies to control fungi in various contexts, from healthcare to agriculture and environmental management. This nuanced understanding of fungal spores underscores their role not only as agents of survival but also as key targets for intervention.

Do Spore Mines Charge on the Turn They Drop? Explained

You may want to see also

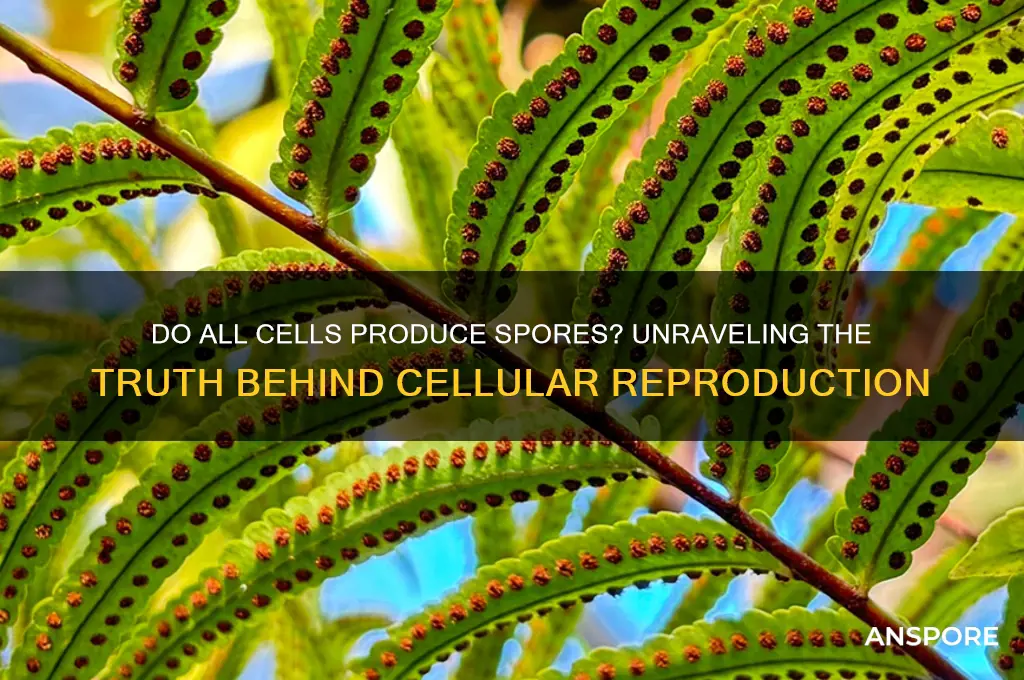

Plant Spores: Plants like ferns and mosses produce spores, but not all plant cells are involved

Not all plants rely on seeds for reproduction; some, like ferns and mosses, harness the power of spores. These microscopic, single-celled structures are produced by specialized cells within the plant, not by every cell. This reproductive strategy, known as alternation of generations, involves a diploid sporophyte generation (the plant we typically see) producing spores through meiosis. These spores then develop into a haploid gametophyte generation, which produces gametes for sexual reproduction.

Understanding this process is crucial for gardeners and botanists alike. For instance, propagating ferns from spores requires specific conditions: a humid environment, a sterile growing medium, and careful temperature control.

The production of spores is a highly specialized process, confined to specific structures within the plant. In ferns, these structures are called sporangia, typically found on the undersides of fronds. Mosses, on the other hand, produce spores in capsules located at the tips of their gametophytes. This localization highlights the fact that spore production is not a universal function of plant cells, but rather a task delegated to specialized tissues.

This specialization allows plants to allocate resources efficiently, focusing energy on growth, photosynthesis, and other essential functions in non-reproductive cells.

While ferns and mosses are prime examples of spore-producing plants, they are not alone. Other plant groups, such as horsetails and clubmosses, also utilize this reproductive strategy. However, it's important to note that spore production is primarily associated with non-seed plants, also known as pteridophytes and bryophytes. Seed plants, including flowering plants and conifers, have evolved a different reproductive mechanism involving seeds, which offer greater protection and nutrient storage for the developing embryo.

The study of plant spores offers valuable insights into plant evolution and diversity. By examining spore morphology and distribution, scientists can trace the evolutionary history of different plant groups and understand their adaptations to various environments. Furthermore, the ability to cultivate plants from spores provides a powerful tool for conservation efforts, allowing for the propagation of rare and endangered species.

Can Archaea Organisms Reproduce via Spores? Unveiling Their Unique Reproduction Methods

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.49 $14.69

Animal Cells: Animal cells do not produce spores; reproduction is through mitosis or meiosis only

Animal cells, unlike their fungal and bacterial counterparts, do not produce spores as a means of reproduction or survival. This fundamental distinction highlights the unique reproductive strategies of animal cells, which rely exclusively on mitosis and meiosis. Mitosis allows for growth, repair, and asexual reproduction by producing genetically identical daughter cells, while meiosis ensures genetic diversity through sexual reproduction, generating gametes with half the number of chromosomes. These processes are finely tuned to support the complex multicellular structures of animals, from humans to insects.

Consider the practical implications of this limitation. For instance, animals cannot survive harsh environmental conditions by forming dormant spores, as some bacteria and fungi do. Instead, they must adapt through behavioral changes, migration, or physiological mechanisms like hibernation. This vulnerability underscores the importance of stable environments for animal survival and explains why animals are more susceptible to extinction during rapid environmental shifts. Understanding this difference is crucial for fields like conservation biology, where strategies must account for the reproductive constraints of animal cells.

From an evolutionary perspective, the absence of spore production in animal cells reflects their specialization for multicellularity. Spores are often associated with unicellular or simple multicellular organisms that require rapid dispersal and survival in adverse conditions. Animals, however, have evolved intricate tissues, organs, and systems that demand precise cellular coordination. Mitosis and meiosis ensure that this complexity is maintained and passed on accurately, albeit at the cost of spore-like resilience. This trade-off illustrates the balance between adaptability and specialization in the animal kingdom.

For educators and students, emphasizing this distinction can clarify the diversity of life’s reproductive strategies. A hands-on activity, such as comparing cell division in animal and fungal cultures, can illustrate these differences vividly. For example, observing yeast cells (which can reproduce both sexually and asexually, including through spores) alongside animal cells under a microscope provides a tangible contrast. This approach not only reinforces biological concepts but also fosters an appreciation for the ingenuity of life’s solutions to survival and reproduction.

In practical terms, the inability of animal cells to produce spores has significant implications for medical research and biotechnology. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which can be challenging to eradicate due to their dormant resilience, animal cells are more susceptible to targeted therapies. However, this also means that preserving animal tissues, such as in organ transplantation or cell culture, requires controlled environments to prevent cell death. Researchers must account for these limitations when developing treatments or storing biological materials, ensuring that conditions mimic the stable environments animal cells depend on.

Are Psilocybin Spores Legal? Understanding the Current Laws and Regulations

You may want to see also

Protist Spores: Some protists form spores, but not all protist species or cells have this ability

Not all cells produce spores, and this is particularly evident when examining the diverse world of protists. Protists are a polyphyletic group of eukaryotic organisms, often unicellular, that do not fit neatly into the categories of plants, animals, or fungi. Among these, only specific species have evolved the ability to form spores as a survival mechanism. For instance, certain algae, such as *Chlamydomonas*, can produce dormant zygospores under unfavorable conditions, while others, like *Amoeba*, lack this capability entirely. This variability highlights the importance of understanding that spore formation is not a universal trait, even within closely related organisms.

Analyzing the conditions under which protists form spores reveals a strategic adaptation to environmental stress. Spores serve as a protective shell, allowing cells to withstand harsh conditions such as desiccation, extreme temperatures, or nutrient scarcity. For example, *Plasmodium*, the protist responsible for malaria, forms oocysts in the mosquito vector, ensuring its survival during transmission. However, not all protists face the same environmental pressures, and those thriving in stable habitats, like freshwater *Paramecium*, have no need for such mechanisms. This underscores the principle that spore formation is an evolved response to specific ecological challenges, not a default cellular function.

From a practical standpoint, understanding which protists produce spores is crucial for fields like microbiology and environmental science. For instance, in water treatment, knowing that certain spore-forming algae can survive chlorination helps in developing more effective disinfection methods. Conversely, in agriculture, recognizing that non-spore-forming protists may be more susceptible to environmental changes can guide pest management strategies. This knowledge also aids in predicting how protists might respond to climate change, as spore-forming species may have a survival advantage in fluctuating conditions.

Comparatively, the ability to form spores distinguishes protists from other microorganisms, such as bacteria, which produce endospores, and fungi, which generate a variety of spore types. While bacterial endospores are more resilient, protist spores often serve a similar purpose but with species-specific variations. For example, fungal spores are typically involved in reproduction and dispersal, whereas protist spores are primarily for survival. This comparison emphasizes the unique evolutionary pathways that have shaped spore formation across different domains of life, further illustrating why not all cells produce spores.

In conclusion, the formation of spores among protists is a specialized trait, not a universal one. By examining specific examples, ecological contexts, and practical applications, it becomes clear that spore production is a strategic adaptation to environmental stress rather than a default cellular process. This understanding not only enriches our knowledge of protist biology but also has tangible implications for fields ranging from water treatment to climate science. Recognizing this variability is essential for anyone studying or working with these diverse organisms.

Are All Spore-Forming Bacteria Gram-Positive? Unraveling the Myth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all cells produce spores. Only certain types of organisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and some plants, have the ability to produce spores as a means of reproduction or survival.

Cells from spore-forming organisms like bacteria (e.g., Bacillus and Clostridium), fungi (e.g., molds and mushrooms), and some plants (e.g., ferns and mosses) are known to produce spores.

No, animal cells do not produce spores. Spores are a characteristic of certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, not animals.

Cells produce spores as a survival mechanism to withstand harsh environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, lack of nutrients, or desiccation. Spores can remain dormant for long periods until conditions improve.

No, human cells do not produce spores. Spores are not a feature of human biology or any animal cells.